In a brief essay on G. K. Chesterton, Jorge Luis Borges drew a comparison between the voluminous Briton and Edgar Allan Poe, pointing out that the latter wrote tales of pure fantastic horror and invented the detective story, but never mixed the two genres. As on other occasions, Borges was dead wrong; though it is to be suspected that his error was less the product of diagonal reading than of an attempt to establish Chesterton’s originality. Because any reader of Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (to quote the blueprint for all detective fiction) will notice how, in a deductive tale subjected to an iron logic, the heart of the enigma encloses the most palpable image of the Irrational – a mad ape. On the other hand, those stories belonging to his fantastic horror vein, such as “The Pit and the Pendulum” or “A Descent into the Maelström” are characterized by its strange incursions in the opposite direction when, in the midst of a crisis of uncontrollable panic, their narrators begin to engage in mathematical calculations about the extent, weight or measure of the Unseen. After all, the man wrote “It will be found, in fact, that the ingenious are always fanciful, and the truly imaginative never otherwise than analytic.”

Perhaps in none of Poe’s stories is this characteristic combination of logic and irrationality more evident than in “The Tell-Tale Heart”. Our host does not hate the old man, only his eye, so it is impossible to him to strike when his victim sleeps: the damn eye is out of order. Here we have a perfectly absurd premise developed with great analytical care. The result is terrifying, of course, but with a couple of tweaks here and there it could be also quite comical. An affair for a cartoon, let’s say; and I’m not necessarily referring to the overly literal UPA version. I’m thinking more along the lines of Tex Avery.

An absurd premise, presented in the first minute of the cartoon almost as if it were a mathematical equation, to be logically pursued through a series of gags strung together in a crescendo; this could sum up Tex Avery’s basic formula. The recipe is irresistibly comic in Avery’s hands, but his comedy often has terrifying elements. The relentless presence of a persecutor from whom it is impossible to hide, the unrestrained growth à la Winsor McCay’s or the frequent allusions to insane asylums are motifs that seem somewhat taken from Poe’s horror stories… which, on the other hand, are full of comic possibilities -as R. L. Stevenson rightly pointed out.

In any case, there is a certain familiarity between Poe and Avery. They are two of a kind. Of course, one we associate with horror and mystery and the other we think of as a comedic genius. But it’s fair to suppose that if you grew up in Virginia reading the classics you are more suited to squeeze out some screams from the horrific and the sublime than the laughs you might aspire to get when you graduated from Termite Terrace. And yet, their raw material is more similar than it seems. Or am I insane?

Let us note in passing that this somewhat excessive parallelism bore some fruits. The ineffable IMDB cites Poe as co-writer (along with Rich Hogan) of Avery’s The Cuckoo Clock (1950), and given that the cartoon is a parody rather than an adaptation of a previous story, we must assume a collaboration beyond the grave, through a séance or similar.

More interesting is the still living Poe’s incursion into Avery’s field, considering that neither Tex nor his medium existed yet. “The Angel of the Odd” (1844) is a rare piece in its author’s repertoire, one of Poe’s few forays into comedy that has often been compared to the (yet to be done) films of Chaplin, Keaton and… Tex Avery. A dizzying series of gags featuring madness, fires, falls, blows and an Angel who talks as only Mel Blanc could, leads one to believe that our man in Virginia had a sense of anticipation – even in his lesser known tales – that few could boast.

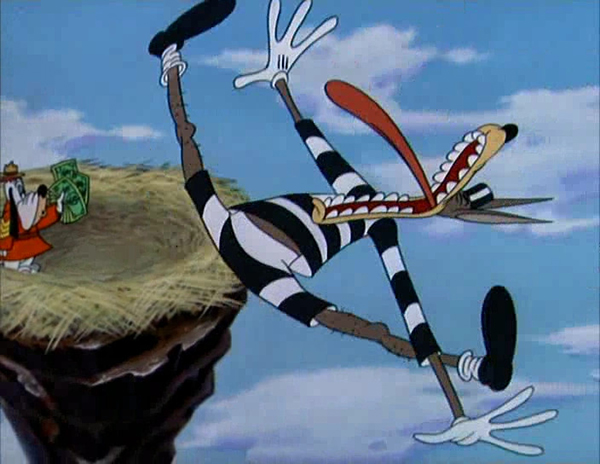

But let’s move on to the evidence, in order to support this audacious thesis. To that end, I have attached to some of the most representative images of Avery’s corpus some of Poe’s best-remembered sentences. I think the result will speak for itself.

