The eighth installment of my Censored Eleven series of columns looks at the 1943 Technicolor “Merrie Melodies” episode Tin Pan Alley Cats from Warner Brothers. Some of this cartoon’s content draws from previous cartoons. Animation is reused from earlier films. African Americans are depicted as either jazz musicians or devout Christians, as in Clean Pastures, and borrows from the earlier film’s conflict of religion vs. jazz. Also, the jazz musician Thomas “Fats” Waller is caricatured, just like in Clean Pastures and The Isle of Pingo Pongo.

On the other hand, much of Tin Pan Alley Cats is original. Waller is the only jazz celebrity in the film, and his solo appearance breaks from the ensembles of celebrities in Clean Pastures, Have You Got Any Castles, and the frog cartoons from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Also, the jazz musician is the cartoon’s protagonist–not the star of a random musical number or the antagonist, as in Max Fleischer’s cartoons pitting Betty Boop against a jazz singer. Finally, Tin Pan Alley Cats depicts African Americans as cats. Previous cartoons associated African Americans with creatures having big mouths; MGM’s frogs and the studio’s fish in Swing Social are examples of those designs.

On the other hand, much of Tin Pan Alley Cats is original. Waller is the only jazz celebrity in the film, and his solo appearance breaks from the ensembles of celebrities in Clean Pastures, Have You Got Any Castles, and the frog cartoons from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Also, the jazz musician is the cartoon’s protagonist–not the star of a random musical number or the antagonist, as in Max Fleischer’s cartoons pitting Betty Boop against a jazz singer. Finally, Tin Pan Alley Cats depicts African Americans as cats. Previous cartoons associated African Americans with creatures having big mouths; MGM’s frogs and the studio’s fish in Swing Social are examples of those designs.

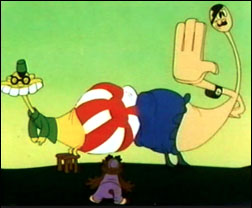

Bob Clampett directed Tin Pan Alley Cats, and he arranged for African American musicians to sing and play instruments in the film. The plot concerns Waller-as-cat shunning religious missionaries to enjoy jazz at a nightclub. A trumpeter plays notes that send the cat into another world, but that world proves to be too chaotic for him. After the trumpeter blows notes to send the cat back to Earth, he flees the club and joins the missionaries–to their astonishment. The animation is frenetic and rubbery, which fits the chaos of the jazzworld Waller-cat enters.

The musicians provide a lively soundtrack for the cartoon. The film was released after civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had started targeting cartoons with ethnic stereotypes during World War II, but Tin Pan Alley Cats escaped the scrutiny of civil rights activists. The cartoon was never reissued as a “Blue Ribbon” in theaters, but it was part of the original television syndication package from United Artists.

So, how did Tin Pan Alley Cats land on the Censored Eleven in 1968? Anything featuring African Americans prominently was a sure target, and this film’s all-black cast was conspicuous. Working against the cartoon were the designs and the dialect. The lips took up the bottom-third of the characters’ heads. The artists took care to depict the lips less like a pair of large ovals and with more “human” features like clefts on the upper lips.

So, how did Tin Pan Alley Cats land on the Censored Eleven in 1968? Anything featuring African Americans prominently was a sure target, and this film’s all-black cast was conspicuous. Working against the cartoon were the designs and the dialect. The lips took up the bottom-third of the characters’ heads. The artists took care to depict the lips less like a pair of large ovals and with more “human” features like clefts on the upper lips.

Nevertheless, big lips are still big lips, and the oversized humanistic lips remind me of when segregationists would say “nigra”–the hybrid of the polite “Negro” and the crude “n-word.” As for the dialect, there’s Waller’s catchphrase “Who dat,” his question, “Where is I at?”, and the answer, “You is out of this world.”

Tin Pan Alley Cats was the last cartoon with a Waller caricature. The musician died in the same year as the film’s release. Perhaps he was given a solo venture, because he was the most cartoony of the jazz celebrities at that time. Warner Brothers had settled into a pattern by then of pitting a short, streetwise protagonist against a taller antagonist. Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong would have been too tall to be protagonists in this mold, but Waller was just right for the wartime cartoon. After he passed away, the animation industry was left without its jazziest muse.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Even prior to the official “Censored 11” this was one of the cartoons banned in the New York City market, when Metromedia’s WNEW (Ch. 5) had the rights to the pre-1948 Warner Bros. package.

