The Popeye cartoons of the 1940’s are both similar to and different from the cartoons that preceded them. They seem to have been less likely to include quotes from popular songs being published by Famous Music. And they don’t seem to rely as heavily on the triangle of Popeye, Olive Oyl and Bluto. The fact that they had to import Pinto Colvig from California to do Bluto’s voice suggests they could not find local talent in Florida good enough to rise to the level of William Pennell or Gus Wicke. (When the studio closed and the remaining personnel moved back to New York, they found Jackson Beck, who gave them what they needed.) As many of the last Fleischer Popeyes have no new song material, this article will overlap into some of the earliest produced by Famous Studios upon Paramount calling in the debts of the Fleischers and taking over. In many respects, the transition between the two products progressed quite seamlessly, and one wonders if the distributors even took notice of the internal upheavals taking place behind the scenes that would put Max and Dave out on their ear.

The Popeye cartoons of the 1940’s are both similar to and different from the cartoons that preceded them. They seem to have been less likely to include quotes from popular songs being published by Famous Music. And they don’t seem to rely as heavily on the triangle of Popeye, Olive Oyl and Bluto. The fact that they had to import Pinto Colvig from California to do Bluto’s voice suggests they could not find local talent in Florida good enough to rise to the level of William Pennell or Gus Wicke. (When the studio closed and the remaining personnel moved back to New York, they found Jackson Beck, who gave them what they needed.) As many of the last Fleischer Popeyes have no new song material, this article will overlap into some of the earliest produced by Famous Studios upon Paramount calling in the debts of the Fleischers and taking over. In many respects, the transition between the two products progressed quite seamlessly, and one wonders if the distributors even took notice of the internal upheavals taking place behind the scenes that would put Max and Dave out on their ear.

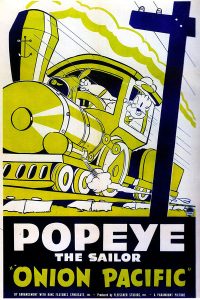

“Onion Pacific” (5/24/40) – Title playing upon the 1939 Cecil B. DeMille success for Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea as “Union Pacific”, there is to be a race between Onion Pacific (represented by Popeye) and Sudden Pacific (represented by Bluto), for a lucrative state franchise for the railroad. Meanwhile, Olive has promised to give the winner a kiss. Bluto has to resort to sabotage to try to win, but Popeye hangs on (with the help of Olive, who proves the link between the two trains as they each balance on one rail of a trestle that will allow only one train to pass). After Popeye downs the green leafy stuff, he rebuilds his train into a modern streamliner, its high fins catching the finish line banner as he passes under. Popeye wins the race and gets the kiss. Songs: “We’re All Together Now” (the march from the Gulliver’s Travels score. I believe the only commercial recordings were Victor Young’s within the album set produced for Decca records of the feature’s score, and also within a medley performed by Ambrose on British Decca.

Click audio embed below – “All Together Now” starts at 2:40

“Nurse Mates” (6/26/40) – Popeye and Bluto converge on Olive’s apartment, both wanting to take her to the movies. Instead, they wind up having to mind Swee’pea. Bluto’s techniques of baby-sitting are what you’d expect, while Popeye’s are more genteel. Swee’pea eventually crawls out of the window of the upper story apartment, but eludes the boys to return to his crib on his own, to Popeye’s surprise. Songs: “You’re a Sweet Little Headache”, from the Bing Crosby film, Paris Honeymoon (embed below), written by Leo Robin and Ralph Rainger, the house composers for Paramount features. Crosby would record the number for Decca. Benny Goodman covered it for Victor, Artie Shaw with Helen Forrest for Bluebird, Red Norvo for Brunswick, and Nan Wynn in a vocadance version for Vocalion. The Goodman version was remembered for inclusion on a phonograph record in a sequence of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

