He was old enough to have seen the beginnings of American studio animation. And, his career was enduring enough to have seen big changes through the twentieth century. He was resilient enough to survive an early setback as a producer of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. And then, turning lemons to lemonade, he created the character for which he is best remembered. His friends all called him Walt. But alas, the guy I’m referring to is not named Disney.

I’m talking about the other Walt of animation lore: Walter Lantz. How exactly does one assess the legacy of a man who lived in Disney’s shadow? (and, I should add, to such a degree that it encroached on his own name, compelling him to go by the formal Walter!) Lantz spent far more time making Oswald cartoons than even Disney did. There really are some curious overlaps between these two guys named Walt. Because of this, it begs an interesting look at the Golden Age from competing angles.

For instance, by looking at both men as two sides of the same coin, we see just how reactive those formative years of sound cartoons proved to be, a time when studios were desperately trying to catch up with Disney. In this sense, Walter Lantz was an exemplar of being the ‘alternative’ Walt. He succeeded with a prudent business plan, easygoing instead of unyielding and incremental instead of revolutionary.

For instance, by looking at both men as two sides of the same coin, we see just how reactive those formative years of sound cartoons proved to be, a time when studios were desperately trying to catch up with Disney. In this sense, Walter Lantz was an exemplar of being the ‘alternative’ Walt. He succeeded with a prudent business plan, easygoing instead of unyielding and incremental instead of revolutionary.

Rather than steer into headwinds, Lantz generally coasted in the draft made by others. His amiable style worked well, even in those times when business was rough and he had to contend with some real hardships. By the post-war years, his sensible judgment put him in a very enviable position to greatly monetize his studio characters and his vast film library. Yet, as any reader of my column knows, this comfort that he settled into for the long haul was a blessing and a curse.

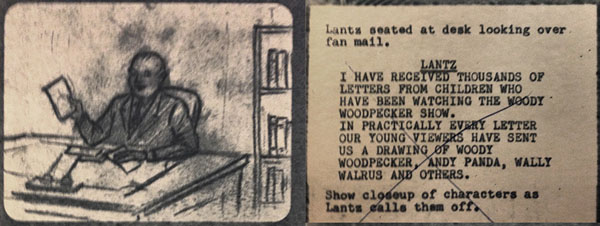

It was during these last twenty years of his studio that he damaged the long-term reputation of his cartoon franchise by releasing so many films that lacked the spirit and quality of his earlier work. Then, through the saturation programming of The Woody Woodpecker Show from the Baby Boom era until the Eighties, this notion of mediocrity was reinforced. It was a case of lumping too much that was bad with all that was good.

As American prosperity grew during the Cold War, both guys named Walt seemed to increasingly withdraw from the nuts’n’bolts endeavor of making cartoons alongside their animators. They took on the trappings of affluent businessmen, with big office desks and meetings to attend with commercial partners. They both were seen on television as themselves, appearing in short vignettes on their popular TV shows. For Disney, this was the pathway to yet another visionary exploit, his theme parks.

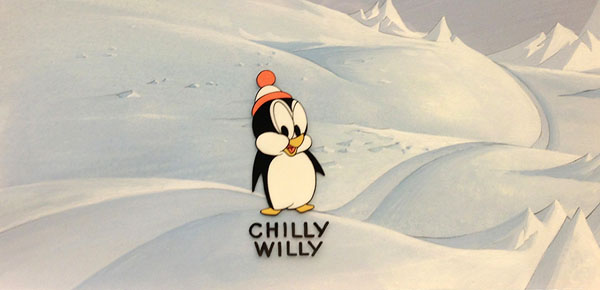

Disney delegated his studio animation to The Nine Old Men, a ‘brain trust’ that promulgated his legacy by creating a new era of less epic and more contemporary films. Meanwhile, Lantz passed on the one thing that could have shored up his prospects for a consequential second act—he let director Tex Avery slip away. With only four cartoons completed before parting ways, Avery nonetheless handed Lantz a priceless gift. He provided him the gag formula that gave Lantz his second biggest all-time star, Chilly Willy; in I’m Cold and Legend of Rock-a-bye Point.

Their quick ‘breakup’, which Lantz later grumbled had stemmed from the hardball tactics of Avery’s lawyer, was likely fomented by lingering resentment from earlier times when the two men were both jockeying for professional advancements at Universal. Avery, for his influential body of work at Warner Bros. and MGM, holds the critical reverence of history, while sadly his own personal life and finances suffered mightily. By contrast, Lantz lived a charmed life, but his later indulgence in easy profit (syndication and saturation) seemed to have dimmed his legacy.

