The abandonment of the animated feature film after 1918 did not mean that Argentine cinematography quit making cartoons. Throughout the 1920s, producer Federico Valle continued to include animated fragments in his weekly newsreel, some of which were made by Cristiani, while others came signed by cartoonists such as “Moglia” (Luis Moglia Barth, an assistant to Cristiani who would later become a key figure in Argentine cinema directing Tango, Argentina’s first feature film with optical sound and “smash hit” from 1933); or by Carlos Wiedner, a German artist who worked for many years producing naturalistic animal prints for children magazine Billiken.

“Los que ligan”, short film by Quirino Cristiani created for Cinematográfica Valle (1919).

“Fragmentos Cristiani”, animated segments for Cinematográfica Valle’s newsreel, around 1922. Despite the title, only the last of these shorts belongs to Cristiani. The difference in style between cartoonists is remarkable.

Another example of the animated productions created for Cinematográfica Valle in 1922. The first fragment is drawn by Luis Moglia Barth:

According to Peña, more consistent seems to have been the production of Romeo Borghini (or Borgini), who used techniques similar to those of Cristiani, but interspersed with fragments of newsreels. A surviving copy of Borghini’s short film Del Puerto de Palos al Plata (1926), about the crossing of the Atlantic by the aviator Ramón Franco, was recently discovered.

An even stranger story is the one that seems to have linked Andrés Ducaud with the film producer Rafael Parodi, owner of “Tylca Films”. As can be extracted from a certain booklet entitled Jurisprudencia Argentina, 1923: “On June 1, 1923 Cristiani accused Parodi and Ducaud for forgery of a patent of invention, requesting that they be sentenced to the “maximum” of the penalty established in article 53 of law number 111.” It is not known whether Ducaud and Parodi ever produced any films, but this story suggests that relations between the animators were more strained than might be supposed.

Fragments from the same group photo. On the left, Ducaud. Right, Rafael Parodi.

