Four years ago, when I published a journal article on the films that Shamus Culhane directed for Walter Lantz, I wrote in detail about his escalating use of modernist flourishes. It then turned into quite a wild ride, and I confess that I loved the attention, when this oddball story of what I’d found inside his cartoons became a front-page New York Times story (Arts section/April 11, 2011) and erupted into a short-lived media frenzy that resulted in interviews I gave to news outlets around the world.

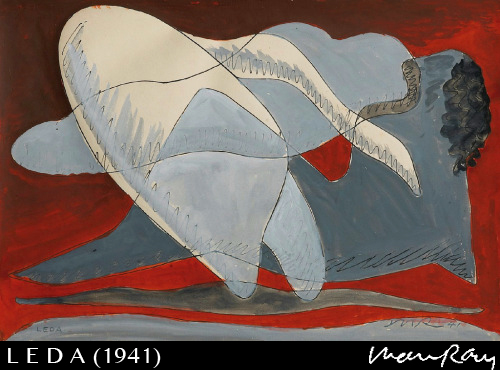

I was grateful for the overdue credit it gave to Shamus for parts of his work that had been overlooked and which surprisingly he had not discussed in his autobiography Talking Animals and Other People. Culhane in the 1940s certainly saw himself as an artiste and, in addition to wearing a beret on occasion, he increasingly used the Woody Woodpecker cartoons as his personal canvas to try out new things. No example is more vivid than this modern art painting—surely done by Culhane himself—which is featured within a flickering montage sequence.

I absolutely love this abstract painting that I like to call “Exploding Saturn” (1945). Unfortunately the original does not survive. However, by grabbing frames of the pan and assembling them, I’m able to reconstruct here what this image looked like. Culhane probably painted it in a hurry during a lunch break using staff artist Terry Lind’s brush and paints. He once described in a letter to me that he would work “in the background dept. over lunch hour because I wanted to avoid a controversy with a conventional background artist.” It was an experiment and in many ways this image can be seen as a product of a vibrant arts scene that took root in Hollywood during World War II.

Because of the huge dislocations of the war, traditional art enclaves like Paris were left behind and Los Angeles suddenly became home to quite a number of avant-garde notables in the early 40s. Americans were moving to L.A. too. There was definitely a westward magnetic pull. Alhough it was largely a cultural backwater relative to New York or Chicago, the good weather and allure of Hollywood apparently outweighed the drawbacks.

That there were so few cultural offerings in L.A. seems to have only galvanized this group of like-minded artists. Clara Grossman opened her American Contemporary Gallery in early 1943. When she began a weekly screening of films that she arranged on loan from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, she immediately drew an active and interesting crowd every Friday night. William Moritz wrote that “you might well sit next to D.W. Griffith or Lillian Gish or Man Ray or the Whitney brothers while watching a classic art film.” You were also possibly sitting next to Maya Deren, Oskar Fischinger, Jean Renoir, Slavko Vorkapich, Fritz Lang, Kenneth Anger, Billy Wilder, Jules Engel or Shamus Culhane.

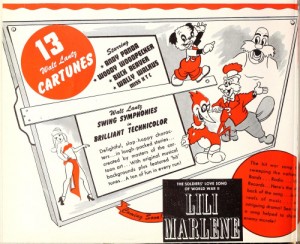

This August 1944 Lantz studio trade advertisement bills sexy “Miss X” as “Miss XTC” – and promotes a Swing Symphony based on “Lili Marlene” (which was never produced).

Walter Lantz Productions was on 861 Seward Street. The American Contemporary Gallery was on Hollywood Boulevard right near the classic Musso & Frank Grill. That means Culhane only needed to leave work and travel about ten blocks to make it to the evening screening. As shocking as this might sound to a Los Angeleno, he might have sometimes walked there. And from stories I hear, I bet he then had a drink at Musso & Frank’s with probably an interesting mix of Hollywood types and spillover from the gallery crowd. I wish Raymond Chandler had written about that.

These last few years in California have seen a concerted effort by the Getty Museums and Getty Institute to bring attention to the influential output of this art milieu that took root following the events of WWII. There is a beautiful coffee-table book, released in conjunction with Pacific Standard Time museum exhibits, that relates how in Los Angeles “the avant-garde film scene hovered at the edge of the city’s celebrated film industry.”

