In 1956, America was smitten with the good intentions of Alberta Siegel and suddenly cartoons were under scrutiny. For her Stanford doctoral work in psychology, she had arranged for twelve preschool children to watch the Comicolor cartoon The Little Red Hen (1934) and another twelve to watch what is described as “a Woody Woodpecker cartoon.” Afterward she observed the kids at play. You guessed it, she perceived the Little Red Hen group to be engaged in gentle play and the Woodpecker group was more likely to hit each other and break toys.

Meanwhile, in that same year, Stanley Kubrick directed his first succesful feature film, titled The Killing no less. It might seem insane to think that there are any cinematic links between these events, but as Kubrick’s career progresses the argument could be made that he had obviously watched some Woody Woodpecker. Not just any cartoons, but specifically the brutal ones directed by Shamus Culhane.

Meanwhile, in that same year, Stanley Kubrick directed his first succesful feature film, titled The Killing no less. It might seem insane to think that there are any cinematic links between these events, but as Kubrick’s career progresses the argument could be made that he had obviously watched some Woody Woodpecker. Not just any cartoons, but specifically the brutal ones directed by Shamus Culhane.

References to Alberta Siegel’s research invariably name this one very specific Ub Iwerks cartoon and yet the identity of the violence-inducing Lantz cartoon is obscured with a generic citation—it’s enough to call it “Woody Woodpecker.” For her entire life, and even within her obituary, it is always mentioned in newspapers this way. Yet, by 1956, the Woody series had gone through many changes over sixteen years and was handled by a number of directors: Alex Lovy, Walter Lantz, Culhane, Emery Hawkins, Dick Lundy, Paul J. Smith and Don Patterson.

If I were Siegel and was hoping to gin the results for a strong contrast, I’d definitely cherry-pick from the best of Culhane. Besides, older film prints would have been easier for her to acquire. Some perfect choices include The Loose Nut, Woody Dines Out, Who’s Cookin’ Who? or the pure sadism of Barber of Seville. After the period of Culhane’s cartoons, the hostile exuberance went out of Woody quite a bit, but these violent exemplars from the WWII era continued to be widely shown and would certainly have been available for Siegel to show the kids.

If she opted for one of these titles then there’s some irony because Culhane also had a featured role on The Little Red Hen as animator and co-director, so he might deserve credit for pacifying the one group of preschoolers while then inciting toy-smashing mayhem in the other. Lovy was the director just before Culhane. His cartoons had the crazy-looking design of Woody with buckteeth and fat legs. Lovy’s wartime cartoons shared the same violent humor, owing to their continuity with story artists Milt Schaffer and Bugs Hardaway.

It is worth noting that the frequency of guns increased in the post-war cartoons, part of an overall trend in media for gun-toting action genres. Woody puts a gun to his head in The Coo Coo Bird (1947) and begins starring as a cowboy in a number of cartoons with holsters and six-shooters. However, the film-mediated aggressions that Siegel observed were hitting and breaking, not imaginary gunplay. Maybe that worked out because the Schaffer-Hardaway story team preferred the cruel intimacy of knives, blunt objects, and even meat grinders.

It is worth noting that the frequency of guns increased in the post-war cartoons, part of an overall trend in media for gun-toting action genres. Woody puts a gun to his head in The Coo Coo Bird (1947) and begins starring as a cowboy in a number of cartoons with holsters and six-shooters. However, the film-mediated aggressions that Siegel observed were hitting and breaking, not imaginary gunplay. Maybe that worked out because the Schaffer-Hardaway story team preferred the cruel intimacy of knives, blunt objects, and even meat grinders.

Up to that point, conventional wisdom prescribed that watching film violence was cathartic and would mitigate aggression in an audience. However, soon Dr. Siegel was famous for disputing this idea and the American press effusively covered the story. She launched a whole cottage industry of research-driven social science around media violence which endures to this day. The momentum for this concern was probably not that kids might imitate Woody, but rather that a handful of skilled animation directors—Avery, Jones, Culhane, Hanna and Barbera—had pushed cartoons to such an outrageous level of notoriety.

It was the adults who were shocked at their children’s delight in seeing bombs, weapons, rockets, dropping anvils and unchained malice. And it turns out that we were those kids who laughed so hard at what we now call “the classics” and our disdain is often reserved for the softer TV-edited versions. The Woody Woodpecker Show started airing the following year, in 1957, and the more we watched it the more our deviant behavior was studied by psychologists.

