Illustration from “Theater Organ Bombarde” October 1969

1926 was a good year for research and development into sound pictures. Warner Brothers put on their first program of such films, with their sound-on-disc Vitaphone system. Features such as Don Juan and The Better ‘Ole, as well as the short films that accompanied them, impressed many in the industry. Around the same time, William Fox was working with Messrs. Case and Sponable on a sound-on-film system, which eventually became Fox Movietone. Things would come to a head in 1927, with the release of The Jazz Singer. Amidst all this, Fleischer was still working to develop sound cartoons, which didn’t need to depend on dialogue, but to rely upon music and sound effects. However, partway through this year, and into the 1926-27 season, Fleischer abandoned the use of soundtracks with the DeForest Phonofilms system. Perhaps he was seeing the writing on the wall that other companies were developing the talking picture in ways that would eventually eclipse the DeForest process, and may have decided to bide his time and see which of the rival systems would become the victor and the standard. Having no distribution ties to any of the majors involved in the experimentation, he was also likely waiting for the right break to obtain access to more readily available avenues for having his sound efforts publically seen, and so would put his experiments on the back burner until the time for new success was ripe.

Tramp Tramp Tramp (May, 1926, sound) – Again, no real plot material – just the Ko-Ko Glee Club and a band setting itself up on stage (some of the same footage seems to reappear in the later “Sweet Adeline”). The song goes back to the civil war era. Byron G Harlan and Frank Stanley recorded it for Victor around 1906. Clarence Whitehill, a concert singer, covered it on Victor red seal about 1915. Charles Harrison and the Columbia Stellar Quartette recorded it for Columbia about 1917 (when it was getting some reassociation with the troops now marching in World War I).

Sweet Adeline (June 1926, sound) – no plot material again. The anthem for male quartets in various stages of inebriation. In fact, an organization for female barber shop quartets is currently known as the “Sweet Adelines”. The Hadyn Quartet recorded it for Victor. The “new” Peerless Quarter (Cark Mathieu, James Stanley, Stanley Baughman, and Henry Burr) recorded it electrically for Victor in 1926 – Burr had replaced everybody but himself in 1925. The Mills Brothers had a notable version during the barber shop quartet revivals for Decca. Tommy Dorsey had a version for Decca in the 1950’s. One of the most remembered versions was its inclusion for years in the soundtrack of Disneyland’s “America Sings”, performed by an intoxicated crane known as “Blossom Nose Murphy” with the usual barber shop backup.

Old Black Joe (July, 1926, sound) – Another Stephen Foster melody. This film hasn’t yet shown up for visual inspection, and its title suggests it as unlikely to appear due to political incorrectness, if not nitrate deterioration.

The Haydn Quartet recorded a 1902 version for Victor’s “Monarch” label. The Peerless Quartet recorded an early version for Victor, when their label was bragging of winning a “grand prize” at a World’s Fair. They later anonymously recorded it as the “Columbia Quartette” on Columbia, and under their own name on English vertical-cut Rex, and for Gennett. Henry Burr would also do it without the quartet on 7″ Emerson. The Taylor Trio (violin, cello, and piano) gave us an instrumentally on Columbia. Alma Gluck again was selected for a recording on Victrola red seal. Elizabeth Spencer waxed it for Paramount. Christine Miller, a concert soprano, performed it for Edison Diamond Disc and on blue label Victor. Another soprano, Marie Tiffany, covered it for Brunswick. Sam Moore (who played an eight-string guitar fretted with a steel bar called an octochorda, played in Hawaiian fashion) and Horace Davis dueted the number for Columbia around 1922. Riley Puckett gave it the country sound on acoustic Columbia. A Grey Gull version was billed as “Bob Thomas” – most likely, Ernest Hare. May Peterson was issued on Vocalion red record. Lawrence Tibbett recorded it electrically for Victor Red Seal in the late 1920’s. Nat Shilkret included it in an album of Foster melodies on what was considered the “junior red seal” series, at the lowest price the label offered, for Victrola. Richard Crooks also performed it electrically for Victor red seal. Sam-Ku-West, another Hawaiian guitarist, performed it on scroll Victor. Paul Robeson issued it for HMV. Later, the Mills Brothers would syncopate the piece for Decca. A Decca Salon Orchestra fronted by Harry Horlick would issue it as part of another Foster set on concert series red label Decca. The Four Squires, a more modern sounding vocal group, recorded a 30’s version for Vocalion. Glenn Miller gave it a polished version on Bluebird. Tommy Dorsey also contributed a version for Victor. Gene Krupa again give it the swing treatment for Columbia. Frank Luthur and the Lynn Murray Quartet sang it for Decca. Sammy Kaye again included the number in a Stephen Foster album set for Victor in the 1940’s. Here’s a version by Roy Rogers and The Sons Of The Pioneers:

