Last weekend, the actress Lupita Tovar passed away at the age of 106, more than eighty years removed from her starring role as the female lead in Drácula. This distinction had made her one of the last surviving links to the early days of Universal Pictures, when its founder Carl Laemmle oversaw the transition to the new era of talkies. Universal was then earning a reputation for its horror movies and the worldwide success of Phantom of the Opera in 1925 only added to its growing association with Victorian monsters.

Universal had an inadvertent role, though an inciting one, in the birth of sound cartoons. Through the actions of independent producer Charles Mintz, to whom the studio had given a contract, Walt Disney was dismissed from the Oswald series just prior to the revolution he helped to unleash with Steamboat Willie. After that, Universal was quite slow to respond, trying some half-measures to keep up with its more technically savvy competitors.

The public clamor for talkies obsoleted silent cinema and Universal tried to sweeten its recent hits with something called “international sound versions.” These were post-synchronized with music and sound effects. An example was a 1930 re-release of Phantom of the Opera that did not include any spoken dialogue, but instead had music that played over the intertitles. This was sort of a ‘trick’ approach that would not appease the masses for long. As sound films pushed into foreign markets, the regional audiences wanted to hear film actors speak just like they did.

In a sense, the jig was up. The studio had to respond with versions that had dialogue in those languages. And mind you, the art of dubbing had not yet taken hold. So, on October 10, 1930, filming began on a movie that perfectly illustrated a short-lived Hollywood solution. In most ways, it was exactly the same movie as the classic Dracula starring Bela Lugosi with his sweeping cape and leering glare. However, this alternate version had a Spanish-speaking cast and was titled Drácula. It made use of the same sets and a translated shooting script.

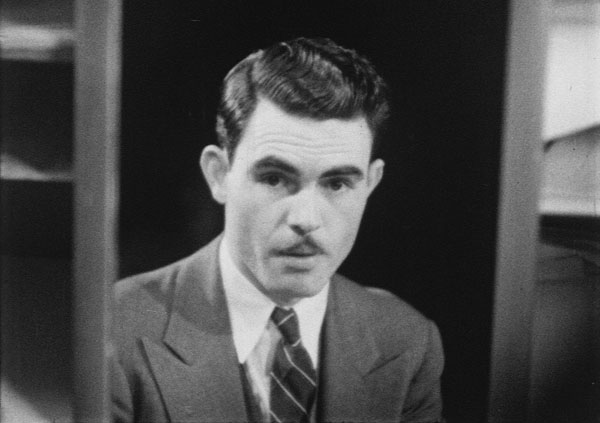

The role played by Helen Chandler was performed instead by Tovar, who was recently signed on contract from Mexico to be a “Universal player.” In fact, the entire Spanish version of Dracula was shot at night, 7pm to 7am, after the English-speaking cast and crew were finished with a day’s work. They did not cross paths, working on opposite shifts. Tovar said she never once even met Lugosi. All of her scenes were filmed with a caped Carlos Villarías as the famous blood-sucking Count.The existence of this nearly shot-for-shot counterpart, a sort of movie doppelgänger, has spawned a fairly lively internet debate about which is better, with a lot of momentum pressing toward the lesser known “Spanish Dracula” on account of a crew that, it is rumored, was competing to make a superior version at night. A century later with side-by-side comparisons online, the debate has hit high gear, but the famous performance of the undead Lugosi does not lie down easily and so the argument continues.

Regardless of which version is better, a certain respect arises from knowing that the Spanish-language shooting schedule enforced a vampire lifestyle on all its cast and crew. There is a ‘Method acting’ purity to this version: everyone involved slept during the day and then went to work at night. Just knowing that makes it seem intrinsically more authentic. Here is an edited clip from Drácula, released in 1931:

Perhaps less well known is that Walter Lantz, who inherited the responsibility for producing the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons, might also have been up late some of those nights while Conde Drácula, played by Villarías, was readying for his closeup on the legendary Stage 28 at Universal. This revelation comes to us from a 1978 interview with Manuel Moreno, in which he disclosed that the Oswald production schedules were so challenging to maintain that Lantz would work at night even after a tough day at the studio.

