A lonely tuba’s storied rise from one low-budget record to a star-studded history of award-winning fame and game-changing entertainment.

Tubby the Tuba may be the most historically significant children’s recording ever made. The first version was inducted into the Library of Congress National Sound Registry. The George Pal short film version was nominated for an Academy Award. The José Ferrer recording was a Grammy landmark. And the 1975 animated feature was the unexpected genesis of the studio that changed the contemporary animation industry.

The creation of Tubby the Tuba began almost exactly eighty years ago with a writer/actor named Paul Tripp. Dick Van Dyke Show fans might know him as one of the boyfriends of Sally Rogers (Rose Marie). Kids of the late fifties and early sixties watched him host the CBS children’s series On the Carousel, Let’s Take a Trip and Mr. I. Magination (a Peabody Award winner featuring Tripp’s wife, Ruth Enders, and the “fresh-faced” Walter Matthau and Richard Boone). New York kids knew him as the Birthday House co-host with another children’s entertainer of the era, Kay Lande (and many listened to records based on these shows).

Paul Tripp wrote and costarred in the 1966 U.S.-Italian feature film The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t, based on a Mr. I Magination storyline. Directed by and co-starring Rossano Brazzi with another New York TV host, Sonny Fox, it was the first original feature released by Childhood Productions, a company founded by former United Artists executive Barry Yellen that specialized in redubbing West German fairy tale films. Also in 1966, Childhood Productions released Gene Deitch’s compilation feature, Alice of Wonderland in Paris. Yellen provides a fascinating account of his company and the making of the Christmas film here.

Paul Tripp wrote and costarred in the 1966 U.S.-Italian feature film The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t, based on a Mr. I Magination storyline. Directed by and co-starring Rossano Brazzi with another New York TV host, Sonny Fox, it was the first original feature released by Childhood Productions, a company founded by former United Artists executive Barry Yellen that specialized in redubbing West German fairy tale films. Also in 1966, Childhood Productions released Gene Deitch’s compilation feature, Alice of Wonderland in Paris. Yellen provides a fascinating account of his company and the making of the Christmas film here.

Kleinsinger met Paul Tripp when the latter appeared in the former’s opera. In Kleinsinger’s liner notes for the Peter Pan Records version (narrated by radio personality Johnny Andrews), he recalls the original of the story:

“Tubby came out of a real-life happening. While attending a rehearsal of a work of mine performed by the NBC Symphony, a sad and curious event occurred. The conductor, Milton Katims, kept admonishing the tuba to play his oompahs softer, time after time. You see, it was summer, and some of the basses were on vacation; so this tuba (Herbert Jenkel) was endeavoring to fill in for the missing bass players. Eventually, the tuba was asked not to play at all. No one disputed that Mr. Jenkel is a great tubist, but it was Mozart they were playing, and the oompahs were a bit heavy.

“After rehearsal was over, the frustrated tuba came over and asked me, very plaintively, whether I would consider writing a concerto for solo tuba and orchestra. Sitting with me was my friend, the writer, Paul Tripp. We were both struck by the comic-tragic aspects of the request—the poor instrument wanted his solo melody to play, Thus, “Tubby the Tuba” was born—and for a happier ending still, the man hired to play the first recording of “Tubby” was that same frustrated tuba player.”

“After rehearsal was over, the frustrated tuba came over and asked me, very plaintively, whether I would consider writing a concerto for solo tuba and orchestra. Sitting with me was my friend, the writer, Paul Tripp. We were both struck by the comic-tragic aspects of the request—the poor instrument wanted his solo melody to play, Thus, “Tubby the Tuba” was born—and for a happier ending still, the man hired to play the first recording of “Tubby” was that same frustrated tuba player.”

In 1941, a week after Pearl Harbor, Tripp began writing what would become Tubby the Tuba, according to his son, David Tripp. He told The Berkshire Register that it was finished in only two weeks, then friends and family continued to work on getting the song recorded while his father was overseas.

