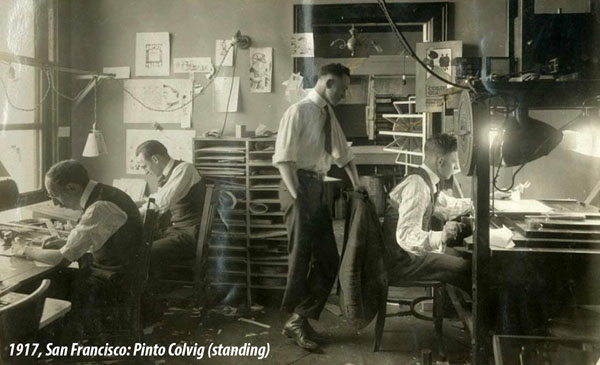

One of the mysteries that even Pinto Colvig’s memoir does not entirely clear up is the length and nature of his employment at Universal Pictures, working for Walter Lantz on the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons. For certain he was a musical talent and a voice artist on the films, as he describes in print, yet judging by the “Artist” credits he receives during the years 1930 and 1931, he likely had been animating, too. This makes sense because Colvig had been working for the better part of a decade as an animator in various capacities.

The narrative trajectory of Colvig’s memoir is that the many roads he had taken prepared him for his ideal job at Disney, with the lion’s share of his book about his humorous vocal work and gagman contributions to the renowned studio during the 1930s. His prior work as a jack-of-all-trades performer makes for some amusing diversions, but generally by the late ‘teens and 1920s he had traded in the extroversion of his rollicking stage acts—a Pantages vaudeville tour beginning in 1913 and two seasons clowning for the Al G. Barnes traveling circus—for the more measured craft of animation.

Although he wrote It’s a Crazy Business in the early 1940s, the manuscript remained unpublished until just over a year ago. I have studied it a bit, and the following passage is curious because of how fleeting Colvig makes his time at Universal: “The day after I worked on the first Looney Tune, I worked for several months on the first series of Oswald sound cartoons.” He also mentions that he “got a release from Universal [to begin at Disney in September 1931]” which suggests he was on a longer term contract with Lantz. Those usually lasted at least a year, and this is also borne out by the duration of his film credits, stretching across two years.

I am not sure why Colvig diminished his involvement with Oswald except to say that perhaps he was hurrying it along to get to the main story of his time at Disney. This is a tendency that I have noticed before, such as years ago when I interviewed Ed Benedict. When I focused my questions on Universal, he remarked to me that no one asked him about those years and he said he rarely spoke of it or even thought of it, a kind of ‘inferiority complex’ applied selectively. Yet those years were surely important to Colvig in terms of setting him up for his leap to Disney, bolstering his résumé and abilities as a performer for sound cartoons.

When Pinto ran his own studio in San Francisco with fellow animator Benjamin “Tack” Knight—they named the business Pin-Tack-O Animated Cartoons—he at least had the stimulating outlet of making promotional appearances and introducing his films. In a 1921 cartoon for the San Francisco Chronicle, drawn by Knight, one has to wonder if there is an in-joke here, with Pinto saying “I git stage fright” entertaining the kids for a regular matinee performance at the Imperial Theater. It seems hard to imagine Colvig thus afflicted. To the contrary, his irrepressible spirit must have required a release from the passivity of drawing those thousands of pictures.

By 1923, he moved his family to Los Angeles to pursue new work in Hollywood. However, his value as an animator led him to continue in his prior line of work, or what Colvig called “trick stuff.” He eventually spent a few years creating visual effects for Mack Sennett’s live–action shorts. These usually took shape by “double-printing” two positives, the filmed footage and the animated overlay, to combine the images on a new negative. Often his work was mundane, directly printing on the film what audio would soon replace: the radiating lines of sounds, sometimes including the words of noises made. Or sometimes it was smells or swarms of bees or expressive indicators.

There were plenty of occasions, though, where Colvig’s animation was intended to serve as the gag itself. In his book, he writes at some length about a swordfish he animated, presumably the fast-moving fish that zips through Billy Bevan’s legs in A Sea Dog’s Tale (1926). For The Pride of Pikeville (1927), he animated wispy characters that materialize from cigarette smoke blown by Baron Bonamo, a nobleman played by comedian Ben Turpin.