Peludópolis or the beginning of the end

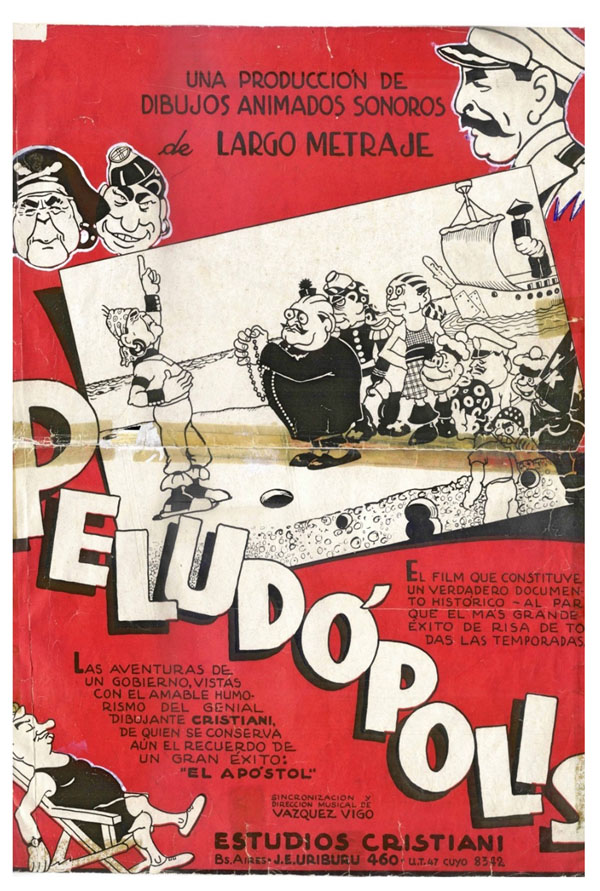

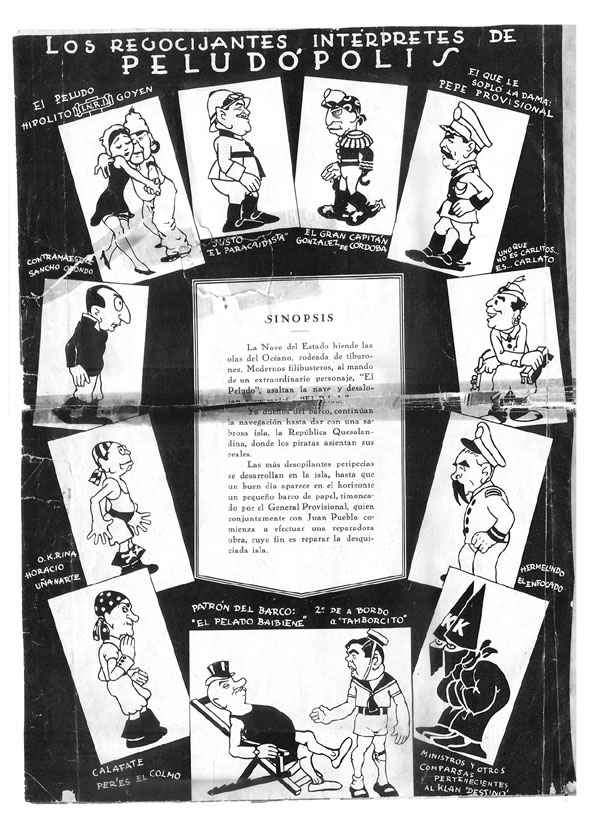

“Peludópolis” movie ad.

