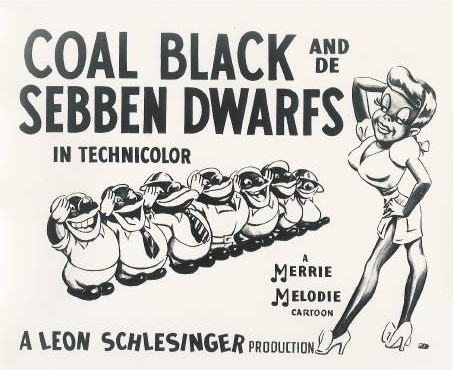

Birth of Coal Black. Animation legend Bob Clampett had gone to see a Duke Ellington revue in Los Angeles called “Jump for Joy”. After the show, Bob went backstage and talked to the musicians and performers. When they found out he did Warner Brothers cartoons, they wanted to know why black people were not used more often in them.

Bob decided to make a “black” cartoon. At the time, people were talking about “Carmen Jones” a black version of the famous “Carmen” opera. Bob looked around for another classic familiar story that could be given a “black” twist. He settled on Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”.

To research what would become Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs (1943), Bob went to the Club Alabam along with some of his animators including Bob McKimson and they immersed themselves in the culture. Some of the performers and musicians were invited to Warners to comment on the work in progress and give suggestions. Vivien Dandridge, sister of famous Blues singers Dorothy Dandridge did the voice of Coal Black. Louis Armstrong wanted to do the voice of Prince Chawmin’ but was booked on tour. He suggested drummer Zoot Watson for the part.

To research what would become Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs (1943), Bob went to the Club Alabam along with some of his animators including Bob McKimson and they immersed themselves in the culture. Some of the performers and musicians were invited to Warners to comment on the work in progress and give suggestions. Vivien Dandridge, sister of famous Blues singers Dorothy Dandridge did the voice of Coal Black. Louis Armstrong wanted to do the voice of Prince Chawmin’ but was booked on tour. He suggested drummer Zoot Watson for the part.

When it came time to do the score, Warners balked at hiring outside musicians and paying extra dollars. Carl Stalling sat down with Bob and the black musicians and carefully prepared a score which would try to capture the authentic jazz/blues flavor. In the end, probably more was spent on rehearsals than it would have cost Warners to use the black musicians in the first place. (Some of the score, most notably the trumpet solos, were done by black musicians.)

Carl Lederer. Animation legend Dick Huemer, whose animation career goes back to 1916, recalled, “There was a guy at the Mutt and Jeff studio, Carl Lederer, who thought of making an animated feature film way back in 1919 about Cinderella. This was going to be a beautiful thing but all silent, of course. He never completed it. He died. (Died November 20, 1918 of influenza at the age of 25.)

“This same fellow, Carl Lederer, also had the idea of multiplane, or putting depth into a cartoon. He took three different speeds of a background, moved them in different graduations: half inch in front, quarter of an inch farther back, one-eighth in the horizon and then the sky, tracing all three speeds on piece of paper, then going back and laboriously tracing so that when you used the traced set of papers, you got this effect of the speed in front and then less and less in the back. There was an amazing feeling of depth. We used it in Mutt and Jeff. We made two, one of a country scene and one of a city scene. And they were great! But I don’t think the audience noticed them. In general, I think, audiences were faintly hostile to the cartoons.” Here is a link to Lederer’s Patent application for his new process.

What the Heck? Storyman Heck Allen who worked for about a dozen years as a storyman for Avery at MGM stated in 1975: “Now Chuck Jones, I don’t care how brilliant Chuck is—and I’ve heard enough times that he is brilliant—he didn’t do it all by himself. He had, in Mike Maltese an extremely able gag man and a good story man. Tex (Avery) never had anybody.

“He laid the pictures out for the background man. He did everything for the so-called character man, who draws the models of the characters. If we had three pages of dialogue, he would scratch it out with his lead pencil, and I’d take this stuff and translate it into English. Tex was a bearcat for dialogue. He’d have twenty or thirty takes on a line. I couldn’t tell one from the other. But Tex would eventually pick one and I’d say, ‘Yeah! Just the one!’.”

All White. Animation designer Maurice Noble in a 1971 interview with animation historian Joe Adamson revealed: “Working with Chuck Jones was a very creative experience. It got to the point where we would have a few short-hand conversations regarding the picture and then he’d more or less say, ‘Don’t bother me. Just go ahead and do it’. And I know that sometimes he was just a little surprised at what he got back. But it worked well so he would keep his mouth shut.

