Last week I discussed Down The Gasoline Trail (1936) and briefly mentioned the animated sequence in 1941’s Drawing Account. It’s time to look at the program that these two films, along with the cult classics A Case Of Spring Fever (1941) and the Nicky Nome Technicolor cartoons, were produced for: The ‘Direct Mass Selling’ short subject program produced by the Jam Handy Organization for the Chevrolet Division of General Motors Corporation, that was in use from 1935 to early 1942.

An ad showcasing the Jam Handy Organization cinematic approach to industrial film productions for sponsored film productions shown in theaters.

‘Direct Mass Selling’ was launched in March of 1935 by Jam Handy and Chevrolet for Chevrolet Dealers to attract interest in their products through the use of short films for public exhibition. The program was meant to overhaul and update the successful ‘Quality Dealer Program’ Jam Handy had produced for Chevrolet in the late 1920s through 1934, and is credited by some historians for saving Chevrolet. This precursor consisted of some theatrical films but mainly live performance acts and stunts created by Jam Handy to market Chevrolet sedans around the country. (It should be briefly noted that in addition to film production, Jam Handy also produced acts and playlets for the stage and live exhibitions.)

The few films that were made for the program were mixed media presentations that utilized live action demonstrations and technical animation sequences drawn by Rockwell Barnes, but were apparently very heavy in advertising nature. This is demonstrated in one of the only available (and possibly surviving) ‘Quality Dealer Program’ films, “Facts On Friction” from 1934:

‘Direct Mass Selling’ eliminated the live exhibition acts and instead focused on the production of one reel short films along with a few two-reelers. While the films would be advertising films, they took an extremely different and clever approach to market their material than those produced for the ‘Quality Dealer Program’. Instead of bombarding viewers with Chevrolet’s accomplishments, advertising of the cars was quiet and only done by product/brand placement and narration/acting hinting at Chevrolet’s superiority, without even mentioning the name of Chevrolet.

The reason for this was to make the films appear as normal entertainment, novelty educational films that viewers would want to see as a short at a movie theatre or as a novelty at a community club meeting, school assembly etc.. As films very obvious in advertising nature were (and still are) not the most popular films to view, many viewers would leave during their exhibition to take their cigarette break, bathroom break, etc. thus limiting the films’ audience. ‘Direct Mass Selling’ set out to address this and attempted to capture the interest of all viewers by subliminally showcasing what made Chevrolet the most unique car on the low price market, by relating them to common interest topics. Topics consisting of:

• how specific parts of an automobile worked and contributed to it’s operation and safety,

• safe driving techniques,

• how an automobile contributes to our everyday lives or even saves the day,

• topics not related to automobiles in any manner but could be tied to the Chevrolet brand,

• how automobile manufacturing contributes to the American lifestyle,

were all put to use to emphasize that Chevrolet was the safest, comfortable, best ventilated, scientifically engineered car on the market. Frequently the films highlighted Chevrolet’s “Knee Action” (i.e. how springs in the wheels reduce the bumpiness of a ride), air ventilation to bring comfort for those traveling, and streamline design allowing the vehicle to get the best economy.

The one-reel ‘Direct Mass Selling’ entries utilized a variety of formats that were frequently put to use for traditional Hollywood short subjects:

• Documentary shorts – One shot common interest educational films that were similar in nature to M-G-M’s popular “Pete Smith Specialty” series.

• Narrative shorts – One shot films that dealt with common interest topics, only in narrative form. Subjects ranged from comedies dealing with safe driving to action dramas with a Chevrolet saving the day.

• Novelty Newsreels – Two different series, “The Chevrolet Leader News” and “Chevrolet Laughs and Flashes”, that highlighted bizarre antics, tricks and uses of automobiles. The content of these films puts to use some of Jam Handy’s many acts performed for the ‘Quality Dealer Program’ shows. In many cases these films are the only existing footage and records of these acts. It should be noted that these films were not newsreels like the “Paramount News”, “Fox Movietone News”, “MGM Hearst Metrotone News”, etc. newsreel series which were issued several times per week (causing over 100 issues per year!) to keep patrons up to date with current events. Instead Jam Handy’s Chevrolet ‘newsreels’ were novelty films only issued four to six times a year and rarely (if ever) took the place of an actual newsreel. In many ways they were very similar from both a content and production schedule wise to Jerry Fairbanks’ “Popular Science” series for Paramount, which is what they should be categorized with.