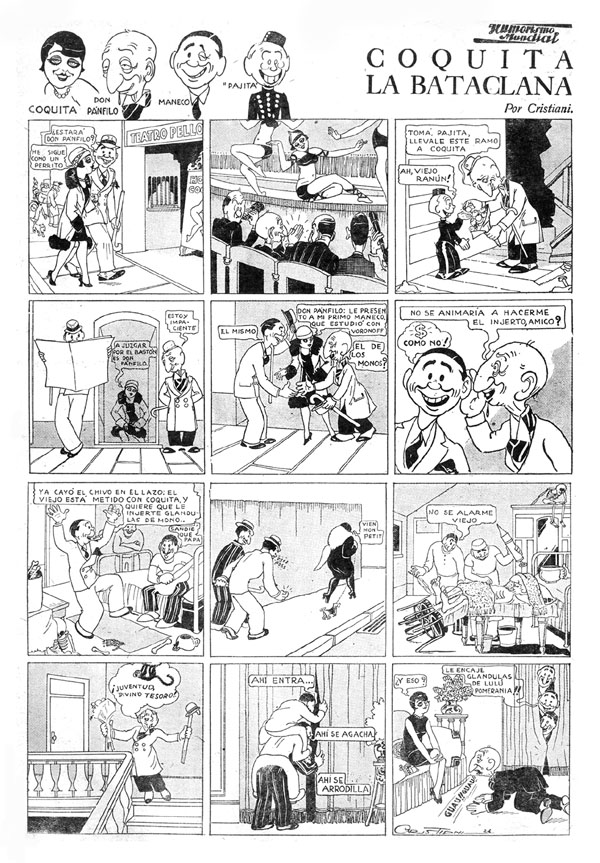

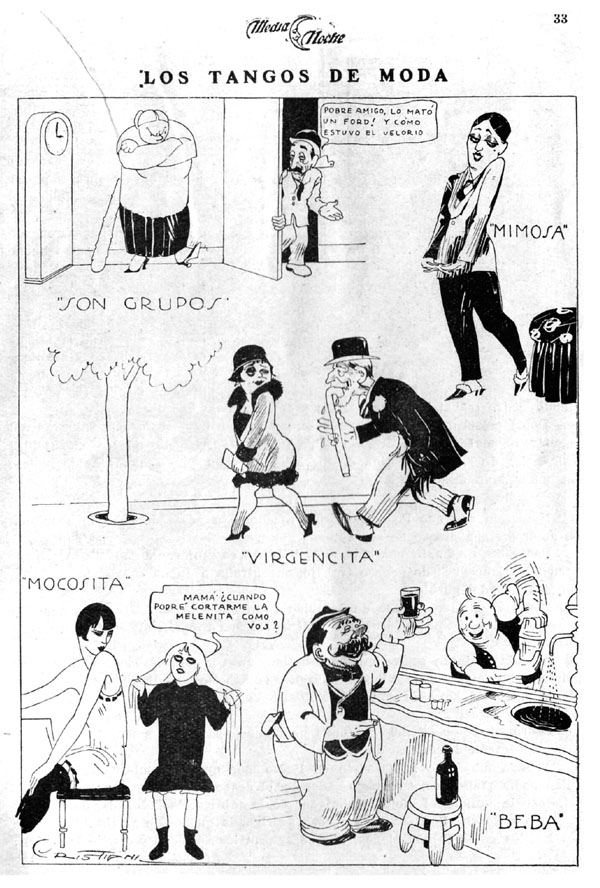

Quirino Cristiani’s work was not limited to a few excerpts, produced for Valle, or a couple of animated shorts on topical humorous themes, which he released on his own. Throughout the 1920s he continued to be a regular contributor to Buenos Aires’ publications (generally picaresque in tone) such as El Magazine, Última Hora, Caricatura Universal, Humorismo Mundial, Media Noche.

ABOVE: Cristiani’s page of “Coquita la Bataclana”, “Humorismo Mundial” magazine, 1926

ABOVE: Cristiani’s page of “Los Tangos de Moda”, “Media Noche” magazine, 1926.

At the same time, he implemented a bizarre street advertising service. Cristiani tells Bendazzi:

“I contacted the owner of a cloth factory who loved the cinema. The idea was to offer to show free films to the public on the street, with a “movie-truck” that would show short films with animated advertising as interludes. He was to finance the project. (…) To start with, we decided to do a three minute animated drawing with an advertising message, and then present it to a few possible clients to see if they were interested. (…) So I made Las aventuras de Fosforito (The Adventures of the Match Man)”.

The results were excellent. They bought the truck, and made it into a luxury mobile cinema equipped with a projector, accumulators, and a dismountable screen. The films were back projected: the machine was behind the screen instead of behind the audience. The driver and his helper were responsible for the show, so one ran the projector, whereas the other entertained the audience as “speaker” (the films were silent). Eventually, the venture fell victim to its own success. Because of the crowds it caused, street exhibitions were banned in the city.

In 1927 Quirino Cristiani was named art director of Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer’s advertising service in Argentina. His job was to create posters that would be placed on the streets to announce the arrival of a new movie from Hollywood’s largest producer. This new volume of work made it impossible to continue contributing to publications. Therefore, Cristiani’s journalistic career ended.

At last, in 1928, he opened the “Estudios Cristiani”. The head of MGM in Argentina was accommodating with respect to his art director’s second job, and entrusted him with the task of using his equipment for animated films to prepare Spanish subtitles for the imported American films. This collaboration between the “Estudios Cristiani” and MGM turned out to be essential over for the artist on the following years.

Movie poster of “Peludópolis”.

1928 was also the year in which Yrigoyen, the protagonist of El apóstol, returned to the presidency, and Cristiani felt that this return could also be his own: together with a small team, he began to work on a new project, based on a subject written by Eduardo González Lanuza and titled Peludópolis (“Peludo” -the armadillo- was Yrigoyen’s nickname).

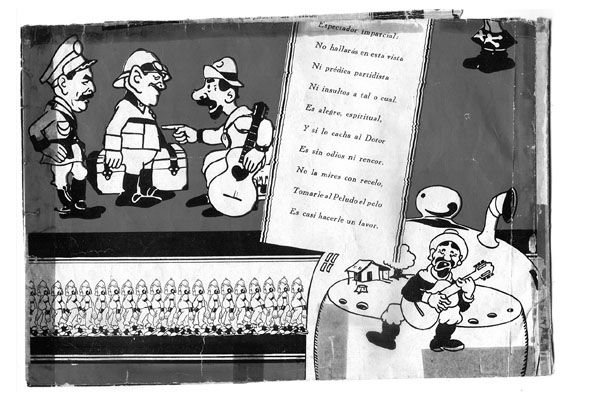

“Peludópolis” poster’s back.

