Up until now, this review of the musical elements from the Max Fleischer “Song Car-Tunes” has dealt with titles for which there presently is no readily-known visual reference. Data exists out of filmographies, but it is unknown whether these compilations derive solely from copyright registries, or whether archival prints are hidden away in some remote vault in Siberia or the like. However, commencing in 1926, a monthly schedule of Song Car-Tunes began to be released with sound, the Fleischers re-teaming with the DeForest Phonofilms system in another attempt to launch sound on film cartoons. Although this experiment lasted a good deal longer than the previous 1924 efforts, one can only presume from the general lack of fame and prestige they brought the Fleischer studio that the effort was again largely overlooked, or simply commercially inaccessible for the average theatre-goer. DeForest also achieved no lasting fame from their inclusion within his programmes, and his ultimate bouts with the Vitaphone in the court system would eventually bring an end to even his live-action experiments – although his pioneering work seems to have been eventually subsumed into what became the Fox Movietone process, with more sophisticated amplification and standardization of film speed to match conventional Vitaphone.

Up until now, this review of the musical elements from the Max Fleischer “Song Car-Tunes” has dealt with titles for which there presently is no readily-known visual reference. Data exists out of filmographies, but it is unknown whether these compilations derive solely from copyright registries, or whether archival prints are hidden away in some remote vault in Siberia or the like. However, commencing in 1926, a monthly schedule of Song Car-Tunes began to be released with sound, the Fleischers re-teaming with the DeForest Phonofilms system in another attempt to launch sound on film cartoons. Although this experiment lasted a good deal longer than the previous 1924 efforts, one can only presume from the general lack of fame and prestige they brought the Fleischer studio that the effort was again largely overlooked, or simply commercially inaccessible for the average theatre-goer. DeForest also achieved no lasting fame from their inclusion within his programmes, and his ultimate bouts with the Vitaphone in the court system would eventually bring an end to even his live-action experiments – although his pioneering work seems to have been eventually subsumed into what became the Fox Movietone process, with more sophisticated amplification and standardization of film speed to match conventional Vitaphone.

From this 1926 period of experimentation, we are finally able to witness what the Song Car-Tune had become, as there are several surviving films. Frequently, the animation content would in fact be at a minimum. The concept of plot had not yet occurred to Fleischer for inclusion in these vehicles, and the animation was generally a few random gags or the setup of an orchestra or glee club for framing, followed by the trademark bouncing ball with lyric, and climaxed with a verse animated in transforming visual puns. The animated verse ending would continue into the early 1930’s. when it would for the duration of the black and white output be abandoned for a considerable time in favor of live-action segments using guest celebrities. By 1929, more attention would be placed upon the prologue, which, even if not always developed into a plot, would at least attempt to provide us with one-third to one half cartoon content. The sophistication of the animation would run a close parallel to the contemporary Talkartoons or other series in concurrent production with the “Screen Songs”, until the Song’s wraparaounds were virtually indistinguishable in quality from the animation of the more prestigious star series of Popeye, Betty Boop, etc. – even allowing for character crossovers, as Ko-Ko frequently did in the early efforts. Bit I’m getting ahead of my story. And so, we return to what is known of the late 1925 output, and into the beginnings of the survivors of 1926.

From this 1926 period of experimentation, we are finally able to witness what the Song Car-Tune had become, as there are several surviving films. Frequently, the animation content would in fact be at a minimum. The concept of plot had not yet occurred to Fleischer for inclusion in these vehicles, and the animation was generally a few random gags or the setup of an orchestra or glee club for framing, followed by the trademark bouncing ball with lyric, and climaxed with a verse animated in transforming visual puns. The animated verse ending would continue into the early 1930’s. when it would for the duration of the black and white output be abandoned for a considerable time in favor of live-action segments using guest celebrities. By 1929, more attention would be placed upon the prologue, which, even if not always developed into a plot, would at least attempt to provide us with one-third to one half cartoon content. The sophistication of the animation would run a close parallel to the contemporary Talkartoons or other series in concurrent production with the “Screen Songs”, until the Song’s wraparaounds were virtually indistinguishable in quality from the animation of the more prestigious star series of Popeye, Betty Boop, etc. – even allowing for character crossovers, as Ko-Ko frequently did in the early efforts. Bit I’m getting ahead of my story. And so, we return to what is known of the late 1925 output, and into the beginnings of the survivors of 1926.