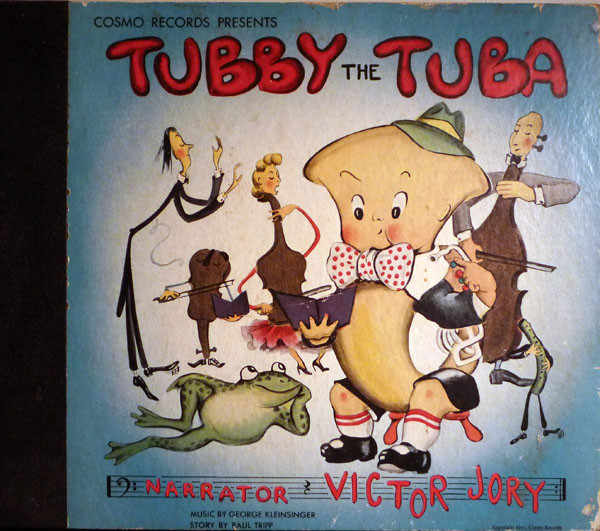

“Widespread success for “Tubby” had an equally long gestational period,” wrote Cary O’Dell in this article on the Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board site. “Tripp would relate later, ‘For years, nobody wanted it until a little company called Cosmo Records [a subsidiary of Cosmopolitan magazine] put it out. It was Walter Winchell who discovered it, wrote about it in his column, and turned it into a big hit.’ The original ‘Tubby’ (the one named to the National Sound Registry in 2006) was issued in 1945 as a two-record 78rpm set. Its multi-color cover was charming, depicting all the story’s main characters including a bow-tied Tubby. Printed on the inner album sleeves was Tubby’s full story, complete with a handful of simple line drawings illustrating Tubby’s early malaise, his sojourn into the forest and his orchestral return.

The very first recording was performed by character actor Victor Jory, a “you’d know him if you saw him” character actor seen in countless movies such as The Miracle Worker and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as well as the star of the movie serial The Shadow (based on the pulp magazines) and TV shows like Mannix (on which he played Mike Connors’ father).

It is also Victor Jory who narrates the Academy Award-nominated version of Tubby by George Pal for the final in his series of stop-motion Puppetoons before he moved into live action films. It most dazzlingly presented on the first Puppetoon Movie Blu-ray (and speaking of Puppetoons, don’t forget the super second volume with the Bugs cameo!).

Original Puppetoon production figures. Tubby is made of gold painted plaster and sits alongside his friend the bull frog, who is made of plastic. (Smithsonian National Museum of American History Behring Center Collection)

Released by Paramount in 1947 and designed by Reginald Massie, Pal’s version of Tubby brought Victor Jory back to re-record his narration for the soundtrack. Clarence Wheeler, who did scored so many cartoons for Pal’s pal Walter Lantz, was the musical director.

In another animation connection, George Kleinsinger also composed the music (with lyrics by Man of LaMancha’s Joe Darion) for the musical version of Don Marquis’ Archy and Mehitabel, a series of newspaper verse stories (many illustrated by Krazy Kat creator George Herriman). It was an album in the early fifties, a stage show in 1957, then a live 1960 TV broadcast. Along the way, additional material was contributed by Mel Brooks and it was retitled Shinbone Alley. John Wilson directed the animated feature version released in 1971.

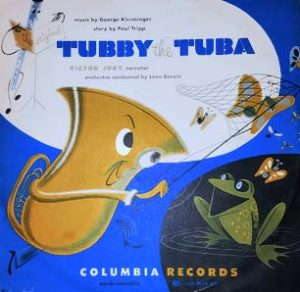

Judy Gail Krasnow shared vivid childhood memories of George Kleinsinger in her book, Rudolph, Frosty, and Captain Kangaroo: The Musical Life of Hecky Krasnow Producer of the World’s Most Beloved Children’s Songs. She was a young girl when her father produced Tubby the Tuba for Columbia Records with Tripp as narrator to great success. She wrote:

“Kleinsinger lived in the Chelsea Hotel… where he could transform his abode into a lush jungle. His precious grand piano stood in amidst tanks of tropical fish, including an aquarium of piranhas. In the corner, a waterfall, flowed and splashed, while free-flying birds roosted wherever they desired…

“George Kleinsinger was an odd but sociable man, and his apartment was a melting pot for all kinds of characters from the respectable, conservative, conformist, and reputable to the offbeat, liberal, eccentric and disreputable. His array of animals included pythons, mice, insects, birds, an ocelot, a ferret, and of course, monkeys. He fancied himself Father Nature… He created a mini-Amazon rain forest in the living room, parlor and den. Only the kitchen and bedroom had standard furniture. The jungle rooms were adorned with seats that looked like logs, and the living room had one big couch and chair upholstered with fabric of a jungle motif.”

