When Universal Pictures told Walter Lantz in 1939 that studio finances were in such bad shape that they could no longer give him the advances he needed to make cartoons, they were, in short order, terminating his contract. Refusing this, Lantz implored them: he would accept a contract even without receiving his weekly advance. These terms were obviously different than what his old friend and competitor Walt Disney had faced over ten years prior—also working then producing cartoons released by Universal—when he was pushed out in 1928.

What Lantz did to become an independent producer was, in many ways, just as courageous as what Disney had done after getting the boot. He risked everything arranging a deal that would allow Universal to extend him a contract. He mortgaged his own home, solicited investments from his Hollywood friends, took out loans, and generally did everything possible to finance the working capital for his studio. Of course, the risk could be made worthwhile if the terms of the deal would give him real ownership.

Fortunately, the studio acquiesced in January 1940 when he negotiated a pivotal concession from Universal. Lantz would receive ownership and merchandising rights to the characters in his cartoons retroactive to 1936. Under these terms, Walter Lantz Productions entered a contractual agreement to continue delivering films. Lantz fronted all the production costs and the two parties shared in the profits.

Fortunately, the studio acquiesced in January 1940 when he negotiated a pivotal concession from Universal. Lantz would receive ownership and merchandising rights to the characters in his cartoons retroactive to 1936. Under these terms, Walter Lantz Productions entered a contractual agreement to continue delivering films. Lantz fronted all the production costs and the two parties shared in the profits.

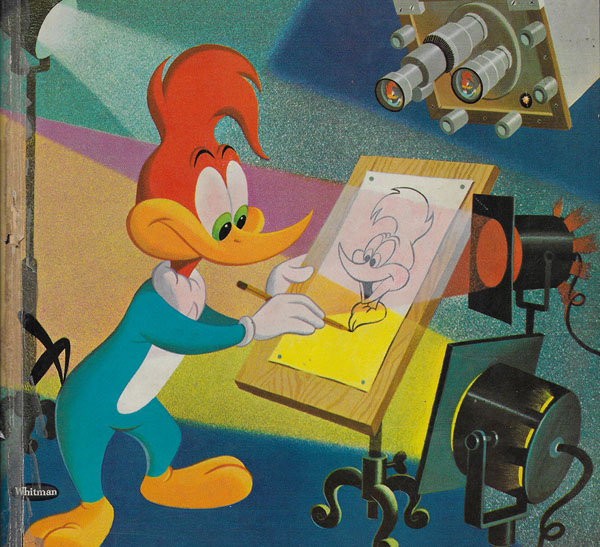

Just as Disney found that independence brought a sudden and overwhelming change in fortune, so too did Lantz. Only three films into his new contract, he introduced Woody Woodpecker. The rest, as they say, was history. Yet much less is said about a smaller avenue by which both men made additional revenue and extended their cartoon brands: they signed with the partnership of Western and Dell Publishing to offer licensed comic books using their beloved characters.

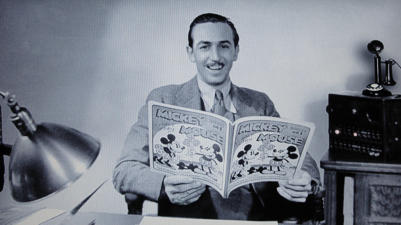

In fact, these comics, especially in the case of Donald Duck, really opened up a greater venue of popular appeal, as the film audiences then sopped up these characters going on to new adventures in print. The Disney studio first cultivated this aspect of brand extension in the 1930s with newspapers strips and then Mickey Mouse Magazine, which paved the way for its deal with Western Publishing.

It naturally turned out that working as an assistant to the animators was a good training ground for drawing for the strips or comic books. Floyd Gottfredson moved on from being an assistant to drawing the Mickey Mouse strip and Leo Salkin once even remarked in an interview with Joe Adamson that he thought Carl Barks was a mediocre gagman at Disney in the 30s, only then to be surprised by his later success on those Duck comics.

I mentioned in a previous post how another artist Al Taliaferro was the first to depict the St. Bernard from the animated cartoon Alpine Climbers as a recurring comics character who went on to bear the name Bolivar, which I have speculated may have been an homage to Bolivar the Talking Ostrich, a character created by Pinto Colvig with the help of Walter Lantz.

So let me use this moment to mention another speculation, which—as with my Bolivar inquiry—I’m hoping one of you may have some supporting (or refuting) information to help me out. So, let us start with Colvig, a fascinating guy who was among the players in Los Angeles involved in the ‘gold rush’ to make the first successful sound cartoon. And below, here’s a few pieces to examine: an inked rendering by Pinto of his stage name, a signate logo of the Disney corporation—which was not really Walt’s signature—and a signate logo of Walter Lantz Productions, which actually was his, though refined by publicity artists.

More on those signatures in a moment. As an entrepreneur who had owned his own small studio in San Francisco, there is no telling how much Colvig may have inspired Lantz, at least insofar as ‘showing him the ropes’ when they took a shot at being independent producers with the ill-fated Bolivar in 1928. Over the next few years, Lantz took charge at Universal’s cartoon division and Colvig became his sound guru, inflecting the soundtracks with silly inventiveness and lots of clarinet.

For Colvig, his work at Universal became a springboard over to Disney, where he became a gagman and a sound artist extraordinaire, once leading the great composer Leopold Stokowski into bemusement by milking the most unusual noises from his beat-up old trombone. He was a singer, performer, and voice artist, always in service of comedy and searching for his next clever gag.