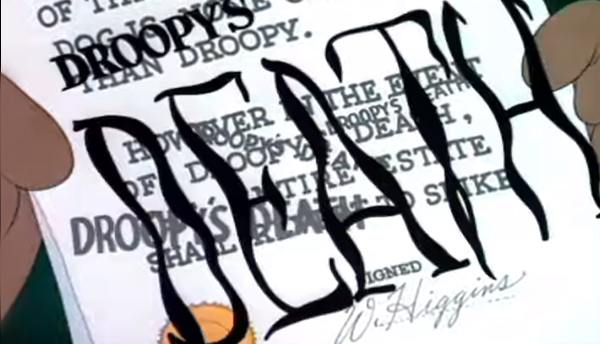

“I think it was his eye!”

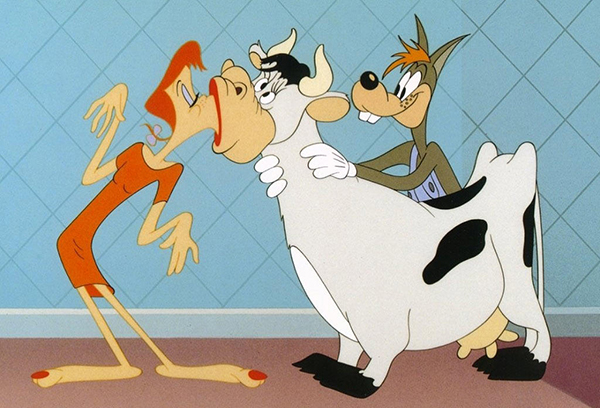

“It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain…”

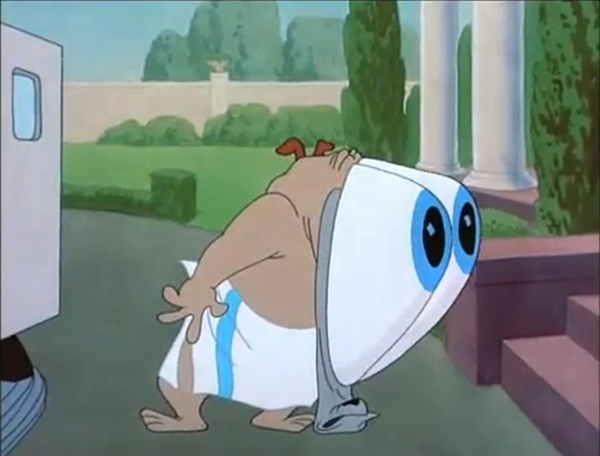

“I knew myself no longer. My original soul seemed, at once, to takes its flight from my body.”

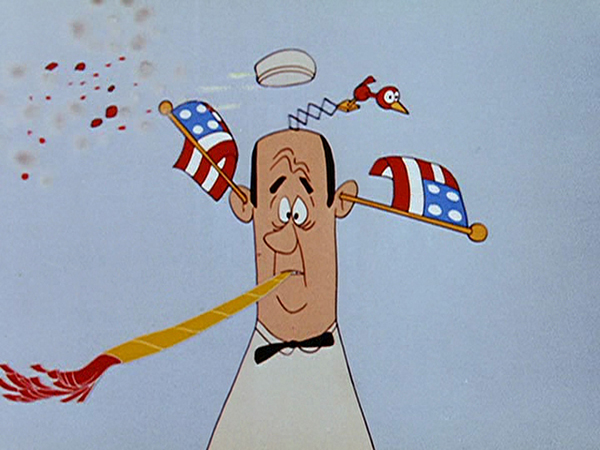

“The disease had sharpened my senses, not destroyed, not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute.”