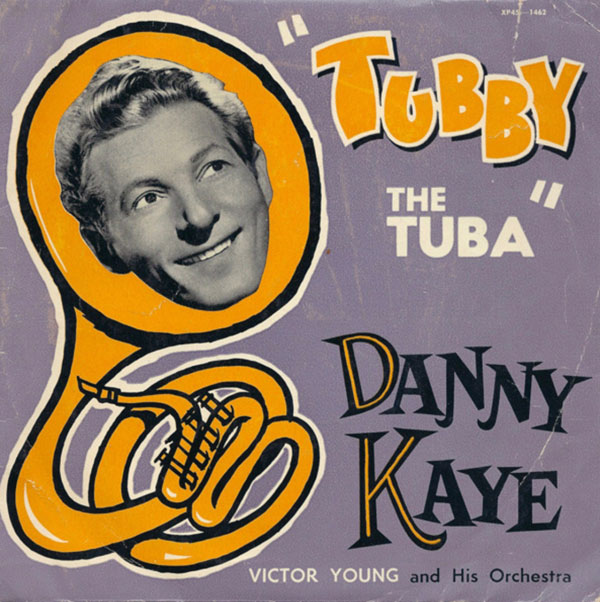

Danny Kaye and Decca Records executive Dave Kapp at the recording session for Tubby the Tuba. (Kaye/Fine Collection, Library of Congress)

Fifty years later, The Manhattan Transfer vocal group paid tribute to Kaye’s disc with a letter-perfect re-creation in stereo, along with other musical Tubby stories on their only children’s album. Broadway stage actor/director José Ferrer’s performance of Tubby the Tuba for MGM Records earned the first Grammy Award for Best Children’s Recording at the first Grammy Awards ceremony in 1958.

Another best-selling version was recorded by Disney Legend Annette Funicello was released in October, 1963. It was her last Disneyland children’s album, as she transitioned from Disney movies to American-International movies; a few months after the release of Beach Party (the first in the series) and before The Misadventures of Merlin Jones.

This irreplaceable gem was dished up by TV chef Julia Child with the Boston Pops, which was released on records as well as broadcast on PBS.

Tubby the Tuba was also written as a children’s song. While not recorded as often as the story version, it received the celebrity treatment several times. This version from Cricket Records (and reissued on Happy Time was arranged by Rankin/Bass composer/conductor Maury Laws.

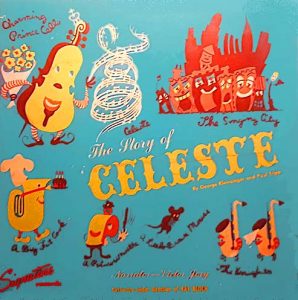

Peter Pan Records’ aforementioned Tubby LP was backed with the exquisite “Toy Box Suite,” a collection of the works of Kleinsinger with Tripp, including narration-clear renditions of Tubby Theme and the haunting melody from The Story of Celeste.

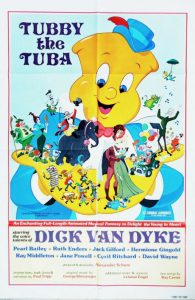

In 1975, a curious feature-length animation production was released. It was only the second animated Tubby the Tuba, but this time using hand-drawn animation. Even though the results were a undeniable misfire, in the long run it was not for naught.

“The origin of Pixar goes back to Alexander Schure, an entrepreneur and founder of the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT). Schure was a fan of animation and in the 1970s he used his money and resources to make an animated film that he wanted to rival Disney,” wrote Eli Sanza on ejunkieblog,com. (Sanza’s account of the story is succinct and comprehensive, but not the sole account in existence.)

Schure had spectacular facilities and vast financing, but no knowledge or patience with the tedium of cel animation. But he did have vision. “He recruited consultants from NYIT who knew how to use computers to see if they could make Tubby the Tuba computer-animated instead,” wrote Sanza.

A cel set-up from TUBBY THE TUBA (1975)

But it was too early technically to tackle a CGI feature film in the early seventies. Instead, a team of new and veteran animators created a film that makes all manner of missteps. One of the animation veterans involved in the feature was Sam Singer, and the characters resemble some of his cartoons.

The film divides Tripp’s original Tubby story in two. The second half does not occur until the end. Between this enormous gorge are adaptations of the recordings Tubby the Tuba at the Circus and The Story of Celeste with much more dialogue and expanded songs. By seventies TV animation standards, the beginning and end could have been joined into a half-hour special and considered charming, especially with Cyril Ritchard’s amusing performance as the Frog (his last film credit).

The voice cast includes Dick Van Dyke as the voice of Tubby, with Ritchard, Pearl Bailey, Hermione Gingold and David Wayne (who recorded a Tubby album for Cricket Records and the first Archy and Mehitabel album).

The voice cast includes Dick Van Dyke as the voice of Tubby, with Ritchard, Pearl Bailey, Hermione Gingold and David Wayne (who recorded a Tubby album for Cricket Records and the first Archy and Mehitabel album).

What is most historically significant about 1975’s animated Tubby the Tuba for today’s industry was the feature that was attempted and researched but not made. Had this project never happened, things might have been different.