Swanee River (1925, silent), uses the original spelling of the Stephen Foster classic. For reasons unknown, the recording industry in the early days generally seemed to favor the sonf’s scondary title, “Old Folks at Home”, and often gave the number to artists of classical or at least concert fame. The illustrious Nellie Melba recorded it on Victor’s special “Melba” record series in the early acoustic days. Alma Gluck and Efrem Zimbalist, and Ernestine Schumann-Heink, each recorded their own versions for Victor’s red seal series. Fritz Kreisler would record it as a violin selection for Victrola red seal. Elsie Baker would cover it for black label Victor, When electrical recording came along, Paul Robeson recorded it for HMV. Riley Puckett performed a country vocal with guitar on Columbia. Deanna Durbin would record it for Decca. Bing Crosby provided a sentimental vocal version on Decca. For a more swinging vocal style, there was the Mills Brothers on Decca. Tommy Dorsey swung a few curves into it on Victor. Harry James did likewise on Varsity, Bunny Berigan on Victor, Gene Krupa, on Brunswick, and Jimmie Lunceford on Decca Sammy Kaye included it in a Stephen Foster album set on Victor. Across the pond, Django Reinhardt and the Hot Club of France would play it hot on Ultraphone.

And a forgotten piece of Walter Lantz studio history would have the music track (without dialogue) of a very slow version of the tune released as side two of a Universal Studios promotional disc prepared to correspond with the release of what amounted to the studio’s first “Swing Symphony”, Scrub Me Mama With a Boogie Beat. Such recording provided the underscore for the first third of the cartoon – life in “Lazy Town” before the Lena Horne look-alike arrives to liven things up.

My Bonnie (1925, silent) – The song probably dates from 19th Century England. No really early recordings have been sighted, but it appears as part of country repetoire by the Leake County Revelers (violin, banjo, mandolin and guitar) on early electrical Columbia. Ella Logan recorded one of the best known, lighrtly swinging versions on Brunswick. Glen Gray gave it a band approach for Decca, and later the same label would try their own vocal version with Ella Fitzgerald. Jimmy Shand would record it for Parlophone. And the version that draws the biggest price tag was for Decca (later picked up by MGM) was by the Beatles with Tony Sheridan (originally billed as “Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers”), at a time when the group would have been unknown outside of their own country.

Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-Dee-Aye (1925, silent). The song, published around 1891, was not a hit. The song curiously was offered to bicycling clubs in England, who turned it down. Eventually, it somehow wended its way into the British Music Hall circuits, and became established. It received very few recordings for the adult audience – in fact, the earliest recording on the inrternet is a home recording by a little girl of undetermined age on wax cylinder. Notable recordings from much later included Gene Krupa on Brinswick (using the number’s original spelling, “Ta Ra Ra Boom Der E”), and inclusion in the “Old Timers’ Night at the Pops” medley for Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops on RCA Victor, and in England in a Fair Organ Medlet entited “Fun at the Fair”. Little Golden Records inevitably gave it to Gilbert Mack and Anne Lloyd with Mitch Miller’s orchestra, with rewritten lyrics – a version that stayed in catalog a considerable length of time.

Sailing, Sailing (1925, silent) – a maritime chestnut, which found its way into later use with Popeye and in just about every other nautical situation ever presented in animation. An early electrical from 1926 by the Victor Concert Orchestra (possibly headed by Rosario Bourdin, who would later provide the score for Charles Mintz’s first talking Krazy Kat, Ratskin), pairs the song in a medley with ‘Sweet and Low”. Due to the number’s short time span, few other commercial recorrdings of vintage exist. A snip of the tune would appear in Billy Costello’s Brunswick recording of “I’m Popeye the Sailor Man”. Little Golden Records in the 1950’s would combine the tune with Popeye’s other favorite nautical theme, “Sailor’s Hornpipe”, under the direction of Mitch Miller. And the piece would become a basis for two different film theme versions (by Sam Singer and Hanna-Barbera) for American International’s syndicated series, Sinbad Jr. and his Magic Belt.