Yet some kids are different than others. Shamus Culhane and Stanley Kubrick both became involved with the film industry as young New Yorkers. Both of them became obsessed with Russian film theorists and were deeply inspired by reading Pudovkin’s Film Technique. The films of Eisenstein and Pudovkin held a vast influence over these two directors. Although they were 20 years apart in age, the zeitgeist of the 1940s proved to be a formative period for both of them, and in this decade they steeped themselves in classic literature, avant-garde cinema, and modern art.

As a young man, Kubrick owned a copy of Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and also Prokofiev’s record soundtrack for it—this must have been the cantata version available on the 1949 Columbia Masterworks label. Kubrick obsessively played the movie over and over on a home projector, always trying to sync the music, leading his kid sister Barbara in a fit of rage to break the vinyl disc in front of him. It’s interesting that this was exactly the sort of behavior Siegel was able to tease out of 4-year-olds with a Woody cartoon just a few years later.

As a young man, Kubrick owned a copy of Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and also Prokofiev’s record soundtrack for it—this must have been the cantata version available on the 1949 Columbia Masterworks label. Kubrick obsessively played the movie over and over on a home projector, always trying to sync the music, leading his kid sister Barbara in a fit of rage to break the vinyl disc in front of him. It’s interesting that this was exactly the sort of behavior Siegel was able to tease out of 4-year-olds with a Woody cartoon just a few years later.

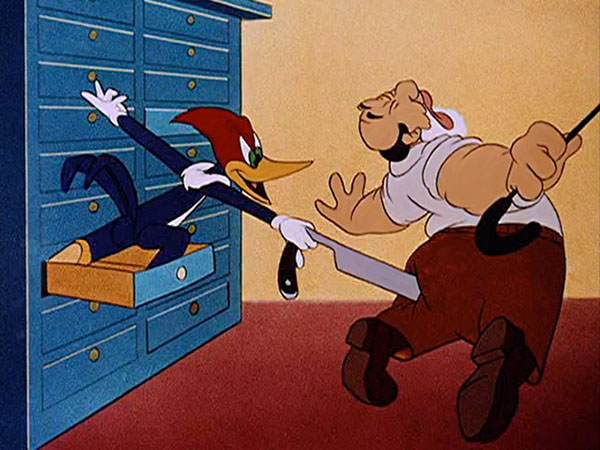

Which brings us back to Culhane, working at the Walter Lantz studio in 1944, where he made his great classic of animated violence, The Barber of Seville. In it, Woody sings a speed-track version of the aria from this famous opera. “Figaro, Figaro” he sings as he terrorizes a barbershop, gleefully slashing a straight-edge razor at his innocent victim. This is Woody reaching his psychopathic peak as a character. As an avid moviegoer who was “brought up on a diet of Hollywood movies” according to his friend, Kubrick would have had plenty of chances to see it playing as the cartoon before a feature.

Culhane relates in his autobiography that when he saw the Schaffer-Hardaway storyboards he “knew right away this was my opportunity to use the theories” of fast-cutting and daring edits from Eisenstein and Pudovkin. And since Barber of Seville was released into theaters when Kubrick was only a young teen, there’s a chance the cartoon’s musical finale made an impression on him. At the very least, it’s amusing to think ahead just a few more years, with Stanley driving his sister to madness in the family home, Prokofiev’s symphony roaring from the record player while Eisenstein flickers on a wall. Over and over, totally annoying, just like Woody Woodpecker.

The publicized efforts of Dr. Siegel and others began to have some impact on the Walter Lantz studio in the 1950s. With a new flow of studio profits coming from television, Lantz had no motivation to bring back the unchecked animus of Woody’s earlier persona. Lantz didn’t need his studio to be in the crosshairs of this growing national debate. The woodpecker remained a brat, but gone were the days where he was criminally insane, fully deserving a lock-up in Arkham Asylum.

As Woody became milder, Kubrick was growing more successful and increasingly subversive with his movies. If the films of Culhane had planted a seed in young Stanley, then it’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) where all that conditioning-by-cartoon finally manifested. The mishievous Culhane had gotten away with many indiscretions on account of WWII. America had bigger fish to fry than to adequately censor the wartime cartoons. Taken together, Culhane’s pranks and experiments at Lantz constitute some central aspects of Kubrick’s chilling film landscape.

1. Erotica. A Clockwork Orange opens at the Korova Milk Bar, where the Droogs and other bar patrons sit on naked sexualized chairs. It is the first of many erotic objects and artwork seen throughout the film, showing sex visualized as aggression in this dystopic future. In Culhane’s The Greatest Man in Siam (above), arriving suitors compete to win the princess. He and background artist Art Heinemann pranked the backgrounds of this cartoon with lots of images of phalluses and vulvas, allowing the subtext to spill right out into the open.

