Somehow, the portal into the Avant-Garde begins with a big, burly guy named Bull Dozer who merely wants to exact revenge on Woody Woodpecker. The resulting animated mayhem is a metaphor for Shamus Culhane, who directed The Loose Nut (1945) with a bit of modernist mischief. As busy as Culhane always was at the Lantz studio, he rallied his energy after long days at work and then found his bliss as an attendee of events at the American Contemporary Gallery.

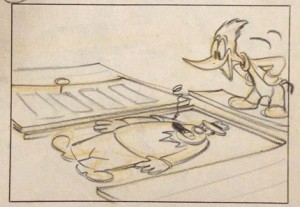

On any given Friday evening, he would go out the studio door on Seward Street and head north to Hollywood Boulevard, then through the door of this gallery to an alternate dimension of sorts. In The Loose Nut, Bull Dozer retreats and hides in a supply shed after Woody takes the wheel of a steamroller to crush him. Thinking the danger has passed, this construction worker carefully opens the shed door when suddenly a barrage of abstract imagery crashes the silence.

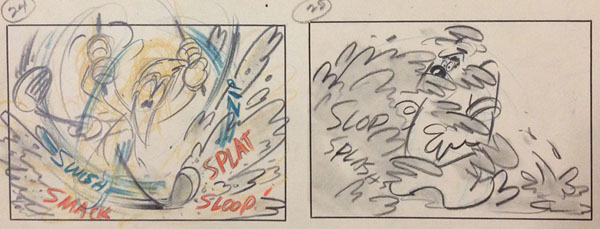

It begins with a pan-and-zoom of Woody and the steamroller advancing, painted all black with white outlines. This is followed by a jumble of shots to convey the tumbling chaos—shaking camera, wood planks flying, gleeful Woody, and the tortured face of Bull Dozer rotated fully around under camera. We see ribbons of red, blue and yellow paint strokes and a ringed planet with a burst of wavy lines streaming behind it like an eruption of debris.

What in the name of Picasso is going on here in Cartoonland? I have written about this anecdote here before, but the larger context and the fuller details tell an amazing story about a turbulent time. Politics. Social upheaval. War. Modernism. Montage. Idealism. And the brash violence and the bright colors at the center of conflict? Woody Woodpecker!

Let me formally announce what a few of you have known for the last few months. I am currently the curator of a gallery exhibit that is readying to open to the public on September 22 for a two-month run at the Laband Art Gallery in Los Angeles. The show is titled “Woody Woodpecker & the Avant-Garde” and I promise it will be quite like no other exhibit you’ve ever seen.

It will be a fitting way to remember and to celebrate the American Contemporary Gallery, a remarkable way station for the nascent community of Avant-Gardists who found much needed inspiration and camaraderie there in what Culhane deemed an oasis in “the town [that] was really a cultural desert as far as the graphic arts were concerned.” And so it will be—almost seven decades after the original was shuttered—a gallery exhibit to celebrate the influence of a long-ago and short-lived gallery.

Interior view of Clara Grossman and Barbara Byrnes’s American Contemporary Gallery in Hollywood in the late 1940s. Image courtesy of James Byrnes

There were selected screenings that one would expect of this art milieu—films by Man Ray, Oskar Fischinger, Jean Cocteau. However, there were also movies that might be regarded as straight-up Hollywood fare from the Silent era. In the 1940s, those early years of cinema were not actually so far removed, and it was not unusual to find that an older gentleman seated there was the director of the film being screened.

By Grossman’s invitation, these guests would discuss the Silent movies they had directed years before, and it was interesting how these were received by a crowd of younger aspirants hoping to break into cinema or a livelihood in the fine arts. Kenneth Anger and Curtis Harrington were regularly attending as teenagers. Maya Deren was sometimes present, as were Faith Hubley (known then as Faith Elliot), John and James Whitney, among others.

In the popular view of most Americans then, Silent Movies had become clunky, old-fashioned relics. However, to this room of assembled cinéastes, these films were a treasured link to a gloried past, a time before sound had RUINED the supremacy of the image. Modernism was regarded as a breakaway from classical forms, but in the flickering Friday Night light of this darkened gallery, there was an entirely different sentiment brewing.

Some among them looked to these old films for inspiration—to recapture what this art form had lost. Eisenstein, Griffith, Lang, Kirsanov, Wiene, and even Mack Sennett were revered. In fact, D.W. Griffith made his home in a room at the Knickerbocker Hotel just down the way on Hollywood Boulevard. The old man was a lurking giant of cinema whose classic films would presumably arrive from New York City like all the rest of them: train-bound loaners from MOMA’s movie collection.

As the film historian David James described to me, Maya Deren was a champion for the cause, stirring the idea that “sound in film would destroy visual complexity.” Her relatively brief stay in Los Angeles is forever marked by the landmark experimental film that she made there: Meshes of the Afternoon. Whether or not Meshes was shown at the American Contemporary, its two most fervent teenage patrons, Anger and Harrington, were both so awestruck by it that they each thereafter made tribute films with similar “somnambulist” themes.For a detailed look at the changing landscape of experimental cinema and the vast influence of Maya Deren, there is no better source than David James’ The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles, published by the University of California Press, and available in both hardcover and softcover. Without the work of David James to precede me, I would have never gotten as far as I did in understanding the community that inspired Culhane.