My Old Kentucky Home (Jan, 1926, sound) marks a milestone for this survey. The first of the Song Car-Tunes to be known to be represented by a surviving film, and also a return to the DeForest Phonofilm system. It further is reputed to be a milestone for actually attempting to have a character talk on screen with semi-sychronized dialog, in the form of one line. Not much plot. A dog comes home to his apartment, and pulls out from a “hidey-hole” a large ham. The soundtrack accompanies this with the standard Jewish “marker” cue, “Mazel Tov”. He then cuts off all the meat from the ham, deciding to enjoy the bone, whether it’s Kosher or not. He takes his dentures out of his mouth, ad one tooth falls out, so he uses a hammer to put it back in, allowing for another musical cue as his hammering is timed to the Anvil Chorus. After eating, one end of the bone, he turns the rest of it into a trom-bone, playing a bit of the title tune, with “wah-wah” effects thrown in (which are somehow accomplished without the aid of a visible plunger). The character then delivers the one spoken line in the picture: “Follow the ball and join me, everybody”. I do not recognize any of the members of the quartet which then performs the tune vocally. We get a first chance to see the Fleischer animators having visual fun with the final chorus, including one line of lyric tipping in see-saw effect.

My Old Kentucky Home (Jan, 1926, sound) marks a milestone for this survey. The first of the Song Car-Tunes to be known to be represented by a surviving film, and also a return to the DeForest Phonofilm system. It further is reputed to be a milestone for actually attempting to have a character talk on screen with semi-sychronized dialog, in the form of one line. Not much plot. A dog comes home to his apartment, and pulls out from a “hidey-hole” a large ham. The soundtrack accompanies this with the standard Jewish “marker” cue, “Mazel Tov”. He then cuts off all the meat from the ham, deciding to enjoy the bone, whether it’s Kosher or not. He takes his dentures out of his mouth, ad one tooth falls out, so he uses a hammer to put it back in, allowing for another musical cue as his hammering is timed to the Anvil Chorus. After eating, one end of the bone, he turns the rest of it into a trom-bone, playing a bit of the title tune, with “wah-wah” effects thrown in (which are somehow accomplished without the aid of a visible plunger). The character then delivers the one spoken line in the picture: “Follow the ball and join me, everybody”. I do not recognize any of the members of the quartet which then performs the tune vocally. We get a first chance to see the Fleischer animators having visual fun with the final chorus, including one line of lyric tipping in see-saw effect.

Harry MacDonough recorded the tune for Victor in 1901, followed by the Haydn Quartet circa 1902. Columbia also recorded it in 1901 or 1902, with no artist credit, billed simply as “minstrels”. Alma Gluck recorded it for Victor Red Seal, probably from about 1909. Helen Louise and Frank Fererea gave it a Hawaiian guitar treatment for early Columbia, then re-recorded it for Pathe Actuelle. Louise Terrell and the Shannon Four recorded a 20’s version acoustically for Silvertone. A very early electrical appears by opera star Rosa Ponselle on red seal Victor. Bob MacGimsey, a singer and whistler, performed a country version for electrical Victor. A quartet known as the American Singers recorded it for electrical Columbia. Paul Robeson provided an electrical performance for HMV. Richard Crooks recorded a Victor Red Seal in the 1930’s. Bing Crosby crooned it for Decca. Gene Krupa gave it the swing treatment on Columbia. Sammy Kaye gave it Swing and Sway on Victor. Marian Anderson recorded a Victor Red Seal version in the 1940’s. Nelson Eddy recorded it for Columbia Masterworks in the 1940’s.