For me, I understand more clearly now how all of this connects within a rising Southern California zeitgeist. It is intriguing to look at Culhane’s experimentation as part of a bigger trend, especially in his first year at Lantz starting mid-1943. This was Culhane’s glory year, when he arrived fresh as a new director with huge ambitions and youthful reserves of energy. It’s during this year-long stretch that he did his best work, before the grinding hours needed to fulfill his ambitions started to drain him.

Shamus Culhane / Maya Deren

Her opening film credit notes the location as “Hollywood 1943” and in many ways that’s ironic. She went on to famously write a treatise named “Amateur vs. Professional” and Meshes is distinctly self-made and outside the mainstream. It invokes a mysticism that launched an expressionist genre known as ‘trance films’ that was later reinforced with the addition of Teijo Ito’s mesmerizing soundtrack. Meshes of the Afternoon is an anti-Hollywood movie. However, by tagging her film “Hollywood” was she lending it some Tinseltown glitz or was she punking the system?

Deren and Culhane moved in similar social circles and they were tapping into the same wells of inspiration. Around Christmas 1943, Culhane was working on Barber of Seville, his masterwork of comedic violence. There are qualities that his cartoon shares with Meshes. Culhane described how his approach to Barber was inspired by Russian film theorists. Deren, who grew up in a family of Russian-speaking Jewish intellectuals, would have certainly been aware of Eisenstein and Pudovkin’s films and published writings.

Both their films are striking for temporal distortions and daring edits. Both films are built around the narrative tension of a strange threatening character and the sight of a sharp weapon. In Deren’s film, which she also stars in, she is slowly pursued by a dark hooded character—is it the Grim Reaper? In Culhane’s cartoon, a guy is brutalized by an opera-singing redheaded maniac—that would be Woody Woodpecker!

Woody and Maya Deren with KNIVES!

Among the disturbing techniques used by both directors are the splitting of the main character into multiples. Maya Deren sits with herself at a table and we then realize we are seeing different versions of her throughout Meshes. Woody Woodpecker ends his aria in a weird visual crescendo where he splits into three, then four, then five woodpeckers. There is a deep sense of aggression in both these films that is then mitigated by their respective cinematic conceits: Meshes is not real, it’s a dreamlike trance, and Barber makes you laugh, it’s just a comedy. One is hypnotically slow and the other is rat-a-tat fast.

The Barber of Seville was released in 1944 and remains a classic of the Golden Age of American animation. Meshes of the Afternoon might be the most significant American film of its year, period. Think about it: 1943 is a weak year for cinema, not the least of which is obvious because the world was at war. Yet, 1941 gave us Citizen Kane and 1942 Casablanca. If there’s a live-action film from 1943 that truly flies in that orbit, please tell me, I haven’t seen it — and I think For Whom the Bell Tolls was a much better novel than movie, just saying.

The Barber of Seville was released in 1944 and remains a classic of the Golden Age of American animation. Meshes of the Afternoon might be the most significant American film of its year, period. Think about it: 1943 is a weak year for cinema, not the least of which is obvious because the world was at war. Yet, 1941 gave us Citizen Kane and 1942 Casablanca. If there’s a live-action film from 1943 that truly flies in that orbit, please tell me, I haven’t seen it — and I think For Whom the Bell Tolls was a much better novel than movie, just saying.

So I’ll be presumptuous and state that the best “Hollywood” film of 1943 was made over two and a half weeks without a shooting script by a maverick outsider named Maya Deren. To make this case, especially among our Cartoon Research crowd, I’m conveniently setting aside cartoons because we’re likely to show some bias, as much as we’re tempted to say Tex Avery had just as much influence or more than Deren with some of his 1943 MGM classics like Red Hot Riding Hood or Dumb Hounded.

I realize I’m making myself a perfect target for reasonable claims of overthinking. And we all know that this really does happen to pickle-brained academics. Like myself. But what if there is actually something to this zeitgeist or cosmic energy connecting a group of bohemian artists who flocked together in the 1940s. They created a burgeoning art scene that lived right on the fringes of Hollywood and slowly they began to change it.

What if Culhane saw an early screening of Meshes at Grossman’s gallery? What about the paintings there by Man Ray or Oskar Fischinger? It’s an amusing speculation, the details of which we can only wonder about now, but it’s fun to think how the cinematic DNA of this counterculture found such a perfect Hollywood insider to subvert mainstream cartoons, culminating in the subliminal modern art explosions of The Loose Nut.

