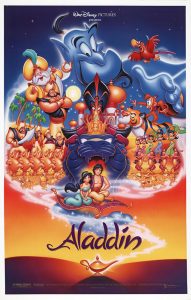

Aladdin was a game-changer. Three decades after the film’s debut, with so many animated films that followed similar sensibilities, it’s easy to forget just how unique Aladdin was when it came out.

The film’s look, tone, and all-around irreverence had never been seen before in animation, especially at Disney. Much of this came from the casting of the comic brilliance of Robin Williams, whose performance helped craft the Genie, one of the studio’s most memorable and now iconic characters.

The film’s look, tone, and all-around irreverence had never been seen before in animation, especially at Disney. Much of this came from the casting of the comic brilliance of Robin Williams, whose performance helped craft the Genie, one of the studio’s most memorable and now iconic characters.

The Genie, and the entire film Aladdin, took Disney and the animation industry in a new, different direction.

Nathan Rabin, a writer with Rotten Tomatoes, discussed this on the site in 2017: “It’s not too much of a stretch to say that the history of American animation can roughly be divided into pre-Aladdin and post-Aladdin eras. Though the film rode the wave of late 1980s/early1990s Disney hits like The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, it also represented a bold new beginning. After Aladdin, animated movies became increasingly star-driven.”

Aladdin began life at Disney in 1988 when lyricist Howard Ashman submitted a 40-page treatment of a musical adaptation of the classic story from the book One Thousand and One Nights. This original version was much different than the Aladdin we know today. In this version, Aladdin had a mother and three friends, Babkak, Omar, and Kassim, and Princess Jasmine was fashioned as spoiled rotten.

Ashman and his partner Alan Menken, who changed the Disney animated musical with their Oscar-winning work on The Little Mermaid (1989) and Beauty and the Beast (1991), had penned six songs, including “Proud of Your Boy,” a ballad Aladdin sings about how he longs to make something of himself; “Babkak, Omar, Aladdin, Kassim,” a song of friendship and Jasmine’s “Call Me A Princess,” in which she sings about how she loves the finer things in life.

John Musker and Ron Clements, who, with Ashman and Menken, had steered Disney into their animation renaissance of the 1990s with The Little Mermaid (1989), were forced to re-work the story when certain aspects weren’t coming together during the early days of production.

The characters of Aladdin’s mother and best friends were taken out of the plot, and the persona of Jasmine shifted to that of a more confident character. And these changes also meant that, unfortunately, several of the songs that Ashman (who sadly passed away in 1991) had created for Aladdin would also need to go. Broadway veteran, lyricist Tim Rice (Evita), came on board and, with Alan Menken, fashioned new songs.

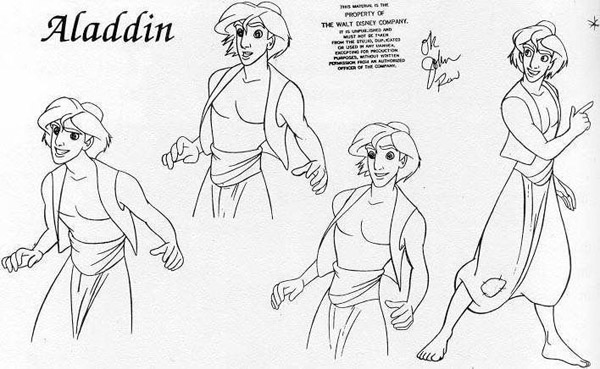

Musker and Clements wanted Aladdin to be infused with a contemporary sensibility. The directors brought animator Eric Goldberg into the film. Goldberg, who had been animating since he was a teenager, would serve as the Genie’s supervising animator and create character designs. For inspiration, Goldberg turned to one of his artistic heroes, Al Hirschfeld, most famous for his caricatures of Broadway actors and singers that appeared in The New York Times.

Musker and Clements wanted Aladdin to be infused with a contemporary sensibility. The directors brought animator Eric Goldberg into the film. Goldberg, who had been animating since he was a teenager, would serve as the Genie’s supervising animator and create character designs. For inspiration, Goldberg turned to one of his artistic heroes, Al Hirschfeld, most famous for his caricatures of Broadway actors and singers that appeared in The New York Times.

“His work is eminently animatable,” said Goldberg of Hirshfeld in a 1999 interview. “What he gets into a still drawing are the things that we strive for in animation. His work has elegance, simplicity, and suppleness of line.”

Hirshfeld’s art also informed the film’s production design, as it segued nicely with that of Arabic calligraphy, which was a major inspiration for the look of Aladdin.

The film tells the tale of the title character, a “street rat” (voiced by Scott Weinger, with Glenn Keane as supervising animator). He is tricked into attempting to get a magic lamp from the Cave of Wonders by the villain Jafar (the voice of Jonathan Freeman and Andreas Deja as supervising animator) and his parrot, Iago (Gilbert Gottfried providing the voice and Will Finn as supervising animator).

The film tells the tale of the title character, a “street rat” (voiced by Scott Weinger, with Glenn Keane as supervising animator). He is tricked into attempting to get a magic lamp from the Cave of Wonders by the villain Jafar (the voice of Jonathan Freeman and Andreas Deja as supervising animator) and his parrot, Iago (Gilbert Gottfried providing the voice and Will Finn as supervising animator).

Aladdin gets the lamp, and with it, he discovers a Genie (Williams) who can grant him three wishes. He wants one of these to become a prince so he can win the hand of Princess Jasmine (voice of Linda Larkin, with the singing voice of Lea Salonga and Mark Henn as supervising animator), whom he met while she was in disguise and roaming the streets of Agrabah.

Jasmine’s father, the Sultan (actor Douglas Seale’s voice and David Pruiksma as supervising animator), is attempting an arranged marriage for Jasmine, who, instead, wants to control her own life and destiny and marry someone that she loves. Her character is one of the differentiators in Aladdin, as the film’s message speaks to how we should be proud of who we are and not feel the need to change for anyone.

Another, and probably the biggest, change for Disney animation was the casting of Williams as the Genie. Musker and Clements knew early on in production that they wanted the comedian to voice the character.

Another, and probably the biggest, change for Disney animation was the casting of Williams as the Genie. Musker and Clements knew early on in production that they wanted the comedian to voice the character.

Goldberg took audio of one of Williams’ stand-up routines about schizophrenia and animated the Genie in a sequence around it. When Williams saw this, he signed on. And during his first twenty-five recording sessions for Aladdin, he gave the artists twenty-five different takes.

Thanks to Williams’ ingenious, stream-of-consciousness performance, the Genie transforms into everyone from Groucho Marx to Jack Nicholson and from a game show host to a flight attendant. Through it all, the brilliance of animator Goldberg keeps up with all the rat-a-tat movements, providing us with some of animation’s most memorable moments.

These moments were also unique for Disney. Previous fables and fairy tales steered away from modern references, while Aladdin embraced them. This irreverence also carried over to all areas of the film, particularly in moments with Gottfried’s Iago (realized with hysterical hyperactivity by animator Finn).

These moments were also unique for Disney. Previous fables and fairy tales steered away from modern references, while Aladdin embraced them. This irreverence also carried over to all areas of the film, particularly in moments with Gottfried’s Iago (realized with hysterical hyperactivity by animator Finn).

Released on November 25, 1992, Aladdin came in behind Home Alone 2: Lost in New York at the box office. However, word-of-mouth momentum grew, and by Christmas week, the film became the number one movie in America and eventually the most successful film of 1992.

On its thirtieth anniversary, reflecting upon Aladdin, the film’s impact cannot be understated. Not only was it another high-water mark for Disney, as their animation renaissance would truly gain momentum with this film and continue to soar over the next several years with The Lion King and Pocahontas, but it also allowed for artistic growth within the medium.

In his book, Disney’s Aladdin: The Making of the Animated Film, the late great writer and Disney historian John Culhane summed the film up best when he wrote:

“In this house of the human spirit, there are many mansions. Animation lives in one of them, and currently, the characters from Aladdin are holding a celebration there. It is a celebration that harmonizes Hamlet’s “what a piece of work is a man!… in moving, how express and admirable!” With Puck’s “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” Yet even Shakespeare never said a better than Disney’s Genie: “So why don’t you just ruminate whilst I illuminate the possibilities!”

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

As regards to the celebrity caricatures, I thought they were a mistake then, and I still do. I remember seeing Aladdin during its initial release and thinking, “Yeah, these are funny NOW, but in a few decades who’ll know who the hell Arsenio Hall or William F. Buckley were? This film will be the equivalent of a Thirties Warner Bros. cartoon with kids scratching their heads at references to Ned Sparks and Edna May Oliver. They just date the film instead of giving it a timeless quality–IMO anyway.

So? That’s doesn’t stop the enjoyment of the film. I didn’t recongize most of the caricatures in “Hollywood Steps Out” (1941) as a kid, but I still enjoyed it.

A short is one thing. Disney animated features, on the other hand, really should be ageless. And I enjoyed and appreciated the movie’s other qualities.

I understand what you’re saying, and you make an interesting, worthwhile point. A lot of classic animated films have lasted and endured in the public consciousness because they are essentially timeless. Contemporary references fade and become obscure over time; popular culture jokes date very fast.

[That said, I do treasure the sly allusion to the Trylon and Perisphere in PINOCCHIO.]

