The Felix the Cat Sign. The Felix the Cat animated character was borrowed as an icon by L.A. automobile dealer Winslow Felix who opened Felix Chevrolet in 1921.

Winslow Felix was a friend of Pat Sullivan who produced the Felix the Cat cartoon shorts at the time. In exchange for a new car, Sullivan allowed his close friend to use Felix the Cat in advertising, beginning at the 11th Annual Los Angeles Auto Show in 1923 with an image picturing the animated feline carrying a briefcase with the Chevrolet logo and the words “Order Yours from Felix”.

Winslow also attracted attention of potential buyers by painting the “good luck” feline all over his Chevrolet roadster convertible and driving a giant head of the cat around town in the back seat. He also put the famous cartoon cat on the side of mobile libraries that journeyed through neighborhoods playing music like a Good Humor truck.

Winslow also attracted attention of potential buyers by painting the “good luck” feline all over his Chevrolet roadster convertible and driving a giant head of the cat around town in the back seat. He also put the famous cartoon cat on the side of mobile libraries that journeyed through neighborhoods playing music like a Good Humor truck.

The advertising proved extremely successful, and Felix Chevrolet sales grew steadily as it moved to successively larger locations. In 1934, Gilmore Stadium showcased midget car races Thursday nights, and Felix was there to sponsor the sport on behalf of the car dealership.

The massive famous neon sign appeared for the first time at the new location of the car dealership on Figueroa and Jefferson Boulevard in 1958. The sign was designed by Wayne E. Heath, somewhat based on the revised version of the Felix the Cat character from the 1950s television series. Heath designed signs for Denny’s and Winchell doughnuts. The three-sided sign has Plexiglas-and-neon letters that measure fifteen feet tall.

However, in October 2007, The Los Angeles City Council decided against naming the sign a historical cultural monument despite the recommendation of the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission.

Animated Party Animals. Artist Brice Mack who passed away in 2008 spent most of his early career painting backgrounds for Disney animated feature films including Snow White, Pinocchio, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and more.

Animated Party Animals. Artist Brice Mack who passed away in 2008 spent most of his early career painting backgrounds for Disney animated feature films including Snow White, Pinocchio, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and more.

In 1954, he started his own commercial animation studio, Era Prods., and later Unicorn Prods as well as continuing to consult for Disney until roughly a decade before his death.

He was also known to be as wacky as Ward Kimball when it came to stunts. Mack, along with fellow cartoonists and former Disney artists Dick Shaw and Virgil Partch, once put wheels on a boat and partied on it as they drove it to Las Vegas where a waiting crane lowered it into the pool of the Sands hotel.

Another time, the trio put a train car on a barge and partied as they took it to Catalina Island. In 1961, they held a party on the last Red Car ride from Los Angeles to Long Beach while they and their guests danced to the music of Ward Kimball’s Firehouse Five Plus Two.

Pixar Malcontents. Brad Bird told The McKinsey Quarterly in 2008, “The Incredibles was everything that computer-generated animation had trouble doing. It had human characters. It had hair. It had fire. It had a massive number of sets. The technical team took one look and thought, ‘This will take ten years and cost $500 million. How are we possibly going to do this?’

“So I said, ‘Give us the black sheep. I want artists who are frustrated. I want ones who have another way of doing things that nobody’s listening to. Give us all the guys who are probably headed out the door’. A lot of them were malcontents because they saw different ways of doing things, but there was little opportunity to try them, since the established way was working very, very well.

“So I said, ‘Give us the black sheep. I want artists who are frustrated. I want ones who have another way of doing things that nobody’s listening to. Give us all the guys who are probably headed out the door’. A lot of them were malcontents because they saw different ways of doing things, but there was little opportunity to try them, since the established way was working very, very well.

“We gave the black sheep a chance to prove their theories, and we changed the way a number of things are done here (at Pixar). For less money per minute than was spent on the previous film, Finding Nemo, we did a movie that had three times the number of sets and had everything that was hard to do. All this because the heads of Pixar gave us leave to try crazy ideas.

“One of those ideas was that we didn’t have to make something that would work from every angle. Not all shots are created equal. Certain shots need to be perfect. Others need to be very good. And there are some that only need to be good enough to not break the spell.”

The Hanna-Barbera Philosophy. From the first issue of Exposure Sheet (July 1967), the in-house Hanna-Barbera Studio newsletter, from an article entitled “The Improbable World of Hanna-Barbera” credited to Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera comes this little tid-bit: “If there is an underlying philosophy about our cartoons, it is to project warmth and good feeling. We spoof lots of things—Hollywood, cars, television and even our own animated commercials. However, we don’t see anything funny in violence or sin. Even our villains are nice guys.

“Last week one of our writers created a particularly mean villain. This bad guy was so terrible—a mean-looking, fat, grumpy, old bulldog with a big black, waxed moustache—that we called the writer in to ask him where he had gotten the idea.

“Last week one of our writers created a particularly mean villain. This bad guy was so terrible—a mean-looking, fat, grumpy, old bulldog with a big black, waxed moustache—that we called the writer in to ask him where he had gotten the idea.

“He admitted he once had a teacher in grade school whose appearance and nature fitted a bulldog. We often wonder where the thin line between real and unreal is drawn and by whom.

“We have never attempted to educate youngsters nor preach to them. We have just tried to entertain.”

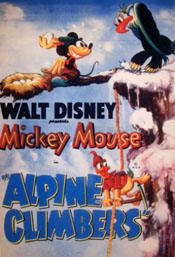

Too Many Feathers. In the 1936 Disney short, Alpine Climbers, Mickey Mouse has a run-in with an eagle. It is never explained why the Mouse wants the eagle’s eggs.

Too Many Feathers. In the 1936 Disney short, Alpine Climbers, Mickey Mouse has a run-in with an eagle. It is never explained why the Mouse wants the eagle’s eggs.

Animator Grim Natwick was assigned to supervise that scene and immediately saw that the eagle on the model sheet had just too many feathers on it. In order to save “pencil mileage”, he requested it be redesigned with fewer feathers.

Natwick told animation historian David Johnson in 2000, “There were some real tough scenes in (that cartoon). As a matter of fact, one of them that I animated of Mickey trying to steal eagle eggs and the eagle – there was a little scrap between Mickey and the eagles – they used that as a test scene for animators who came out from the East.

“They had them re-animate that (to) see how good it was. So on that particular picture not one drawing was changed, not ONE TINY THING was changed. Nothing in the picture was changed and I got a $500 bonus on that one.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

The Felix sign is a classic! I hope the Council reconsiders.

2000? Wasn’t Natwick already gone ten years earlier?

I was unclear. Johnson’s interview with Natwick was published in 2000. It was done much earlier. I was actually at Natwick’s 100th birthday party, thanks to the generosity of my good friend and former writing partner John Cawley, where Walter Lantz was pretty hilarious. The event was videotaped but unfortunately some of the more off color stuff, including some Lantz stories, were edited out of the edition that was sold.

I remember seeing the Felix the Cat sign at the Felix Chevorlet dealers while headed to USC (The University of Southern California ) for rehearsals with the USC Trojan Marching Band (which I was a proud member of) and later to the USC Football games. That sign is always a Icon for everyone working or studying at USC.

As someone who has read Jim Korkis’s Animation Anecdotes for many years, I’d like to go on record and state that the feature is always enjoyable, and that these in particular are very good anecdotes about the world of animation. Thank you.

The sign deserves to be a historical monument, because the cat sure is.