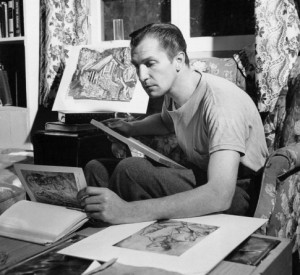

This past summer, in preparation for the opening of Woody Woodpecker & The Avant-Garde — the exhibit which finally opens next week on September 22 — it became clear to me that the strongest personal recollection I could find was right there in the entertaining, sometimes indecorous prose of Shamus Culhane’s autobiography, Talking Animals and Other People.

A page from his book had been my first clue, the one that inspired me years ago and which remains the best and most passionate eyewitness account of the art milieu that gathered in Los Angeles during the years of World War II. Alongside Culhane’s animated and inebriated tales from the Golden Age of Cartoons was this: “Suddenly the arid climate of Hollywood changed, due to the enthusiastic efforts of one ex-New Yorker, Clara Grossman… [who] had an almost inexhaustible knowledge of modern art.”

A sentence like this is a kind of relic trapped in amber, a piece of fine-arts history sealed for decades in this somewhat unlikely spot, an animator’s memoir. It leads us from the Walter Lantz studio to a place called the American Contemporary Gallery. And it also led me to have this experience:

On a recent visit to a notable gallery, housing a collection of midcentury Southern California modern art, I began to understand how deeply the ACG had slipped out of public memory. “What can you tell me about the American Contemporary Gallery?” I asked the owner. Surprisingly, even from this expert in period art for which ACG was a kind of “ground zero” for those artists, the gallery owner did not recall anything at all. “What was the name of the gallery again?”

On a recent visit to a notable gallery, housing a collection of midcentury Southern California modern art, I began to understand how deeply the ACG had slipped out of public memory. “What can you tell me about the American Contemporary Gallery?” I asked the owner. Surprisingly, even from this expert in period art for which ACG was a kind of “ground zero” for those artists, the gallery owner did not recall anything at all. “What was the name of the gallery again?”

That was a revelation that grounded my expectations a bit. The history of ACG was buried in those small artifacts and published remnants that serve as time capsules to a researcher. And the only known living attendee from those years is Kenneth Anger, the filmmaker. The gallery has not been part of the main narrative of the post-war Avant-Garde, so it has largely vanished from the discussion. Fortunately, from those crumbs preserved in some metaphorical amber, we have enough to build up a small framework and put the American Contemporary back on the map.

And among those crumbs hidden in plain sight are the flicker frames of modern art and cartoon art that constitute The Loose Nut explosions, which I’ve written about quite extensively here before. It was never so much that Culhane’s experiments made him a pioneer, but rather that he was one of many ripples that moved outward from a central splash that I recognize as ACG.

David James, a professor at USC, has written the single most valuable scholarly book that touches on the topic, The Most Typical Avant-Garde, which to my knowledge has never received its proper treatment as “an event book” by the editors or reporters of the Los Angeles Times. If Woody Woodpecker & The Avant-Garde can at all start a fire, bringing some overdue attention to ACG, then I certainly hope it will also bring a reappraisal of Prof. James’ fine book.

Yet all was not necessarily lost when this classic gallery slipped out of focus, it was just momentum shifted. The cultural DNA of the American Contemporary Gallery actually does live on and it’s had a big impact. However, it may have lived on in such a vicarious way—through the L.A. County Museum of Art—that the prominence of LACMA as an institution may have snuffed out the memory of ACG!

This is my own conjecture on the matter, but here is my logic for it: after its founding by Clara Grossman, Barbara Byrnes joined as an owner and ran the gallery in the latter half of the forties. Her husband was James Byrnes, who was the first curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at LACMA from 1946 to 1953. The Byrnes were a power couple of the L.A. art scene in the midcentury period, but it would have been the rising status of LACMA that burnished their reputation, not ACG.

When Barbara closed the gallery in 1949, with it went a chance to extend its influence into a new decade. And when that gallery door closed shut, it fell into a dark shadow of history. Like so many things in L.A., celebrities draw all the attention, even posthumously. The actors Vincent Price and George Macready opened The Little Gallery in Beverly Hills for two years, 1943-44, and that possibly remains a more whispered memory in Hollywood lore today. With two actors who were legendary for, respectively, appearing in horror films and playing the villain, one might expect their gallery to be a den of the macabre, but in person they were amiable Ivy League gentlemen who loved art and drank martinis.

When Barbara closed the gallery in 1949, with it went a chance to extend its influence into a new decade. And when that gallery door closed shut, it fell into a dark shadow of history. Like so many things in L.A., celebrities draw all the attention, even posthumously. The actors Vincent Price and George Macready opened The Little Gallery in Beverly Hills for two years, 1943-44, and that possibly remains a more whispered memory in Hollywood lore today. With two actors who were legendary for, respectively, appearing in horror films and playing the villain, one might expect their gallery to be a den of the macabre, but in person they were amiable Ivy League gentlemen who loved art and drank martinis.