But after reading your comment, I found myself wishing that Williams’ energetic performance had somehow managed to reference Ned Sparks!

Personally, I think “timelessness” is something of a myth; yes, some things age better than others, but all work shows its age in one way or another, good ways and bad.

That aside, I was a kid in England when this film was new, and didn’t find out who Arsenio Hall was until Martial Law started airing here in my teens, and didn’t really know who Buckley was until I was pushing 30; neither stopped me watching the film many times. They are quick-fire gags that don’t take away from the film, and the Buckley impression is honestly funny even if you don’t know who that is. They’re more akin to Bugs Bunny quoting from a now obscure radio show than they are something like Hollywood Steps Out.

With all that said, if I’d seen this in the theatre as an adult at the time I might have felt the same way, as I’m certainly not above being annoyed by excessive trendiness.

I wasn’t bothered or annoyed by the impressions–I simply feel it was bad judgement to use them. Same as with having one of O’Malley’s pals be a hippie in The AristoCats (a movie set in 1910), or Baloo’s Rat Pack-ish lingo in The Jungle Book. Using trendy references will always get you an easy laugh, but I think it hurts the films in the long run.

It is unfortunate that the book came out after the well-publicized falling-out between Robin Williams and the Disney Studio, as Williams’ name is not mentioned and his contribution to the film is therefore minimized–although references are made to him, just not by name. Still, it makes for awkwardness in a book that is otherwise a valuable reference source. Fortunately, by the time of the second direct-to-video sequel “Aladdin and the King of Thieves”, Robin was back in the Disney fold and voicing the Genie once again.

As a franchise, Aladdin certainly had a long life–a theatrical feature, a direct-to-video sequel, a TV series, bookended by another direct-to-video sequel, and a Princess short featuring Jazmine. I may have left something out, but this output shows that Aladdin remained a viable property for Disney for several years.

There also the Tokyo Disney Sea 3-D live show “Magic Lamp Theater” where Eric himself did the computer animation of the genie.

Also, a Hercules crossover episode, a live-action remake, and several stage adaptations. (Side note: the 2011 Broadway adaptation features a few of the songs that were cut from the movie, including “Proud of Your Boy” and “Babkak, Omar, Aladdin, Kassim”)

The modern world did occasionally intrude into Disney’s fairy tale features, although certainly not to the same extent as in “Aladdin”: for example, the references to television at the end of “The Sword in the Stone”. When J. Worthington Foulfellow tries to convince Pinocchio there’s something wrong with him that only a visit to Pleasure Island can cure, he concludes a long string of pseudo-medical gobbledygook with the diagnosis: “You’re allergic!” This was a brand new and imperfectly understood medical buzzword at the time; I have a dictionary from 1938 that doesn’t even have an entry for the word “allergy”. The line would have evoked a huge laugh from the audience back in the day, but it lost its edge a long time ago.

He scats too! “Why this makes perfect sense!”

Never would have thought to connect Al Hirschfeld, Arabic calligraphy and Disney’s Aladdin, but once it’s mentioned, it seems so obvious.

And just think of all the artists* who contributed to the success of “Aladdin,” as well as the other features of that era (which led to the direct-to-home-video sequels, live-action remakes, and Broadway musicals–money spinners all), who got unceremoniously thrown out ten years later (without so much as a severance package) when CGI took over. You’re welcome, Disney! Same to you, Animation Guild! But that’s show biz, as they say: when they no longer need you, they no longer need you, and won’t even remember ever having needed you.

*including the one I’m married to

In retrospect it’s truly shocking how short the gap was between this era of unprecedented Box-Office and Production for Traditionally Animated films in the US and Hollywood declaring the traditionally animated film dead. As someone who wasn’t following Box Office or Industry News at the time, when I was sat watching Fantasia 2000 during its run at the London IMAX Cinema I never would have guessed it represented a tradition that would be dead just a few years later.

Geez. I’m pretty sure tradtional animated films will come back in style soon. I feel like audiences are ready for something new and I recall hearing Disney hiring and training new tradtional animators (although, I don’t know the current status of the process with the recent financial shake-up at the company).

It lives yet – mark my words! (Or just mock my words.)

Cuphead, the game, revived huge interest in it in the younger generations. And pencil test gifs are quite the rage on Pinterest, just to name one place. I think lots of us animate when we can just for fun, just to make drawings move – but I think the hand drawn stuff will experience periodic revivals. I hope some will match the 90s boom before I’m gone!

2D is dead, as far as I can tell. Any worth these drawings had has been completely lost in the public’s mind and even the people who make them. That’s what nothing but Family Guy has done to us.

I miss Robin and Gilbert a great deal.