WNEW pulled shorts from airing not just for racial stereotypes, but also for overt World War II-themed stories that were both dated, and — post-concentration camp revelations — made the idea of using Hitler in cartoons less palatable for a station in a city with a large number of Holocaust survivors (and it’s the Hitler and Stalin caricatures in Clampett’s revised “Porky In Wackyland” sequence more than the Fats Waller one or the other African-American stereotypes that likely kept “Tin Pan Alley Cats” from getting a re-release. The WWII themes would have dated the cartoon, and by the time it would have been in line for a re-release by the end of 1940s, the U.S. view of Stalin wasn’t as charitable as it had been in 1943).

Waller cat = caterwaul?

Cats Waller?

Thanks, Christopher.

Another region’s experience: in the Omaha NE market, the C11 weren’t pulled until the late 60s, if I remember correctly. There was certainly an African American population, but I speculate there were few, or unheard, complaints in the late 50s – mid 60s. On the plus side, I saw a wide array of classic cartoons, MGM being the only studio seldom seen (except at the movies).

I’m glad to have had them, and I also understand right and wrong. There’s no point in showing these to kids, really, but I do keep them in the video vault.

Like many other complex human endeavors, there are no good sweeping assessments. Tin Pan has many good attributes, and also an obvious downside. For me, the “right thing to do” is to archive them, know them, enjoy them privately, but not go out of my way to champion them.

Waller was 6 feet tall, so the decision to make him short had nothing to do with his actual appearance. In fact, he was a half a foot taller than Armstrong a two inches taller than Calloway.

Thanks for that information, Mark. That leads me to wonder why Waller was always caricatured in cartoons as shorter than Calloway and other jazz musicians. Maybe it was to give him a sympathetic appearance; tall and sizable figures rarely appear as protagonists unless they are dim-witted like Baby Huey. Also, perhaps decreasing Waller’s height made him more palatable to the southern exhibitors who would book the cartoons.

Fats Waller was on the chubby side and I believe the designs follows a common cartoon trope: chubby guys are often drawn shorter regardless of height, almost spherical in shape, as opposed to pot-bellied people who are drawn like pears.

When I first came across this short, I immediately thought of the Disney feature The Aristocats, which caricatured Louis Armstrong as a hep cat (although he was voiced by Scatman Crothers). I think had they drawn the cats without the stereotypcal features, it would have had a somewhat better longevity.

The reuse of soundtrack and animation from September In The Rain (1937) and Porky In Wackyland (1938) kind of cheapen the value of this short as it lacks originality. I always felt that these two elements clashed with each other.

Is there any truth to Clampett’s claim of this short placed in a time capsule as an example of “the music and mores of [the early 1940s]?

Yeah, I’m thinking the prominence of the pneumatic lips caused this cartoon to be withdrawn from distribution, much like Goldilocks and the Jivin’ Bears. Had they been drawn normally like the “black” animals in The Early Worm Gets the Bird and Flop Goes the Weasel, they may have gotten a pass 20-plus years after the fact.

And yet, I’m reminded Scatman Crothers voiced a similar jazzy cat in Don Bluth’s Banjo the Woodpile cat, with a very pronounced bottom lip!

I’ve long been convinced this cartoon’s messiness was a result of Coal Black running over-length and over-budget… the long BG pan at the start, the sloppy reused animation from Freleng’s September in the Rain, and the colorized Wackyland pans make up more than a third of the cartoon. Yet it never really feels lazy; it still all works and the cartoon is pretty fantastic in its original moments, even though the Fats Waller caricature is as bad as humanly possible (see Mark Mayerson’s above comment).

I was recently watching Woody Woodpecker Collection Vol 2 and I noticed a few cartoons that were full of stereotypes of black people. Ex. 100 Pygmies and Andy Panda and Boogie Woogie Man and others. Why no censorship on these Lantz cartoons.?

Different studios, different rules. Most of the black-centric Swing Symphonies weren’t part of the Lantz TV package, but the Andy Panda versus the pygmies cartoons were still airing completely uncensored on Canada’s YTV as late as the mid-90s.

Well, even if the cats were given a different, more cat-like appearance, the premise of “TIN PAN ALLEY CATS” is still loosely based around all-African American musicals or live action films, and regarding the “size” of the Fats Waller caricature, well, the Stepin Fetchit caricature, if that is what it was supposed to be, seen in “ALL THIS AND RABBIT STEW”, was Yosemite Sam-sized. I’m sure that Lincoln Theodore Perry was much taller.

