By the 1929-30 season, almost every element of a weekly theater program had found its voice. The last refuge for silent pictures was in the Saturday Matinee. Budget Westerns and serials would not acquire tracks until 1930. Cartoons were already finding their voice, following the lead established by Walt Disney. The one and two reel comedy shorts were already talking, or at least being musically scored. And of course, features were becoming thick on the ground. Even the Western, when given an A-level budget, was beginning to be heard, in such films as Fox’s In Old Arizona, Paramount’s The Virginian, and Universal’s Hell’s Hinges. The Fleischer brothers (assisted by additional brother Lou Fleischer, who had a musical background (but who never received screen credit), would move eagerly into this new and exciting medium, though initially keeping life easy for their animators by not instantly leaping into the field of synchronized dialogue. (Even Disney would test the waters a bit before his characters really developed a vocabulary.) Thus Max’s early efforts of the season concentrated upon a return to the “follow the bouncing ball” format, now referred to as “Screen Songs”. The inkwell world of Ko-Ko and Fitz would be abandoned for the time being, never making a full transition to sound during the lifetime of the studio (though receiving a strange revival in the television days from the studios of Hal Seeger). And scripts suited for dialogue would have to wait until the inauguration of a new series banner – but that is a story for another day.

By the 1929-30 season, almost every element of a weekly theater program had found its voice. The last refuge for silent pictures was in the Saturday Matinee. Budget Westerns and serials would not acquire tracks until 1930. Cartoons were already finding their voice, following the lead established by Walt Disney. The one and two reel comedy shorts were already talking, or at least being musically scored. And of course, features were becoming thick on the ground. Even the Western, when given an A-level budget, was beginning to be heard, in such films as Fox’s In Old Arizona, Paramount’s The Virginian, and Universal’s Hell’s Hinges. The Fleischer brothers (assisted by additional brother Lou Fleischer, who had a musical background (but who never received screen credit), would move eagerly into this new and exciting medium, though initially keeping life easy for their animators by not instantly leaping into the field of synchronized dialogue. (Even Disney would test the waters a bit before his characters really developed a vocabulary.) Thus Max’s early efforts of the season concentrated upon a return to the “follow the bouncing ball” format, now referred to as “Screen Songs”. The inkwell world of Ko-Ko and Fitz would be abandoned for the time being, never making a full transition to sound during the lifetime of the studio (though receiving a strange revival in the television days from the studios of Hal Seeger). And scripts suited for dialogue would have to wait until the inauguration of a new series banner – but that is a story for another day.

Old Black Joe (4/5/29, presumed lost) – Another revisit to a number Fleischer had already featured, in a previous talkie for Lee DeForest. We have already dealt with sources of the song in a previous article, so we’ll forego a repetition here.

Ye Olde Melodies (5/2/29, presumed lost) – As the film has never surfaced, we have absolutely no clue what numbers may have been featured here. Maybe something not used before, or maybe just a compilation of numbers left over from the previous Song Car-Tunes. Either way, it may have been the series’ first “package deal”, combining more than one featured tune un the same picture. Anyone with data is invited to comment.

Daisy Bell (5/30/29, presumed lost) – Another revisit to the subject of a prior Song Car-Tune. Again, the reader is referred to prior articles for a run-down of the recordings of the umber.

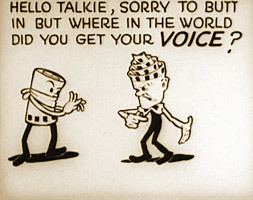

Finding His Voice (6/21/29) – Likely a breakthrough item for the Fleischer catalogue. Max had had a historry of producing instructional/educational cartoons, whether they got a general theatrical release or not. This film, produced by Western Electric, instructs the theater-goer upon the mechanics of exactly what he or she is seeing and hearing from the screen. The film may be a milestone in the amount of dialigue included on screen, including talking, singing, and narration for nearly the entirety of the film (it is doubtful anything equivalent had appeared in the lost Screen Songs). Of course, the mechanics of presenting this are still primitive and rudimentary. Characters often move their mouths with repeated opening and closing lips, while actual lines are post-synced by the voice crew as the completed film is projected. Professor Western, the technological whiz who instructs respective filmstrips Talkie and Mutie on the workings of sound projection, jabbers away at a brisk pace in this manner, even flubbing one line entirely but continuing nonetheless with the lecture, without any attempt at a sound edit. Features the voices of Billy Murray and Walter Scanlon. Interestingly, the speaking voice of Talkie is provided by Murray, yet rhe character sings “Love’s Old Sweet Song” in the voice of Scanlon! When they reach their final number, “Goodnight Ladies”, Scanlon has switched places to provide Mutie’s new voice, while Murray sings his own lines as Talkie.