“The consultants for the non-existent CG version of the movie had stayed together at NYIT at the Computer Graphics Lab, its four original members being Edwin Catmull, Alvy Ray Smith, Malcolm Blanchard and David DiFrancisco. Schure kept the lab financed, but the tech people there had ambitions to work at actual film studios,” wrote Sanza. ‘Luckily people like Star Wars director George Lucas saw the potential of computer animation as a tool for future filmmaking, and Lucas offered the tech guys at NYIT jobs at Lucasfilm.”

In 1979, Catmull headed the Computer Graphics Lab at ILM, where Smith was leading the Graphics Group of ILM (Industrial Light and in 1979. By 1986, the Graphics Group became Pixar.

Dick Van Dyke may have either forgotten (or chose to forget) his sole lead role in an animated feature, but it does add a fascinating footnote to his already phenomenal career–just part of the epic journey of a plaintive tuba, whose first recording wasn’t heard by its own author for years until after the end World War II. “My father returned from China,” recalled Paul Tripp’s son, David. “And on Christmas Eve, Dec. 24, 1945, my father heard Tubby the Tuba for the first time, recorded with a full orchestra. It was as I got older that I realized in many ways, my father was a hero.”

“Three Adventures in Music” Narrated by Paul Tripp

George Kleinsinger’s original arrangements were used for his compositions on this early Golden LP version of Tubby the Tuba, Adventures of a Zoo and The Story of Celeste (below), all narrated by the author, Paul Tripp. Golden Records received screen credit for their soundtracks of such Tripp-narrated Childhood Productions theatrical features as The Bremen Town Musicians, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

Again, your usual outstanding work with amazing research. Tubby the Tuba was an emotional childhood favorite of mine but I never realized how extensive his history was. Thank you for all your columns and in particular this one that brought back many fond memories listening to it with my parents.

Thanks, Jim! Tubby and I are kindred spirits. No matter which record I listen to, when the music gets to “and they ALL played!”, it still gets to me.

These accounts of Tubby’s origin simply don’t add up. If Tripp wrote the story in the weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor, then it could not possibly have been inspired by the events recounted by Kleinsinger in the Peter Pan liner notes.

Herbert Jenkel joined the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1943, replacing its original tubist William Bell, who had taken a position with the New York Philharmonic. Also in 1943, Milton Katims was hired for the first desk of the viola section to replace William Primrose, who had left to embark on a solo career. Conductor Arturo Toscanini, for whom NBC president David Sarnoff established the orchestra in 1937, quit in 1941 over a contract dispute and did not return until 1944 (though he did conduct the orchestra in fundraising concerts to benefit the war effort, for which he received no pay). Leopold Stokowski assumed the directorship in the interim. It was not until after Toscanini’s return that Katims was appointed assistant conductor, a post he would hold until the orchestra was disbanded in 1954. So any rehearsal conducted by Katims could only have taken place in 1944 at the very earliest. (Milton Katims, later Artistic Director of the Seattle Symphony for many years, is a very well-known figure among violists, and one of my viola teachers was a colleague of his in the NBC Symphony Orchestra.)

Kleinsinger’s remark that “it was summer, and some of the basses were on vacation” is also spurious. First-tier professional orchestras normally have six to ten weeks off in a year, and it is then, and at no other time, that the musicians are able to go on vacation. Back in the forties, any orchestral musician who tried to take time off for a holiday in the middle of the concert season would have been replaced quicker than you can say “molto prestissimo”.

And whatever the orchestra was supposedly rehearsing, it couldn’t have been Mozart, because he never composed anything for the tuba. Mozart died in 1791, and the tuba was only incorporated into the symphony orchestra in the 1830s with the symphonies of Hector Berlioz. Even then, it wasn’t a modern tuba but an instrument called the ophicleide, which had keys like a saxophone instead of rotary or piston valves (ophicleide means “keyed serpent”). It looked sort of like a brass bassoon with a flared bell.

In 1925 Ernest La Prade wrote a children’s novel titled ALICE IN ORCHESTRALIA, in which a little girl named Alice falls asleep at an orchestra concert and travels down the bell of the tuba (just as another Alice went down the rabbit hole) to a land of living musical instruments. It was heavily promoted by musical societies, and by 1940 it had been adapted into a radio serial and a children’s record album. So there was already recent precedent for a children’s story with musical instruments as characters, hence evidence of a market for such stories. I suspect that Kleinsinger’s account was concocted after the fact. There may be a grain of truth in it — at least he bothered to drop the names of real people — but only a grain.

