Over a century ago Charles Chaplin was the biggest box office draw in theaters across America. Getting on the popularity bandwagon were three film studios that turned out nearly 30 Charlie Chaplin cartoons from 1915 to 1923. My latest Cartoon Research book, The Chaplin Animated Silent Cartoons, explores them, and the talented folks behind their production.

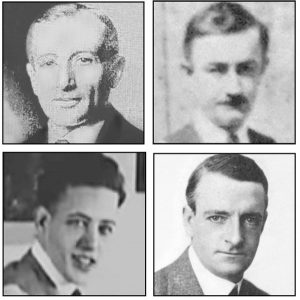

Top row left to right – John Terry, Hugh Shields

Bottom row left to right – Wallace Carlson, Pat Sullivan

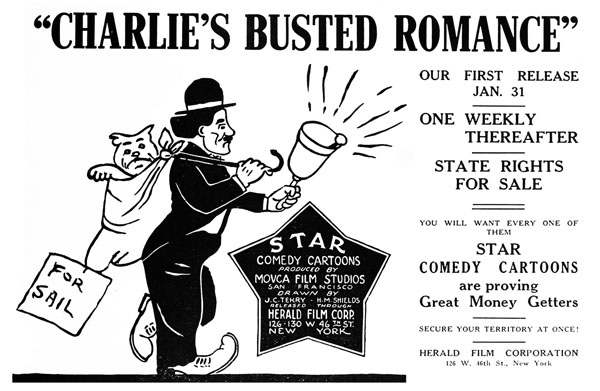

Motion Picture News reported on October 24, 1914, “An invention of importance in the manufacture of comic cartoon films is controlled by this concern [Movca], and it is claimed that pictures of this kind can be turned out in one-tenth the time now required.”

The secretive “invention” involved eliminating frame-by-frame exposures to create movement and replacing it using an art image that moved, or rotated, in actual time when filmed.

Terry and Shields had Charlie Chaplin’s blessing to do the series, figuring it would allow him more publicity, and draw patrons into theaters to see his live-action shorts.

Only a few of the Movca Chaplin cartoons survive today, including Charlie and the Windmill, that often is misidentified on the internet as being produced by Pat Sullivan. If the Chaplin cartoon includes Mabel Normand and Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, which Windmill does, it’s Movca produced. The Essanay and Sullivan cartoons did not include Normand and Arbuckle in their little tramp cartoon offerings.

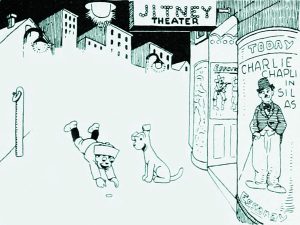

The same time Movca was cranking out Chaplin cartoons, Essanay, where the real Chaplin worked at the time, released Dreamy Dud Sees Charlie Chaplin. The work of Wallace Carlson, his character Dreamy Dud discovers a dime on the sidewalk outside of a theater playing a Chaplin film. He buys a ticket for he and dog, Wag, gaining entry. Dud doesn’t interact with Chaplin, as the star appears only in the context of a projected film. But things do fly out of the screen.

Pat Sullivan’s entry into the animated Chaplin field began, ceased, and was rebooted. Sullivan had been lured by Patrick Powers, treasurer of Universal Pictures, and encouraged to open a studio for the production of cartoons. Power’s initial goal was to get an animated version of William Marriner’s “Sambo and His Funny Noises” comic strip. Sullivan had worked on it as an assistant artist, and with Marriner’s intoxicated death in a house fire of his own doing, the artist came up with an imitation, Sammie Johnsin.

CHARLIE’S WHITE ELEPHANT (1915)

Then two things happened. In June, Messmer was drafted into World War I and served as a private behind enemy lines in France, and Sullivan was convicted of raping a 14-year-old, Alice McCleary, and served time behind bars in Sing Sing. In short order, the studio shut down, until Sullivan was released after a nine month sentence.

CHARLIE IN TURKEY, (1919)

Universal Pictures quickly welcomed Sullivan back, agreeing to distribute his studio cartoon output and release them as part of their Nestor line. As the feature-length epic still required more work, in the interest of expediency, and to increase a profit margin, Sullivan broke the project up into four single-reel cartoons. Each would represent a chapter in the continuing war saga. The first film, How Charlie Captured the Kaiser, was released on September 2.

Otto Messmer, returning to the states after the war, rejoined Sullivan that fall and continued his work on what had now become a Chaplin series. It concluded after reaching 10 adventures in October 1919. Chaplin returned to Sullivan’s cartoons in 1923, when he made a cameo in Felix in Hollywood, a Felix the Cat cartoon featuring notable stars like Gloria Swanson, Ben Turpin, Tom Mix and Cecil B. DeMille.

Charlie Chaplin in animated cartoons continued after the dawn of sound films. The unique thing about the silents is they represent two series, and a couple one-shots. They also are a reflection of Chaplin’s success at that time. America just couldn’t get enough of the little tramp and his antics.

Pat Sullivan, Charlie in Turkey (1919) from Photomediations Machine on Vimeo

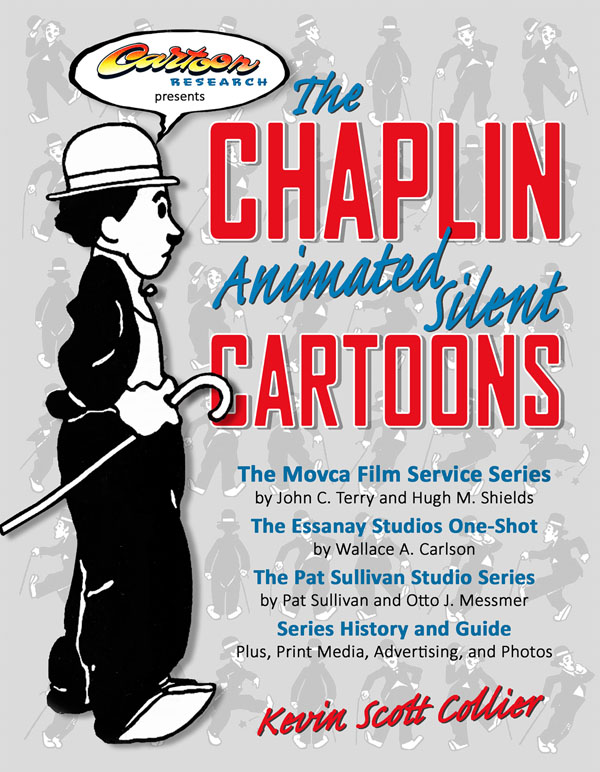

EDITORS NOTE: Here it is. On sale now. Click here or the cover below. Highly Recommended! – Jerry Beck

Charlie On The Windmill has been incorrectly listed as a Pat Sullivan cartoon because of the existing film that was released in 8mm and 16mm by Glenn Photo Supply. I’m grateful to Murray Glass for releasing it no matter who made it. Looking forward to reading more about these cartoons that I’ve been collecting for many years.

Any mention of Baggy Pants and the Nitwits, a DePatie-Freleng entry in the Chaplin sweepstakes? And did its failure mark a dearth of interest in the Little Tramp?

A clip from Chatlie on the Windmill: https://m.youtube.com/watch?feature=youtu.be&v=0qSAYCOptEo

I have worked with Kevin to correct some errors. New orders of the book will have these corrections as no older copies of this print-on-demand book are warehoused.