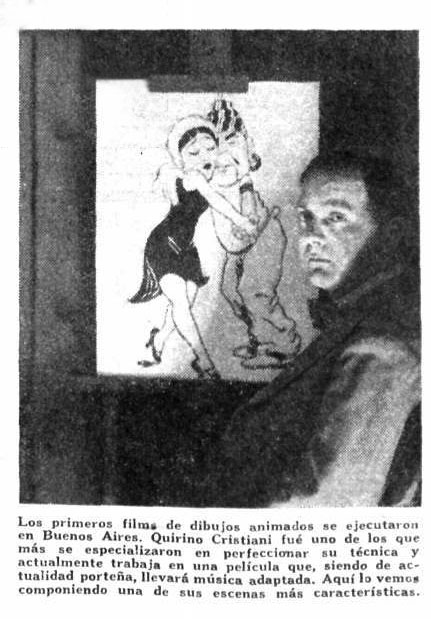

Cristiani did everything himself for this third feature. He created and designed the characters, animated, directed and produced. He had several helpers, but he was not obliged to accept any suggestions about creative aspects.

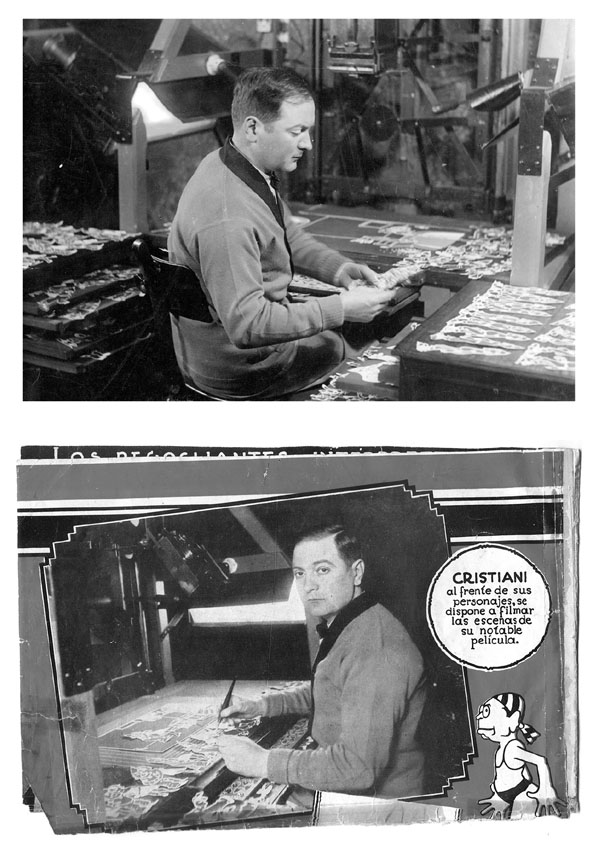

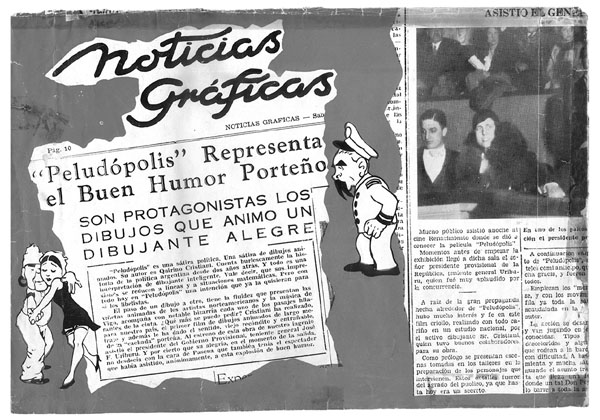

“Peludópolis” in the making, advertising article.

However, the Peludo did not stay in the Casa Rosada (Argentina’s equivalent to the White House) long enough to allow the satirical film to be completed as originally planned. On September 6, 1930 the revolución led by General José Félix Uriburu removed him from office. The first animated feature sound film had coincided with the first Argentine military takeover.

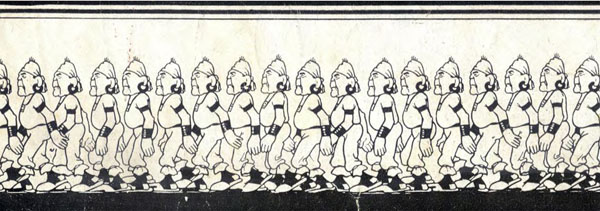

The change of political scenario forced Cristiani to redo his project. In the final version, the plot can be summarized as follows: The Government ship sails across the waves, surrounded by sharks. A few modern pirates, led by an extraordinary character, “El Peludo,” attack the ship and drive away its captain, “El Pelado” (“Baldy”, a nickname for Alvear, Yrigoyen’s predecessor and leader of an opposing faction within his own party). Now in command of the ship, the pirates continue sailing until they reach a tasty island, the “República Quesolandina” (the Republic of Cheeseland). They have hilarious adventures there, until a paper boat appears on the horizon. Its captain is the “General Provisional,” (none other than Uriburu himself) who along with “Juan Pueblo,” (“John People”, an argentine version of John Q. Public) begins to work on repairing things, with the ultimate goal of restoring order.