At the point where the actual puffs dissipate, Colvig overlaid his animation filmed on reversal to make the lines white. The first image the Baron sees is the alluring face of a woman (a fellow traveler whom he is about to meet) and then his second puff conjures a jackass that sticks its tongue out at him. Colvig never made mention of this sequence, but for a number of reasons I can attribute it to him, especially the style of drawings that matches other work by him. In the bottom right of the frame above, I have composited (and inversed) a cartoon ‘horse’ Colvig drew, as a point of comparison.

The cataloguing of Colvig’s animated work on the Sennett comedies deserves to be done; there are numerous examples to track down. However, the most notable anecdote seems to be from one that got away, a film for which no copy currently exists. This was a feature-length romantic comedy that Mack Sennett himself directed, an epic wartime picture that he hoped would turn the tide on the box-office slump of his once-mighty film empire. In late 1928, The Good-bye Kiss was released by the newly acquired First National subsidiary of Warner Bros. In his memoir, Colvig described this sequence from the film:

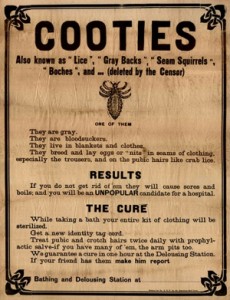

“Sennett had a pet gag he had wanted to do where, in the trenches, Andy Clyde looked out “over the top” through a pair of binoculars. A cootie hopped from his eyebrow onto the lens. This, magnified, appeared to Andy to be an enormous monster. He almost fainted as he breathlessly grabbed the general by the arm and announced that “the enemy is approaching on dragons.” The blustering general smelled of Andy’s breath, grabbed the field glasses away from him, looked through, and saw the same hideous monster. Well, for three months I drew cooties of every description.”

The term cootie had currency then as a term for lice that infested soldiers in the trenches in World War I. Today it survives in North America as a playful term used by kids to describe an imaginary contagion they can pass to friends. One reason this sequence took so long is that Sennett was continually unsatisfied with the results, demanding new versions. As the motion picture ran into problems and the costs mounted, Sennett’s displeasure with the animated cootie became a simmering tension between the two men. This dispute became a classic “you can’t fire me, I quit” sort of moment, and Colvig angrily left the studio.

This is the point where Walter Lantz caught his big break after moving to Hollywood the year before. He was rooming with Frank Capra at the Hollywood Athletic Club, and Capra informed him that Sennett needed someone to finish the sequence. Walter Lantz, very capable with this kind of assignment from his work at Bray in New York, was hired. In fact, he was so proficient that he animated the cootie in just a day by Lantz’s telling. The Colvig memoir says Lantz did it in two days.

This is the point where Walter Lantz caught his big break after moving to Hollywood the year before. He was rooming with Frank Capra at the Hollywood Athletic Club, and Capra informed him that Sennett needed someone to finish the sequence. Walter Lantz, very capable with this kind of assignment from his work at Bray in New York, was hired. In fact, he was so proficient that he animated the cootie in just a day by Lantz’s telling. The Colvig memoir says Lantz did it in two days.

Whether one day or two, Lantz animated the cootie so expeditiously that his new co-workers implored him to delay showing Sennett. It was judged better for the boss to think it had been much harder to pull off. This was the version made it into the theatrical release. Apparently it was well-received and Lantz once described to an L.A. Times reporter (May 17, 1992) that it was only just “a black spot with six legs walking across the screen. The soldiers in the scene took one look at it and over the horizon they went.”

Just a black spot! That he had so easily won Sennett’s blessings and gotten big laughs at movie houses incited Colvig to do some incredulous ‘splaining of Lantz’s approach: “He simply animated a real looking cootie and knocked the job out in about two days, and Sennett thought it was great. I could have done it in two days, myself, but from the start, Sennett had warned me never—NEVER—to draw the exaggerated insect to look like a real cootie—hairy and the like of that.”

From those anecdotes we are left to speculate what this Good-bye Kiss sequence may have looked like. Both men got mileage out of telling this story. The mutual experience of working under Sennett was a bond that they shared. Within the year, the two men were collaborating on their Bolivar the Talking Ostrich film. Then, shortly thereafter, Colvig worked for Lantz at Universal.

