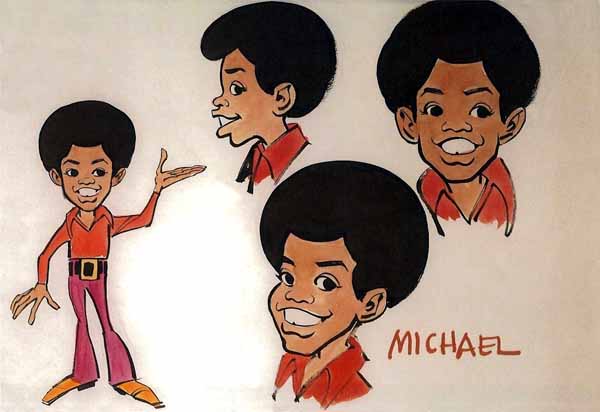

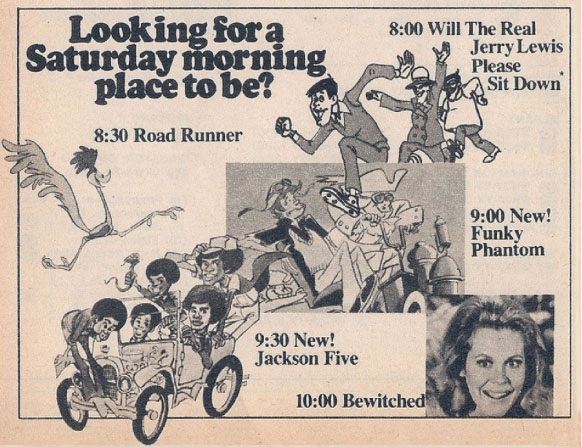

In 1971, when Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass contracted with Motown Recording Company to produce an animated Saturday morning television series caricaturing the recording group the Jackson Five, they capitalized on the group’s popularity. The R&B group’s first four singles for Motown topped the pop charts, and the popularity of the music and the young ages of the members (from 13-year-old Michael to 20-year-old Jackie) made them ripe for weekend cartoon fare. Rankin-Bass hired African American actors to voice the group’s speaking lines, and veteran actor Paul Frees voiced incidental characters. Mad magazine cartoonist Jack Davis created the model sheets and established the character designs. In a rare bit of 1970s vocal cultural appropriation, Frees even voiced Motown’s African American founder Berry Gordy, which at least improved upon his voicing of the slave Uncle Tom in Tex Avery’s 1947 cartoon Uncle Tom’s Cabana for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

The Jackson Five tried to attract viewers to music as well as to the half-hour stories. Each episode of the 1971-72 season featured two recordings from the group’s albums (Diana Ross Presents the Jackson Five, ABC, Maybe Tomorrow, and Third Album).

The Jackson Five tried to attract viewers to music as well as to the half-hour stories. Each episode of the 1971-72 season featured two recordings from the group’s albums (Diana Ross Presents the Jackson Five, ABC, Maybe Tomorrow, and Third Album).

For the music sequences, Robert Balser incorporated psychedelic animation reminiscent of his work on the Beatles’ animated feature Yellow Submarine. Rankin-Bass could not possibly have known that the studio was producing a time capsule of a transitional period for Motown. When the series began on September 11, 1971, Motown was headquartered in Detroit, where it had been since its founding in 1959. The company frequently achieved top-ten pop hits by the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, the Jackson Five, and others. However, in June 1972, Motown suddenly announced that it was relocating to Los Angeles. The company had another recording studio there, and Gordy was making a biopic feature for Paramount Pictures about singer Billie Holiday.

The most popular soloists and groups for the company were invited to go west, but the lesser-known and fading stars and the phenomenal in-house musicians known as the Funk Brothers stayed behind in Detroit. Motown kept its Detroit facility open for two more years for those left behind before fully becoming a Los Angeles-based company. The Jackson Five survived the relocation to California, but the group’s music never sounded the same. After all, they did not perform their own instruments on their recordings, despite the frequently reused animation of Tito and Jermaine playing guitar on the show. As a result, the seventeen episodes comprising the 1971-72 season capture the last days of Motown-Detroit in animation.

The series returned for the 1972-73 season with six more new episodes and a different title: The New Jackson 5ive Show. The animation was of poorer quality. At the time Rankin-Bass was producing full seasons of new series Kid Power and The Osmonds.