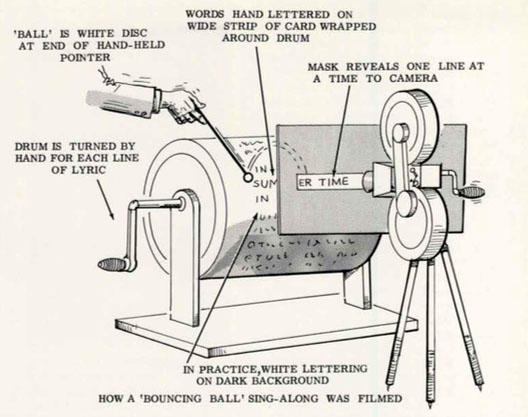

By the Light of the Silvery Moon (August, 1926, sound) – The bouncing ball actually becomes the moon in this one. Victor gave this number to Billy Murray and the Haydn Quartet. Columbia had Ada Jones. The song was revived various times, including an up to date swing treatment by Ray Nobe for Columbia in 1941, with Snooky Lanson on vocal. Fats Waller and the Deep River Quartet included the numbeer in their last commercial session for Bluebird in 1942. Phil Regan performed it on Majestic in the mid-1940’’s. Bing Crosby crooned in his usual style on Decca. Guy Lombardo also provided band coverage on Decca. Al Jolson got to wax it in his comeback period for Decca. Doris Day would use the number as tite for another of her Warner pictures, also recording it on Columbia. Jane Powell would also feature the number nostalgically in the picture Two Weeks With Love for MGM (embed below), with soundtrack disc issued on the same label. Les Paul electrified it for Capitol. Johnny Maddox on Dot would give it a ragtime feel on piano in the 1950’s, and Jackie Lee also gave it the piano treatment on Coral. Etta James would record a 50’s version for Modern. Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps sold a rockabilly version for Capitol. Jimmy Bowen updated it for Roulette in 1958. Even Little Richard on Specialty, and Jackie Wilson on Brunswick, gave it late rocking revivals.

Yacka Hoola Hickey Dula (1926) – A tin pan alley song from 1915 – a year when the songwriters went wicky-wacky over anything with island imagery. Victor gave it to the Avon Comedy Four, a group which included Irving Kaufman, the hyper-prolific singer of vocal refrains on many a 1920’s dance record, plus Joe Smith and Charles Dale (the inspirations for Neil Simon’s film hit, The Sunshine Boys). Columbia gave the song to Al Jolson, then a 31 year old singer on his way to tremendous fame and fortune. Colluns and Harlan covered it for Pathe and concurrently rewaxed it for Victor. Red Nichols jazzed it up for Brunswick in the early 1930’s (embed below). The song was revived much later by Len Fillis under the name Lynn Milford and His Hawaiian Players on English Regal, Ray Kinney on Decca, Spike Jones and his City Slickers on RCA Victor, and George Lewis and his New Orleans Musuc on Good Time Jazz.

Comin’ Through the Rye (presumed 1926) – One of the traditional Scottish melodies, with a lyric originally written by Robert Burns. Many animation fans will remember it used as the leirmotif for the appearance of Bad Luck Blackie at MGM. A band version was recorded by Arthur Pryor for Victor at least as early as 1907. Victor Red Seal gave the song to several of its sopranos – Nellie Melba, Alma Gluck, and later Marion Talley in an electrical version. One Florence Hinkle also recorded it for Victor blue label. Columbia covered with a classic pair-up of sisters Rosa and Carmela Ponselle (Carmella made a fair number of recordings during this period, and the two had made the unusual quantum leap from vaudeville to the Metropolitan). Nevada Van Der Veer recorded it in the 1920’s for Arto and Bell (produced for W. T. Grant stores). The song was revived in the swing era by Tommy Dorsey on Victor, and in a much straighter version by Lawrence Welk on Vocalion:

For Me and My Gal (1926) – a 1917 song, recorded by Van and Schenck (styled, “the pennant-winning battery of Songland”) for Victor. Sam Ash recorded it for Edison. In the late 1930’s, Guy Lombardo revived it for Decca. Judy Garland and Gene Kelly would make it the title song for a 1942 Busby Berkeley feature, and concurrently record a studio version for Decca. Abe Lyman also performed a 40’s version for Bluebird. In 1947 it was further revived by Arthur Godrey (as the B-sode of his best-seller, “Too Fat Polka”) for Columbia.

I’d Love To Fall Asleep (1926) – Unless and until thus cartoon shows up, it will remain a mystery precisely which song this cartooon featured. A possible candidate is I’d Love to Fall Asleep and Wake Up In My Mammy’s Arms, performed by the Peerless Quartet on Victor. Flo Bert (who would become the wife of Scandahoovian -accented comedian El Brendel of Fox pictures and Columia shorts fame) performed it for Paramount. Billy Jones and the Harmonizers Quartet appeared with it on Grey Gull, and in England Fred Douglas issued it on Regal.