Deren returned to New York, but the fire she lit in 1943 found its strongest adherents among the film crowd brought together by Clara Grossman right under the hot lights of the Hollywood studios. Last year in this column I wrote about the parallels between Culhane’s Barber of Seville and Deren’s Meshes, both made at roughly the same time within two miles of each other.

You might think it’s a stretch, just an animation professor trying to make his theoretical connection a little too seriously, but there is no arguing that Deren’s film was an Avant-Garde sensation. In fact, there was later a surge in what became known as “trance films,” an entire subgenre of post-Meshes imitative surrealist cinema. And first among Deren’s acolytes were Curtis Harrington with Fragment of Seeking (1946) and Kenneth Anger with Fireworks (1947).

Or were they first? Did Shamus Culhane beat both of these young filmmakers to the punch by releasing Woody Woodpecker in Barber of Seville contemporaneously with Meshes? He sat right there in the American Contemporary along with Deren and these two precocious teenage admirers of her work. He took part in the discussions and he was part of the zeitgeist of their movement.

Of course, a Woody Woodpecker cartoon could never have had the full brooding tone and zombified psychosexuality of Deren-Anger-Harrington, but that was a constraint that Culhane had to work within, only putting in just enough Avant-Garde to dabble with the palette of Soviet montage and surreal temporality that others would more fully explore. After all, he still needed to serve up a Lantz studio cartoon, with all that entailed.

Of course, a Woody Woodpecker cartoon could never have had the full brooding tone and zombified psychosexuality of Deren-Anger-Harrington, but that was a constraint that Culhane had to work within, only putting in just enough Avant-Garde to dabble with the palette of Soviet montage and surreal temporality that others would more fully explore. After all, he still needed to serve up a Lantz studio cartoon, with all that entailed.

For his very last film he directed there, Culhane punked the Cartoonland status quo and slipped in flicker films of abstract art. These appeared as explosions during The Loose Nut, playing to millions of American moviegoers, a far bigger audience than Deren could have aspired to reach. The infectious spirit of the American Contemporary Gallery was pulsing its way into the Hollywood pipeline.

It’s no wonder that Bull Dozer got steamrolled by Woody into that vortex of modern art. After a jangled ride through a genre artistique, however brief, the dust settles and a crushed door opens on the ground. The storyboards by Milt Schaffer and Bugs Hardaway showed the before and after, but everything in-between was improvised by Culhane.

It’s no wonder that Bull Dozer got steamrolled by Woody into that vortex of modern art. After a jangled ride through a genre artistique, however brief, the dust settles and a crushed door opens on the ground. The storyboards by Milt Schaffer and Bugs Hardaway showed the before and after, but everything in-between was improvised by Culhane.

The result was something that the story team captured as a perfect visual metaphor. When Shamus Culhane started attending those gallery screenings, he was spun, tumbled, inspired, elevated, challenged and flattened. The door to the American Contemporary swung outward and he was perhaps a different man than the one that went in. Hopefully, this fascinated venue will be fully revealed and the gallery’s place in history restored with the opening of “Woody Woodpecker & the Avant-Garde” this September.

Among the people to thank for generous help with aspects of this exhibit are none other than my fellow Cartoon Research columnists Steve Stanchfield, Mark Kausler, and Thad K. I also have to acknowledge the enormous contribution of my collaborator in this endeavor, Laband Art Gallery director Carolyn Peter. There will be a number of public events held in conjunction with “Woody Woodpecker & the Avant-Garde” that will be announced soon, but please mark your calendar to attend a conversation I will moderate with Prof. David James of USC on the Loyola Marymount University campus: School of Film and Television, room 310, October 20, 7:00pm.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Didn’t the other Walt’s studio do similar abstract stuff in some of their films (i.e. the first sequence in “Fantasia”, the sequence in “The Three Caballeros” where Donald gets caught in the soundtrack) or is that considered a different type of abstract stuff?

Yes, to his great credit, that “other Walt” certainly very impressively explored the crossover of animation and Avant-Garde, especially in Fantasia. In this exhibit, there will be two items from Jules Engel’s work on Fantasia on display, as well as two films from Fischinger, one by Mary Ellen Bute, and so much rare and revealing Lantz animation production art (and cartoons in hi-def, an effort being helmed by none less than Steve Stanchfield!) that I think this will be a treat for anyone who visits during its run from Sept to Nov.

Pink Elephants On Parade from Dumbo is one of my favorite Disney avant-garde moments. Also enjoyed Culhane’s Woody cartoons tremendously!

Great article, thanks Tom. Hope the exhibit draws a crowd!

Fascinating piece, as always. I’m always delighted when I see a new Tom Klein article on CR.

One statement here puzzles me:

“For his very last film he directed there, Culhane punked the Cartoonland status quo and slipped in flicker films of abstract art.”

Culhane directed four more Lantz cartoons after “The Loose Nut.” Only “Mousie Come Home,” released in 1946, has any small traces of the vibrant, aggressive filmmaking we see in “Loose Nut,” but there is a relaxation of style in the final films. If you mean that you consider “Loose Nut” to be Culhane’s last major work at Lantz, you’re right. The wording suggests that these final four films don’t exist!

Everyone here forgets to mention Hoppin and Gross’ “La Joie de Vivre” (1934)

Imagine that. Woody Woodpecker on exhibit in a serious art museum. Somewhere, Walter Lantz must be smiling. (He usually was, of course…)