If only the two men could each have traded on their respective strengths and given the other what they each most deserved. Despite Lantz’s estimable achievements, and certainly Avery’s too, the tragedy is what they didn’t do, what they left behind because of a few unsettled points of negotiation in 1955. Had they worked together, and with Avery reuniting with one of his best animators La Verne Harding, the later films of Lantz Productions might have been brimming with classics on par with Rock-a-bye Point.

Another reason to invoke this anecdote is simply to mention how Lantz played roles in animation history even when those connections might not be obvious. When Avery engineered his first studio getaway—leaving for the legendary Termite Terrace in 1935—he brought with him over five years of professional experience working at Universal, developing his signature style while making the ‘anything goes’ Oswald cartoons. However, Lantz was the one who cultivated the atmosphere there and encouraged Avery by eagerly putting his outrageous gags in the films.

In fact, Lantz was a catalyst for the entire westward migration of New York animators during the Depression. When Hollywood saw an emerging ‘gold rush’ for sound cartoons, Lantz and Disney became two men who made destiny. As prominent producers, they crisscrossed Manhattan in 1929 signing animators to lucrative contracts in sunny California, forever tilting the industry west.

In fact, Lantz was a catalyst for the entire westward migration of New York animators during the Depression. When Hollywood saw an emerging ‘gold rush’ for sound cartoons, Lantz and Disney became two men who made destiny. As prominent producers, they crisscrossed Manhattan in 1929 signing animators to lucrative contracts in sunny California, forever tilting the industry west.

And technically, Lantz had been involved in an early sync-sound test (1924) and had made a color cartoon (1930) before Disney did those things, even if these precursors did not impact cinema in the same manner. Like a Zelig of animation history, as an alt-Walt who lived in and shared Disney’s shadow, Walter Lantz always seemed to be near the action.

During the Thirties, Lantz made a notable hire that now ranks as historic. When he promoted La Verne Harding from an assistant to an animator (1934), she became the first woman to hold that role in a Hollywood studio. She continued to work there until 1960, long enough to re-team with Avery. There is evidence that two other women, Xenia Beckwith and Anna Osborne, eventually also worked as animators at Lantz Productions.

Beckwith was part of the wartime animation effort, a time when the Lankershim Blvd. studio had a security-clearance restriction and was visited by Navy brass checking training films. Harvey Deneroff has recently posted about Beckwith’s work at Lantz. Also, I have seen archived production schedules showing that someone listed as “Anna,” presumably Osborne, animated scenes on eight cartoons between April and September 1952.

The legacy of his studio comprises a lot of individual legacies, great and small, and Lantz provided the chance for many artists and directors to pursue their vision without much restraint from him except budgets. Some of his best directors—Alex Lovy, Shamus Culhane, and Dick Lundy—hatched the lunatic persona of Woody Woodpecker and made him both an antagonist and a beloved cartoon star.

Over these last fifty columns, I’ve tried to make light of many of these people working there, the talented individuals who lent themselves to the collective effort under the banner of Walter’s studio. In many ways it’s their stories that form the Lantz legacy as much as the cartoons they made, and I have especially loved feedback I’ve gotten here from families and descendants of the artists.

Over these last fifty columns, I’ve tried to make light of many of these people working there, the talented individuals who lent themselves to the collective effort under the banner of Walter’s studio. In many ways it’s their stories that form the Lantz legacy as much as the cartoons they made, and I have especially loved feedback I’ve gotten here from families and descendants of the artists.

I also want to mention how Walter is posthumously such a generous benefactor to a whole new generation of animators through his Lantz Foundation. I’ve been fortunate enough to work with the Foundation over the last twenty-five years, culminating in my Animation department and LMU’s School of Film and Television receiving consequential monetary gifts from them. This is going toward new construction and technology investments in our program.

Walter’s studio archive of production materials resides at my alma mater, UCLA, and a recent final gift of personal memorabilia, including his 1979 honorary Academy Award, is now housed within Hannon Library Special Collections, here where I work at LMU. It’s been an honor to take part in the effort not just to promote his legacy into the future, but also to be active as a film historian preserving the record of his long and distinguished career.

For this, my fiftieth and last column, I wanted to thank everyone for the great message posts I’ve gotten each time and for all your insights. This has certainly been a great experience. I plan to focus next on a book specifically about the early years of Lantz in Los Angeles, when the ‘two Walts’ competed and carved out a tumultuous beginning to sound cartoons.

Walter Lantz

In fact, Walter’s life nearly perfectly analogizes the span of filmed animation. He was born in 1899, at the dawn of cinema and trick films. He died in 1994, on the eve of Toy Story, the first all-digital feature animation and a harbinger of widespread computer-aided production. When I visited Walter at his office for an interview on September 14, 1993, I ended by asking him some general questions about the industry and its rebound. I was an aspiring animator, still a student then at UCLA with the privileged part-time job of cataloging his archive.