Also, with recording activity slowed, the studio had only two new albums of recordings to mine for the episodes. One of the albums was not even by the group but rather Michael Jackson’s first solo effort Got to Be There. The other album Looking Through the Windows did not sell as well as the group’s previous releases.

The rest of the episodes that season were reruns, and the music on them sounded dated by 1972. R&B was changing, and the mixture of soul and “bubblegum” that had carried the group since 1969 was not as popular as the lush orchestrations of Philadelphia-based R&B recordings like the O’Jays’ “Love Train” or “Betcha By Golly Wow” by the Stylistics. Meanwhile, R&B sounds also became more psychedelic through Motown’s albums by producer Norman Whitfield and through non-Motown groups like Sly and the Family Stone. A new album by the Jackson Five (Skywriter) was released during the 1972-73 season of the show and fared even worse than Looking Through the Windows.

The rest of the episodes that season were reruns, and the music on them sounded dated by 1972. R&B was changing, and the mixture of soul and “bubblegum” that had carried the group since 1969 was not as popular as the lush orchestrations of Philadelphia-based R&B recordings like the O’Jays’ “Love Train” or “Betcha By Golly Wow” by the Stylistics. Meanwhile, R&B sounds also became more psychedelic through Motown’s albums by producer Norman Whitfield and through non-Motown groups like Sly and the Family Stone. A new album by the Jackson Five (Skywriter) was released during the 1972-73 season of the show and fared even worse than Looking Through the Windows.

The new release listed Motown’s address as Los Angeles. A few days before the series ended on September 1st, 1973, the Jackson Five released the single “Get It Together”. It moved away from bubblegum-soul and towards psychedelic soul. Motown released the album Get It Together in September, and the following spring it yielded the early disco hit “Dancing Machine.” The hit single came too late for the series and, thus, never received any animated treatment. Then again, the new song had a mature sound, and The Jackson Five had done its job of promoting the last of “The Sound of Young America.”

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

It’s too bad there couldn’t been a Supremes cartoon had Florence Ballard not been left (or before that). Just think of all the goofy situations they could have been into for a cartoon! Also, Steve Stanchfield wanted a Four Tops cartoon as well.

The Jackson 5 may have been the best fit, but it has much left to be desired for some.

Also the Blu-ray has some of the worst DVNR I have ever seen in a Blu-ray set, I just had to stop the binge watching. I wish a Jerry Beck or a Steve Stanchfield could consult on the cleanup for 8k for Universal.

Diana Ross voiced an animated version of herself in the first J5 ep, “It All Started With…”

Great animation imported from the Yellow Submarine Nation itself and Halas-Batchelor in this one. Too bad the gags and story are a rehash of tired material spanning too many decades past. How many times have we seen a cartoon character or live-action comedy star “get through” an entrance with a guard? (The Muppets in their first feature getting past Cloris Leachman was arguably the best of the lot. Plus it got the gag done in less than two minutes!)

Well the character development of Ralph the Guard from Tiny Toon Adventures made him the “Elmer Fudd” for Yakko, Wakko and Dot in Animaniacs.

I can’t believe you thought today was an appropriate day to post this.

Thought so too.

Many of our regular contributors submit their Cartoon Research articles days, weeks, even months in advance. It’s quite a coincidence Michael Jackson happens to be in today’s news. That said, this is an animation history website. We cover the art form, the people, the films and series created irregardless of current day events. To ignore or bury any part of that would be doing a disservice to our readers – and to our mission to provide information in service of the history of animation.

Jerry, it’s your site, you can do whatever you want. But Jackson, the star of this cartoon, is a real person and he isn’t just in the news— there’s a huge documentary out right now about how he raped at least two children over the course of years. I don’t think you should have killed this story, I just think you should consider waiting a month or two to talk about a kids cartoon by a person who would go on to rape kids.

As Jerry noted, I wrote this essay weeks ago. But the point of my essay was not about Michael but rather about the Motown label, and my argument is that this cartoon is a time capsule for Motown’s transition from Detroit to LA in 1972. At that time Michael Jackson himself was a child and at least fifteen years away from the allegations that the “Neverland” documentary chronicles. As for the Jackson Five music, the Jacksons only sang it. Motown staffers composed all the songs, and session musicians played the instruments. So Motown rakes in the money from the music’s exposure. And, as I mentioned, Jackson’s career was in decline by 1972 and didn’t fully rebound until “Off the Wall” in 1979 and, of course, “Thriller” in 1982. So at the time of the cartoon, Jackson was not the phenomenon that he later became as an adult, and “Neverland” strictly talks about Jackson’s influence after he became that phenomenon in the 1980s.