I’m not a guy who believes in crystals or auras, but I do have an interesting final note about how truly karmic these connections can sometimes feel. Shortly after the New York Times article gave me fifteen minutes of fame, I was in my office relaxing in the wake of the media storm. Probably I was secretly fuming that the BBC and NPR no longer had a reason to call me. Then the phone rang and I smiled. Was it Brian Wiliams, NBC News? No, but it was a terrific colleague of mine, Matthew Fissinger. He’s the Director of Undergrad Admissions at LMU, where I teach.

He said to me, “You don’t know who I am” and I said “Matt, of course I know who you are.” Not only did I know him, but I was sitting at his former desk. The Admissions office had gotten a fancy remodel and he just moved to his new modern accommodations. I felt pretty lucky to inherit from him what I still regard as a very nice room with a picturesque window view of my campus. In fact, I had moved into Matt’s office only two months earlier.

He said, “My cousin is John Culhane, perhaps you’ve heard of him.” Of course I had. John was a renowned animation historian and I knew he’d been teaching at NYU for years. “John is Shamus Culhane’s cousin from the other side of his family.” There it was. I had been toiling at my Culhane research for years and had even traveled to New York to visit Shamus while he was still alive. Now I was sitting in the chair of a cousin of his cousin, and the universe was somehow connecting me back to him. Matt informed me that all the branches of the Culhane family had read the Times piece and loved it. It’s hard to express how gratifying and even vindicating that felt.

Just a week ago, on July 30th, John Culhane passed away at the age of 81. If there’s any fitting way to honor a guy who was a real champion for the finer art of animation, it’s to acknowledge how those Culhane men have gotten in my head and are still challenging me think about what makes cartoons tick. Rest in peace, John and Shamus. Here’s a toast to you both.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Because my story weaves around a three-year period, I just wanted to clarify the timeline, that Barber of Seville was released in 1944 and The Loose Nut in 1945. Also, Shamus Culhane recalls in his autobiography that Grossman opened her gallery in 1942, but other evidence and sources support that date as 1943, so I’ve used that date here.

Now you’re in my wheelhouse. “Barber of Seville” was one of the first cartoons I really studied, frame by fame, in the form of a silent black and white Castle Films 8mm print which I still own. I was ten, and I learned a lot. One thing that amazed me was how you could do violent, unhinged cartoon action on “twos” (that is, two frames per drawing) and make it look really good. I have decided that Shamus Culhane was the master of this, It flies in the face of what you’re supposed to do, but he did it and showed the way.

(I’m not suggesting he drew the whole thing, or any of it, but I bet, given the imperative to save time and money, he made sure that his team knew that energy must not and need not be sacrificed while incidentally saving Walt a bundle. Lots of subsequent Lantz cartoons did likewise; some of those dance sequences in “Abou Ben Boogie” go nuts with it.)

As for Mo-dren Art, those old Felix the Cats included some pretty experimental stuff, in particular when Felix was hitting the kangaroo juice.

I also had a silent 8mm Castle print of a Woody cartoon, but mine was “The Great Who-Dood-It” (retitled “The Great Magician”). Didn’t really learn much from it, though.

Weren’t many of the classic Warner cartoons done largely on twos?

Oh everybody used twos some of the time, but if handled badly it can look clumsy. I think people like Culhane figured out when you can do it, and when you shouldn’t, and it doesn’t necessarily follow any set logic: for instance, a character walking down the street at a measured pace almost always used ones; but you could do one of those free-for-all “fight balls” on twos.

Tom’s articles are fabulous. He could have saved himself the trouble of snipping together “The Loose Nut” painting because I did it in this post three years ago. It’s not the full thing but still a little longer than Tom’s version.

http://tralfaz.blogspot.com/2012/07/loose-nut-explosion.html

Thanks, and I’ve been to your Tralfaz blog many times, so I recall seeing this: thanks for stitching the pan BG to its full length, your version is better! Yes, it really does run to quite a length.

A wonderful piece. The Culhanes would be proud. Maya Deren might initially be surprised to see her work likened to THE LOOSE NUT, but after closely following Tom’s analysis, she would likely also be proud!

That ’44 Lantz trade ad actually seems to bill “Miss X” with the even sexier name “Miss XTC”!

Great article!

I hunger for more writing about animation like this: smart, informative, and devoid of fanboy obsessions. This is first-rate.

Enjoyed this piece very much and, though I’m very late to the party, I will look up a lot more info on Shamus & the LA art scene of the time. Thank you!