“Here, here! — it is the beating of his hideous heart!”

“Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing, doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.”

“Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before”

“Long suffering had nearly annihilated all my ordinary powers of mind.”

“Who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or a silly action for no other reason than because he knows he should not?”

Guest Star: Herman Melville.

“Even though white is often associated with things, that are pleasant and pure, there is a peculiar emptiness about the color white. It is the emptiness of the white that is more disturbing, than even the bloodiness of red.”

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Funny you should bring this up. Not too long ago, I was watching Avery’s “Garden Gopher”, and when it got to the scene where the gopher swaps the bulldog’s cigar for a stick of dynamite, and the bulldog loses all his teeth when it explodes, the first thing I thought of was the climax of Poe’s “Berenice”.

Edgar Allan Poe has long been one of my favourite writers. I first encountered his fiction when I was a thirteen-year-old at music camp; the cabin counselor used to read Poe’s stories and poems aloud to us at bedtime. They didn’t give me nightmares, but they did give me an appreciation for great literature.

If you buy a collection of Poe’s complete fiction and poetry — it all fits in a single volume of about 1000 pages — you’ll notice that his short stories are divided into two categories: “Mystery and Horror” and “Humour and Satire”. Having read them all, I can say that there is no clear line dividing the two genres. “How to Write a Blackwood Article” is a parody of a genre at which Poe excelled: a first-person account of a slow and gruesome death, e.g. “The Pit and the Pendulum”. (In the parody, the narrator is enjoying the view of the city from a clock tower but then is slowly decapitated by the clock’s minute hand.) “The Premature Burial” has a tongue-in-cheek twist: the narrator describes being buried alive, but it turns out he just woke up in the dark inside the sleeping berth on a boat. He then resolves to avoid reading morbid stories “like this one.” Most of Poe’s humorous stories, like “Never Bet the Devil Your Head”, contain horrific elements; while some of his best-known horror stories, like “The Cask of Amontillado” and “Hop-Frog”, involve elaborate practical jokes as a means of exacting revenge.

I’m glad that you mentioned “The Angel of the Odd”, which is probably the most cartoony of all Poe’s stories. The angel has a body comprised of flasks, casks, bottles, and other vessels for holding alcoholic beverages; and he speaks with an exaggerated German accent, at which, as you noted, Mel Blanc was highly adept. Poe’s alcoholism was the great tragedy of his life, but he wasn’t above playing it for laughs.

When I was an undergraduate I wrote a paper comparing the poetry of Edgar Allan Poe with that of Dr. Seuss. They both favoured anapaestic couplets, often invented words for the sake of euphony, and had a predilection for the grotesque, the absurd, and the subversive. And what cartoonist was more grotesque, absurd, and subversive than Tex Avery?

Lovely–this is a good parallel to the mantra I’ve been pushing for all who’ve cared, “Manga author Junji Ito is a comedic genius.” He, too, deals primarily in the one-and-done short story, dances with the absurd on a regular basis, and relies on pushing as much motion and malleability of the human face/figure as possible. In a way, for how much people view him as a purveyor of pure trauma, he’s much closer to Tex Avery and artists of similar ilk than often thought. It’s a shame no adaptation of his work seem to capture this madcap aspect of his work–cartoons end up flat and even Ataru Oikawa’s Tomie is a tonal departure into a (solid) slow-burn suspense flick.

Generally, there’s a fine line between horror and comedy, which is how you get from the no-holds-barred original Evil Dead film to the somewhat comedic sequel, before finally culminating in Medieval Looney Tunes for Army of Darkness. It’s no shock that Tex Avery’s films could remotely dip into the territory or vice versa.

In terms of Avery and Poe’s crossing of influences, I think the short that best matches the two is “Sh-h-h-h-h-h”. The concept could work for either creator – a man on the verge of a breakdown, trapped in the quietest place in the world and haunted by deranged, otherworldly laughter. The differences, of course, would be whether the story is told through the written word or the silver screen.

Excellent post. Most 40s cartoons are freaky in more ways than one!

IMO, Tex Avery should be called a great American filmmaker. He deserves a place among the greats like John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston.