In 1932, Walt Disney had moved from Columbia (where he was very dissatisfied with the way they were handling his animated short cartoons) to United Artists where he had a mighty champion in the presence of actress and co-founder Mary Pickford.

Walt had wanted to move into producing cartoons in color and now he had the opportunity since United Artists was willing to share in the cost.

However, Walt proceeded with caution and only asked to make one cartoon in Technicolor to see how it would be received by audiences. As a back-up in case anything went wrong, he agreed he would also produce a full black-and-white version as well which he did and showed United Artists executives to get final approval.

Of course, animation legend is that after completing the Silly Symphony Flowers and Trees (1932) in black-and-white, Walt scared his brother Roy O. Disney by declaring that he was going to throw the whole thing away and start over using the more expensive process of Technicolor.

As colorful as this anecdote is and is often repeated as part of official Disney history, documents show that it was part of Walt’s agreement with United Artists to produce a black-and-white version as well. It was not a visionary after-thought to re-do the entire film in color.

The conversion the film to a color version took roughly an additional three months. Actually, to help control costs, the gray and white paint was carefully wiped off the back of the existing cels (with the black line remaining) and then a range of colors were repainted on them.

Bob Thomas wrote in his terrific book Walt Disney: An American Original: “After the first few scenes had been completed (in color on Flowers and Trees), Walt showed them to a friend, Rob Wagner, publisher of a literary magazine in Beverly Hills (Script magazine). Wagner was so impressed that he invited Sid Grauman, impresario of Grauman’s Chinese Theater to see the film.

“The film lasted only a minute, but Grauman said he wanted Flowers and Trees to open with his next attraction, (MGM’s) ‘Strange Interlude’, starring Norma Shearer and Clark Gable. Walt worked his animators overtime to finish ahead of schedule, and Technicolor sped the processing.

“When Flowers and Trees appeared at the Chinese, in July 1932, it created the sensation that Walt had hoped for. No longer was the Silly Symphony the neglected half of the Disney product. Flowers and Trees got as many bookings as the hottest Mickey Mouse cartoon. Walt decreed that all future symphonies would be in color.”Actually, it was more complicated than that. United Artists, despite the success of the film critically and financially, balked at the additional cost but begrudgingly approved three more color Silly Symphonies. Eventually, that commitment became six and then the entire series because of the overwhelming success of them.

According to the October 1934 issue of “Fortune” magazine, Merian C. Cooper, producer for RKO Radio Pictures and director of King Kong (1933), “saw one of the Silly Symphonies and said he never wanted to make a black-and-white picture again.”

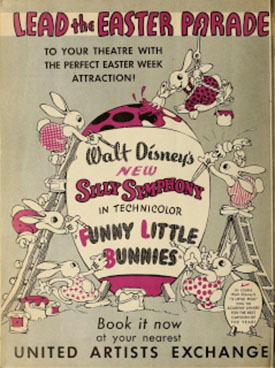

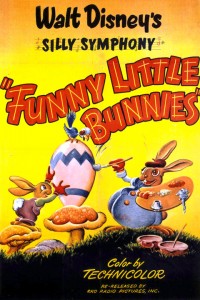

However, the true gem to demonstrate the power of Technicolor was another Silly Symphony short, Funny Little Bunnies released March 24, 1934. It was the only Disney animated short cartoon about Easter made during Walt’s lifetime and some feel it should be more accurately titled “Cute Little Bunnies” since the rabbits at best induce just a smile or mild chuckle.

Directed by Wilfred Jackson, it is a simple glimpse into the magical land of Easter Bunnies and how they prepare their colorful eggs for delivery. There were no villains trying to steal the eggs or natural disasters threatening the production or any other intense issue. It was just basically bunnies coloring eggs.

The eggs were indeed colorful, especially considering that for Flowers and Trees United Artists insisted, in order to save costs, that no more than a maximum of twenty colors could be used. For this cartoon the entire palette was applied.

In fact, Technicolor used Funny Little Bunnies for several years as its example of what could be accomplished with its process in capturing the widest possible visual spectrum.

Below is the text from an address entitled “Technicolor Adventures In Cinemaland” made by Technicolor founder Herbert Kalmus at the Fall meeting of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (Now SMPTE) in Detroit, Michigan on October 28, 1938.

“What Technicolor needed was someone to prove for regular productions, whether short subjects or features, what Disney had proved for cartoons. But the producers asked, ‘How much more will it cost to produce a feature in three-component Technicolor than in black and white?’

“This question is always with us and it seems to me the answer must be divided into two parts; the added cost of prints, negative raw stock, rushes, and lighting can be numerically calculated and requires little discussion. But then there are the less tangible elements about which there is much discussion.

“This question is always with us and it seems to me the answer must be divided into two parts; the added cost of prints, negative raw stock, rushes, and lighting can be numerically calculated and requires little discussion. But then there are the less tangible elements about which there is much discussion.

“I have said to producers and directors on many occasions: ‘You have all seen Disney’s Funny Bunnies (sic); you remember the huge rainbow circling across the screen to the ground and you remember the Funny Bunnies drawing the color of the rainbow into their paint pails and splashing the Easter eggs. You all admit that it was marvelous entertainment. Now I will ask you how much more did it cost Mr. Disney to produce that entertainment in color than it would have in black and white?’

“The answer is, of course, that it could not be done at any cost in black and white, and I think that points to the general answer.

“A similar analogy can be drawn with respect to some part of almost any recent Technicolor feature.

