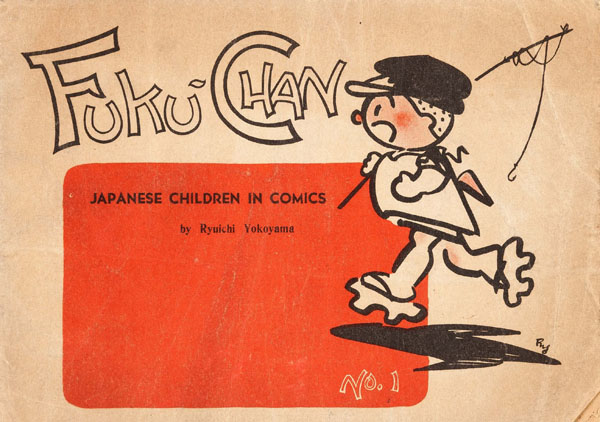

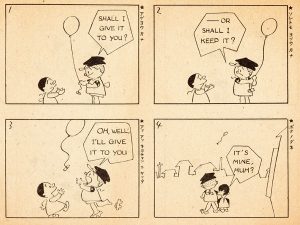

Otogi Production (translated as “Fairytale Production” in English) is one of those studios that deserves a closer look when it comes to discussing anime history. The animation studio was founded by Ryuichi Yokoyama (1909-2001), author and cartoonist best known for his long-running comic strip Fuku-chan, which ran in Asahi Shimbun newspaper from 1936 to 1971.

Ryuichi Yokoyama

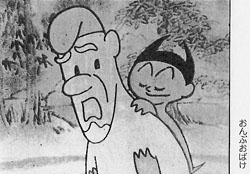

Following his meeting with Disney, Yokoyama would begin work on his own animated short, which resulted in Onbu Obake (“Piggyback Ghost”). Produced with a very small crew, Yokoyama had several roles in the production: directing, writing, drawing, and photography, with Mitsuhiro Machiyama helping out on the animation front. The silent, 23-minute film, which was made on a 16mm color stock, had a limited screening in December 1955.

Upon the release of Onbu Obake, Yokoyama formally started Otogi Production in 1956. Despite Yokoyama’s ambitions to be the Japanese Disney, there were questions whether that could be achieved. Shin’ichi Suzuki, who got his start in the animation field working at Otogi, recalled “he had a dream to make Otogi Production as big as Disney, but he was a daydreaming comic artist and not much of a businessman. One felt that it started off as a hobby for him, and finished as one, too.” Suzuki recalled how he got hired at Otogi when, during his meeting with Yokoyama, he asked the young artist to draw a hippopatamus doing a headstand. Suzuki obliged, and he got the job.

Upon the release of Onbu Obake, Yokoyama formally started Otogi Production in 1956. Despite Yokoyama’s ambitions to be the Japanese Disney, there were questions whether that could be achieved. Shin’ichi Suzuki, who got his start in the animation field working at Otogi, recalled “he had a dream to make Otogi Production as big as Disney, but he was a daydreaming comic artist and not much of a businessman. One felt that it started off as a hobby for him, and finished as one, too.” Suzuki recalled how he got hired at Otogi when, during his meeting with Yokoyama, he asked the young artist to draw a hippopatamus doing a headstand. Suzuki obliged, and he got the job.

There’s the matter of the size of the studio, too. His staff nicknamed it “Tatami Production” because much of the work was done on the tatami floors in Yokoyama’s house. Nonetheless, Yokoyama benefited from having name recognition as a successful (and not to mention well-paid) cartoonist, and the fact that there was very little competition in Japanese animation at the time due to the industry being very minuscule

Much of the staff working at Otogi had very minimal animation experience, including Yokoyama himself. While his Fuku-chan strip was adapted into animation previously (Yokoyama even gets a co-directing credit for Fuku-chan’s Submarine) his involvement in the actual production was, at best, minimal. When it came time to produce his first 35mm production Fukusuke (no relation to his comic strip), Suzuki recalled that Yokoyama would “direct” by simply pointing a page from his children’s book and telling the animators to have it done by the end of the day. “Every day Mr. Yokoyama would say ‘today we’re doing this’. And gave me a drawing of, for example, a frog on a tracing paper which he would ask me to ‘move like this’.” While Suzuki found the process to be haphazard, he recalled the experience to be entertaining. Suzuki added that the shot lengths were an approximation, but even if the produced footage exceeded the planned length, “that was fine.” It wasn’t until the arrival of artist Hajime Maeda, whom Yokoyama worked with previously during the war, were exposure sheets properly introduced at Otogi.

Much of the staff working at Otogi had very minimal animation experience, including Yokoyama himself. While his Fuku-chan strip was adapted into animation previously (Yokoyama even gets a co-directing credit for Fuku-chan’s Submarine) his involvement in the actual production was, at best, minimal. When it came time to produce his first 35mm production Fukusuke (no relation to his comic strip), Suzuki recalled that Yokoyama would “direct” by simply pointing a page from his children’s book and telling the animators to have it done by the end of the day. “Every day Mr. Yokoyama would say ‘today we’re doing this’. And gave me a drawing of, for example, a frog on a tracing paper which he would ask me to ‘move like this’.” While Suzuki found the process to be haphazard, he recalled the experience to be entertaining. Suzuki added that the shot lengths were an approximation, but even if the produced footage exceeded the planned length, “that was fine.” It wasn’t until the arrival of artist Hajime Maeda, whom Yokoyama worked with previously during the war, were exposure sheets properly introduced at Otogi.

