Last week I introduced readers to the iconic ‘Direct Mass Selling’ program that the Jam Handy Organization produced for the Chevrolet Division of General Motors Corporation throughout the Great Depression, from 1935 up to 1942. In addition I gave an overview of how its documentary films utilized technical animation and showcased “Spring Harmony” (1935), “No Ghosts” (1935), “On the Air” (1937), “Color Harmony” (1938), and the week before “Down The Gasoline Trail” (1935), as examples. Here are five more one-reel ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries that beautifully showcase Rockwell Barnes’ “photography faithful” and “visualizing the invisible” technical animation, combined with other fun demonstrations from the imagination of the Jam Handy Organization. These selections consisting of “Behind The Bright Lights” (1935), “How You See It” (1936), “Water Boy” (1936), “Spot News” (1937), and “Riding The Film” (1938), all vary in topic and show the different uses of Barnes’ technical animation. In addition they also show how the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries were right on par with popular Hollywood documentary shorts of the era such as those made by Pete Smith for M-G-M and Jerry Fairbanks for Paramount. Like the Hollywood shorts, the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries provided much needed enlightenment and entertainment to many during the country’s worse financial crisis.

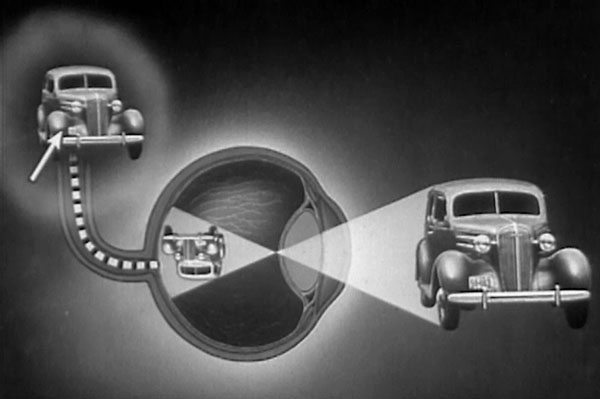

To kick off this article we’ll begin with an appropriate entry “How You See It” that discusses how the persistence of vision allows the eye to see a motion picture.

“How You See It” (1937)

JHO Completion Date: October 8, 1936

Copyright Date: January 8, 1937

Original Number of prints (as indicated by copyright records): 605

Narrator: Lowell Thomas

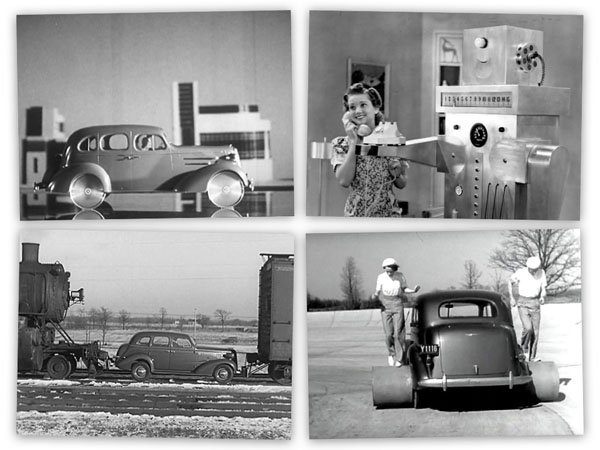

Description: Documentary that demonstrates how the persistence of vision allows viewers to watch a motion picture at their local theatre, such as a Chevrolet advertising film. Rockwell Barnes contributes technical animation and drawings showing how the human eye sends images to the brain, how the persistence of vision is made possible, and how a 35mm motion picture projector works. The advertising nature of the film is through product placement and motion picture footage of Chevrolet automobiles in action to demonstrate the persistence of vision. Two notable scenes to keep an eye (or more appropriately a ‘persistence of vision’) on that demonstrate some of Chevrolet’s features:

• 6:05- The sequence of the three performers on top of a Chevrolet automobile while it is driving over railroad ties; this shows off the ‘knee action’ which absorbs bumps in the road.

• 7:24- The stunt sequence with the Chevrolet car flipping over, created to show that the driver was unharmed during the accident. How truthful this scene is a bit of a mystery…

“Behind the Bright Lights” (1935)

JHO Completion Date: Not Listed

Copyright Date: Not registered

Narrator: Lowell Thomas

Description: Fascinating film that showcases how a large lighted Chevrolet sign in an unnamed City (but credited as being the largest sign there) is maintained, operates and projects messages through it’s ‘motorgraph’. No cars are present in this film and instead the advertising nature is kept to the Chevrolet logos and slogans on the sign. The film also promotes how technology savvy Chevrolet was in the 1930s. Rockwell Barnes’ technical animation is used to demonstrate how the Chevrolet theme “Knee Action Ride” is shown with the sign’s ‘motorgraph’.