“If a script has been conceived, planned, and written for black and white, it should not be done at all in color. The story should be chosen and the scenario written with color in mind from the start, so that by its use effects are obtained, moods created, beauty and personalities emphasized, and the drama enhanced.

“Color should follow from sequence to sequence, supporting and giving impulse to the drama, becoming an integral part of it, and not something super-added.

“The production cost question should be, what is the additional cost for color per unit of entertainment and not per foot of negative. The answer is that it needn’t necessarily cost any more.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

The new book “The Dawn of Technicolor” published by the George Eastman House has an extensive discussion of “Flowers and Trees” and the production of the cartoon, putting in the context of the time when the firm was having a great deal of trouble selling its new process to the major studios, owing to issues that had arisen in 1929-1930 over quality control.

Interesting. does this black and white version of ‘Flowers and Trees’ still survive? And why didn’t they just refilm or copy the color version on black & white stock? Would the shades of gray lack contrast?

While Black and white prints were made from color films, it was obvious that the color version had more value, and the reactions to FLOWERS AND TRESS created the color cartoon market. It should be remembered also that this was the depths of The Depression. Technicolor had been shopping the process around to all of the majors, including Paramount. And as all of you know, Max Fleischer was animation producer for Paramount. Fleischer was denied the use of Three-color Technicolor due largely to Paramount’s financial restructuring after having survived their first two bankruptcies.

While it is certainly clear that Disney’s signing with UA signaled his period of artistic growth. It was not so much UA backing him in the Technicolor venture, but their connecting him with The Bank of America for financing. THIS was the major reason why Disney was able to advance as an independent compared to Fleischer, who was bound by Paramount’s financing. Of course, after two years, Paramount realized the value of color cartoons on their theatrical program, seeing how Disney had created their market.

Thank you, Mr. Korkis, for this wonderful article! It is so full of the kind of background information that I love to read!

Because of a Little Golden Record, I have known the song “Funny Little Bunnies” since I was six years old in 1951 (which was decades before I ever saw the film)! The record was issued with no songwriter credits on the label. But I feel that this song ranks right up there with “Some Day My Prince Will Come,””The Second Star to the Right,” and “Feed the Birds” as one of the most beautiful songs ever to come out of that studio! It took a little digging in Mike Murray’s splendid discography THE GOLDEN AGE OF WALT DISNEY RECORDS 1933-1988, but I finally determined that the “Funny Little bunnies” song was the work of Frank Churchill and Leigh Harline. Since they are both listed in Wikipedia as composers, I am not sure which of them wrote the lyrics, or if they collaborated completely on words and music. If anyone can sort that out and tell me who did what, I wold greatly appreciate it.

I am no Greg Ehrbar, the esteemed Disney Musicologist and my good friend, but I do know that the song “See the Funny Little Bunnies” has music by Frank Churchill and lyrics by Larry Morey. The main title music was also written by Churchill but the rest of the score was written by Harline. All sung, of course, by The Rhythmettes (a vocal group that included Mary Moder and Dorothy Compton) with Florence “Clara Cluck” Gill doing the singing chickens.

I learned something new–I always believed the old story about the color version of “Flowers and Trees”. Interesting that the color and b/w versions were part of the same package deal.

Notice how the credits for the bunny short were refilmed during the RKO Radio Pictures era to remove all trace of United Artists? Wish we could see the original titles.

So, let me see if I get this straight. The black and white version of Flowers and Trees was fully completed. But was it ever shown at the theatres, and does it survive?

Also, was Flowers and Trees the first Silly Symphonies cartoon produced after the switch to UA (which is said agreed to double the animation budget)? I remember reading somewhere that The Bears and the Bees and Just Dogs were distributed by UA, but produced while Disney still had a contract with Colombia.

And Leonard Mosley mention in his book “Disney’s World: A Biography” that Disney was so disappointed by Flowers and Trees, which was based on a concept he just throw together before leaving for vacation, that he wanted to just through it all away. But then changed his mind after he saw the color process and was in a good mood after his wife told him she was pregnant. Is any of this correct?

As I recall in my research, Disney still had a distribution agreement with Columbia that extended an additional two years after the Columbia production contract expired and he went with UA . So Columbia was still distributing Disney’s older cartoons while his new product was being released by UA. The went that agreement ended, the story has it that Columbia did not return all of the original negative elements and sent some inferior duplicate materials, which explains why many of the early Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies look grainy, high in contrast, and have such poor soundtracks, some being on discs and not the original film soundtrack rolls.

I am from Brazil

In the 50ths my grandfather use to show us very old cartoons

One is verry much like “funny little bunnys” but diferente

It was back and withe

The color was take from flowers

The eggs came from a pipe and the bunnys take it in line

A huge egg Comes to á little bunny

It was

a 16 mm movie

Do you know the cartoon?

Here are a couple of late details that are puzzling. According to what I’ve read from Bob Thomas’ writings, it wasn’t so much that Walt was” very dissatisfied with the way they (Columbia) were handling his animated short cartoons,” but their being late on paying and his having to see Harry Cohn about their delinquency, only to be told, “Young man, you’ll lucky if you get paid at all.” These interruptions in cash flow resulted in periodic layoffs with Walt and Roy taking pay cuts.

Another issues that doesn’t make sense if United Artists requesting the limit to 20 colors to save money. If that referred to the cel painting process, that is not as clear since by Depression era wages, it was immaterial how many colors were painted on a cel. And the number of colors used had nothing to do with the expense of Technicolor since the film only photographed (through Panchromatic Filtration) whatever colors were in the art. The resulting colors were part of the film process that would reproduce three colors as well as 50 if used.