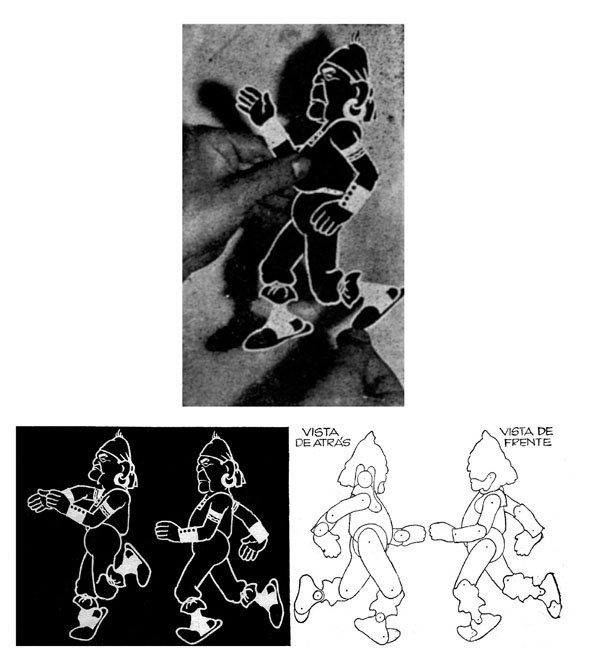

Yrigoyen figurines involved in “Peludópolis”’ animation.

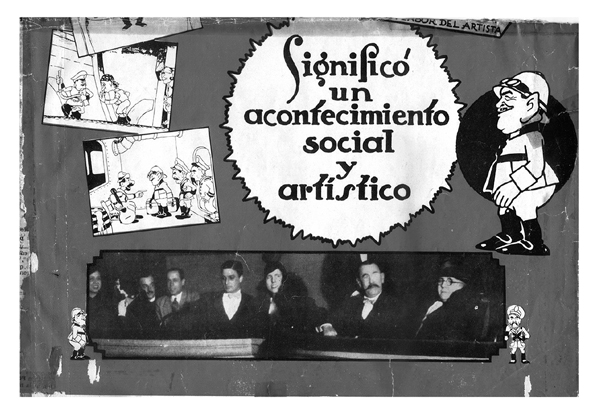

Peludópolis was shown as a “premiere” on September 16, 1931 at the Cine Renacimiento. It lasted one hour and twenty minutes, and the “General Provisional” himself, José Félix Uriburu, was in the audience. At the end of the film, he congratulated Cristiani and defined the film as a “great work of satire and a noteworthy acclamation of the Argentinean armed forces.”

Taken of an advertising flyer of “Peludópolis”. The mustached man in the photo is Uriburu.

Actually, Cristiani had mixed feelings. On one hand, the situation was too confusing. On the other, he did not know how to present himself to the public, who was just as confused as he was. In his opening credits, he inserted a short poem as a sort of disclaimer against passionate reactions that different factions might have had on seeing the film.

The abundant journalistic reviews seem to share Cristiani’s cautious perplexity, avoiding going too much into the political aspects of the film and praising -with certain reticence- its technical achievements, the success of the soundtrack (a system of synchronized discs), Vázquez Vigo’s musical score and the good-natured humor of the whole ensemble. The reticence is particularly relevant, because it shows a nuanced uneasiness to the realization that Cristiani’s style was beginning to look somewhat anachronistic. The grotesque, a key element in Argentine graphic art and humor until then, was starting to be perceived as out of place in the screen; perhaps as a product of the still very incipient “Disneysation” that was already operating in the field of animation.

Advertising clippings.

