Kricfalusi Explains. In the Los Angeles Times Calendar section for August 9, 1992 about the Ren and Stimpy television series, animator and director John Kricfalusi asked, “Have you been following the press? Some it really bums me out, particularly the Time magazine article. It was ignorant. You’d expect it to be the most intelligent. They made us sound like child molesters, like all we care about is disgusting people. Of course, we do want to disgust people, but that’s not all we do. We go for both the highest common denominator and the lowest. What we do is avoid the middle.

“Too far to me would be disembowelment or something, blood spurting everywhere. The booger jokes are completely harmless. The grosser you can draw a booger, the funnier it is.

“There’s this impression that I only want to do cult animation. That’s people’s fear, and they want to tone me down so I’ll appeal to a more popular audience – which is crazy to me. Because the last thing I want is a cult following. I don’t want ten people watching the show. It’s a popular medium I’m using and my influences are popular.”

Beastly Voice. In the Boston Globe May 15, 1992, Kirk Wise, co-director of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991) stated that when looking for someone to provide the voice for the Beast, “We needed someone who could sound like an eight foot tall hairy monster and at the same time express the warmth, sincerity and intelligence of a human prince. Robby (Benson) was the first person we heard who actually managed to combine both in a believable way.”

Beastly Voice. In the Boston Globe May 15, 1992, Kirk Wise, co-director of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991) stated that when looking for someone to provide the voice for the Beast, “We needed someone who could sound like an eight foot tall hairy monster and at the same time express the warmth, sincerity and intelligence of a human prince. Robby (Benson) was the first person we heard who actually managed to combine both in a believable way.”

The Wisdom of Bakshi. In the Los Angeles Times July 27, 1988, animator and producer Ralph Bakshi said, “I’m an artist and I’m very passionate about the art of animation. That’s the truth. I grew up in a time that if you were reading a comic book, you were a moron. Your mother hit you on the head. What I did (in animation) in the ‘70s were political and social films, very personal statements. Mighty Mouse represents me wanting to entertain people. This isn’t a stance I ‘m taking for commercialism. I’m allowing myself to have more fun. I want to make people fall on the floor laughing.”

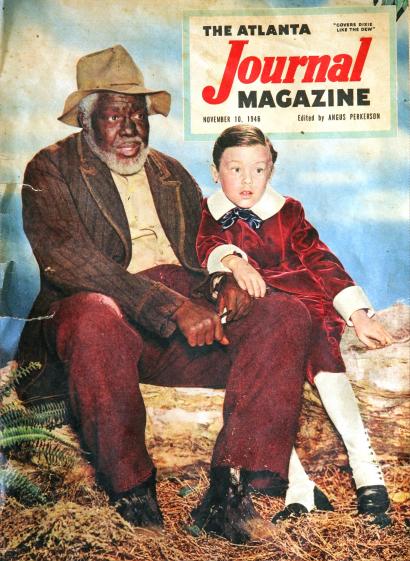

Ruth Warrick on Song of the South. In the Boston Globe newspaper for November 14, 1986, there was an article about the fortieth anniversary of Disney’s Song of the South (1946) screening in Atlanta, Georgia to benefit the restoration of Wren’s Nest, writer Joel Chandler Harris’ home.

UPI writer Bill Lohmann interviewed actress Ruth Warrick, one of the last surviving performers in the movie. “I was absolutely horrified when I came to the first showing (premiere in Atlanta) and found Jim Baskett (who played Uncle Remus) was not there. That just seems so impossible now. The point of the picture is that Uncle Remus was the wise one. He was full of love, joy and humanity. He was the hero. The white folks were kind of stupid and foolish. As far as I’m concerned, this is a very pro-black representation.”

Cartoon Suicide. In 1992, there was controversy over an episode of The Simpsons. “We opened the show with Bart and his class watching a scratchy black-and-white film about zinc,” said creator Matt Groening in an article in the L.A. Daily News February 15, 1992. “It was a send up of those cornball education films we were forced to watch when we were growing up. In the film a young boy imagines a world without zinc so he loses his car, girlfriend and more. Distraught, he puts a gun to his head but nothing happens because there was no zinc in the firing pin.

Cartoon Suicide. In 1992, there was controversy over an episode of The Simpsons. “We opened the show with Bart and his class watching a scratchy black-and-white film about zinc,” said creator Matt Groening in an article in the L.A. Daily News February 15, 1992. “It was a send up of those cornball education films we were forced to watch when we were growing up. In the film a young boy imagines a world without zinc so he loses his car, girlfriend and more. Distraught, he puts a gun to his head but nothing happens because there was no zinc in the firing pin.

“He wakes up thinking ‘Thank God I live in a world of zinc’. I thought it was really funny. Does this encourage teen suicide? If anything, it possibly cheers up suicidal teens by giving them something to laugh at.

“There’s a lot of material in the show that might be beyond kids but my experience has been as a kid and in talking to kids who watch the show is they love not being talked down to. The scene was obviously outrageous. There are so many taboos in television these days, and so many taboos in animation, especially because it’s considered a ‘kiddie’ medium.

“We’ve rejected that label for The Simpsons. It’s a family show in the broadest sense. If anything is going to cause kids to consider suicide, it’s the bad cartoons on Saturday morning.”