It is from one of their Oswald cartoons that we may have the closest surviving thing to their infamous cootie sequence. In fact, knowing the laughs they shared over what Colvig called “my ‘goodbye kiss’ as well,” this gag has the potential to be an in-joke between them. In Kentucky Belles (1931), Oswald’s girlfriend watches him compete in a horse race. As she looks through her binoculars, a bug suddenly slimes the eyepiece. Once she realizes the cause of it, she shoos away the bug and flicks off the excrement.

Their collaboration thus cootied again, Colvig shortly took leave from working with Lantz. He set his sights on Disney. The Mouse got the better of him and he saw it as his professional destiny to make the leap over to where greater opportunities lay. Besides, in his memoir he added that “to expect a raise in salary at Universal at that time was out of the question.” After those few years of sharing a career path—both making Bolivar the Talking Ostrich and then making Oswald sing—their paths diverged.

Unless proven otherwise, The Good-bye Kiss is lost and we can only just do our best to reconstruct what that cootie may have looked like (if anyone knows of a surviving copy of the film, please post a comment below). Until that time, enjoy this cartoon with Oswald racing a horse and a “mickey mouse” riding, yes, an ostrich. You’ll spot the binocular gag around the 2:00 mark. Watching Kentucky Belles remains a fitting way to commemorate the fruitful collaboration between Walter Lantz and Pinto Colvig.

With acknowledgements to the Southern Oregon Historical Society. The quotes above are Pinto Colvig in his own words from his memoir, It’s A Crazy Business: The Goofy Life of a Disney Legend, published by Theme Park Press and edited by Todd James Pierce. Special thanks to Brent Walker and Lea Stans.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

A Cootie was also a plastic toy bug that I had when I was growing up in the 60’s. It had green legs, a yellow body, head that was either pink or red (or might have been black), and antennae. It might have had wings, too, I’m not sure. The parts could be assembled and taken apart easily. That was what I always thought of when people used the word “cooties.”

Here’s a 1924 Mack Sennett Harry Langdon comedy PICKING PEACHES with a couple clever gags involving animation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AWoh-0nTMjE

One has a devil appearing on Harry’s shoulder at around 14:25.Another starting at 21:24 has animated daggers flying out of jealous husband Kewpie Morgan’s eyeballs.

Earlier around 14:34 there’s some tricky animated diving.

Since Pinto was in LA in 1923 these most likely are his animations.

Here’s another Mack Sennett comedy WALL STREET BLUES (1924) check out the animated gags at 3:50 and the winking skull and cross bones on a bottle of poison at 10:55.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLrqftnOB9w

Tack Knight would be an assistant/ghost on Gene Byrnes’ comic strip “Reg’lar Fellers,” and would later launch his own kid strip, “Little Folks.”

Later still, Charles Schulz wanted to call his comic strip “Li’l Folks,” but was stopped by Knight, who wanted to revive “Little Folks” (a title he owned), which hadn’t been in papers in years.

Thanks Pat for the links. Hey, I like the idea of ‘crowd-sourcing’ an inventory of those ol’ animated bits within the silents. And I wanted to mention to all that THE PRIDE OF PIKEVILLE (with Ben Turpin as Baron Bonamo, seen in the smoking image above) is available on a BluRay called The Mack Sennett Collection, Vol. 1. Or you can see the sequence in lower resolution at 6:20 of this video:

https://youtu.be/EfIlYUHsm88

And just after the 7:00 mark you can see photographic effects to create the background passing in the train windows. These type of effects were done by other Sennett staff (in this case K.G. MacLean, based on Pikeville credits) who would have filmed Colvig’s animation, or handled the double-printing, for such bits. Lantz’s preferred method, which he used earlier at Bray, was to have each frame of live-action developed as an 8×10 still over which he then placed a cel of animation to shoot composite images to a negative. I believe the Sennett studio’s double-printing method was different, generally not incorporating cels.

“Yukon Jake”, 1924. Around the 15:30 mark the bear — real in other shots — does an animated flip. Not sure, but on my screen it looks like Turpin might also be animated in that same shot:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zldrjDTyGW8

“Dream House”, 1931. Post-Colvig Sennett short, but note the two shots where the live lion (sometimes a live actor in a costume) becomes an animation. Begins around the 14:00 mark (Be warned, the film as a whole is pretty dire)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1c6LQWkgmY