Walter joked with a puckered face that he thought The Simpsons were “ugly,” that it wasn’t really his thing. So I brought up Pixar, wondering what he would say about emerging CGI. His face changed to awe. He answered yes, he had seen the Pixar short films and loved them, believing they were a glimpse of the future. He said he felt they had great characters. Suddenly I was in awe, too. I was looking at a pair of eyes that had seen Winsor McCay perform the original Gertie the Dinosaur on a vaudeville stage and then, crossing all the decades of a century, Walter would behold and enjoy Pixar’s Tin Toy. What a splendorous journey he took during his long, happy life in cartoons.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

This information on Walter Lantz has been invaluable. Thanks for sharing the fruits of your research for all this time. Best wishes on your book.

I loved all your columns about Walter Lantz. I am looking forward to your book. Those tours around the studio on the old Woody Woodpecker Show were what made me want to be an animator and LaVerne Harding was a big help in giving me a start for my first job.

Thanks for this valuable info. Me too, I am looking forward to your book; I certainly hope that it will be more focused on Lantz, the studio, rather than on Lantz, the man (as it was the case with Joe Adamson’s book on him). I guess Xenia Beckwith, who worked at the Lantz studio in the 50s, is Xenia DeMattia (she got that name when married to animator Ed DeMattia), who worked for virtually every studio in the West Coast from the 30s to the 80s.

50 columns? Already?

Thanks Tom; each and every one has been informative and entertaining, Heck, even Babyface Mouse got a mention. If that’s not thorough reportage, I don’t know what is.

Lantz Studios are underrepresented no more.

Good luck going forward.

Your columns have been a joy to read. While you have honestly discussed many of Walter Lantz’ shortcomings, you’ve also shed a lot of light on his many, many achievements and accomplishments. I’ve learned a lot about his legacy from your columns; I look forward to your book.

THanks for the column (to me, Woody would always be synomynous with his pre-1956 shorts, especially the 1940s ones!)

Yeah, especially since people would ignore the good shorts not by Smith that came after that. Seriously, I’m getting really tired of people lumping all the Woody shorts past 1956 together and label them all bad. There are some gems. Just usually not under the disorganized Smith.

It’s a good point, Nic. Yes, there are some gems. I would guess The Bongo Punch (dir. Alex Lovy, 1958) or the return of the “Jack Hannah bear” in Eggnapper (dir. Hannah, 1961) are just the sort of cartoons you have in mind. Count me in as someone who would be interested to read a spirited defense of post-’56 Lantz with a catalogue of the ‘gems’. In general, though, there is a noticeable decline in quality, but that’s not to say that some didn’t rise above. That would make a great guest post here and my spot here is now open!

I greatly appreciate your posts on Walter Lantz. When I watched his Woody Woodpecker Show during the ’60s, it was in syndication. I thought he had one of the greatest jobs in the world because he would talk to some of my favorite cartoon stars.

I’m looking forward to your book for Lantz produced the goofiest West Coast cartoons from 1930-1935. Your analysis on both Bill Nolan and Tex Avery will surely be informative as well as entertaining.

Thanks everyone for the kind words and your interest in my book. GDX, glad you found all the columns “thorough”. But fortunately there’s still plenty more to tell, lots more anecdotes and history to reveal. Gene, thanks for having shared about La Verne helping you get a start in animation. Her work and contributions account for one of the more underrepresented parts of the Lantz studio history.

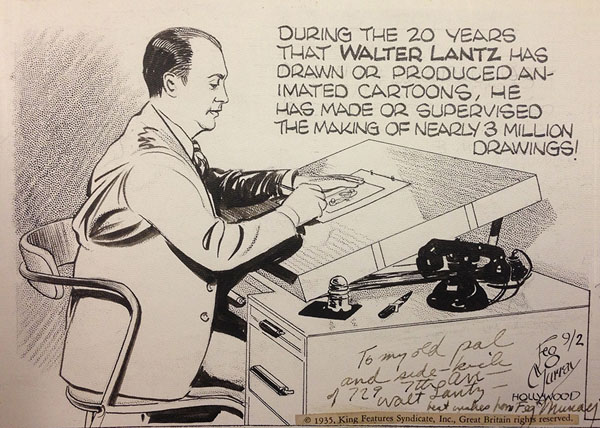

Also, I wanted to point out (because I didn’t add a caption for it) that the comic in which Lantz appears at the top is from the 1930s strip Shooting Stars by Feg Murray, which was kind of an ode to celebrities. Murray inscribed it, “To my old pal and side-kick from 729 7th Avenue–Walt Lantz.” I don’t know what metric was used to calculate the “nearly 3 million drawings” in 1935, the date of this comic, but if that’s the case then imagine how many drawings Walter had presided over by 1972!