2. Modernism. Kubrick built a stylized world of the near-future with sculptural furniture and abstract art. In Woody Woodpecker cartoons, Culhane had populated explosions with flickering bursts of modern art inspired by his interest in non-objective painting. More on this can be found in my previous post.

3. Classical Music. Alex the Droog achieves a kind of ecstasy listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to pleasure himself with violent fantasies. Quite the same might be said of Woody and Rossini’s “Largo al Factotum”—that’s the proper Italian title of the “Figaro” song. What else but some cruel fetish for opera explains that savage finale of The Barber of Seville?

The scene that many consider to be the single most depraved in A Clockwork Orange is the home invasion. Preying on the kindness of strangers, the Droogs brutalize a middle-age couple while Alex sings and dances “Singin’ in the Rain.” This flips the smiling cheer of the American Musical on its head and leaves audiences gasping in horror to see Alex savagely beating a man during the improvised performance.

Of course, Woody had performed his on-screen brutality almost thirty years earlier, but as directed by Culhane the sequence stays just on this side of comedy. Without any provocation, he repeatedly swings his weapon but the man keeps dodging and then Woody allows his victim to escape the barbershop. Kubrick took the same notion to a very dark place and, in doing so, his film endures as one of the most provocative polemics on a modern society diseased with narcissism and casual violence.

At the end of the movie, Alex is detained by authorities and the fictional Ludovico Technique is used on him, an aversion therapy where his eyelids are peeled wide open and he watches lots of violent media to be cured. Dr. Siegel was surely not amused. By 1971, roughly 3000 psychological studies had been conducted, forming a convincing pretext for her crusade against letting young people see exactly this sort of thing. If Kubrick thought his movie would be a stimulus for mostly parlour discussions, he was mistaken.

At the end of the movie, Alex is detained by authorities and the fictional Ludovico Technique is used on him, an aversion therapy where his eyelids are peeled wide open and he watches lots of violent media to be cured. Dr. Siegel was surely not amused. By 1971, roughly 3000 psychological studies had been conducted, forming a convincing pretext for her crusade against letting young people see exactly this sort of thing. If Kubrick thought his movie would be a stimulus for mostly parlour discussions, he was mistaken.

A Clockwork Orange was seen as yet the latest vulgarity and among the worst ever. Fears that it would incite violent behavior only ignited when there were reports of numerous copycat crimes, especially in England. The gang of Droogs became a flashpoint in a rising tide of controversy. At the time, Dr. Siegel was an influential member of the U.S Surgeon General’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior. A growing controversy like this only bolstered her claims. At Kubrick’s suggestion, Warner Bros. withdrew the film from release in the U.K.

In 1972, speaking at Senate hearings, Dr. Alberta Siegel said, “There is now evidence for a causal link between watching TV violence and subsequent aggressive behavior by the viewer.” Executives at the networks were finally compelled to make amends with public policy groups and government agencies. The era of sanitized cartoons was beginning, a culmination of efforts first sparked in 1956 by her case study of twelve kids and a one-reel Woody cartoon.

Yet the mystery remained for me. Which Woody Woodpecker cartoon did she show? I was curious enough to go to my university’s library and track down her original published research, titled “Film-Mediated Fantasy Aggression and Strength of Aggressive Drive.” The answer, it turns out, was in a footnote, overlooked by all the mentions in the newspapers over the last sixty years. The cartoon was Ace in the Hole, directed by Alex Lovy.

It was released a year before Culhane arrived at the Lantz studio and of course the story development was by Schaffer-Hardaway, so it had much of the DNA of Culhane’s films. It even had the crazier-looking design of the original Woody, but Ace in the Hole does not have what counts most. Woody in this film is not an unprovoked maniac who is willfully wreaking havoc, but instead he is caught up in a comic battle with an implacable military superior. He’s sympathetic.

It’s a relatively tame sample from among the wartime cartoons, in my opinion, and perhaps for the sake of the Lantz studio that was a good thing. What if Siegel had observed some off-the-chart “strength of aggressive drive” instigated by one of Culhane’s sadistic classics? Then again, these were preschool kids she studied and possibly they registered no difference between slapstick and smashmouth.

Maybe only a child ten years older would truly feel the pull of red-headed corruptibility.

Would some impressionable kid watch The Barber of Seville and plumb the depths of its smiling insanity? Well, perhaps Stanley Kubrick saw it as a young teenager and he never forgot it. We don’t know if he subsequently hit his friends and broke toys, but we do know that his little sister smashed his favorite record to pieces. The rest, as they say, is history.