On the other hand, the social mood in Argentina was beginning to change. “El Peludo” was regaining popularity as the blunders and internal struggles of the military’s “provisional government” intensified. The death of the already elderly Yrigoyen, on July 3, 1933, together with the colossal homage that the man received (in which Cristiani also took part) ended up deciding the matter. “For reasons of ethics and in his memory”, in addition to the concrete market-related reasons, Cristiani recalled all copies of Peludópolis that were still in circulation and put them in storage. Financially, the project ended with a loss of about 25,000 pesos.

A recent find of documentarist Gabriele Zucchelli’s was a six-minute “making of” showing the creation of Peludópolis:

With the title Una visita a los Estudios Cristiani, this promotional documentary was shown before the feature started, since both animation and “talking movies” were quite rare. The brief film shows a very active studio with some assistants and several specialized technicians busy working on various steps of the animation process. The documentary contains an excerpted scene of El Peludo dancing a tango with a girl (who represents the Argentina), and also the technical production steps: paper puppets being cut-out, film being shot and developed, and finally the registration of music with José Vázquez Vigo directing the orchestra.

Animation techniques are illustrated by Quirino Cristiani himself, who was 34 at the time. It is worth noting that the cut-outs did not move similar to articulated figurines (as they did in “El apóstol”), but in phases—as in proper drawn animation.

Animated phases of Yrigoyen’s cut out figurine.

The technique was similar to the “slash” method used, for example, in the “Felix the Cat” cartoons, but with a variant: the absence of registration pegs. This is something that should never have worked -in theory-. A demonstration of the process, made by Cristiani himself forty years after the film and using the original materials, proves that it works… in Cristiani’s hands, of course.

“Peludópolis” animation.

In his old age, Cristiani talks about his animation technique (in Spanish):

Peludópolis did not mark an end point in Argentine animation or even in Cristiani’s career as animator, but with the film did finish something: the political satire as a theme. It is noteworthy that each piece mentioned in this series of articles was of a political or topical nature. Until then, the Argentine animated films had its roots clearly sunk in newspaper cartoons.

After the release of Peludópolis, the political joke, the cryptic chitty-chat of a small town where everyone knows each other too well, were banished forever from the screen. Cinema became not only a national, but a continental business. Argentina would be, in the following decades, the great exporter of Spanish-speaking cinema to all of Latin America (along with Mexico), and purely local themes were simply no longer part of the game. An era was over.

Epilogue

Valle, Ducaud and Cristiani conform a complex nebula, whose work is now mostly lost. Due to the effects of the compulsive “cristianization” caused by Bendazzi’s book (Quirino, practically unknown before, became almost the only actor in the story, unwittingly erasing the work of many others), Ducaud’s films were scarcely recorded in the subsequent history of cinema, and in fact, very little is known about him. This could be partly explained by his early death in 1943, but the explanation is not enough. Bendazzi mentions him with reluctance, an understandable phenomenon since the approach he had chosen to expose the subject was biographical, and that biography was clearly Cristiani’s. He seemed to forgot that cinema (and especially animated cinema) is a collective enterprise. The results of this amputation are still in effect. As example: some of the animations produced by Valle for its 1922 newsreel are shown in Youtube, but assigning all authorship to Cristiani, even when the work is signed by other cartoonists.

In any case, these small differences of valuation were saved by the general oblivion. Gone is the work of all of them, except for some miraculously preserved fragments, and what was not burned in the fire of the Valle Studios in 1926, ended up being sold as celluloid destined to the manufacture of combs after the definitive closing of the company (broken when the Argentine State took away its initial support to Valle’s investment destined to use the cinema as a didactic tool in public schools). The rest disappeared in the two other fires in Cristiani’s storage facilities twenty years later, in which his Peludópolis also went up in smoke. The hazardous improvisations that had allowed the creation of this material was the force that paradoxically also ended up reducing it to ashes. Every now and then, there is a dream of the appearance of copies treasured by a taciturn millionaire, a vinegar smelling widow, or magically emerging from the vault of some distant “Cinematheque”; and it is good that this happens. Those fantasies are also Cinema.

Fire on Valle’s Studio, 1926.

Valle died in 1960, and in his last years he was recognized in his role as a pioneer. Red carpets and strolls through film festivals could not erase the sense of defeat that came with the disappearance of most of his production. Something similar happened with Cristiani, who pass away in 1984, although Quirino was at least able to see his work recognized internationally. Ducaud is another case: no interviews or red carpets for him. Ducaud is the one that intrigues me the most.