“My, Pop, My Pop” (10/19/40) – The first comeback for Poopdeck Pappy, and the first of several subsequent Pappy pictures to come. In his usual meddling mood, Pappy insists he is an expert at building ships, and attempts to interfere with Popeye’s construction of a new craft. Popeye settles the dispute by splitting the project in two, each sailor to construct one side of the vessel. Popeye’s side looks ship-shape and in Bristol fashion, but Pappy’s is a disheveled mess. Out comes the spinach, and Popeye goes to work fixing Pappy’s side while the ancient mariner snoozes in exhaustion. Popeye’s efforts “Gaslight” Pappy into thinking he’s done a good job, allowing him to leave happy and boastful as ever. Songs: “(I’m Popeye’s) Poopdeck Pappy”, an original which became a theme song for the character’s later appearances.

“I’ll Never Crow Again”.(9/17/41) – Olive is washing dishes in her kitchen, looking out the window at her vegetable garden – which she discovers is infested with hungry crows. Popeye is called to try to scare the birds away, but the crows are persistent. A gag is lifted from Warner’s “Porky’s Spring Planting”, as a crow admires the wardrobe of Popeye’s scarecrow with the comment “Hmm, nice material”, then dons the suit and blows a puff of cigar smoke in Popeye’s face. Olive is much amused by Popeye’s futile efforts, adding to his frustration. Eventually, Popeye brings out the old rifle, but without his spinach, his shots aren’t that accurate. Olive’s continued laughter brings Popeye to the breaking point – causing him to set up Olive as the scarecrow – the only idea that works! Songs: “Listen to the Mocking Bird”, written in 1851. The earliest recorded version I’ve found is by Alma Gluck on Victrola Red Seal in 1908. Sybil Sanderson Fagen recorded it as a whistling solo on Columbia. A swing version was issued in the 30’s by Jimmy Dorsey and his Orchestra. Dinah Shore performed it as an aircheck in the 1940’s with a new lyric. And there was another whistling version by Brother Bones and his Shadows (of Harlem Globetrotters’ “Sweet Georgia Brown” fame in 1948 on Tempo.

“You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” – (3/26/42) – Popeye, on board a patrol boat, spots a Japanese fishing boat, populated by a small crew of Japanese who claim they want peace (even offering a booby-trapped treaty). Needless to say, it’s a subterfuge, and the fishing boat is merely a decoy on the conning tower of a semi-submersible Japanese battle-wagon. Popeye’s spinach-powered tactics promise “V-‘ll show ‘em”, as he extracts cannon like so many loose teeth, demolishes the enemy vessel into scraps like it was made of paper (due to its label revealing it was, after all, made in Japan), and causes its captain to commit Hari-Kari with a meal of firecrackers, washed down with gasoline. Songs: “Light Cavalry Overture”, Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song”, and the title song, one of the fairly early Tin Pan Alley reactions to Pearl Harbor. Recordings of it included Orrin Tucker on Columbia, Carl Hoff on Okeh, and Dick Robertson on Decca.

“Alona on the Sarong Seas” (9/11/42) – Don’t forget how big a star Dorothy Lamour was at Paramount. Popeye and Bluto are in “fighting pals” mode, stationed in the South Seas, and wind up on the Island of Woo-Woo, where they met the fabled Princess Alona (Olive), saronged and water-skiing, then taking a plunge off a high cliff (which temporarily leaves her sarongless underwater, until she retrieves the garment in modesty). :The sailors pursue, but the princess’s parrot warns, “If you should harm a hair of her head, the fire mountain says, you shall be dead – or even woise!” Bluto ignores the warning as so much hooey, but by the end of the film, Popeye catapults him into the fire mountain, butt-first, to satisfy the fire spirits. The film ends in an “all a dream” mode, with Popeye still mooning over the princess’s photo aboard ship, and Bluto crowning him with a ukulele. (Have the writers been watching too many Gandy and Soupuss episodes?) Songs: “Aloha Oe” and “(I’m) Too Romantic”, from Road to Singapore, introduced by Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. Bing recorded it for Decca. Tommy Dorsey also got the song for Victor. Glenn Miller landed it for Bluebird. Everett Hoagland’s orchestra would also cover it on Decca – he had a stylized sweet band that later became popular in Mexico.