2020 will be an Atomic year with the long awaited Tom Klein book on Walt(er) Lantz and the Universal animated story! We’re all rooting for you, Tom.

Hi Tom, hope this finds you well. We’ve recently purchased Walter Lantz’s home in Toluca Lake. He was actually the 39th reisdent of the neighborhood. I’ve been doing some research and your information has been very interesting. I am unable, however, to locate whether Walter had any children?

Put me down as one of the strong supporters who really enjoys the post 1955 Walter Lantz cartoons all the way through the end of the studio. Paul Smith directed some of my favorites, JITTERY JESTER, MISGUIDED MISSLE, THE UNBEARABLE SALESMAN, TREES A CROWD, so on and on into the 1960’s.

All out slapstick cartoons, that’s a good thing around this here cartoony minded person.

Good job on yourWalter Lantz Archive postings Tom, I’ll miss them but will look forward to your book. That takes time and a lot of work to accomplish.

Being on the recieving end of Walter Lantz’z generosity, awarding me a full scholarship while attending CalArts then ending up years later developing THE WOODY WOODPECKER SHOW in the late 90’s, there will alway be a soft spot for the Lantz cartoons from all decades with me.

Again a big thanks for all your writings and archive work.

Thank you for all this info on the Lantz studio. Really appreciate your finding all this rare info.

Thanks for all the Walter Lantz Studios info! Loved every bit of it. I do hope you can write your book and find a publisher.

On another note, I’m still going through my Woody Woodpecker DVD sets, and I saw two that had a strong Tex Avery feel to them: “Private Eye Pooch” and “After the Ball”. I thought I was near the time period that Tex Avery was there in the mid 50’s, and it turns out I was right. “Private Eye Pooch” was released right after cartoons with Tex Avery listed as director, and “After the Ball” was about 4 cartoons later. Is it possible that Tex Avery was the real the director of these cartoons, but that once he stopped working there they decided to put someone else’s name as director in the credits? (And not to take away from the named directors totally — perhaps they did indeed finish and/or shepherd the cartoons after Tex had a heavy hand in them?)

Thanks for the interesting conjecture. Of course, “influence” can a hard case to make with certainty. Did Avery “influence” Smith as his co-worker? I don’t doubt that’s the case, to an extent. Avery had always been influential, and upon his hiring at Lantz in ’55 he instructed animators to undo some bad habits, including what he saw as an inclination to draw too many lines, such as the gathered folds where a character’s arm meets the torso. He told Lantz animators to not ‘overdraw’ lines. However, Avery expressed a displeasure with Woody as a character, and he asked upon hiring not to be assigned to direct any Woodpecker cartoons. Lantz honored this, thereby making it very unlikely that Smith completed a Woody cartoon that had been started by Avery.

Gosh, you can’t just stop making these Walter Lantz columns! There are still some unanswered questions such as, “What did Les Kline do after leaving Lantz in 1972?” to “Who did the layouts and backgrounds for all the Walter Lantz Oswald (the Lucky) Rabbit cartoons from 1929 to 1938?” I hope you can answer these questions and more in the not so distant future.

Sorry to “retire” from the column! I’ll try to answer your questions quickly so I won’t leave behind a cliffhanger: (1) I believe Les Kline retired in 1972 after his long career in cartoons and (2) Bill Nolan created a lot of the early layouts and backgrounds until he passed this duty over to Ernest “Ernie” Smythe, who was an English artist working then at Universal. In the latter half of the 30s, the sophistication of the backgrounds began to improve greatly with the hiring of Edgar O. Kiechle. My post on his work appeared early on, in 2015.

Hi Tom

Any chance you know the whereabouts of any of Walter’s descendants? I have a 3-set of Christmas candles “The Snow Family” that I believe his brother Michael designed for the Emkay Candle Company of Syracuse, NY in 1946. I don’t think Michael had children. Walter’s relatives might enjoy having these candles.

MArk, did you ever find out whether Walter had any descendants? I would love to know if he had children.

Mark and Haig: Walter did not have any immediate family at the time of his death, at which point his beloved wife Grace, his brother Micheal and others had already passed. Despite a suggestion on Walter’s Wikipedia page (“Children: 1”) that he had a child, this is simply not the case. Walter liked to joke that he did in fact have one child… Woody Woodpecker.

Hello, I am a survived relative of walter and possess some of his original works. Would like to get In touch

Hi Ryan! Was excited to see that you are a surviving relative. I have been on the hunt for old pictures… particularly at home. Any chance you could assist me?