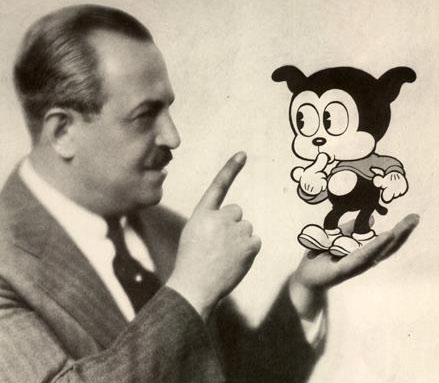

Max Fleischer and Bimbo

October 1st, 2019 is the publication date for my new book through the Minnesota Historical Society Press. It’s called Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State, and I think it’s my best book yet. While balancing work and home with book-signings in the immediate future, I thought I’d go back to sharing some more letters I received from animators of the Golden Era.

As for this column, I’m going back to how my postings began — with letters from animators. Today, from 1997, I’m offering up the reply Myron Waldman sent to my question about Bimbo.

When I wrote to former Fleischer animator Waldman in 1997, I asked him about whether Bimbo the Dog was African American, the caricatures of African American jazz musicians, and where sources for African American caricature originated. Here is his response from July 28th, 1997.

“Dear Christopher Lehman,

“Dear Christopher Lehman,

In answer to your questions–

You must realize all the early animation until the ’30s was done in black and white and shades of gray–giving the impression that Bimbo might have been a blackface character. I don’t think this was the case in Bimbo–either [in] drawing or [in] voice.

The studio using Cab Calloway & Louis Armstrong – Paramount owned Famous Music. So their use in the Bouncing Ball series was a natural marriage. The performers jumped at the chance to appear on screens all over–coverage they could not get before. Remember–no television.

Why, in my opinion, were black characters depicted stereotypically in cartoons?

It seemed to stem from every comedy stage-wise — Irish characters, Dutch, etc., & blackface minstrels, later–Eddie Cantor & Al Jolson. At the time the animated cartoons used blackfaced characters

[In answer to whether he could direct me to other ex-animators,] I don’t know any people left to help you out. There are historians of the animated cartoons. You’ll find their books available in any good-sized library.

I’m sure you’ll do well on your dissertation.

Sincerely,

Myron Waldman

To his credit, Myron Waldman himself did few – if any – cartoons containing black stereotypes. Embed below is one of Waldman’s first Betty Boop cartoons, I Heard (1933), which features a soundtrack by black jazz musician and songwriter Don Redman.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

It was very gracious of Mr. Waldman to give such a cogent and honest reply to your questions about his work of six decades earlier, when he himself was approaching his 90th birthday. By all accounts he seems to have been a wonderful man.

While there may be few black stereotypes in Waldman’s cartoons, he was lead animator on the Superman war propaganda cartoon “Japoteurs”, as well as the final Betty Boop short “Rhythm on the Reservation”.

“I Heard” is a great cartoon. I think it stands on a par with the three Calloway/Boop collaborations, and is a good deal better than “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You” with Louis Armstrong. Don Redman was a fine bandleader known for his sophisticated arrangements. The instrumental tune his band plays over the opening credits of the cartoon is “Chant of the Weed”, one of the great “reefer songs” of the Prohibition era.

As for the putative racial aspects of Bimbo, I suppose one can make a case either way. A lot of people worked on these cartoons, and their individual contributions could be inconsistent and contradictory. Even Bimbo’s design varied considerably; he could be a white dog with droopy ears as in “The Robot”, or a black dog with erect ears as in “I Heard”. In the first Betty Boop cartoon “Dizzy Dishes”, Bimbo — here, white and droopy — appears to be mimicking African American speech: “Nice, hot roast duck with the gravy just oozin’ out.” Yet in the same cartoon, a Jewish caricature demands: “I vant ham!” (and is thrown a ham with the word “kosher” marked on it in Hebrew) and a moment later, a German caricature says; “Vhere’s my knishes? Mach schnell!” In New York in the thirties, not only the diverse ethnic groups themselves, but the interactions between them and their influence on each other, were sources of humour.

Another example is from a cartoon in which Bimbo does indisputably appear in blackface, “Bamboo Isle”. After smearing dirt on his face and putting a bone through his topknot, Bimbo sings one of the Royal Samoans’ songs to blend into the native population; the natives respond by shouting “Ah, landsman! Sholem aleichem!” — a greeting, in Yiddish, to a fellow countryman.

It should be obvious, but bears repeating, that cartoons, as mainstream entertainment, reflect the typical attitudes of their time toward race and ethnicity. African Americans received the worst treatment in cartoons (as well as in real life): always the butt of jokes, and always the same jokes — stealing chickens, shooting craps, fighting with razors, shiftlessness, bad grammar — over and over again. So ingrained was this attitude that as late as 1973, a “coon song” (though it did not use that word) could become a number one hit in America without arousing comment. I refer to Jim Croce’s “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown”. Leroy shoots dice, has “a razor in his shoe”, and according to the dehumanising simile in the chorus is “Badder than old King Kong, meaner than a junkyard dog.” Nearly identical comic songs like “Big Dick from Boston” were commonplace in minstrel shows half a century earlier.

I look forward to reading your correspondence from Bob Clampett. I think he had a lot to answer for.

Unfortunately, Bob Clampett passed away well before I started my dissertation; I worked on my doctorate between 1997 and 2002.

