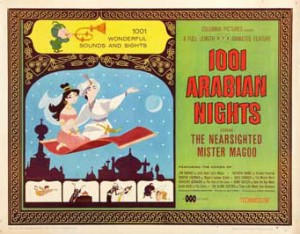

By December 1959 the cartoon studio United Productions of America (UPA) had almost completely lost the collective personality it had cultivated in its one and one-half decades of existence. Of the original staff, only Steve Bosustow, who had served since the beginning as executive producer, remained at the studio at the time. His colleagues had left, one by one, either through resignations or firings. Meanwhile, Columbia Pictures stopped distributing UPA’s films to theaters. The distributor’s last commitment to the studio was the release that December of the feature 1001 Arabian Nights, which stars UPA’s marquee character Mister Magoo. One of the promotional efforts from UPA for the film demonstrated that the studio’s internal dissolution changed its politics about ethnicity.

Bosustow promoted the movie in New Orleans by giving a talk at Tulane University on December 11th, 1959. The school’s Fine Arts Committee hosted the lecture, in which he spoke about the creative process of animation. He noted that cartoonists introduce story ideas to their psychiatrists, discussed the weaving together of animation and psychology, and stressed the importance of strong plots to cartoons regardless of their aesthetics. According to the New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper of December 12, he likened the contemporary cartoon’s story to a “one-act play.” Thus, stories, especially for cartoon shorts, had to be “solid.”

Bosustow promoted the movie in New Orleans by giving a talk at Tulane University on December 11th, 1959. The school’s Fine Arts Committee hosted the lecture, in which he spoke about the creative process of animation. He noted that cartoonists introduce story ideas to their psychiatrists, discussed the weaving together of animation and psychology, and stressed the importance of strong plots to cartoons regardless of their aesthetics. According to the New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper of December 12, he likened the contemporary cartoon’s story to a “one-act play.” Thus, stories, especially for cartoon shorts, had to be “solid.”

At the time Tulane University was a “whites only” institution. The school opened Bosustow’s lecture to the general public, but none of Tulane’s students in attendance were African Americans. Consequently, Bosustow’s speech in a segregated facility represented a 180-degree turn from UPA’s roots in challenging Jim Crow. The studio depicted segregation as the rickety train “Jim Crow Special” in its 1944 cartoon Hell-Bent for Election. Two years later UPA argued for “equal opportunity” and an “equal chance for a job” in Brotherhood of Man, and it illustrated scenes of integrated hospitals and neighborhoods to punctuate its points.

Ironically, the Orpheum–the theater premiering the movie in New Orleans–allowed African American customers but restricted them to balcony seating. Neither UPA, Columbia, or Bosustow provided a comparable promotional event at a location of exclusively or primarily African American patronage. By speaking only in a “whites only” institution, Bosustow tacitly suggested that he prioritized attracting European American customers to watch his film. Whether African Americans saw the feature at inconvenient seats in the Orpheum or did not see the film at all appeared inconsequential to him and to his studio and distributor.

Ironically, the Orpheum–the theater premiering the movie in New Orleans–allowed African American customers but restricted them to balcony seating. Neither UPA, Columbia, or Bosustow provided a comparable promotional event at a location of exclusively or primarily African American patronage. By speaking only in a “whites only” institution, Bosustow tacitly suggested that he prioritized attracting European American customers to watch his film. Whether African Americans saw the feature at inconvenient seats in the Orpheum or did not see the film at all appeared inconsequential to him and to his studio and distributor.

Ultimately, his pitch to European Americans did not help matters. 1001 Arabian Nights generated a lukewarm theatrical attendance, and critics offered mixed reviews. Within days of the movie’s debut, according to Adam Abraham’s book When Magoo Flew, Bosustow began seeking a buyer of his share of the studio. In the final days of UPA’s theatrical era, the studio compromised its ideological commitment to integration to keep itself afloat. At the expense of African Americans, Bosustow gambled–and lost.

The Orpheum Theatre in New Orleans in 1955 (playing an earlier film starring Kathryn Grant – the voice of Princess Yasminda in UPA’s “1001 Arabian Nights”)

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Well, I wouldn’t say that UPA “changed its policy” and sold itself out to Jim Crow. Steve just happened to be speaking at a school that taught fine art that just happened to be whites-only; I’m sure no prejudices were in his decision.

I don’t say UPA “changed its policy” either, but rather its “politics” changed. I don’t know that Bosustow could have “just happened” to speak at a segregated facility. In all my years of giving speeches from time to time, I’ve never “just happened” to give them; my speaking venues were always deliberate choices. Also, Bosustow wasn’t ignorant of “Jim Crow;” after all, he produced two cartoons that specifically challenged it. He had his reasons for going to Tulane, and I don’t know what they are. The end result is that the former producer of pro-integration cartoons spoke at a segregated institution.

This is an important perspective to know about. Thanks for sharing this information. While UPA’s leadership and staff may or may not have had elitist intentions, the attitudes of the time were systemically ingrained, almost to the point of universal acceptance–or perhaps to just “not giving it much thought.” So while the exclusion may not have been deliberate, its outcome was still of a biased nature.

I’m glad we live in a time when I can go to the movies with my friends, who are of many diverse races, and we don’t have to go to separate movie houses. I value all of my friends highly, and would not have had the rich experiences that I have if I had lived in those less enlightened times.

It’s also unfortunate that this film performed so poorly at the box office–beyond that, it’s unfortunate that in the first place, it was so poorly made. While I “like” this film and am a big fan of Mr. Magoo, the pacing is slow, the characters are underdeveloped, and the dialogue is weak. Yet some of the best talent of its day went into the making of this film–fine actors, and overall decent animation. I love the songs, particularly “You Are My Dream.” (incidentally, this song plays as background music in the movie “Pepe” which was released in 1960.) This seems to prove that even with top talent all around, it’s not a guarantee of a quality product. I guess it took 30-plus more years for Disney to do better animated justice to the “Aladdin” story.

This is a rather gray area that is still interesting to debate and discuss, especially since UPA was very progressive during its early years. After all, you didn’t see the Disney studio making films like BROTHERHOOD OF MAN. One wonders if John Hubley would have said something about this had he still been on the payroll. Then again, he was among those not belonging to McCarthy’s America and UPA certainly had plenty of trouble there earlier in the decade.

It definitely ate away at them. We went from the promise that Brotherhood of Man had to eventually seeing an Asian American stuck in a servant role for Magoo during the TV era.

Perhaps it was when Henry Saperstein took over UPA and turned it into another TV cartoon factory that things started to change – aside from Magoo’s servant, there were also Joe Jitsu and Go Go Gomez in the Dick Tracy series, who were among many silly characters that were never in the comic strip.

It makes it all the more interesting when it’s looking into UPA’s future under Saperstein, who made deals to produce several movies with the famous Japanese studio Toho, resulting in getting exclusive rights to several key Godzilla titles for decades to come.

The thing about Hell Bent for Election that always made me shake my head was that the cartoon shows the Jim Crow Special on the *Republican* train. Granted that there were racial issues in the North, and Northeast, but even still, that took some chutzpah to apply the term Jim Crow in favour of a party whose power base depended on the suppression of African-Americans.

Right? Considering the Democratic Party in the 1940s depended on that bastion of Civil Liberties the Solid South.

If UPA insisted that the stories in its cartoon shorts “had to be solid,” one wonders how that description could apply to “The Rise of Duton Lang,” despite having been based on a magazine article.

It was rather pretty far-reaching to simply go with a magazine article that probably never saw a reprint in any other form later on.

Makes me think of the way the animated film of FINIAN’S RAINBOW was cancelled because of Hubley’s(and Yip Harburg’s) involvement in it.

Can’t help thinking that Bosoustow was just worn out after all those years.

Is it fair to blame Mr. Bosoustow for accepting a speaking engagement connected to his producing a film that might have enlightened and influenced a segregated audience? He had no control over who attended. And the fact that any university gave credence to an animated film, seeing it worthy of recognition is a credit to the work and the producer of that work.

Social change was slow to happen back then. But it seems that greater progress was made 60 years ago compared to the way we have rapid regression we are seeing today. So we really need to see where we are now, consider what was done before as examples, and build on that to move the agenda forward once again.