Be that as it may, “Tubby the Tuba” has endured while LaPrade’s novel has faded into obscurity, and there have been other works written in the same vein. A violinist in the Detroit Symphony named Harold Laudenslager was a composer as well, and after he died his widow spent a lot of money having his music professionally transcribed and arranging for its performance. One work was a children’s piece for narrator, orchestra, and a solo instrument that never gets to play a melody, in this case the timpani. Its title, which to this day I cannot say out loud without laughing, was “Ho Ho Hum, the Lazy Kettledrum”. I was in the orchestra at its premiere, but the conductor thought it was so ridiculous that he eliminated the narration and billed it on the program under the generic title “Concerto for Timpani and Orchestra”. I never met Laudenslager and don’t know for certain whether it was Tubby that inspired him, but everyone in the orchestra thought so.

Paul — thanks as always for taking so much time for such detailed history. To clarify, I assume your statement of the story of Tubby’s origin not adding up refers to Kleinsinger’s Peter Pan liner notes than to anything else in the article, and am sure your account is accurate.

We’ve seen countless examples of how time and perception can play “Rashomon”-like games with recollections, especially when connected to works of great renown. Keith Scott wrote an excellent 2016 CR article, just as an example, on Mel Blanc that examined similar issues:

https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/mel-blanc-from-anonymity-to-offscreen-superstar-the-advent-of-on-screen-voice-credits/

In some accounts, Tubby The Tuba was acknowledged as being inspired directly by “Peter and the Wolf,” and it is certainly very much like “The Ugly Duckling.” Like westerns, science fiction and other storylines, there are only so many variations on a theme. It’s about transcending what has come before with that certain “something” that resounds with people.

I love “Alice in Orchestralia” and it can be enjoyed here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vy_NrJp7a4s

Always happy to contribute, Greg. I wouldn’t have thought the subject of personnel changes in the NBC Symphony Orchestra would ever come up on Cartoon Research, but in the little world of orchestral musicians, believe me, those guys were legends!

Greg, thanks for the shout out to the Puppetoon Movie Volumes 1 & 2. BTW, I’d also like to point out to everyone that Arnie Leibovit is currently working on Volume 3 on Blu Ray and has a crowdfunder in place for that project on his website (just click on my name). He can sure use your help.

Fond memories of watching Birthday House as well.

The narrator of “The Peter Pan” LP edition of “Tubby The Tuba” was former Cleveland, Ohio and NYC based kids tv actor/storyteller/singer and musician: Johnny Andrews.

Also, two more well known NYC based kids tv hosts/performers narrated Paul and George’s beloved children’s musical story on LP’s: Sonny Fox For “Simon Says” kids records and Chubby Jackson (I don’t recall which label Chubby recorded on – But I do know that an image of the disc’s cover does exist).

Kevin — Coincidentally, Simon Says Records were, at least in part, produced by Cosmo Records, which made the very first Tubby recording. I found a Chubby Jackson recording here:

https://archive.org/details/lp_tubby-the-tuba-goes-to-town_chubby-jackson-harvey-phillips

Chubby Jackson was also the bassist for some of Woody Herman’s finest Herds 🙂 One of his basses resides in the Museum of Making Music in Carlsbad, CA. (Chubby was a longtime resident of San Diego County).

I fondly remember both Paul Tripp on “Birthday House” on WNBC-TV/4 and Sonny Fox on “Wonderama” on WNEW-TV/5. Sonny Fox passed away last year at age 95, ironically from COVID-19.

I remember that we had a Paul Tripp “Birthday House” LP on the Musicor label. The biggest artist on Musicor was Gene Pitney, who shared a birthday with me.

Lots and lots of clever research, Greg! Thanks. I remember listening to a tubby record back in 1955 when I was in kindergarten. I don’t recall the storyline much, but how wonderful that teachers were free to share such entertainment. Thanks, dude!

That’s so very nice of you, Jymn. Thanks!

The very first Tubby the Tuba record I ever heard as a wee babe was the one narrated by Annette and conducted by Camarata. So that’ll always be “the definitive version” in my mind.

I always mixed him up with the tuba prince for the cartoon “Music Land” , but I see now that he is a different character, the ilustration at the beginning of the article looks really cute if somewhat weird with those human-like hands.

There was also another famous series of kid’s records of a little cartoon boy ( perhaps at a piano ) who joins an orchestra of personified instruments… anyone recall these?

Regarding Herbert Jenkel…..He was my godfather. He was a dear friend of my father Paul Zikoll who was a concert bass violist. They were together with the NY Symphony Orchestra underToscanini Herbert later join the LA Philharmonic and lived in Tujunga, CA with his wife Margaret.

Gerda Zikoll Cornell