An animated Woody Woodpecker sequence in From The Earth to the Moon was perhaps just as much a reflection of the world in 1998—the year HBO released the miniseries—as it was a reenactment of the 1960s Space Race it purported to capture on film. The Woody that we see in this clip boldly vanquishes the Soviet moon effort and then plants the ‘Red, White and Blue’ on the lunar surface.

From that 1998 vantage point, our Cold War adversary seemed irrevocably beaten. The United States maintained an unwavering counterforce against the ambitions of Moscow for decades, with dissolution of the Soviet Union finalized in 1991. A vast militarized zone around Eastern Europe seemed to just shrink away, and the resolute stand of the United States was rewarded with a Russian fizzle instead of a fiery cataclysm.

From that 1998 vantage point, our Cold War adversary seemed irrevocably beaten. The United States maintained an unwavering counterforce against the ambitions of Moscow for decades, with dissolution of the Soviet Union finalized in 1991. A vast militarized zone around Eastern Europe seemed to just shrink away, and the resolute stand of the United States was rewarded with a Russian fizzle instead of a fiery cataclysm.

No one during the Cold War seriously imagined that the locked horns of the world’s two superpowers would end with anything less than a clash of armies or an exchange of powerful weapons. So the shock—and global relief—of such a placid ending was quite a tonic for our national mood. America was giddy with victory and a sense of being on the right side of history. The Eagle had triumphed over the Bear.

It’s interesting that Tom Hanks, the voice of Woody (Pixar’s Toy Story cowboy, that is), enlisted that other Woody to play the role of all-American cartoon champion in the miniseries; Hanks served as the show’s executive producer. Using the woodpecker’s appearance in the 1950 film Destination Moon as inspiration, the creative team turbocharged Woody with a winner’s zeal, a confidence that spoke volumes about the 1998 American worldview.

The sequence that plays within From the Earth to the Moon is historical fabrication, a teasing bit of Cold War jingoism. Yet it doesn’t seem entirely out-of-character either. The brash aggression of Woody was unleashed on many other targets over the years, so he was easily re-imagined here as a Cold War crusader who aims his beak against cosmonauts, though mostly he jokes around. It’s certainly not the Woody of the Culhane years—too criminally insane to be a loyalist of anything—but let’s not forget that Woody by 1960 was not the same bird anymore. Somehow by the Sixties he had become more conformist, less deviant.

The sequence that plays within From the Earth to the Moon is historical fabrication, a teasing bit of Cold War jingoism. Yet it doesn’t seem entirely out-of-character either. The brash aggression of Woody was unleashed on many other targets over the years, so he was easily re-imagined here as a Cold War crusader who aims his beak against cosmonauts, though mostly he jokes around. It’s certainly not the Woody of the Culhane years—too criminally insane to be a loyalist of anything—but let’s not forget that Woody by 1960 was not the same bird anymore. Somehow by the Sixties he had become more conformist, less deviant.

This might be seen as negating his more subversive past. Under Culhane, the musical montage of those violent Woody numbers was built on the foundation of Sergei Eisenstein film theories. Woody could kick-dance like a Cossack peasant and he could sing lyrics in perfect Russian. But he was always a patriot. In World War II, Walter Lantz employed the woodpecker to be a mascot for a number of military purposes. Woody was an ambassador of goodwill. And a badass, too.

One lasting pernicious effect of America’s wartime alliance with the Soviets was that it seduced some pro-labor activists to easily liken a Soviet agenda to their cause, seeing that Uncle Sam momentarily encouraged this sentiment. For some that sympathy may have been intentional, but for many others it was a consequence of simply having left-wing political beliefs that ignited into post-war infamy. Suddenly they might be accused of being a red or a commie, even if they were little more than the equivalent of modern-day Bernie Sanders supporter.

I bring this up as a way to seek answers for one of the larger mysteries behind the Woody Woodpecker & The Avant-Garde exhibit. There is evidence of the important role that the historic American Contemporary Gallery played in Los Angeles, yet if that’s the case—if this venue does deserve our attention—then why has it so thoroughly slipped off the cultural map? Why has no one heard of it?The answer may have something to do with the gallery’s public embrace of that very Soviet brand of communism, including an exhibit of constructivist WWII posters provided by the Soviet news agency Tass. This was all done under the approving eye of the U.S. government during the war, but afterward it may have lingered as an unseemly association.

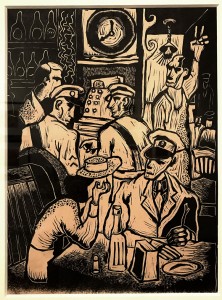

In fact, one artist stands out among others for having been exhibited at ACG at least five separate times, from 1943 on, making him something of a gallery favorite. He was Byron Randall, an unapologetic communist who often painted pictures of everyday people. During his service as a merchant marine in the Pacific, he painted the people and colors of New Guinea. As an artist whose work was on frequent display at ACG, Randall’s mix of artistic talent and social activism probably helped to lend this gallery its political bent.

I imagine this was exactly the sort of place that would later be branded with derision as a “hotbed” of political extremists during the McCarthy era. Which leads me to speculate about its disappearing act: though I still have no direct indication this was the case, one could easily reason that in the post-war political climate there may have been some necessity to conveniently “forget” about the gallery and its patrons. And to “deny” that one had ever been there personally.

Byron Randall and his wife felt the need to leave the U.S. and they relocated to Canada in 1953 in light of government suspicion of their political sympathies. The American Contemporary Gallery closed by 1949 and very little has been written about it subsequently. Because ACG left such a big impression on Shamus Culhane, he wrote about it effusively in his autobiography.

Byron Randall “Cityscape Of New Guinea” (1944)

With the current Laband gallery exhibit, which is only open for one more month, one of my goals has been to have Woody plant another flag, just like the one on the moon, a long-delayed gesture to make light of something that had actually happened long before. The intersection of cartoons and the avant-garde in the 1940s was about much more than politics, but an observer sees how this played a role.

The intention of American Contemporary’s founder Clara Grossman was not to foster a gathering of communists, though the gallery surely leaned left. Avant-gardists were interested in shaking up conventions and provoking viewers to think, not to create conformity to one form of counter-thought. With a visit to my exhibit, seeing the many painters, filmmakers and animators who congregated there to share an impressive body of collective work, you too can judge for yourself the legacy of art, cinema, modernism and politics that ACG left behind.

Woody Woodpecker & The Avant Garde is open from September 22 to November 20. Admission to the Laband Art Gallery is free. Open Wednesday through Sunday, noon to 4:00. The works of art on display from Byron Randall are the first gallery exhibition of his work in the United States in several decades.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Sad there’s no clip from the miniseries. That would be a treat to watch….

Unfortunately is not available online, and to my knowledge HBO has not offered it streaming yet through HBO Go or HBO Now. If that changes, I’ll let you know. In Episode 1, you will find one sequence of an animated film being shown to schoolchildren where Woody and Chilly demonstrate “extravehicular activity,” a spacewalk in a spacesuit. Then, in another sequence set during a fundraiser/pancake breakfast in Shreveport, Louisiana (coincidentally La Verne Harding’s hometown), a crowd cuts it up watching this: Woody jets away on a rocket, leaving a wolf cosmonaut behind with his rocket disintegrated, and the Soviet hammer & sickle drops off and sticks into the moon. Then, after Woody sticks the American flag in the ground, he demonstrates another sequence of how the lander launches off the moon surface to reconnect with the lunar orbiter.

Could you possibly do an article about Walter Greene’s and Darrell Calker’s cues originally composed for Lantz being used as stock music?

Thanks for the suggestion, Evan. I also wanted to wonder out-loud if this wouldn’t also make a terrific post from James Parten, my terrific new fellow columnist, who writes those Needle Drop Notes. He possible knows more about this than i do.

I’ve been looking through the first episode of the miniseries from HBO Max and cannot find the Woody Woodpecker scene! Did the HBO Max version took it out or something? Please, give me the exact moment where it has it!