Finding His Voice (6/21/29) – Likely a breakthrough item for the Fleischer catalogue. Max had had a historry of producing instructional/educational cartoons, whether they got a general theatrical release or not. This film, produced by Western Electric, instructs the theater-goer upon the mechanics of exactly what he or she is seeing and hearing from the screen. The film may be a milestone in the amount of dialigue included on screen, including talking, singing, and narration for nearly the entirety of the film (it is doubtful anything equivalent had appeared in the lost Screen Songs). Of course, the mechanics of presenting this are still primitive and rudimentary. Characters often move their mouths with repeated opening and closing lips, while actual lines are post-synced by the voice crew as the completed film is projected. Professor Western, the technological whiz who instructs respective filmstrips Talkie and Mutie on the workings of sound projection, jabbers away at a brisk pace in this manner, even flubbing one line entirely but continuing nonetheless with the lecture, without any attempt at a sound edit. Features the voices of Billy Murray and Walter Scanlon. Interestingly, the speaking voice of Talkie is provided by Murray, yet rhe character sings “Love’s Old Sweet Song” in the voice of Scanlon! When they reach their final number, “Goodnight Ladies”, Scanlon has switched places to provide Mutie’s new voice, while Murray sings his own lines as Talkie.

Another notable tecnological point that probably went over the heads of the audience was Professor Western’s comment to Mutie, “You’be neen running at 60. We’ll have to pep you up to 90″ (referring to the change in film speed from silent to sound in feet per minute). Songs include “Ever Since the Movies Learned to Talk”, heard over the opening titles. Billy Murray cut it commercially for Edison and Harmony/Velvet Tone/Diva. Irving Kaufman covered it for Banner, Domino, and the other Plaza music labels. Walter O’Keefe made a recording for Victor, but for unkmnown reasons it was never issued. We also get “Just Anothe Kiss”, a gentle waltz recorded by George Olsen and his Music for Victor, “Love’s Old Sweet Song”, performed by Loiuise Homer on Victor red seal around 1920. Maurice Cambois on Aeolian Vocalion Red Record approx. 1920; Edward Cromwell (pope organ) on American Regal circa 1927, Deanna Durbin on Decca from 1942, and Bob Hannon on Majestic approx. 1947, and “Goodnight, Ladies” an old chestnut, recorded by Conway’s Band for Victor circa 1916, revived in the ‘30’s by Andre Kostelanatz in a symphonic treatment for Brunswick, the 40’s by The Sportsmen on Capitol, the Ames Brothers aas part of a “Good Fellows Medley” on Coral in the 1950’s, the Fred Warren Choristers (how shameless a sound-alike can you get to Fred Waring?) on Superior in the 1950’s and played against a new number (“Pick a Little, Talk A Little”) as counter-melody in the Broadway Score of “The Music Man” by the Barber shop quartet, The Buffalo Bills, on both the Broadway Cast and film soundtrack LP’s.

Mother Pin a Rose on Me (7/6/29 – presumed lost). The song is from 1906, recorded at the time by Billy Murray for Victor. Little other recording seems to have taken place – so it is again possible this was a screen opportunity for Billy Muttay to re-record a past success, as he was definitely on the Fleischer lot by this time.

Dixie (8/17/29, presumed lost). Another revisit to a song used in the earlier silent series. Presumably by this time, when it appears that Paramount was insisting that Screen Songs have some actual minimal cartoon content, rather than simply provide the bouncing ball accompaniment to slides, we can guess that some footage of the deep South was the topic of the animated segment. This could easily have resulted in a considerable amount of poitical incorrectness, as was the habit of most animators of the day touching on Southern subjects. The song’s recorded history has already been covered in the discussion of the silent film in a prior article.