But never despair. One thing we at least know about him is that he left descendants: Marina Valle, Federico’s daughter, recalled in an interview made by journalist Paraná Sendrós the day when, together with Ducaud’s children, they tied “the French ambassador’s son on the back of a pig (we told him he had to tame the pig) and on top of that we set the dogs on him. It was divine”.

Guys, if any of you were guilty of such an outrage and you are reading this, get in touch with the Museo del Cine (or me) as a matter of urgency. France -and the pig- have already forgiven you.

(1931 newspaper clipping – via Jorge Finkielman)

Bibliography:

Giannalberto Bendazzi, “Twice the First – Quirino Cristiani and the Animated Feature Film”, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2017.

Fernando Martín Peña, “Cien años de cine argentino”. Biblos, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012.

Domingo Di Núbila, “Cuando el cine era Aventura”, Ediciones del Jilguero, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1996.

Jorge Miguel Couselo, “Historia del espectáculo”. “Todo es Historia” magazine n°47, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1971.

Acknowledgements:

The author of this note would like to record the invaluable help received from the Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken”, especially through Pamela Gimena Vázquez and Fabián Sancho.

Drawing by Quirino Cristiani (circa 1930)

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

I’m intrigued by the drawing of the two masked and hooded Klansmen on the back of the “Peludopolis” poster. I wonder what sort of part they may have played in the film.

I knew that “peludo” means “hairy”, but I didn’t realise that President Yrigoyen’s nickname referred to a kind of armadillo! But yes, there are several species of hairy armadillo native to Argentina. Years ago I knew an Argentine violin dealer who had a charango (a small South American stringed instrument) made of a hairy armadillo shell hanging on the wall of his shop. It was pretty disgusting.

I’ve read that Quirino Cristiani met Walt Disney during the latter’s goodwill tour of South America in 1941. Cristiani’s studio was still in operation then, which would have helped to keep his name in the public eye despite the loss of his early films. Not so with Ducaud, who was still alive in 1941, so it seems that he may have faded into obscurity long before Bendazzi started telling Cristiani’s story. That patent lawsuit of 1923 must have caused a permanent rift between the two men.

It’s only a guess but I’d say those hooded men were a reference to one of those secret organizations that populated the period and the government (“wanna be a member?”). El Peludo is an armadillo, yes. The “charango” was originally built on his carcass, which was not so strange since the animal itself was considered food. Their hunting is prohibited today.

“Peludopolis” copies did exist in 1941, so there is a chance Walt saw the film or some excerpts (the fires in Cristiani storehouse are posterior). Ducaud seems to have left animation early on. The only document I could get on him suggest he was interested on sound film process by the late twenties. About the story of the combs (and regarding the doubts of Jorge Finkielman) the source was Valle itself (through Di Núbila), but of course it could be an embellishment.

Readers of this article may have noticed that there are two links disabled due to the disappearance of the Museo del Cine’s channel on YT. Here is a link to one of these films uploaded on another channel (the one that includes the animation of “Moglia”):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuqhDTEPi0Q&t=22s&ab_channel=LucasNine

Is there any chance of having the post edited to include the link?

Thank you Lucas Nine for writing this article about El Apostol , Peludopolis, Cristiani, Ducaud, et. al. I’ve heard of El Apostol for many years, but never saw as much from it as I have seen today. The animation is incredibly crude, and Cristiani and company had no idea of squash and stretch, overlapping action or even how to inbetween an action properly. Yet they made the first animated feature! I’ll bet this was an incredible chore to sit through. I liked the way Cristiani manipulated his cut-outs without any visible exposure sheet, just winging it under a stop-motion camera. Looks like 35mm, probably all that existed in those days. Incredible stuff, this is what Cartoon Research should have posted many years ago!

Thank you, Senor Nine! The past three Mondays, I have had my jaw drop open. To me, this was one of the most fascinating posts I’ve read on this Web site, and there have been thousands! I think it’s wonderful that we now have the details of those old, lost animated features.

Also, I think the models for the stop-motion animation films look great!

Thanks VERY much for posting these, and thank you, Mr. Beck, for making it possible.