Garbo and Hepburn may have been seen with them at the Little, yet the American Contemporary Gallery was really the place that moved the needle and inspired an active community of artists to gather and share their work and ideas. Grossman especially excelled at cultivating group discussions and being a welcoming host. In lieu of other cultural institutions in the city, ACG drew the luminaries of the Avant-Garde who were reshaping art and cinema during this turbulent period.

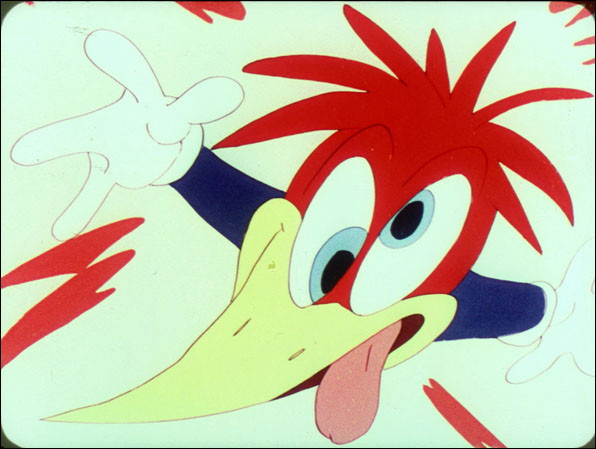

Yet as represented by Shamus Culhane—enthusiastic patron of the gallery and the greatest director of Woody Woodpecker cartoons—I like to imagine how the biggest Hollywood star at ACG was Woody himself, in spirit if not manifested, zipping among the color geometries of Oskar Fischinger, pulsing to the rhythmic edits of Sergei Eisenstein, and rioting to the social activism of Byron Randall. If revolution has a color, it’s red, like the fiery topknot of this brazen woodpecker.

The collection of Byron Randall paintings alone is worth your visit to the exhibit, not to mention the first-ever HD transfers of The Enemy Bacteria, The Loose Nut, and The Greatest Man in Siam, among others. There are also Jules Engel drawings from Fantasia and films by Fischinger and Mary Ellen Bute, courtesy of the Center for Visual Music. Plan to spend an afternoon here; there’s a lot to see and watch.

As the curator of this exhibit, I have been working all summer with gallery director Carolyn Peter to reconstruct the sights and sensations of this historic art venue. It will be quite like no other exhibit you have seen, a collision of fine art, animation, politics, music, a world war, a panda bear, a woodpecker, and a new aesthetic for the modern world. ACG was a small place with a big picture—it was the central splash of the L.A. Avant-Garde.

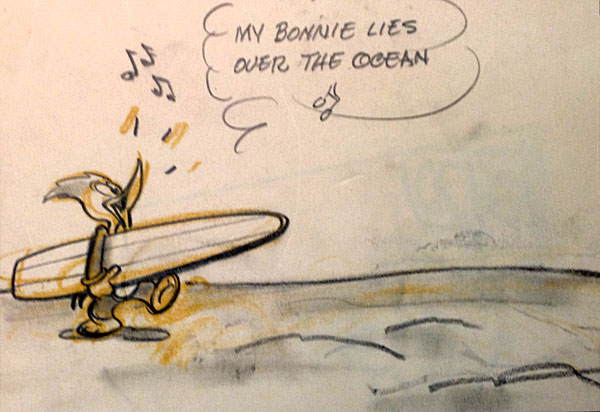

As those rippling waves rode out, they are evidenced by the film experiments of Shamus Culhane. Woody Woodpecker was not the cause célèbre or the agitating stimulus, but he did surf among those interesting currents. The results I think are fascinating and inform us about the connections between cartoons and modernism. I hope you will join me at the opening of the exhibit next Thursday September 22, from 3:00-6:00, at the Laband Art Gallery on the campus of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Woody Woodpecker & The Avant Garde is open from September 22 to November 20. Admission to the Laband Art Gallery is free. Open Wednesday through Sunday, noon to 4:00. All are welcome to the opening reception (3-6pm Thursday the 22nd). For further information visit the LMU website.

This exhibition is co-organized by LMU’s School of Film and Television, College of Communication and Fine Arts, and Laband Art Gallery with generous cooperation from Universal Studios. Special thanks to Steve Stanchfield, Mark Kausler, UCLA Library Special Collections. Images courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Great article Tom. New insights for me.

For those of us manifestly unable to personally experience this exhibit:

Will “WW&TA-G” be recorded for posterity? Thanks.