I enjoyed reading your post as it was very informative. However, I disagree that by Bimbo rubbing dirt on his face and sticking a bone in his hair constitutes an ‘indisputable’ example of blackface. The term blackface is quite specific in its meaning: “The practice of wearing makeup to imitate the appearance of a BLACK PERSON, or to represent a caricature of a black person.”

The South Pacific native inhabitants on Bamboo Isle are Samoan, whose roots are Asian. They are not Sub-Saharan Black African, Black American, or Black Caribbean. So, in my opinion this is a clear example of ‘brownface.’

Well, apparently it’s not indisputable after all; but I’m afraid these ethnological distinctions would have been lost on the cartoonists of the thirties. Pacific Islanders were shown speaking in African American dialect (“Pop Pie a la Mode”), playing jazz (“The Isle of Pingo Pongo”), wielding razors (“Zula Hula”), and were generally indistinguishable from the African cannibals in “Trader Mickey” and “Plane Dumb”. Even though “Bamboo Isle” incorporates authentic Polynesian music and dance, the natives are shown carrying shields emblazoned with a pair of dice. The races may be different, but the stereotype — rooted in blackface minstrelsy — was the same.

Is “I heard“ one of the cartoons left off the two laser disk boxes of Betty Boop cartoons? I know there was one of these that did not show up; I can’t remember which title. This is a very interesting article, and I wonder what you Harmon’s response to this question wise?

I don’t know about the laserdisc collection, but I Heard is on Volume 4 of the VHS box set on which the laserdiscs were based.

As seems to fit his changing coloration, Bimbo seems to be whatever ethnicity was required at the time, which seems to play into a general “equal opportunity offense” approach—though it can’t be denied that the Fleischer staff were generally white and/or Jewish, so an African-American portrayal from them would be relatively less enlightened; and the notion of requiring an ethnicity at all relates, overwhelmingly, to which behaviors were seen to befit which stereotype.

Thus when a storyline requires Bimbo to steal a chicken (in SWING YOU SINNERS) or win a poker tournament (in THE ACE OF SPADES), Billy Murray is clearly, if inconsistently, trying to lay a southern African-American accent on top of Bimbo’s usual cadence; some musical choices in ACE and even its title, seemingly referencing Bimbo himself, trip over the line from equal opportunity cliche into clumsy and undeniable racism, if obscured enough to be less than obvious today.

That the racial aspect in SINNERS is easy to overlook, and that other cartoons lump Bimbo into other ethnicities with no grinding of gears, does seem to show that the ignorance at Fleischer was less mean-spirited than it appears at some other studios. But it’s hard to say there was an upside to any of this…

American Animated Cartoons Of The Vietnam Era sounds interesting. Do you include the Disney features of the period in it? For a time I had this goofy idea that King Richard’s return at the end of Disney’s Robin Hood was a reference to US soldiers returning home from Vietnam that same year (1973).

Thank you. Yes, features are included.

As “Cartoon Research” is probably not the appropriate forum to have this discussion, I must reply to the following statement by Groh: “I’m afraid these ethnological distinctions would have been lost on the cartoonists of the thirties.”

I agree, but I can assure you that the distinctions were not lost… then or now… to Black Americans. My initial response was simply to assure that the term ‘blackface’ be used correctly; in this case in regards to animation. I realize that for many folks this may seem like an insignificant point to make, but there is a historical tendency in America to gloss over, conflate, misrepresent, and even falsify terminology and issues that are distinctive on the timeline of the Black American community. Blackface and minstrel shows were American creations that had a sole purpose: to entertain White Americans by utilizing systemic racism to mock and demean African Americans, and to perpetuate stereotypical caricatures of a people who for centuries had been on the receiving end of America’s piss stream.

This type of racial stereotyping may have blossomed during the advent of 19th century minstrel shows, but the seed was deeply planted and took root hundreds of years earlier in the early 17th century with the arrival of African slaves on American soil. Yes, the races may be different, but the social, political, generational ramifications, and painful imagery of blackface is not the same — it is unique to African Americans.

Thank you for saying so. Your comment is exactly why I posted the letter–to lead to discussions about how films were made and what their content meant for the animators and for all of their viewers, including African American viewers. So, it’s very appropriate.

I agree with everything you’ve written, Jazzman, and I agree that this is an ideal forum for such discussion. It’s especially important to establish proper terminology, as you’ve done here. The point I meant to make is that, because Pacific Islanders in old cartoons were invariably portrayed as African American stereotypes, to one extent or another, then hard-and-fast distinctions between black- and brownface are moot in this particular context. Given that (1) “Bamboo Isle” is far from the most egregious example of this trope; and (2) Betty’s appearance as a dark-skinned, hula-dancing Island girl, and not an African American, cannot possibly be construed as blackface; and (3) Bimbo, having darkened his cheeks, sings a Samoan song rather than something by Stephen Foster or Al Jolson, I’ll cheerfully concede your point and accept his disguise as an example of brownface, plain and simple. But the dice on the natives’ shields are a jibe at African Americans, no two ways about it.

The Pinky and the Brain cartoon “Brainania” (1995) is set mainly on a tropical island inhabited by superstitious, spear-carrying cannibals who worship a volcano god; but their appearance and speech are modeled on those of white Australians. I personally don’t have a problem with that; but if any Pacific Islanders object to being thus characterised, I can’t say I blame them!