Michael Jackson did nothing wrong.

I would side with Lehman on this as well, he was writing about Motown and it’s Detroit origins itself. I could see the significance brought up in it’s transition from it’s former home to LA, and not doubt this cartoon came out at an interesting crossroads for the record company.

Christopher (the writer of this article. I can’t belive there are three Chris commenters in this thread)— You wrote a great article, and the Motown machine is endlessly fascinating. The amazing art it produced vs how it treated its artists is something I could read about forever. Maybe I’m saying this because I just watched four hours of Leaving Neverland and the pain Jackson caused is fresh in my mind, but I’m just asking that this article be released on a different day. Do it next month. Do it two weeks from now. It’s like the Jackson estate releasing those concert films on YouTube the same day as the documentary’s initial airing— a potential distraction that, because of its specific release, becomes an implicit show of support. I don’t think you support what he did. Maybe you don’t think he did it. Either way, I’m not arguing this was intentional. I’m just saying “you could have held the article a couple weeks.”

Thanks for your kind words about my essay. I believe that the allegations in “Neverland” could quite possibly be true; I have no reason to dismiss them. For me, Jackson’s reputation was badly tarnished after the early 1990s, and “Neverland” just made it irreversible.

I definitely understand your point about the timing of yesterday’s essay, but, having not seen “Neverland” before writing my essay, I had no way of knowing how powerful the content would be; and I agree that it is powerful indeed. Also, I do not determine when my essays are posted; I just write them.

On a side note, Motown music’s history in animation predates the Jackson Five cartoon. I vividly remember one of the sing-alongs in the Beatles cartoon being the group’s cover of the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman.”

Guess we won’t be covering FAT ALBERT AND THE COSBY KIDS any time soon. Not that the problem there involves “kids”.

“In a rare bit of 1970s vocal cultural appropriation, Frees even voiced Motown’s African American founder Berry Gordy, which at least improved upon his voicing of the slave Uncle Tom in Tex Avery’s 1947 cartoon Uncle Tom’s Cabana for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.”

I didn’t realize that was Frees in that Avery short. Was “Cabana” the first cartoon Frees did a voice in? He eventually was a frequent player in Avery’s MGM shorts including his last one “Cellbound”.

According to imdb.com, Frees’s first voice-cartoon role was in Columbia’s”A Hollywood Detour” (1942), directed by Frank Tashlin.

Some songs that were used, one of them was from Greatest Hits and one was only a B-Side single. Those were also from the second season.

Thanks for catching that, Patrick.

Speaking of the Osmonds, boy, were Rankin-Bass sure lucky to hire all six performing Osmond brothers to provide their own speaking voices. And you had to hear Donny’s voice maturing, even when he spoke.

I enjoyed this article as I remember this show when it first aired on Saturday mornings. It is also worth noting that this was the first animated series to have African-Americans in the starring role; if my memory serves me correctly. There was a lot of hoopla when JULIA debuted on NBC in 1968 as the first TV series to have an African-American in the lead role; it was a live action series with Diahann Carroll playing the lead role. Bill Cosby would get the first of his TV shows in 1969 with THE BILL COSBY SHOW on NBC. FAT ALBERT AND THE COSBY KIDS would not enter Saturday mornings on CBS until 1972 so THE JACKSON 5IVE was the first animated series to star African-Americans in 1971. With the introduction of THE JACKSON 5IVE in 1971 and then FAT ALBERT in 1972, the doors opened up on Saturday mornings for more shows with people from different ethnic backgrounds.

Is that a Jack Davis model sheet?

Yes, Jack Davis designed the characters.

I was 10 when this was on and I was impressed that Jackson 5 had a cartoon show just like the Beatles had. Big league! We loved the Harlem Globetrotters and Fat Albert, too. Jackson 5 had records on the side of the cereal box. I was impressed!

My intro to the group. At 9 and 10 years old, shows like this and the Harlem Globetrotters that were based on real people, I took as biopics lol.

Had a friend who, when he first saw the J5 as a guest on some show was surprised that they were really a group.