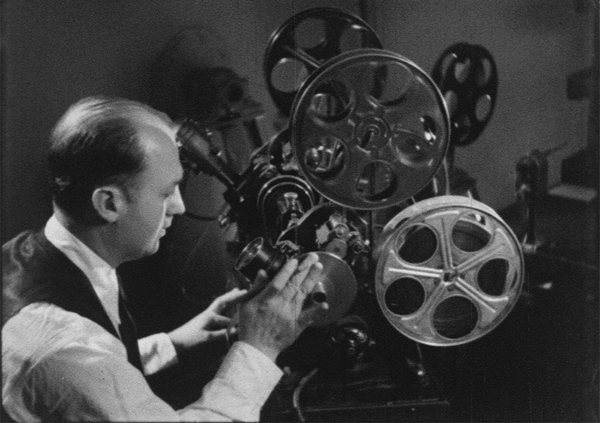

“Lantz used to come at night, and he’d stay there all day Saturday,” said Moreno. It is easy to get the impression that Walter, lacking a precise production discipline, may have brought the cartoons across the finish line by fusing the elements together himself, working alone in the editing room. Considering how loose and improvised we know these early Universal cartoons were—recollections exist of animators stating how nonspecific their scene directions could be—it would make sense that Lantz used the quiet of his nighttime work to assemble his vision from among the individual parts.

Manuel Moreno, a leading animator at Universal, seen here reflected in a mirror at his desk.

In a way, the knock on Lantz has always been that he delegated creative vision for his cartoons to his directors for most of his career. However, the situation would have been different in a year like 1930, when he was a new producer charged with keeping Oswald relevant in light of innovative new sound cartoons coming from Disney. The technical challenge was paramount and Lantz had actually proven himself quite a whiz with hybrid cinema techniques on his prior Dinky Doodle films for Bray, so he was versatile and up for the task.

In 1930 he was still actively a director in addition to being a producer. He was young and hungry and he was the force moving the Universal Cartoon Dept. into the sound era. However, Lantz was not hard-charging and uncompromising like Disney, so maybe some of the magic of his process only manifested as something special if he could bring it all together with the final edit and post-synch. The orderly sophistication of the Disney method was challenged at Universal by a more slapdash approach. And because of the tight budgets Lantz was given, his pragmatism was always a factor in the making of his cartoons.

In 1930 he was still actively a director in addition to being a producer. He was young and hungry and he was the force moving the Universal Cartoon Dept. into the sound era. However, Lantz was not hard-charging and uncompromising like Disney, so maybe some of the magic of his process only manifested as something special if he could bring it all together with the final edit and post-synch. The orderly sophistication of the Disney method was challenged at Universal by a more slapdash approach. And because of the tight budgets Lantz was given, his pragmatism was always a factor in the making of his cartoons.

Bill Nolan was the other producer-director working alongside him, but Nolan was chiefly there for his prodigious ‘pencil mileage’—as one of the fastest animators in the industry—and not necessarily for his management skills. Eventually, as Lantz became the undisputed boss, Nolan moved on and Moreno unofficially became the manager of the animation staff, basically a surrogate who was taking on directing responsibilities. According to Moreno:

“The sound recording was always supervised by Lantz. I had nothing to do with the recording because I couldn’t afford the time, and there wasn’t much that I could do, with Lantz there as supervisor. He knew exactly what the story was about, because he had been with it all through its construction. And the sound effects were no problem: a lot of times [story man] Vic McLeod would record the sound effects or [Pinto] Colvig would… Lantz did all the editing and patching the sound together, synchronizing the tracks”.

It seems that Lantz developed a business practice of being involved in the initial story meetings and then supervising the recording sessions at the end. For the middle of the process he appeared to be mostly hands-off. There were no “sweatbox” reviews of the pencil animation to ensure quality and continuity, as with Disney. That would have been too costly and, in any case, Moreno felt that “we were practically always behind schedule.” The animators really only had one shot at any sequence.

Lantz felt the stress of his situation, especially because his Universal budgets decreased year to year, but he was remarkably easygoing in spite of it and he negotiated the setbacks quite capably, keeping Oswald in production for nearly a decade. It is interesting to think of Lantz returning to Universal at night, editing and completing the cartoons. Lantz was technically adept and perhaps he liked the solace of quietly working alone without distractions.