Time we all fell asleep – to dream of still more silent output next time.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

All those Hawaiian-themed songs that came out in 1915 were inspired by the Hawaiian Pavilion at the Panama-Pacific Exposition, a world’s fair held in San Francisco that year to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal as well as the city’s recovery from the ’06 earthquake. The Hawaiian dancers and musicians were hugely popular, drawing bigger audiences than even John Philip Sousa’s band, and ukuleles became all the rage. Tin Pan Alley, always looking for a trendy fad to hammer completely into the ground, seized the opportunity to do so.

I’m reminded of an episode of Family Guy where Quagmire takes Chris to a party on the beach, which devolves into a musical extravaganza called “Hic-a-Doo-La”, a dead-on parody of those American International beach party movies of the sixties. But I much prefer the Red Nichols version — that’s some red-hot jazz fiddling there!

About 18 of the Ko-ko Song Car-tunes were produced with deForest Phonfilm soundtracks between 1925 and 1927. The “abandonment” was not as speculated here, but due to the bankruptcy of The Red Seal Pictures Corporation with was a partnership between the Fleischers, Hugo Riesenfeld, and Dr. Lee deForest. The company owned 36 theaters that had the Phonofilm equipment installed. The sound equipment was also installed temporarily on other theaters for short term demonstrations. Red Seal was acting as its own distributor, so distribution was not the issue. It was timing and the fact that Red Seal was a small company that came a little too early to become serious competition for the majors or to merit their attention. The company went out of business five months before the release of THE JAZZ SINGER.

The Case-Sponable was an extension of the deForest optical soundtrack process, which was based on the Variable Density method, which had seems to have originated in Germany. Theodore Case had developed a photo electric cell that deForest needed in his development and the two worked on further development for two years. Some of the early Phonofilms credit deForest and Case on the Main Titles. After a dispute over the Calvin Coolidge Speech on the Economy, Case left deforest and joined forces with Sponable. They in turn went to William Fox, who entered into a joint venture with Western Electric to form the Fox Movietone Newsreel in 1927 just prior to the release of THE JAZZ SINGER.

The lack of sound equipment in the majority of the theaters explains the 18 month gap in the release of sound films and why it was not until 1929 that it appears that Fleischer had not returned to producing sound cartoons. After Max and Dave left Inkwell Studios following a dispute with Alfred Weiss, they formed Fleischer Studios in February, 1929. Max managed to secure a contract with Paramount, and they returned to the Bouncing Ball song format they had established, this time with more elaborate animation. The timeline indicates that they had left Weiss some time in late 1928 since records show that the first SCREEN SONG was running on Broadway in the fall of 1928. When Walt Disney arrived in New York to record the soundtrack to STEAMBOAT WILLIE he mentioned seeing SIDEWALKS OF NEW YORK. While the Copyright is in February 1929, this indicates that many films were previewed in New York before going into general release. By this time Paramount had licensed sound recording with Western Electric and was in the process of installing sound equipment in its theaters. This would explain the five to six months gap between the New York screening and the Copyright date, which generally refers to the general release date.

As for the post of TRAMP TRAMP TRAMP, it was originally released in 1924 as one of the silent releases. This clip has a recorded added that had nothing to do with the sound version. The sound re-release came during the 1928-29 Weiss period when the Fleischers had left. Weiss re-released a number of the Fleischer’s films as sound releases including some of the OUT OF THE INKWELL films using what sounds like the Powers Cinephone, which was inferior to the Phonofilm process in tone an range. TRAMP TRAMP TRAMP as well as the version of MY OLD KENTUCKY HOME that is in common circulation have “new” animation added to the head that was made during this period. This was also documented in a letter from Walt Disney to Roy when he stopped in to visit Fleischer and learned that they had left. He noted that the Inkwell Studio was in the process of re-releasing some of their old pictures and adding new animation to them. About 15 years ago, I learned that The Library of Congress has the silent version of KENTUCKY HOME, and I saw that the Bouncing Ball footage was identical to that in the sound version. I had purchased the negatives to several of the Song Car-tunes in 2000 and there were slugs in places of the Bouncing Ball footage on that negative. I was able to insert the footage from the silent version, and it matched.

To be sure, the history of the Song Car-tunes is quite muddled due to the haphazard way the films were produced and distributed. I am encouraged that more information is coming out after nearly 100 years, but time is precious because in my experience with this, several of the original negatives were found to be in states of shrinkage, requiring $3,000 each to restore, and others such as the original OH HOW I HATE TO GET UP IN THE MORNING having deteriorated as of 2003.

For the record, I had some experience working with the deForest Phonofilms, and I go into a full account of Song Car-tunes history in my book, THE ART AND INVENTIONS OF MAX FLEISCHER: AMERICAN ANIMATION PIONEER.