In 1948, Columbia Records began making phonograph discs as LPs with vinyl instead of a shellac compound, and this was an innovation that quickly became industry standard. When Columbia issued Profokiev’s Nevsky score the following year, it was a highly promoted release that could be purchased in various colors: blue, green, pink and orange. I like to think Stanley Kubrick had the orange cover. The album was hyped for its “long playing microgroove” and, on account of the flexible new vinyl format, it was also billed as being “nonbreakable,” which clearly young Barbara Kubrick debunked. Some accounts have her smashing the LP over her brother’s head, but based on a direct source from a childhood friend we do know that, whether or not she hit her brother with it, “she broke the record in an absolute rage.”

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Thank you for tracking down “Ace in the Hole”. Hooray for original animation research!

Osamu Tezuka said that he had been tempted to dedicate his 1980 animated feature “Phoenix 2772” to Walt Disney and Stanley Kubrick, who were both deliberate influences on it. His protagonist Godo (= Godot, as in “Waiting for Godot”) is tortured, and at the end the Earth is destroyed.

I don’t know about “Alexander Nevsky”, but in the early days of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization, Mike Jittlov (who was not a member) contacted us and asked if he could provide a 16 m.m. surprise program. We said sure, expecting some of his pixillated shorts, or maybe he had some Japanese animation that we weren’t familiar with. He arrived with his family and a print of the Soviet 1950s live-action “The Sword and the Dragon” (“Ilya Murometz”), the heavily-edited U.S. release, unfortunately. It was one of the very rare C/FO meetings where the program was not Japanese animation, although nobody complained. It’s a beautiful film, and if it wasn’t a cinematic influence on Japanese animation, it should’ve been.

The New Republic posted an article — actually a series of tweets — a couple of months ago on the influence of Disney’s “Three Little Pigs” along with Road Runner cartoons on Stanley Kubrick. I’m not sure if it was that as far as the cartoons went, or that, post-“2001”, Stanley did most of his movies for Warner Bros. and no rights fees had to be paid if a Road Runner or Bugs snippet that fit the bill was used.

Danny and Wendy Torrance watch a Road Runner cartoon (can’t remember which one) on TV in The Shining(1980).

Would it be fair to say, or speculate, another reason that Woody became less frenetic around this time is because Lantz signed a deal in 1957 to put his Woody cartoons on a TV programme squarely aimed at children?

Lantz mentioned he had to censor some of his old cartoons and it would seem logical on his part to make future cartoons hew to TV standards to avoid future editing.

Lantz has also stated that he got orders from the execs at Universal to tone Woody down.

I have watched Woody Woodpecker in Barber of Seville and Bugs Bunny in Rabbit of Seville side by side. The Bugs Bunny version is way funnier. Great gags and great timing. Hilarious lyrics for the music. Plus, since Elmer attacks Bugs first, you are on Bugs’ side all the way through. In the Woody Woodpecker version, the violence against the poor victim of Woody is totally unprovoked, so all the way through I am on the victim’s side. That made it a less funny cartoon too.

My hat is off to you for such an excellent piece. I have one small contribution. Nonbreakable vinyl is indeed breakable – I have firsthand experience. That said, I will put forth another theory: perhaps Kubrick had an earlier release in his collection. The same recording of the Prokofiev music was first released by Columbia as an album of shellac 78s in 1945, while the vinyl Lp single disc you included above was released in 1949. Shellac 78s of course were VERY breakable – almost comically so. Just a thought. Also a footnote: the cover illustration of the Columbia Lp you featured was by Andy Warhol – one of his first commercial jobs upon his 1949 arrival in New York City. There is speculation elsewhere on the ‘net that the illustration itself was inspired by Eisenstein’s film, which Warhol himself may or may not have seen.

“we do know that his little sister smashed his favorite record to pieces”

I’m with the record company on this one. I think that story is apocryphal, no matter who told it. There’s NO WAY she could’ve smashed a 1949 Columbia LP pressing to pieces. Those suckers weighed in at 180 to 210 grams – the same (or more) as the ultra-thick audiophile pressings today, and the vinyl was more break-resistant than the current stuff. It was also not flexible. except perhaps compared to shellac pressings. In any case, you’d have to do an act of *very* vigorous violence to it to even chip the edge.

Now she certainly would’ve been able to quickly render it unplayable with a sharp object, but not break it. And even the shellac 78s would have had Columbia’s patented laminated core construction, which is also surprisingly impervious to breakage.

If it was a later pressing, say 1956 forward, then it would’ve been thinner and more easily smashable.

