Walt Disney

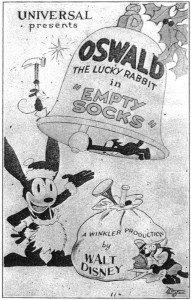

In brief, producer Charles Mintz wrested control of the Oswald production staff in 1928, making Disney travel to New York to receive his ultimatum in person. Disney was devastated by the ensuing dissolution of his staff, but as fate would have it, he sketched Mickey Mouse on the train ride back to Los Angeles. The rest is the stuff of legend, a true story with a dash of myth-making and pixie dust.

From that point on, the Lantz narrative simply cannot compete with the grand strokes of Walt’s destiny, but in many ways Oswald perfectly reflects the state of American animation in the late 1920s. The ultimate winner of this high-stakes game was not easy to discern at the time. George Winkler, who ran Mintz’s Hollywood division, quite easily lured away most of Disney’s animators with the promise of a renewed contract on this cartoon series.

Oswald thus continued under Winkler, worked on by animators like Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, Friz Freleng, Tom Palmer, Ben Clopton, and Walter Lantz, who joined in 1928. At this point, Lantz did not have a strong influence on the series. Harman was the ranking production supervisor, and Lantz’s imminent advancement to the top of the Oswald unit was mostly the result of his effective “schmoozing” with Hollywood elite.

Oswald thus continued under Winkler, worked on by animators like Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, Friz Freleng, Tom Palmer, Ben Clopton, and Walter Lantz, who joined in 1928. At this point, Lantz did not have a strong influence on the series. Harman was the ranking production supervisor, and Lantz’s imminent advancement to the top of the Oswald unit was mostly the result of his effective “schmoozing” with Hollywood elite.

After all, during the immediate post-Disney period—and even when Disney was at the helm—there was nothing that particularly distinguished the Oswald cartoons. It was a successful series without necessarily being innovative. Felix the Cat remained the popular favorite, but there was still room for competition, and Oswald was very well animated for its time and the gags were appealing to moviegoers.

At this juncture, the recent rights jockeying to Oswald continued. Harman and Ising tried to outflank Mintz just as he had done to Disney, proposing to the distributor that they should produce Oswald during the next round of contracts. However, Harman and Ising failed to calculate that the on-going struggle over Oswald Rabbit was starting to embarrass the ultimate rights-holder, Universal Pictures.

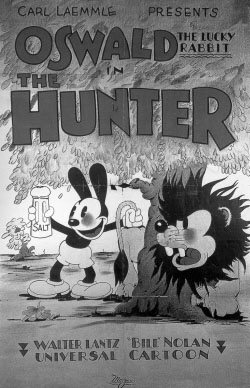

As they agitated to win the deal, it clearly exposed the presence of middlemen in the making of this series. Universal studio boss Carl Laemmle let the Mintz-Winkler contract lapse, rebuffed Harman and Ising, and resolved to have Oswald produced cheaper on the studio lot, ending the distraction of subcontracting the series.

The role of Walter Lantz as counsel to Carl Laemmle in this decision is fascinating to speculate. Lantz had come to Los Angeles a year earlier at the urging of his friend, Bob Vignola. With Vignola’s generosity in hosting him, and bolstered by having a supply of money he had made at the Bray studio in New York City, Lantz was able to settle into a leisurely pace in which to find opportunities in Los Angeles.

The role of Walter Lantz as counsel to Carl Laemmle in this decision is fascinating to speculate. Lantz had come to Los Angeles a year earlier at the urging of his friend, Bob Vignola. With Vignola’s generosity in hosting him, and bolstered by having a supply of money he had made at the Bray studio in New York City, Lantz was able to settle into a leisurely pace in which to find opportunities in Los Angeles.

Furthermore, Vignola was a genuine Hollywood player and introduced him to a lifestyle of casual acquaintance with movie stars and studio heads. Lantz frequented parties and even worked without pay as a gagman at the Mack Sennett studio to gain experience. A watershed event was his active part in driving producer Sam van Ronkel to a weekly high-stakes poker game. Lantz did not play, but he socialized with the producers there, among them Carl Laemmle.

Walter Lantz loved to recount this story by portraying himself as an innocent in Hollywood with the naïve good fortune of having the Oswald series fall into his lap by chance—right place, right time—but surely Lantz was ambitious and savvy enough to see the personal value of using this opportunity well.

Lantz, employed by Winkler on the Oswald cartoons, could even be perceived as something of an informant, given his opportunity to speak directly to Carl Laemmle once a week at this poker game. This would have afforded him the ability to color Laemmle’s judgment of the Oswald contract with Charles Mintz. One can easily imagine that Laemmle’s impression of expenses and ground-floor production on the Oswald shorts, if it was suggested by Lantz, would not have been the sort of access that Mintz or Winkler would wish an employee to provide, however casually, to a big client like the owner of Universal Pictures.

Despite the fact that Winkler’s contract was not renewed, there are not known accounts of him feeling betrayed the way that Disney felt about Mintz. Walter Lantz, throughout his career, maintained the respect of his peers and subordinates, and was considered a very considerate employer. In this case, as in others, Lantz used his salesmanship and geniality to his advantage.

Some of his well-connected friends suggested to Laemmle that Lantz had an impressive resumé of his own, as a former animation director in New York. Most likely, Lantz clinched the job by promising that the Oswald series could be made cheaper by producing it at Universal, and he had real experience with limited budgets, reliably turning out films at Bray for $1900.