“Water Boy” (1937)

JHO Completion Date: August 2, 1936

Copyright Date: January 4, 1937

Original Number of prints (as indicated by copyright records): 221

Narrator: Lowell Thomas

Description: A fun film that discusses the role of an automobile cooling system. This short, which masquerades as a public service on the importance of keeping a car radiator full of water, was probably directed by Frank Goldman or J. Cullen Landis as it’s similar to other films credited to them. The advertising nature of this film is kept quiet and subliminally communicates how Chevrolet motor cars feature the best efficient cooling systems. Chevrolet’s cooling technology is fully demonstrated at the end in a “real test of any automobile’s cooling system” in which a sedan “under extreme load and temperature conditions” successfully drives up one of the “longest and toughest hills in the country”, the nine mile hill located between the towns of Clarkdale and Jerome Arizona. Rockwell Barnes contributes several technical animation sequences that ‘visualize the invisible’ of how the engine cooling system works. One fun sequence that occurs at 4:17 to 5:27 is a demonstration utilizing a coffee saucer to demonstrate the concept of the cooling system, which combines live action with animation and other tricks. Samuel Benavie also provides enjoyable background music during the film’s opening (a variation on Tchaikovsky’s “Marche Slave”) and grand finale demonstration.

“Spot News” (1937)

JHO Completion Date: April 16, 1937

Copyright Date: Not Registered

Narrator: Lowell Thomas

Description: Intriguing film, that effectively demonstrates the long past technology of how photographs were sent by wiring them through the telephone. Rockwell Barnes’ animation ‘visualizes the invisible’ complex process in a manner that is easy for viewers from 1937 through 2017 and beyond to understand! A handful of Barnes’ drawings of the equipment used for the photo wiring transmission are literally ‘photography faithful’ and even fool one into thinking they are watching live action footage. Though the theme of the film does not deal with automobiles, the advertising is done with the sequence of the newsworthy stunt of an airplane taking off from the top of a Chevrolet automobile. This sequence that shows the car driving along a dirt road in a field demonstrates Chevrolet’s ‘knee action’, allowing it to smoothly launch the plane.

It should be noted that this film along with “Down The Gasoline Trail” were both highlighted in Rockwell Barnes’ obituary that “Business Screen Magazine” wrote and published in 1954.

Who needs an iPhone with a camera…

“Riding the Film” (1938)

JHO Completion Date: November 3, 1937

Copyright Date: February 14, 1938

Original Number of prints (as indicated by copyright records): 48

Narrator: Lowell Thomas

Description: A film loaded with technical animation that shows the importance of lubrication for engines. The beginning of the film features a musical stock footage montage, set to “The Skaters Waltz”, of professional winter athletes competing at the 1936 Winter Olympics. (The 1936 winter olympics were held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany which is why an infamous German flag is unfortunately seen in some shots.) The purpose of this sequence is to discuss how skiing and skating is made possible by water lubrication and introduce viewers to how lubricants contribute to their everyday lives. This is followed by a demonstration on the pros and cons of water lubrication and eventually leads into a demonstration on oil lubrication and it’s film like qualities. Rockwell Barnes contributes technical animation and drawings to show:

• how water makes ice skating possible,

• how the propeller on a boat uses water as a lubricant,

• how a perfectly engineered Chevrolet automobile engine uses oil lubrication,

The advertising nature of this film subliminally communicates how Chevrolet engines are scientifically engineered to get the most out of oil lubricants.

There certainly were other terrific documentary films made for the program, many that used very little, if any, technical animation. Instead these films relied on stunts, demonstrations, acts, etc. to effectively educate people on complex processes and entertain them. Some other notable ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries that are recommended by the author consist of:

“Get Going” (1935)

“Streamlines” (1936): Fun film on why Chevrolet automobiles of the 1930s are designed in a streamlined style. A brief animation sequence by Rockwell Barnes depicting a city of the future and the torpedo car of tomorrow is shown.

“Take It Easy” (1936): Another of the many spring themed DMS films. This film features a rather fun special effects sequence by Frank Goldman at the beginning of the film.

“Spinning Levers” (1936): A film on how the transmission of the motorcar works. This film features a cartoon sequence by Frank Goldman of a rotoscope Archimedes trying to move a stop motion planet Earth with a lever.