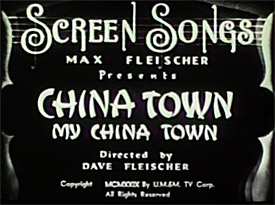

Chinatown, My Chinatown (8/29/29). At last, we encounter a survivor full talkie, the earliest to known to have made the TV distribution package of UM&M and NTA. Gags are set in a chinese laundry. A central gag has one of the Chinamen eating a bowl of chop suey, and somehow getting articles of the laundry mixed inti the meal he consumes. Another Chinaman engages the first in a battle, in which they “fence”, using their queue hairstyle as swords. The song is from 1915, recorded at the time by the American Quartet for Victor. However, the Quartet’s lead singer (Murray again), curiously does not appear to get involved in the singing on the track of this film. The song would later become a favorite for jazz musicians, receiving many revivals and some recordings within a few years of the film. Fletcher Henderson recorded the number for Columbia in 1930. Red Nichols followed for Brunswick in 1930, Louis Armstrong in 1931 for Okeh (we will encounter some of his arrangement for this piece again in the later Betty Boop classic, “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You”. The Mills Brothers would give it a vocal romp in 1932 for Brunswick. Ray Noble’s American band would perform a 1935 version for Victor. Harry Roy in England would make a medley by combining the piece with “Limehouse Blues” for Parlophone, and imported here on Decca. Tommy Dorsey and his Clambake 7 performed a small-jazz version on Victor. Louis Prima gave it an upbeat treatment for Brunswick in the 1930’s. then a swing sound for Majestic in the 1940’s. Lionel Hampton would rename the piece “China Stomp” while playing two-finger piano on a late 1930’s Victor side. Slim Gaillard and Slam Stewart (who had the unique gimmick of bowing his bass while humming an octave higher than what he is playing) gave the number their unique sound for Vocalion in the late 1930’s. Jack Teagarden performed it on Commodore. Reginald Forsythe in England would attempt to replicate at the keyboard the style of an earlier hit version, in a side nominally titled “Homage to Armstrong” for Decca England. Al Jolson with Four Hits and a Miss and Matty Malneck performed a late 1940’s verson on Decca. Harpist Robert Maxwell (the Les Paul of the Harpo Marx trade) would perform it in sprightly fashion in the 50’s for Mercury. Disney’s home-grown Firehouse Give Plus Two would wax it in the 1950’s for Good Time Jazz. Chet Atkins would also get his fingers on it, with his “Galloping Guitar”, for RCA Victor.

Chinatown, My Chinatown (8/29/29). At last, we encounter a survivor full talkie, the earliest to known to have made the TV distribution package of UM&M and NTA. Gags are set in a chinese laundry. A central gag has one of the Chinamen eating a bowl of chop suey, and somehow getting articles of the laundry mixed inti the meal he consumes. Another Chinaman engages the first in a battle, in which they “fence”, using their queue hairstyle as swords. The song is from 1915, recorded at the time by the American Quartet for Victor. However, the Quartet’s lead singer (Murray again), curiously does not appear to get involved in the singing on the track of this film. The song would later become a favorite for jazz musicians, receiving many revivals and some recordings within a few years of the film. Fletcher Henderson recorded the number for Columbia in 1930. Red Nichols followed for Brunswick in 1930, Louis Armstrong in 1931 for Okeh (we will encounter some of his arrangement for this piece again in the later Betty Boop classic, “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You”. The Mills Brothers would give it a vocal romp in 1932 for Brunswick. Ray Noble’s American band would perform a 1935 version for Victor. Harry Roy in England would make a medley by combining the piece with “Limehouse Blues” for Parlophone, and imported here on Decca. Tommy Dorsey and his Clambake 7 performed a small-jazz version on Victor. Louis Prima gave it an upbeat treatment for Brunswick in the 1930’s. then a swing sound for Majestic in the 1940’s. Lionel Hampton would rename the piece “China Stomp” while playing two-finger piano on a late 1930’s Victor side. Slim Gaillard and Slam Stewart (who had the unique gimmick of bowing his bass while humming an octave higher than what he is playing) gave the number their unique sound for Vocalion in the late 1930’s. Jack Teagarden performed it on Commodore. Reginald Forsythe in England would attempt to replicate at the keyboard the style of an earlier hit version, in a side nominally titled “Homage to Armstrong” for Decca England. Al Jolson with Four Hits and a Miss and Matty Malneck performed a late 1940’s verson on Decca. Harpist Robert Maxwell (the Les Paul of the Harpo Marx trade) would perform it in sprightly fashion in the 50’s for Mercury. Disney’s home-grown Firehouse Give Plus Two would wax it in the 1950’s for Good Time Jazz. Chet Atkins would also get his fingers on it, with his “Galloping Guitar”, for RCA Victor.

Goodbye, My Lady Love (8/31/29, possibly lost) – The song is from 1904, and was written by Joe Howard. Harry MacDonough recorded it for Victor’s Monarch series, and Arthur Collins covered it for American. Joe Natus also recorded it for Zon-o-Phone. Russ Morgan would revive the number for a recording on Decca in the 1930’s. In the 1940’s Joe Howard himself would get to record it on DeLuxe, in conjunction with his “comeback” as the host of the “Gay 90’s Revue” on radio, and subsequently on early TV (Joe would also receive reflected fame from a bio picture produced for Fox, “I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now”). The song would have an additional life as part of a finale medley on two related LP’s devoted to ole-time minstrelsy – “Gentlemen, Be Seated” on Epic, and “A Complete Authentic Minstrel Show” on Somerset.