When cartoons like this fell out of favor, there were cartoons that dealt with this premise coming from other studios, although the “devil” was no longer jazz music but too much “fun” in general. For a cat, the fun would be chasing mice, so the angelic spirit was a mouse admonishing the cat and warning him that the “firey furnace” would await him from below. And, again, I wonder what African Americans thought of the earliest cartoon to approach this premise, “GOIN’ UP TO HEAVEN ON A MULE”, a cartoon that came before “SUNDAY GO TO MEETIN’ TIME”. African American caricatures appeared in cartoons through the 1950’s, but they were more African than African American. By this I mean that cartoon cannibals were still seen as protagonists in memorable titles like “CHEW CHEW BABY” from Paramount/Famous and “WHICH IS WITCH” from Warner Brothers, but the humor pretty much mocked more than just the stereotype. In “CHEW CHEW BABY” you were laughing at the way the white tourist treated the tribesmen and how funny it was when the tribesman showed up at his door. It is almost Mel Brooks-ian in its humor, while most of the antics in the BUGS BUNNY cartoon, WHICH IS WITCH” came mostly from all the ways that Bugs out-witted the tribal hunter. It was the usual cat and mouse games, so to speak, perhaps except for the final moment, when we think that an alligator swallowed up the hunter, but perhaps you’ll cover these and other cartoons if this column continues beyond the censored 11.

After all, Warner Brothers was hardly the only studio to create such cartoons. Look at some of the other entries from Walter Lantz and, even, MGM. Such caricatures went far beyond the jazz musician or the harried housekeeper. I’m glad someone did mention, here, how these cartoons never were shown on New York syndicated TV, because, when I became aware of these at cartoon festivals, I wondered how they escaped me, although the BOSKO cartoons from MGM, as part of the HAPPY HARMONIES were in rotation on our ABC affiliate as local time-filling program for kids before the 9:00 morning newscast. I think that the only entry that I never saw before was “BOSKO AND THE CANNIBALS”, and they even aired “UNCLE TOM’S CABANA”, even if only once. The same goes for the GEORGE AND JUNIOR cartoon, “HALF-PINT PYGMY” and the CAPTAIN AND THE KIDS cartoon, “THE PYGMY HUNT”, both of which were shown more than once. Oh, and by the way, who did the voices in “TIN PAN ALLEY CATS”?

According to IMBD, Zoot Watson did the Fats Waller cat, with backing vocals by Four Spirits of Rhythm, while singing group The Four Dreamers were the band from the Uncle Tom Cat Mission. Mel Blanc, as usual, did all other incidental voices, particularly the disembodied lips and the rubber band.

Politically incorrect and reused things aside, I still think it’s a memorable Clampett cartoon and was happy to see it in the “100 Greatest Looney Tunes” book even with the unrestored stills (come on, Warners).

‘Uncle Tomcat’s Mission’ – ouch!

Clampett wanted to give black musicians a gig in Hollywood, and this is how he was repaid. No good deed goes unpunished.

Very true!

Couldn’t he have done it without drawing all the characters in gross stereotypical fashion? He even added pneumatic lips to the friggin’ horn-freak in Wackyland, just in case we missed the point that everyone/thing was in “blackface”.

You touch on a point of contention between African American actors of the 1940s and civil rights groups. Actors playing stereotyped roles often saw their performances as just jobs, and they took whatever roles they could to earn money. Civil rights activists did not like the quality of the roles that Hollywood offered. One strategy of protest was to demand better roles from Hollywood, but another strategy–calling for boycotts of demeaning films–rubbed the actors the wrong way. They worried that they would not be offered ANY roles if stereotyped ones were not available. As for Clampett, he wanted to caricature African American entertainment, first and foremost, and he found willing African Americans to provide the soundtrack. But that doesn’t mean that African American viewers had to be grateful that Clampett hired African American entertainers to make fun of their own culture.

It’s interesting comparing the reused animation to the animation made for this short; the older stuff looks stiffer and more conservative against Rod Scribner’s wild, rubbery animation.

Incidentally, the Wackyland segments would be recycled again for Freleng’s “Porky in Wackyland” remake “Dough for the Do-Do”. There’s a contrast there as well, only on the backgrounds, with the airbrushed saturated colors of “Tin Pan” clashing against Paul Julien’s Dali-inspired gouache backgrounds.

I truly wish the admins of IMDB did not allow the use of bogus voice credits. Everything Tony Ginorio quoted from IMDB is wrong on the voice attributions.

The research I have done for my eventual cartoon voices book-length study will reveal the names with background on some of the artists. I have stopped posting a lot of my information on Facebook or the internet because I prefer to hold onto my advantage after spending big bucks and over two decades of toil acquiring knowledge that other cartoon fans have not had the energy to do (and I have had to travel from Australia to the States each time to dig through archives, all at my own expense), and secondly because every time I correct some erroneous guess it is ignored and the phony names appear all over again a few months later. I’m not trying to hoard stuff, but the net has proven a minefield of poor information and it’s also riddled with thieves who want to know all the facts I’ve learned about, but they have no deep interest aside from a shopping list of names they can quote.

Any idea when that book will be out?