Darling Nellie Gray (February, 1926, sound) Not much plot to speak of. The song might bring some embarrassment to a singing audience today, as it dates from the pre-Civil War era. A group called the “American Quartet”, though not yet the group that would achieve fame with Billy Muttay, was recorded in performance of it for Victor Monarch in 1901. C. Carroll Clark recorded an early version on Columbia about 1907, reissued on Standard and Lakeside. Another Columbia was released in the classical series by Alice Nielsen in the early teens. Samuel Gardner performed a violin solo on Victor circa 1915. Alma Gluck recorded a 1917 version for red seal Victrola. Marie Tiffany, a concert soprano, recorded an acoustical version on brass-label concert series Brunswick in the early 20’s. The Peerless Quartet recorded it accoustically and Shannon Quartet electrically for Victor in the 1920’s. Al Bernard performed it in Radiex avout 1927. Asa Martin and James Roberts, singers from Kentucky, recorded it for Conquerer circa 1932. Louis Armstrong and the Mills Brothers jazzed it up for Decca (below). Maxine Sullivan recorded it for Vocalion about 1937. Bing Crosby also covered it for Decca in the late 1930’s. Carson Robison and his Old Timers adapted it for square dancing on Columbia in the 1940’s. Claude Shape with Kitty Wells performed a 1949 country version on Columbia.

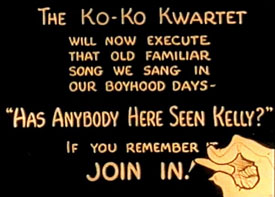

Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly? (March 1926, sound) – no plot whatsoever – just an animated band coming on stage, introducing the Ko-Ko Glee Club singing the title tune. More of the second chorus monkeyshines.

Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly? (March 1926, sound) – no plot whatsoever – just an animated band coming on stage, introducing the Ko-Ko Glee Club singing the title tune. More of the second chorus monkeyshines.

The song goes back to England In 1905, referring to “Kelly from the Isle of Man”, but this version opts for the 1909 Americanization of the tune, describing Kelly as an Irishman. Nora Bayes’ version on purple seal Victor, and Ada Jones on black label Victor and Indestructible cyllinder, were probably the best sellers. Other versions included English versions on Edison Cylinder, and by Florrie Forde for Edison Bell Radio 8 inch in about 1929.

When The Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam (April, 1926, sound) – What little plot there is shows a crowd of people going through an archway to the trains, one character not making it before the gates close. The song, a 1913 composition by Irving Berlin, was recorded by Collins and Harlan for Victor and Columbia. It was also popular in England, where G. H. Elliot, who styled himself a “chocolate covered” entertainer, recorded it for Zonophone in 1913. Tommy Dorsey’s Clambake 7 recorded a swinging version for Victor. The Andrews Sisters recorded it in the 1940’s for Decca. A soundtrack performance by Judy Garland and Fred Astaire, from “Easter Parade”, was issued on MGM records.

More echoes from the poorly-attended halls of the DeForest screenings, next time.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

“Old Folks at Home” is the original title of Stephen Foster’s song. Irving Berlin, who had a framed portrait of Foster on the wall of his office, quoted part of its melody in “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”, set to the lyrics “And if you care to hear that ‘Swanee River’ played in ragtime….” It was so popular that “Swanee River” became cemented in the collective consciousness as the title of the song. About ten years later George Gershwin and Irving Caesar took a page from Foster (and another from Berlin) with their song “Swanee”, which, after Al Jolson recorded it and added it to his revue, became Gershwin’s first big hit and, in terms of sheet music sales, the biggest of his career.

The jazz rock band Chase recorded a rocking version of “Swanee River” as the opening track on their second album, “Ennea” (1972).

I don’t know by what criteria you claim that “Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-Dee-Ay” was “not a hit”, but it was certainly popular enough that an alternate stanza set to the song’s verse became widely circulated during the Lizzie Borden trial in 1892:

Lizzie Borden took an axe,

Gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done,

Gave her father forty-one.

Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-day, etc.

The song, of course, is best known to Baby Boomers as “It’s Howdy Doody Time!”

“When That Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for Alabam'” is played at the beginning of the Fleischer Talkartoon “The Betty Boop Limited”.