Here’s Joe singing his hits on a 1953 George Jessel Show kinescope…

Smiles (7/24/29, presumed lost) – The song is from 1918. Joseph C. Smith recorded it for Victor, and Earl Fuller’s Rector’s Novelty Orchestra covered it for Columbia. Prince’s Band also waxed it for Columbia. Victor also had a blue seal version by tenor Lembert Murphy. Claude Thornehill would revive it for Columbia in the early 40’s. Ben Light included it in his endlesss piano repetoire on Tempo. And Crazy Otto countered with his own version on Decca. Jo Stafford and Dave Lambeert would team up for a vocal version on Capitol.

My Pony Boy (10/21/29, presumed lost). This film was releasesd only a few days before Wall Street laid its famous egg – though it is doubtful its content would have any relationship to such condition. The song is from 1909 and was recorded at least three times by Ada Jones, for Victor and Columbia discs and for Edison Cylinders. It received one revival by Freddie Fisher for Decca in the late 1930’s, then became relegated to a kiddie record staple for Little Golden, Peter Pan, etc. Here’s a beautiful recording of the song by Helen Traubel:

Next Time: The birth of the Talkartoon

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

Smiles is still around, thankfully: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=km71HODPQow

I’m very familiar with the score to “The Music Man”. “Goodnight, Ladies”, sung by the Buffalo Bills in tandem with the women’s gossip chorus “Pick a Little, Talk a Little”, is an example of a Broadway counterpoint song, in which two songs of contrasting character (but with identical chord changes) are sung in succession, then combined into an harmonious whole. A second example from the same show is “Lida Rose”, sung by the Buffalo Bills along with “Will I Ever Tell You”, sung by Marian the Librarian. Near the end of Act II, the march “Seventy-Six Trombones” is combined with the lullaby “Goodnight, My Someone” — not in counterpoint, but with alternating phrases. The two songs have exactly the same melody, but vastly different tempi and moods.

Irving Berlin, who inspired more Fleischer and Famous Screen Songs than any other living songwriter, wrote a counterpoint song for his first musical comedy “Watch Your Step” of 1914: “Play a Simple Melody”, combined with the jazzy “Musical Demon”. This was the first Broadway musical written by a Tin Pan Alley songwriter, and with it Berlin proved that he could swim with the big fishes. Counterpoint songs became a regular feature in his musicals; often he would write an original song set in counterpoint with a patriotic standard like “The Star Spangled Banner”, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”, or “The Stars and Stripes Forever”.

I doubt that any counterpoint songs were ever adapted into the Screen Songs series. Two separate bouncing balls would have been hard for the audience to follow.

In the Van Beuren Aesop’s Fables cartoon “Laundry Blues” (1930), a male vocal quartet sings “Chinatown, My Chinatown” in faux-Chinese nonsense syllables. They’re pretty good — but they’re no Buffalo Bills!

Imagine going into a restaurant ordering a dinner and seeing only the main course arrive. That is what we get today. The rich experience people once had going to the movies with all these fabulous short films is no more.

Counterpoint songs might have been animated with two bouncing balls, using a different color for each ball and each set of lyrics. Of course the hues in the pre-three strip Tech era would have had to have been green and orange, which would have worked visually, yet presenting a challenge for the average audience to follow. Except for a small percentage of people who just might be inspired by such a presentation, arguably going on to change musical history at some point.

It’s fun to notice on a few of the early Screen Songs in the NTA TV package a “Track & Disc Sound Print” card on the film leaders (beginning, end or both) with Paramount Screen Song at the bottom. Guessing that this does not include the mountain/star image of the Paramount logo it was left on… presuming the local TV stations’ projectionists do not show it. Of course back in the 1950’s that was not always the case.

Actually, the “Track and Disc” card did not disappear from Hollywood when disc soundtracks were long out of vogue. I have a home movie print of excerpts from “Singin’ in the Rain” with Gene Kelly that still uses the card on its original projectionist’s leader. One might have thought it presented an opportunity for an “in” joke, since the film was about early talkies – but I doubt anyone thought such an idea through so far, and it was more likely the processing labs just never abandoned the style.

So, nine screen songs in 1929, with two survivors. Guess that is about par for the course. I think I would rather see these missing cartoons than any missing feature from this time frame (excepting Gold Diggers of Broadway of course).

UCLA’s online catalog lists a 16mm print of My Pony Boy in their holdings: https://cinema.library.ucla.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=87133

How would I be able to gain access to that, and some other screen songs that have available. I checked the full catalog of Screen Songs and saw that they had a lot of 35MM/16MM films available