Walter Lantz at the Movieola

I suspect he developed this nocturnal habit by 1930, growing his proficiency with the finer art of comedic synch-sound. Since this was a paradigm shift that shook the industry, failure to adapt was not an option. Musical director Jimmie Dietrich helped him with this process during regular hours, but it may have been at night that Lantz honed his craft, running the strips of film elements back and forth. Although Lupita Tovar never met Bela Lugosi, it is possible she crossed paths with Lantz. It is fun to speculate about such a thing, though we will never know.

A connection we do know is that Manuel Moreno and his brother George were amateur film enthusiasts and, during the early 1930s, they shot a home movie of the Universal animators clowning around on Stage 28, the legendary ‘Phantom of the Opera’ set that was repurposed for many classic monster movies. Judging from a copy of this home movie that I own, “The Gang at Universal” — as they are referred to on the title card — had a blast using the opera house façade for their filmed gags.

As an animated homage to this famous stage of horror, the 1930 Lantz cartoon Spooks is an outright spoof of Phantom of the Opera, possibly even made to be shown in front of the featured “international sound version” released that same year. Oswald meets the phantom in the cartoon and then vanquishes him by answering a riddle (“Ouch!”) that was the punchline to a popular American joke at the time. Enjoy watching this cartoon. And imagine Walter Lantz working the vampire shift.

Manuel Moreno was interviewed by Milton Gray in January 1978, in Santa Ana, California. Excerpts above are from this interview, a copy of which exists in the Manuel Moreno collection archived at Stanford University. The frames of Walter Lantz and Manuel Moreno are taken from a “Going Places with Lowell Thomas” short titled Cartoonland Mysteries (1936) from an HD transfer by Steve Stanchfield. For the top image, I stitched together Bela Lugosi and Lupita Tovar, day for night, forever linked and yet never to have met.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Did I see a Mickey Mouse clone in that ‘Spooks cartoon?

I’m pretty sure every studio other than Disney at that time had their own Mickey Mouse cameos.

Your information about the 1930 Phantom of the Opera isn’t quite accurate. It wasn’t just the 1925 original with a music-and-sound-effects score tacked on. The 1930 version of the film did feature spoken dialogue. It was, in fact, a hybrid, with almost half the movie remade with sound, and the remainder, including all of Lon Chaney’s scenes, recycled from the silent original. While the soundtrack exists, the picture element for this “part-talkie” version is lost. What does survive of the 1930 Phantom is a silent version prepared for release to theaters who were not yet wired for sound. (There’s something very ironic about a silent version of a part-talking remake of a silent movie.)

Part-talking films were disappearing by this time, but had been quite common in the late ’20s. Take a silent film, throw in a scene or two that featured the actors speaking, and you could advertise your picture as being a “talkie.” In fact, that’s what The Jazz Singer is: a silent film with some scenes written in for Al Jolson to speak (and sing). So audiences, having seen these types of films for two or three years by the time the 1930 Phantom showed up, would have been accustomed to movies that moved back and forth between talkie scenes with spoken dialogue and silent scenes with title cards.

Jon, I really appreciate you clarifying those aspects of the 1930 versions of Phantom, even more hybrid and variant than I fully realized, and how true: what an irony that there’s only a surviving silent of the part-talkie, and also a filmless soundtrack. I guess makes it even more fitting now that my selected clip from Drácula includes some contemporary ensemble scoring: a remix of a doppelgänger of classic cinema, still shifting in form.

I did a double take when I saw the picture at the top with both Lugosi and Lupita Tovar! An elegantly whimsical photo from a DRACULA that never was…

Gene, I’ve noticed that same comment on the YouTube site, people remarking on the appearance of that Mickey clone within “Spooks.” It was not an uncommon sight at the time to see the familiar geometry of those mouse ears in various cartoons, but more striking now to see it within an Oswald, I suppose. In fact, such mice clones even pre-date Mickey himself. And to B. Baker, glad you liked the Lugosi-Lupita composite pic, my tribute to Ms. Tovar.

A lovely look back at the early days of “talkies,” with all their opportunities and uncertainties. It’s interesting in “Cartoonland Mysteries” to see Walter Lantz adeptly operating a film splicer in which many of the operations, like the cutting blades and cement clamps, are controlled by foot pedals.

I thought that the Spanish DRACULA was only a little bit better than the English language Lugosi one. The lighting isn’t as good in the Spanish one, so it doesn’t have the grey scale of the Lugosi film(my anal point of the day).