The cartoon in which Woody puts a gun to his head was “Wacky Bye Baby”, not “The Coo Coo Bird”. (Both films were directed by Dick Lundy, btw.)

Thanks for all your comments everyone, I really appreciate having the feedback. And Nick, I hadn’t realized that Columbia had released a set of shellac 78s in 1945 for Prokofiev’s Nevsky. Knowing that, I’d amend to say that yes, Kubrick’s sister certainly might have smashed one of those. But 1949, when the vinyl LP was released to significant fanfare, does seem about the right time period to place this event. As far as I can gather, Kubrick was not a Soviet cinephile until he was a young man, not a teenager, and if he was 21 in 1949 then that seems about the right time for this to have happened. Also, to Eric, I should mention that if she broke the vinyl LP to pieces it might have just been TWO pieces, so I could have been clearer in what I was implying. Again, I am speculating from the various information, so any input from all of you I’m grateful to have.

“if she broke the vinyl LP to pieces it might have just been TWO pieces”

I’m still maintaining she couldn’t have done that. Those earliest Columbia LPs weren’t like the thinner ones a few years later. She could’ve jumped up and down on it and it wouldn’t have broken. Scratched beyond playability, absolutely. But not broken.

Eric, I love your conviction; I enjoy getting good intel like this. Since I’ve never handled one of those early Columbia vinyl LPs, I was not aware they were markedly different or sturdier than later LPs, which I’ve personally seen get broken. I assumed “nonbreakable” was typical marketing hubris like White Star Line’s famous “unsinkable”. Taken together with Nick Rossi’s suggestion, maybe this leads us to think it was the disc set from a 1945 issue of shellac 78s, VERY breakable. I’m still assuming this incident took place in the late 1940s, though, based on when Kubrick got into Eisenstein, but this allows that maybe it happened in ’48 or ’47, or was it ’50s? The Columbia marketing campaign to introduce Prokofiev’s LP would really have pushed it to public attention in 1949, so that is still reason to think 1949 is a likely year. Yet, because of the value now of those Nevsky LPs, with album cover art by then-unknown Andy Warhol, I don’t suppose anyone wants to try to snap their vinyl in half in the name of film historians proving a point! Unless a key source can give us direct information on this, we’ll never know for certain.

ANd then along came Paul Smith, and by the 1960s he was the only director of Walter’s shorts, so Alberta Siegel got what she wished for if she were still alive by the late 60s (Chuck Jones,too, had WAY toned down with the cartoon specials he was doing by this time..)

Yet, “How the Grinch Stole Christmas” is in my opinion, one of the best Christmas special ever made.

I’m curious as to where on the Universal lot the Walter Lantz Studio used to be located. There’s a statue of Woody across from the studio commissary, but I doubt asking anyone there now would yield any info. “Walter Lantz…who’s that?”

Wait, there’s still a Woody Woodpecker Statue in the Universal lot? Is it available for the public to see?

Stanley Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, features the son of the main characters watching The Fright Before Christmas section of Bugs Bunny’s Looney Christmas Tales. Frustratingly it cuts before Speedy Gonzales’ one line, which would have fit the film perfectly. After all, what better describes Tom Cruise’s nighttime activities than “I’m stirring, and I’m a mouse”.

Not sure I see any real evidence of a Droog/Woodpecker connection, but I’d say Woody actually is sympathetic in “Barber”, because as alarming as this unstable character with a sharp object may be, his intent is clearly not to kill but to shave. Classical music does seem to motivate his hyper side, so if parents can blame Woody for inspiring violence in kids, Woody can blame Rossini.

Interesting read, and congratulations on finding out the cartoon she was talking about. Much of what you write about happening in “A Clockwork Orange” is actually from the original novel. So you can now start wondering if Anthony Burgess was the one who watched Woody Woodpecker! I do know that Kubrick’s American TV viewing was mostly about NFL football & TV commercials, which he liked very much.

Tom & Co. —

Kubrick became a film maven who haunted movie theaters and the Museum of Modern Art, but it’s not clear at what age that started — Probably saw a lot of movies in theaters (NOT television) even before he was a teenager, but at 16 he became a photographer for LOOK, and probably started attending MOMA about that time — Lantz and Kubrick are 2 of my favorite subjects, and I never saw any connection between them before — but I do know that when Kubrick was preparing DR. STRANGELOVE he cited 2 important instances of the use of violence in American humor: Donald Duck and Tom & Jerry (I think that’s who he cited: If he’d said “Woody Woodpecker,” I’d have remembered that for sure!

Kubrick had Shamus Culhane’s MY DADDY THE ASTRONAUT accompany 2001, A SPACE ODYSSEY.