• Novelty Newsreels – Two different series, “The Chevrolet Leader News” and “Chevrolet Laughs and Flashes”, that highlighted bizarre antics, tricks and uses of automobiles. The content of these films puts to use some of Jam Handy’s many acts performed for the ‘Quality Dealer Program’ shows. In many cases these films are the only existing footage and records of these acts. It should be noted that these films were not newsreels like the “Paramount News”, “Fox Movietone News”, “MGM Hearst Metrotone News”, etc. newsreel series which were issued several times per week (causing over 100 issues per year!) to keep patrons up to date with current events. Instead Jam Handy’s Chevrolet ‘newsreels’ were novelty films only issued four to six times a year and rarely (if ever) took the place of an actual newsreel. In many ways they were very similar from both a content and production schedule wise to Jerry Fairbanks’ “Popular Science” series for Paramount, which is what they should be categorized with.

• Technicolor Cartoons – Originally several one shot cartoons that eventually evolved into the notorious “Nicky Nome” series. As the animated cartoon medium, especially those in color, had become extremely popular with audiences (thanks to the efforts of Walt Disney) Jam Handy recognized the potential of using Technicolor cartoons for ‘Direct Mass Selling’. The first Technicolor cartoon A Coach For Cinderella (1936/7) tailgated (no pun intended) off of the popular musical “Silly Symphony” format to demonstrate the manufacturing assembly line process. The following cartoons attempted to build off of Coach’s main character, Nicky Nome and his Grasshopper Horace, and masquerade them as Chevrolet’s ‘Mickey Mouse’ and ‘Pluto’. While the Nicky Nome cartoons are not the greatest in storytelling they are memorable for their slick animation by Jim Tyer and vibrant music scores by JHO musical director Samuel Benavie. (These Technicolor cartoons will be discussed in more detail in a future article.)

In addition to one-reelers a small number of documentary two-reelers, advertised as ‘institutionals”, that highlighted (Chevrolet) American manufacturing were also produced. Interestingly the program never adapted a series of travelogues, however this may have been because Handy’s/Chevrolet’s interest in film content was using common interest topics to showcase what made Chevrolet cars unique. A travelogue that highlighted popular sights around the country may have been too evident in advertising nature and thus boring to audiences.

A non-theatrical exhibition at a Community club meeting of 1935’s “Spring Harmony”.

The one-reel films were released on a scheduled basis and intended exhibition was for theatrical showings at movie theaters, and non-theatrical screenings at Rotary Club meetings, School auditoriums/gymnasiums, factory cafeterias, etc. and even outdoor screenings at a park or fair. The two-reel ‘institutionals’ while distributed theatrically in some communities, were created mainly for non-theatrical distribution at schools and club meetings. While the films shown at the theatre played as a selected short subject to accompany a feature attraction, they were the main attraction of non-theatrical screenings. Distribution of the films was handled in a variety of different methods for both theatrical and non-theatrical exhibitions.

For theatrical distribution, the films were distributed in two different manners. The first method was a Chevrolet dealer would pay a local theatre to exhibit the latest release as a selected short subject in a film program, and the film would be distributed directly to the theatre by the Jam Handy Organization. The second method was having a film distributor distribute the films directly to interested cinemas without having to go through a Chevrolet dealer. At first, this method was handled by the Jam Handy Organization, however as the shorts (such as several of the safe driving comedies and common interest documentaries) picked up more positive reception they caught the attention of mainstream distributors.From mid-1935 through part of 1937 the films were handled by Audio-Cinema Inc., a division of AT&T (who also ran Western Electric and Audio Productions) and distributed through the states rights system, to various distributors in different regions. In 1937 when AT&T disbanded Audio-Cinema, Western Electric, etc. to avoid an anti-trust suit from the FCC, Monogram Pictures took an interest in the films and distributed them to theaters from 1937 to the program’s cancellation in 1942. Monogram, the bottom of all of the major studios, frequently distributed short subjects from other production companies such as re-issues of Hal Roach’s comedies and various films from Cartoon Films Ltd. In addition to the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ shorts, they also handled distribution for some of Jam Handy’s other productions from 1937 up until the early 1950s (such as the 1947 Rudolf the Red Nosed Reindeer cartoon).