The era of sound film was a godsend for Colvig, literally allowing his voice to finally be heard. However, in the years before his Hollywood career, he was a silent film animator and cartoonist. As a sign of his interest in the possibilities enabled by new media, one of his comic strips was titled Life On the Radio Wave. The strip was about ways that people were reacting to having radio in their homes in the 1920s. One example showed two children skipping Sunday school, staying in bed listening to the preacher’s sermon on the dial instead. Another showed a man proposing, only to be foiled by a broadcast song lyric.

Colvig was a showman so even his signature on all those comic strips had a noticeable pizzazz. The loudest feature? That would be the big looping P at the front of Pinto. It was visually catchy and he had long signed it that way. When he worked at Disney in the 1930s, he was a bit of a larger-than-life figure among his peers. He was the voice of Goofy, for gawrsh sake! He also held distinctions such as ‘director’ of Mickey Mouse’s Cartoon Band, which may have been a one-time stint to play at a United Artists gathering at Mary Pickford’s Pickfair estate in June 1936.

So, although in Disney lore, it is artist Hank Porter who began signing the name Walt Disney with the distinctive looping D which remains to this day, there may be at least some reason to wonder if Porter wasn’t influenced by Pinto’s P. To bring that possibility into view, let’s look at some other clues.

So, although in Disney lore, it is artist Hank Porter who began signing the name Walt Disney with the distinctive looping D which remains to this day, there may be at least some reason to wonder if Porter wasn’t influenced by Pinto’s P. To bring that possibility into view, let’s look at some other clues.

First of all, the inked samples that exist by Disney’s own hand show that he did not actually sign his name in the manner of the iconic company ‘signature’ but that this was the result of chosen proxy signatories in the 1930s, namely Porter. It turns out that Porter was also a decent musician in his own right, handy on the ivory keys, and he was invited to join the in-house animation band, Firehouse Five Plus Two, but he declined. He started at Disney in 1936, which is arguably Colvig’s peak year—and also the year that Colvig directed the Mickey Mouse Cartoon Band. The photograph below shows the band mingling with United Artist partygoers, including Roy Disney, center left.

Given there was studio knowledge that Hank Porter could rattle a piano pretty well, it is certainly within reason that these two artists crossed paths, perhaps via a shared interest in playing music if nothing else. Regardless, Porter could easily have just admired the work of Pinto Colvig, the Clown Prince of the Disney Studio, or simply been aware of his work as a cartoonist, which he often just signed “Pinto” with the big looping P.

I realize that such a stylization need not be unique to Colvig. Another artist such as Porter might well have struck upon this same embellished letter treatment if left to his own devices, even if Colvig’s P predates Porter’s ‘Disney D’ by more than ten years. All these years later, the trail is surely too cold to confirm anything beyond the glimmer of conjecture or even to judge the degree that one’s P resembles the other’s D quite enough to really say there is a match.

For a blogger like myself, the thrill is always in the idea that one of my readers holds a parcel of knowledge that I don’t, that someone can fill in a blank or shine a light on the forgotten past. It is a popular perception that the Disney signate logo was actually Walt’s real signature, but like many things Disneyana, that perception was manufactured by the artists who rolled through his studio, some of whom went on to notable careers in comics. Considering the influence of Pinto Colvig at the studio in the 30s, we at least should slide this notion into the realm of the possible. If anyone has information to add, please comment below.

And as for Walter Lantz, what was the lasting impact that such tides and currents may have had on him? Of course, the success of Disney changed the very nature of his name. He had long gone casually by Walt, but Hollywood was too small a town for a pair of bigshot cartoon producers who liked to go by the same first name. In a short time, Lantz acquiesced to the Big D and history now remembers him as Walter, not Walt. And in time, he too used a signature as part of his company logo.

On March 13th, at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, there will be a Monday night 8pm screening of a restored print of Universal’s King of Jazz, which features a notable animated sequence produced by Walter Lantz. This feature film was scanned at 4K resolution and carefully restored and reconstructed last year by Universal, offering a remarkable opportunity to once again “see and hear King of Jazz in a form more faithful to its original length, running order and visual quality.” The film will be introduced by Peter Schade and Janice Simpson, who curated the restoration. If you’re in the L.A. area, join me there. Tickets are free by reservation.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Do we have an origin year for the Waltography font/logo? The earliest I could trace it back was 1955.

That photo of Walter Lantz reminds me of a scene in Abbott and Costello’s Universal movie IN SOCIETY. There’s a gag where Bud and Lou are inside of a moving van filled with furniture. If you look closely Bud Abbott is laying on the couch reading a Walter Lantz New Funnies comic book.

Kind of like a “Abbott and Costello Meet Walter Lantz” moment.

Yet another great Lantz post; thanks Tom.

I hope your Pinto Probe yields a pleasant surprise.

I’ve noticed that in the early films he was listed as “Walt Lantz” and later became known as “Walter Lantz.” I’ve always suspected that the reason was exactly the one given above. Thanks for the clarification.

I can add nothing here, except that I really hope that “KING OF JAZZ” makes it, fully restored, to DVD real soon, perhaps with some extra OSWALD cartoons of the period, beyond the titles already released to disk via the WOODY WOODPECKER AND FRIENDS collections, coordinated by Jerry Beck. I’d heard that the film was in the process of being restored, and I’m happy it is finally seeing its premier. This is terrific news!