Some of his well-connected friends suggested to Laemmle that Lantz had an impressive resumé of his own, as a former animation director in New York. Most likely, Lantz clinched the job by promising that the Oswald series could be made cheaper by producing it at Universal, and he had real experience with limited budgets, reliably turning out films at Bray for $1900.

He accepted a salaried position as head of the new Universal Cartoon Department. Since no animation staff existed, he needed to build it from scratch. George Winkler, operating from his studio on the corner of Western and Virginia Avenue, was obligated to finish the contracted run of Oswalds, even though he was aware that there was no renewal for 1929.

Lantz began contacting Winkler’s staff, offering them positions at Universal, and Manuel Moreno estimated that “one-third or one-quarter” of Winkler employees went to work for Lantz when production shifted to Universal City. Disney and Lantz both needed to quickly build up their studio operations, with each catching trains to New York City to recruit experienced animators. They were vigorously competing against each other, but it was a gentleman’s game.

Despite stories that Disney held grudges, he held none against his professional rival Lantz, even as they criss-crossed Manhattan trying to sign the same prospective employees. Disney was gracious when he heard that Lantz had taken over producing Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. The two Walts met up and had drinks together in New York, a moment of celebration just before the Wall Street Crash of 1929 would plunge the country into the Great Depression.

As it turned out, Walter Lantz played his cards well and had gotten Lucky. In fact, the many contracts that both Walt and Walter extended to animators in New York must have soon been seen as lifelines to a better life in sunny California. And the good fortune to produce the Oswald series for most of the next decade had quite literally been won by Lantz at a weekly poker game.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom-

I’ve been looking for the source of that “Mickey greeting ticked-off Oswald” sketch for a while! Tanks for showing us where it came from.

Fascinating. I’d never read the whole Oswald story in such detail. Thanks!

Walt getting along with the guy who stuck it to Charles Mintz and George Winkler isn’t a surprise when you think about it — He probably appreciated Lantz doing to them what they had done to Disney.

That pen and ink sketch of Mickey Mouse and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit on an off-white 7 x 9 sheet of parchment-type paper was presented to Universal Studios founder Carl Laemmle on the 20th anniversary of the building of Universal Studios. It was drawn and signed by Hank Porter (who was one of the artists authorized to sign Walt’s name). The Oswald figure is inked or traced off an animation drawing from the cartoon Rival Romeos (1928). I BELIEVE Mark Kausler has the original animation drawing and there is a rough Mickey drawing on it as well so Porter may have used it as his rough layout. Didier Ghez posted my copy of the drawing on his blog December 6, 2007.

Jim, thanks for the details and the attribution on that.

Also, to respond to J.Lee and to Evan (“ticked-off Oswald”), it’s really interesting to speculate on those points, and I agree: 1) that Disney might have viewed Lantz favorably for delivering some karmic retribution on the guys who wronged him, surely enough to merit the camaraderie of shared drinks in NYC, among other reasons, and 2) that Hank Porter’s drawing intrigues me NOT because it’s a frame from the aptly titled “RIVAL Romeos” but because in drawing it on behalf of Walt, as a gift to Laemmle in ’35, there remains enough simmering pride and gloating from the Disney Studio to depict Universal’s Oswald as angry at the sight of the approaching Mickey. Surely it was seen as a generous token when received by Carl Laemmle, but it’s a guilty pleasure now to read between the lines and wonder if there wasn’t some small vindictive delight for Walt to approve this drawing, assured that his overwhelming success had seven years later settled that score– leaving Oswald, nearly vanquished, as the one who shows his dismay.

Lantz had a drink with Walt Disney to see if this situation would cause Walt any concern. Walt, who was now successful with Mickey Mouse, gave Lantz his blessing and told him there would be no hard feelings. They remained friendly for the rest of their lives. They often received mail addressed to the other Walt and would forward those letters to each other.

“An old timer in the business slipped in before they [Walt’s former animators] could put over their fast move and took charge of the Rabbit,” Walt told his daughter Diane Disney Miller during the summer of 1956. “I was cheering for him throughout all of that infighting, and I got a kick out of it when he outsmarted the artists who’d deserted me.”

Laemmle was forced out of Universal in 1936, Lantz was clever enough to see that Universal would probably eliminate the cartoon studio so he renegotiated his contract.

He became an independent producer supplying Universal with animated shorts and that the copyrights and trademarks for all of the characters he had worked on including Pooch the Pup and Oswald the Rabbit would belong to him.

I am sure that Walt was not fond of Laemmle because when he had his first meeting with Charles Mintz and found out Mintz was going to set up his own studio, Walt went to executives at Universal to plead his case but they went with Mintz because they felt he was older and knew the business….and had promised to bring in the cartoons for the same or less money using Walt’s own staff.

During the teens and twenties, Universal had released short subjects (comedies, cartoons, newsreels, westerns and others) that were both produced independently and directly by Universal. In 1929, Universal eliminated most of their independent shorts producers. Thus, Hearst International moved to MGM, replaced by the Universal Newsreel, and the Stern Brothers – Carl Laemmle’s brothers-in-law, no less – who had produced comedies independently for Universal from about the beginning of the company, lost their contract and two reel comedy production was taken in-house. I think that the Mintz-Winkler-Harman-Ising-Lantz-Universal fandango mainly resulted from a restructuring of how Universal obtained their shorts.