Theatrical distribution of the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ films as handled by distributors (without the involvement of Chevrolet). The Jam Handy Organization in early 1935. Audio-Cinema from mid-1935 to 1937. Monogram Pictures from 1937 to 1942.

Perhaps the best manner to get further acquainted with ‘Direct Mass Selling’ is with the Jam Handy Organization itself. Here is a 1937 film entitled “Helping You Sell” that was meant only for the eyes of Chevrolet dealers which discusses the ambitions of the program and how dealers could use the films to attract customers for their product. The film features clips, both live action and animated, from several different ‘Direct Mass Selling’ films

Many of the films highlighted in “Helping You Sell” were individual documentary films, and for good reason. While the majority of the narrative shorts, the Technicolor cartoons, and the novelty newsreels were good, it was really the documentary films that were the crown jewel of the program; several of which were in a class of their own. One unique quality about several of the documentaries (a handful of which will be showcased a few paragraphs down and next week) was how they were able to take the most boring and simple ideas related to an automobile (i.e. turning a car, the springs on a car, the gas line, etc.) and present them in a manner that was not only educational but entertaining. This was accomplished through several different showmanship techniques and mixed media sequences consisting of but not limited to car demonstrations and stunts, circus type acts, cartoon sequences, and most notably Rockwell Barnes’ technical animation sequences.

Several of these techniques are demonstrated in the very first ‘Direct Mass Selling’ release “Spring Harmony”, a documentary that was completed and released in early March of 1935 (and interestingly was not registered for copyright) and discusses how springs contribute to a Chevrolet’s harmonious travel along roads, both old and new. After getting past the rather peculiar, almost nauseating opening credits viewers are treated to a decent presentation consisting of live action demonstrations and technical animation sequences regarding the evolution and development of automobile springs. While the majority of advertising is kept to a minimum and strictly to visuals, the narrator Lowell Thomas does briefly mention Chevrolet’s name once at the film’s end. However this was rather rare as future installments don’t do this.

With the exception of the musical notes in the opening credits, the vast majority of “Spring Harmony” was probably enjoyed by audiences who saw it in the 1930s, thus leading the way for additional entries. One observation to note is Barnes’ technical animation sequences were not as elaborate in this first film as they would be in the films to follow, possibly due to the budget that was available to work with. As the “Direct Mass Selling” films impressed Chevrolet and/or picked up in popularity for their entertainment and educational value, more money was evidently made available to the productions. One excellent example of this is 1935’s “No Ghosts”.

Released in mid-Summer of 1935 (registered for copyright on March 23 and completed July 15) only a few months following “Spring Harmony”, the higher production values are present and overall are far more ambitious. Viewers are treated to an elaborate mixed media presentation that not only features a better written script, but higher detailed technical animation, better shot footage, very clever photography effects, cartoon sequences, etc., to educate how a perfectly manufactured Y-K steel frame prevents cars from becoming “haunted”. All of this adds up to a memorable film that without question outdoes “Spring Harmony”. (Note the bizarre fun animation by Barnes of the “Haunted car” at 2:32)

As more ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries were produced, the production values, story telling and showmanship techniques continued to increase as well. This is perfectly demonstrated in this article’s final two examples: 1938’s “Color Harmony” and 1937’s “On The Air”, both of which are personal favorites of the author.

“Color Harmony” was completed on November 4th of 1938 and was apparently not registered for copyright; This is odd as the film itself is a documentary that Jam Handy was extremely proud of and probably could have given Pete Smith a run for his money had it not been an advertisement film. The theme of the film has absolutely nothing to do with automobiles but instead showcases the fascinating and complex world of how the human eye sees and interprets color. Once again viewers are treated to a stellar mixed media presentation that features “photography faithful” and “visualize the invisible” technical animation by Rockwell Barnes which demonstrates the mysterious workings of the eye’s nerves and visual cells.

A trade ad for 1938’s “Color Harmony”, a film that the Jam Handy Organization was very proud of and credits as being the “first and only picture in the world using color to explain color”. The film itself is a masterpiece which beautifully demonstrates the talents of Rockwell Barnes.