“I did a character one time all painted in white. It was a woman with a white poodle, and a white umbrella, and she was all dressed in white. Everything. And I think a red rose was pinned on her. And the Ink and Paint Department thought, ‘Why, there’s no color to this character.’ Well, it looked beautiful on the screen. I’ve been fortunate enough to pull off a number of things, so that now when I do something zany, they tend to listen to me. If I can’t make it interesting, I don’t want to stick around.”

Animated Bookkeepers. “One time, when the squeeze was on (at the Disney Studio), it was decided not only to lay off some unnecessary people, but maybe to reduce some salaries. However, Walt said, ‘I want a raise for certain men, my top animators. I want them to have higher salaries’. Somebody remonstrated that it was not on the books. Walt said, ‘I can’t make pictures without those people. I can’t hire bookkeepers to draw pictures for me’,” stated Disney executive Ben Sharpsteen.

The Wrong Guy. In a 1994 interview, animation legend Andreas Deja said, “They gave me King Triton (in “The Little Mermaid” 1989), the father because he was a very dynamic, aggressive character that had to be drawn realistically. I actually based him on my own father, because when my sisters started dating it got very nasty at home. My father accused them of bringing home the wrong boys, and there was a lot of shouting and arguing. The king does the same thing. He accuses his daughter of seeing the wrong guy. So a lot of that emotional quality really came from my father.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Loved the anecdotes on the inspiration for “COAL BLACK”; I’d like to think they’re true, because Louis Armstrong would have been oh, so perfect as the voice of Prince Chawmin’. He might have even adlibbed dialogue that Clampett would no doubt have used in a director’s cut, if the lines were as saucey as those in the Fleischer cartoon, “I’LL BE GLAD WHEN YOU’RE DEAD, YOU RASCAL YOU”! Consequently, there was a Louis Armstrong-like character in “TIN PAN ALLEY CATS”; I wonder who did the voice for that! This is why we need a professionally restored copy of this film *WITH COMMENTARY TRACK*. Sure would be nice if one of the musicians on the sessions survived and remembered doing voice work for the Warner Brothers cartoon. There was a mid-period of Armstrong recordings that would neatly inspire a cartoon–not that these were campy, but the music was wild, almost the more accurate and perfect representation of a real fireball session that closes something like “SWING WEDDING”, another cartoon that I wish Louis Armstrong was part of with his Hot 5’s and Hot 7’s. I’d love to have heard the rehearsals and musical performances that may not have all been used in the actual performing of “COAL BLACK AND THE SEVEN DWARFS” for the soundtrack of that cartoon! Wow, just think of the extras! Big band fans surely must be drooling!

Never heard of Carl Lederer before. Makes you think, if not for that darn Spanish flu he might’ve given Walt a run for his money or even surpassed him!

& interesting with Coal Black. For all the people nowadays saying to burn it for racist content, it sure sounds like they tried *very* hard to get approval of the community at the time.

Regarding COAL BLACK, Stalling conferred with the Central Avenue musicians via African American bandleader & pianist Eddie Beal. Stalling delegated most of the work to his arranger Milt Franklyn. Carl Stalling was more closely involved with Beal on TIN PAN ALLEY CATS the following year. Watson played the drum solo near the end of COAL BLACK as well as doing the Prince voice. Clampett used him again in TIN PAN as the scat singer but the Fats Waller voice was by another, a black mimic heard in several other cartoons. Sody Clampett said that Eddie Beal and his brother, also a musician, remained friends with Bob Clampett for the rest of their lives. Vivian Dandridge sent Bob a letter in the 70s, thanking him for the cartoon gig! Her mother Ruby possibly auditioned for the opening Mammy storyteller…she played similar roles on radio, including Judy Canova’s maid Geranium, but the final Mammy in COAL BLACK was Lillian Randolph, best known from radio’s GREAT GILDERSLEEVE and the Tom & Jerry cartoons. For years a silly rumor said that high-voiced Ruby was the froggy voice of the Wicked Queen! Wrong! Clampett told Hames Ware in 1971 that he used Danny Webb for that role.

Was never a fan of how they made black characters looked back then. Did enjoy the way they made them move though.

Coal Black was a very funny cartoon. Once you get past the design of the black characters and some of the stereotyped humor. Look, I know Bob Clampett had the best of intentions and never meant to hurt anyone but unless explained for the historical times that they were, this kind of toon could cause a freaking riot in today’s atmosphere. Simply put, black people did NOT look like that, pure and simple. Far as I’m concerned this is still drawn in the old minstrel “darkie” mold. But on a lighter note, I did like that the little “Dopey” character was the hero!