“Around The Corner” (1937): A film that discusses how the automobile turns. The film employs several enjoyable circus type acts to entertainingly educate viewers on this potentially boring subject.

“Seeing Green” (1937): Rather fascinating film on the traffic light, it’s current issues (of the 1930s) and the future of a national standardized traffic light system. This black & white film features a Technicolor animation sequence at the end with stop motion animation by Frank Goldman and brief technical animation by Rockwell Barnes visualizing the perfected standardized traffic light system of tomorrow.

Rube Goldberg in “Something For Nothing” (1940)

“Leave it To Roll-Oh” (1940): Fun film that was created for exhibition at the 1939/40 World’s fairs, but was also issued as a typical ‘Direct Mass Selling’ release. The film demonstrates how the switches and relays in a Chevrolet automobile are just as intelligent as a robot of the future.

“Something For Nothing” (1940): A documentary on how engines are designed to get the most out of fuel. Famous cartoonist Rube Goldberg stars in this film and features several brief animations, believed to have been done by Jim Tyer.

And many others such as Vacuum Control (1938), Remote Control (1941), Taking The Air (1941), and more! The following video below features clips of the animation sequences from “Get Going”, “Spinning Levers”, “Streamlines” and “Seeing Green”, along with the complete film “Something For Nothing” starring Rube Goldberg and narrated by Vincent Pelletier.

Reviews of many of the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentary films that would appear in trade publications such as Film Daily and Motion Picture Herald spoke highly of their storytelling and showmanship techniques. Whether or not the general public thought the same is not officially known, however for a variety of reasons its possible that they were enjoyed by many, even had their fans, and were also effective advertisement films for Chevrolet Dealers. The audiences who watched these films ranged from respectable business men, community officials, educators, students, factory workers, etc. and folks struggling financially; all of whom were dealing with the harsh realities of the ongoing great depression.

The ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries were like many other common interest theatrical documentary short subjects of the era (i.e. films by Pete Smith or Jerry Fairbanks), all of which strived to provide entertainment and escapism from the ongoing financial crisis. Seeing how similar in nature they were to other popular Hollywood documentary shorts, combined with their fascinating technical animation sequences (which neither Smith or Fairbanks utilized prior to World War II), it’s very well possible that the Chevrolet documentaries did entertain the majority of viewers. Interestingly though, in 1940 Jam Handy did go even further to make the advertising nature of the documentaries more invisible and appear as typical short subjects by removing the Chevrolet name from the credits. It’s not known why this was done exactly, if it was because the films were losing popularity due to their obvious advertising nature or if it was an experiment to use no mentions of Chevrolet and utilize only product placement to advertise the cars.

The ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries were like many other common interest theatrical documentary short subjects of the era (i.e. films by Pete Smith or Jerry Fairbanks), all of which strived to provide entertainment and escapism from the ongoing financial crisis. Seeing how similar in nature they were to other popular Hollywood documentary shorts, combined with their fascinating technical animation sequences (which neither Smith or Fairbanks utilized prior to World War II), it’s very well possible that the Chevrolet documentaries did entertain the majority of viewers. Interestingly though, in 1940 Jam Handy did go even further to make the advertising nature of the documentaries more invisible and appear as typical short subjects by removing the Chevrolet name from the credits. It’s not known why this was done exactly, if it was because the films were losing popularity due to their obvious advertising nature or if it was an experiment to use no mentions of Chevrolet and utilize only product placement to advertise the cars.

What cancelled the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ Program in 1941/2 was not a decline in popularity but the United States entering World War II in December of 1941. This was prompted by General Motors, Chevrolet, and the Jam Handy Organization going strictly into war production following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. However, even before the entering of the second World War the Jam Handy Organization had already begun mass producing military training films by the mid-1940s to help prep the military for a possible conflict. (It should be briefly noted that throughout the 1920s and up through the 1960s, the Jam Handy Organization was one of the top producers of armed forces training films; with this in mind, the Jam Handy Organization had it’s connections to know of a possible coming conflict.)

Scenes from other ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries

Interestingly the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentary films that were released throughout mid-1940 and 1941 do not feature much, if any, technical animation and several of them have sequences hinting at a possible war. The absence of Barnes’ animation in these “Direct Mass Selling” films may have had a lot to do with his much needed involvement in the production of military film projects being produced throughout 1940 and 1941. The use of his skills on these training aids were obviously far more important than on a bunch of novelty advertisement films for Chevrolet.