The 18-minute Fukusuke (also known as “Top-Heavy Frog”) was given a theatrical release by Toho in 1957. Despite the haphazard production and technical issues (among other things, the color on the film stock often fluctuated in different shots because unexposed cuts of film were used to save cost, but the staff had no understanding of emulsion numbers on the canisters), the film did well, even winning an award at the Mainichi Film Festival in 1958.

The 18-minute Fukusuke (also known as “Top-Heavy Frog”) was given a theatrical release by Toho in 1957. Despite the haphazard production and technical issues (among other things, the color on the film stock often fluctuated in different shots because unexposed cuts of film were used to save cost, but the staff had no understanding of emulsion numbers on the canisters), the film did well, even winning an award at the Mainichi Film Festival in 1958.

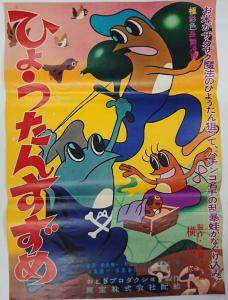

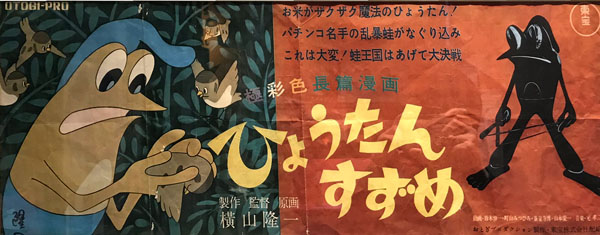

Otogi followed up with a second film for distribution with Toho, a 55-minute Hyotan Suzume, or “Sparrow in the Gourd”. The film centers on Danbe, a violent gang leader frog who’s an expert marksman with his slingshot, and his son sailing to a small village on an island inhabited by other frog people. Danbe immediately causes problems upon arriving at the island, including getting tangled with the kind-hearted Zensuke and his daughter, who take care of the sparrow population on the island.

As with other Otogi cartoons, the film was produced with a skeleton staff of less than two dozen (including animators, cel painters, composer, voice actor, etc.). The film’s animation and technical aspects were vastly improved (though not without flaws) from the earlier Fukusuke. While the film is majority hand-drawn cel animation, other techniques were achieved to save cost, from cut-outs to stop-motion, like the postcard Danbe produced when he arrived at the island, to the white flags when the frogs surrender after Danbe takes over the island.

The highlight, for me, is the climax when Danbe battles with the gourd monster, which has really fun and bouncy animation that’s reminiscent of the Fleischer Studios cartoons. That sequence was largely animated by Shin’ichi Suzuki, showcasing how confident he got with his animation after his rough start with Otogi.

The highlight, for me, is the climax when Danbe battles with the gourd monster, which has really fun and bouncy animation that’s reminiscent of the Fleischer Studios cartoons. That sequence was largely animated by Shin’ichi Suzuki, showcasing how confident he got with his animation after his rough start with Otogi.

While Ryuichi Yokoyama is still a relatively well-known creator in Japan, his animation output is largely forgotten. Despite the hectic way he ran his studio, the films it produced are worth checking out, and are entertaining to watch. Otogi Production made bigger splash when they started producing a series of three minute cartoons for Tokyo Broadcasting System called Instant History in 1961, considered the first TV anime series to be shown. The company existed, at least on paper, until 1971, when it was dissolved for good.

You can watch Hyotan Suzume below. While there are unsubtitled Japanese narration, the film is largely told visually and can be understood easily.

Production data and staff

Released February 10, 1959 by Toho

Directed by: Ryuichi Yokoyama

Animation: Shin’ichi Suzuki, Mitsuhiro Machiyama, Hiroshi Hatazumiji, Eiichi Yamamoto, Yukihiro Yamada, Toshiro Nagata, Masashi Ito

Background: Takeki Nakahara

Ink and Paint: Katsuko Nagai, Emiko Taguchi, Kyoko Kimura, Ayako Uchiyama, Nagako Tomono, Taeko Ichihara, Teruko Koyama, Sumiko Sekine

Photographed and Edited by: Yoshitaka Komatsu, Emiko Okada, Hiroshi Okubo

Music: Koji Taku

Sound Recording: Masao Kunishima

Narrator: Kiyoshi Kawakubo

Charles Brubaker is a cartoonist originally from Japan. In addition to his work for MAD Magazine and SpongeBob Comics, he also created Ask a Cat for GoComics. You can also follow him on his Tumblr page.

Charles Brubaker is a cartoonist originally from Japan. In addition to his work for MAD Magazine and SpongeBob Comics, he also created Ask a Cat for GoComics. You can also follow him on his Tumblr page.

“A frog in the well knows nothing of the sea, but it knows the blueness of the sky.” — Japanese proverb

I enjoyed this film more than you can imagine. For a number of years I used to keep native frogs of several species, most of which I raised from tadpoles. At one point I had well over a hundred of them. It was during this period that I made my first tour of Japan. People there thought that keeping frogs was a very interesting hobby; I recall one interviewer who asked me question after question about frogs, and little else. I wound up getting a very large number of frog-related gifts: figurines, toys, fans, kakemono, origami, you name it. I’m going to have to ask my Japanese friends if they’re familiar with Hyoutan Suzume. It’s now one of my all-time favourite frog anime — I’m a big fan of Keroro Gunsou!

I quite like Koji Taku’s musical score, sort of equal parts Igor Stravinsky and Leonard Bernstein. The opening title music sounds like something out of a UPA production. I also noticed that, as in American animation studios at the time, the Ink and Paint department was staffed entirely by women.

Doumo arigatou gozaimashita, Brubaker-sensei.

That was an enjoyable watch, thanks for the post. The great music helped sustain interest too until the finale, which was also my favorite part.