One notable characteristic of the film is how it makes clever use of the black & white to Technicolor technique: The film’s first half that discusses the eye’s basic principals is in black & white, while the second half is appropriately in three-strip Technicolor to discuss how the eye sees color. The grand finale of the production is an animated sequence by Barnes of several different colored Chevrolet automobiles peacefully driving on a road. This sequence indicates that the film was made to generate curiosity in the variety of colors Chevrolet’s were offered in. Note the fun special effects sequence at 2:55 which combines technical animation with a live action dancing toy.

Rockwell Barnes was certainly not the only individual who worked on “Color Harmony” or many other ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries as the Jam Handy Organization employed many talented individuals. Aside from Barnes and Jamison Handy (who was the executive producer of all the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ films) it’s difficult to know for sure who else was involved, however from looking through trade magazines we can kind of guessed who may have.

Francis Lyle Goldman (who I wrote about for Cartoon Research in 2016) certainly worked on many of the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ films, including “Color Harmony”, by contributing various visual effects sequences and stop motion animation. Samuel Benavie, the musical director of the Jam Handy Organization and one of the great overlooked film composers of the era was responsible for all of the studio’s music. Other JHO staff who probably worked on these films consist of former silent movie comedian turned director J. Cullen Landis, and several successful former Hollywood cinematographers such as Gordon Avil and Pierre Mols.

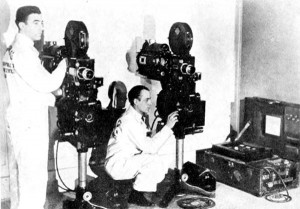

Some of the visionaries behind the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries: Jamison Handy (executive producer and president of JHO), Rockwell Barnes (Director and animator of technical animation and cartoon animation), Frank Goldman (Director of stop motion Animation, visual Effects, some technical animation and cartoon animation), Samuel Benavie (Musical Director and Composer of JHO), J. Cullen Landis (Film Director), Pierre Mols (Cinematographer), Gordon Avil (Cinematographer).

The final example of this article further demonstrates Rockwell Barnes’ animation and Jam Handy’s movie magic in another mixed media DMS documentary “On The Air” (completed on February 22, 1937 and registered for copyright on April 13, 1937). Like “Color Harmony” it deals with a common interest topic not related to automobiles, in this case how radio programs are broadcasted and received by radios.

The film documents how a CBS “Chevrolet Musical Moments” broadcast featuring Rubinoff (a frequent musical guest on the popular Chevrolet program) is recorded in a studio and how it is transmitted to a radio, in this case the radio in a Chevrolet automobile. While the film does not feature any color sequences, it is noteworthy for how it combines Rubinoff’s peaceful recordings of Jimmy Dorsey’s “Green Eyes” and Paul Lincke’s “Spring, Beautiful Spring” to accompany Lowell Thomas’ narration and assists in calmly demonstrating the complex world of radio. Overall it’s a wonderful film and a must see especially for fans of the Golden age of radio!

Next week’s article Direct Mass Selling’s Adventures in Technical Animation, the third and final piece in this trio of Cartoon Research articles, will highlight five more “Direct Mass Selling” documentaries all of which feature amazing technical animation sequences by Rockwell Barnes!

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

That title card is the best A Coach for Cinderella has ever looked.

Just because we are not all commenting doesn’t mean we aren’t reading. The output of Jam Handy is simply staggering in sure quantity. Of course, I am referring to the commercial live action short that may or may not have an animated sequence in it. You look at the 1950s-60s Library of Congress copyright entry books, it seems like one out of every five movies was put out by them, even if hardly any were feature length. General Motors certainly was a bigger distributor and producer than Loews/MGM.

The output was quite massive in the 1930s and 40s as well. In fact it was divided into three separate companies, The Jam Handy Organization, Jam Handy Picture Serviced, and Jam Handy Productions.

Very interesting post. Any idea who animated the “No Ghosts” cartoon sequences?

My guess would be Rockwell Barnes.

Marty Taras, Tom Baron, and Gill Turner were among the animators who had worked at Handy.

Also Bill Nolan, Tom Moore, Bill Strum, Rudy Zamora, and Jim Tyer.

I was wondering where this title card of “A Coach fo Cinderella” comes from. I meen, at the cartoon we see the title over a dark background, without any figures. Is this a reissue? If so, where can we watch the unedited version of the film?