Admiring Chuck Jones. In the Orange County Register October 22, 1989, animator and producer Chuck Jones said, “I don’t mind people admiring me if they want to but I don’t think it’s very logical. It’s not like I was St. George knocking off some dumb dragon or anything like that. First of all, you’re talking about something I did a long, long time ago. Secondly, we were doing things that were not expected to last a lifetime. We figured they’d last about three years and then disappear forever. Remember there was no television back then and no place for the cartoons to go after they left the theaters.

Admiring Chuck Jones. In the Orange County Register October 22, 1989, animator and producer Chuck Jones said, “I don’t mind people admiring me if they want to but I don’t think it’s very logical. It’s not like I was St. George knocking off some dumb dragon or anything like that. First of all, you’re talking about something I did a long, long time ago. Secondly, we were doing things that were not expected to last a lifetime. We figured they’d last about three years and then disappear forever. Remember there was no television back then and no place for the cartoons to go after they left the theaters.

“But I’m not trying to demean what we did. I always took the work very seriously and I’m proud to have been associated with the work we did. It’s just that adulation is impractical and makes me uncomfortable. Nobody noticed us back then. Nobody called us geniuses. And we didn’t feel like artists. We were just trying to make people laugh.”

Voices for Bluth. In 2002, animator and producer Don Bluth said, “The voice is the soul of our characters. The actors come with great personal and professional experiences. Once they know who the character is, they bring a whole new dimension to it. When we imagine our character’s personality, we review other films (usually live action movies or TV shows) to find a similar role played by various actors. Sometimes it’s their acting skills, sometimes it’s “type”, sometimes it’s just the sound of their voice. It’s very important to the building of the characters, so we do it carefully.

“In Anastasia (1997), we worked hard at getting some “Meg Ryan” in the Anya character. We actually videotaped a voice recording session of her, for the animators to see her act. We also provided ‘live’ actor’s reference for the animation of the human characters in most of our films. Many times we ask the actors to look at films done by the voice actors and then incorporate some of the voice actor’s traits in their performance.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Of course, segregation was the reason why Baskett wasn’t there, but SONG OF THE SOUTH was actually not the only premiere Disney held in a “whites only” venue during the Jim Crow years. The world premiere of the first “Mickey Mouse” color cartoon THE BAND CONCERT was at Dallas’s Palace Theater in 1935, and the world premiere of 101 DALMATIANS was at the Florida Theater in St. Petersburg, Florida in 1961. So, basically, this activity spanned his whole career in film, and SONG OF THE SOUTH was not a fluke.

The Ruth Warwick anecdote followed by the Christopher P. Lehman comment interest me. I like looking at specific details rather than engaging in a broader “racist or not” debate. I’d like to know more how Disney’s premiering films in whites only theatres compares to other major producers. Were there other major producers who took a moral stand and refused to premiere films in white only theatres?

I’ve noticed a there was a Casper the Friendly Ghost cartoon which was a clip episode that shown earlier Casper episode that came out in the mid 1950s about two writers trying to create a new Casper cartoon. In the opening sequence they were showing three items in cases that started with the words “In Case Of…” the third item in the case had a gun with the words “In Case of Getting Fired” which when a employee was fired they can use the gun to commit suicide. But unfortunately in today’s workplace it takes on a totally different meaning if the employee was fired they could used the gun to shoot up the workplace or as it’s known today as Workplace Violence.

There are a number of suicide gags in Warner Bros. cartoons, such as “An Itch In Time” (1943).

Usually,such a gag would be preceded by the line, “(Well) Now I’ve Seen Everything!”, after which the gun would get fired.

Many of these gags were excised by over-eager censors in the 1980’s and 1990’s–but one that was left in (perhaps because it was only on the soundtrack) was the racetrack announcer in “The Grey-Hounded Hare”.

Then, there’s Avery’s “Little ‘Tinker” (1948), whose thoughts turn to poison until he’s met by Dan Cupid (who has to don a gas mask).

I’m sure the reader(s) can find other examples in the classic cartoons.

I heard that the suicide gags were excised by order of Ted Turner, whose father killed himself.

When I think of all the cartoons I was privileged to have seen, I am so glad that this was so. To me, my generation was spoiled with so many terrific and sometimes twisted cartoons on our television airwaves and even, in some cases, back in theaters either added to the film-going experience or as the last vestiges of the Saturday matinee in local theaters. I wish this were still so. It seems now, due to the micro-management going on today, kids of today are not even interested in the art form the way we were, yet the kind of trouble that the parental groups and industry watchdogs thought they were neatly avoiding by removing all “offending” materials from animation, which became the scapegoat of any problem of the age, was still happening, and those wounds are so deep that these are effecting our politics and social behavior. The wounds were far deeper than whether or not a child saw something in an animated cartoon that drove him or her over the edge. I escaped into cartoons; it was this new world for me, especially when I saw animation on the big screen. I wish we could reach that peak again, the timing, the memorable scores, the overall spectacle…or just the story-telling. I know that times must change, but we shouldn’t lose animation’s past at all, even if some of the artists felt that what they were doing was just a boring day’s work and nothing more significant; I liked it all, right down to some of those “so bad, they’re good” cartoons, and there are times when I really believe that the animators knew they were creating nonsense and wallowed in it. I enjoyed just transcending belief; after all, it is “just a cartoon”, right?