The last film that was released for the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ program was apparently “Magic In The Air” which was completed on December 15th, 1941 and registered for copyright on January 15th, 1942. The content of the film deals with television technology, where it was by 1941 and where it was going. It’s interesting to compare this film to the programs’ early entries such as “Spring Harmony”, “No Ghosts”, and others made throughout the years to see how the documentaries evolved. The film does feature some very brief technical animation by Rockwell Barnes’ but interestingly recycles animation from the 1937 documentary “On The Air”.

The last film that was released for the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ program was apparently “Magic In The Air” which was completed on December 15th, 1941 and registered for copyright on January 15th, 1942. The content of the film deals with television technology, where it was by 1941 and where it was going. It’s interesting to compare this film to the programs’ early entries such as “Spring Harmony”, “No Ghosts”, and others made throughout the years to see how the documentaries evolved. The film does feature some very brief technical animation by Rockwell Barnes’ but interestingly recycles animation from the 1937 documentary “On The Air”.

Unfortunately, the complete original 1942 version of “Magic In The Air” is currently unaccounted for. The only known available version of the film is a re-issue from 1945 which removes the Chevrolet advertisement sequence and replaces the original end title. This brief sequence compared the development of television to the development of automobiles. What’s provided for this article is the 1944 re-issue with a recreation by the author of how the Chevrolet sequence may have played out. This is reassembled by utilizing audio from the film’s 1955 shot by shot remake and also Chevrolet footage from other Jam Handy DMS films. (It should be briefly noted that during the 1950s Jam Handy made shot by shot, scenes by scene, and audio by audio remakes of many of there 1930s films to update them.)

During World War II and even into the 1960’s, many of the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries were offered as 16mm films by the Jam Handy Organization and by General Motors Corporation to schools, colleges, the military, etc. as educational aids. The films, especially those featuring technical animation by Rockwell Barnes, were still spoken of highly by both Jam Handy and General Motors in educational film catalogues of the 1950s and 1960s and were never hinted at being dated. Even today in 2017, while much of their content is dated to some degree, the production values and showmanship techniques that were put to use, the films still effectively educate people on the technology of the era and even on concepts that are still in use today. (That alone says a lot about Jam Handy’s filmmaking and Rockwell Barnes’ artistry!)

Trade ad for one of Jam Handy’s World War II era projects: a pilot training filmstrip series, which was produced prior to the entering of World War II. This set, like many other military and war front projects Jam Handy produced throughout 1940 and 1941, required Rockwell Barnes’ artistry and skill. Projects such as these were far more important than a series of novelty advertisement films for Chevrolet, which explains the absence of Barnes’ work in them throughout 1940 and 1941.

Rockwell Barnes certainly contributed his talents to other films outside of the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ Program and filmstrips that were produced by the Jam Handy Organization throughout the 1930s. Some excellent examples of his non-DMS work can be seen in “More Power To You” (1939), “We Drivers” (1935), “Tip Tops in Peppyland” (1934) and many others that may be discussed in the future when appropriate. Further detail highlighting Barnes’ Jam Handy work can be read in this 1942 Business Screen Magazine article (click to enlarge):

That concludes this trilogy of articles dedicated to Rockwell Barnes’ technical animation and also to the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentaries. I hope that these pieces have provided insight on what these films were, and why they’re excellent examples of documentary filmmaking from the 1930s. In addition I also hope that readers who teach film production consider using many of these ‘Direct Mass Selling’ documentary films as resources to help teach the production of documentaries and industrial training videos.

I wish to thank the many wonderful people who have assisted me overtime with the production of these three articles: Rick Prelinger, Ray Pointer, Kurt Ernst, John Rusche, Bill Sandy, Brian Oaks, and Thomas Stathes. In addition I would also like to thank Rick Prelinger a second time for making all of the films featured in this article, and many other Jam Handy productions, available to the general public. And finally I would like to extend a huge thank you to Jerry Beck for this wonderful opportunity over these past three weeks to share this research and information on these iconic films with the readers of Cartoon Research.

In the future I will be writing another mini-series of articles for Cartoon Research which will included one article on 1936/7’s A Coach For Cinderella (along with 1936’s The Master Hands) and another piece on the Nicky Nome cartoons (1941’s Drawing Account will be discussed in detail in this piece). Believe it or not, A Coach For Cinderella and The Master Hand’s are apparently Jam Handy re-adaptions/remakes of a very successful industrial film that was made by Audio Productions a few years earlier… More on that later…

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Leave a Reply