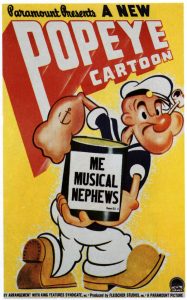

“Me Musical Nephews” (12/25/42) – What a Christmas present! Sprightly music, and sprightly visuals too. Popeye is sitting uneasy in his easy chair, listening to his nephews practice the piece, “Sweet and Low”. From Popeye’s reactions, the music is neither very sweet, nor very low, Popeye decides its time for all to go to bed. He hastily improvises a pointless bedtime story from snippets of famous fairytales, leaving the nephews feeling gypped. The film borrows several gag elements from Fleischer’s early Color Classic, “The Kids In the Shoe”, including the kids cheating before their bathroom mirrors on their nightly hygiene routines (brushing the teeth of their mirror reflections rather than their own, etc.,), and being sent to bed without wanting to. Like the predecessor cartoon, they begin improvising with such things as loose bedsprings, brass tubing of their bedsteads, and other objects around the house to create makeshift musical instruments (even out of a Flit gun), resulting in an impromptu jam session. Popeye can’t figure where the music is coming from, and p lays a riotous game of hide and seek to attempt to catch the boys in the act. Sound effects work is excellent in this sequence (with lightning cuts between music and snoring), as well as in an offscreen shot where Popeye himself tries to ready for bed, with every sound effect of a nightly routine piled one upon another in a matter of seconds – editing worthy of Treg Brown at Warner Brothers. Eventually, Popeye can take it no more, and sees as his only chance for sleep an escape through the camera iris of himself and his bed, closing the iris to black behind him to shut out the music. But the boys’ melodies follow him even past the black void, into the very theater where we are watching the picture, as the nephews appear on stage, and Popeye reacts with conniption fits as he goes insane, up the aisle and out of the theater. Songs: “Sweet and Low”, an early lullaby. Elsie Baker recorded it on Blue Seal Victor in the 1920’s. Art Hickman’s Orchestra also performed it on acoustic Columbia An early “Brass Quartette” version was issued on “unbreakable” cardboard Nicole records from Britain around 1904. Also featured is “Bugle Call Rag”, first recorded by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings in 1922 on Gennett. It was later done by Ted Lewis on Columbia. Cab Calloway also did an early 30’s version on Brunswick. Duke Ellington had an arrangement in 1932 for Victor. It was performed in swing style by Benny Goodman on both royal blue Columbia and later on Victor. Bobby Hackett had a version on Vocalion. Harry Roy in England recorded it for Parlophone, also issued here on Decca. Andre Kostelanatz performed a concert version for Brunswick in 1937. Glenn Miller had his own version on Bluebird. The number became one of jazz’s evergreens, culminating in a “Metronome All Stars” session of noted leaders and sidemen on Victor in 1941. The Modernaires tried a vocal version for Coral in the 1950’s. It was lampooned in a minor key by Mickey Katz on Capitol in the 1950’s, as “Bagel Call Rag.”

“Me Musical Nephews” (12/25/42) – What a Christmas present! Sprightly music, and sprightly visuals too. Popeye is sitting uneasy in his easy chair, listening to his nephews practice the piece, “Sweet and Low”. From Popeye’s reactions, the music is neither very sweet, nor very low, Popeye decides its time for all to go to bed. He hastily improvises a pointless bedtime story from snippets of famous fairytales, leaving the nephews feeling gypped. The film borrows several gag elements from Fleischer’s early Color Classic, “The Kids In the Shoe”, including the kids cheating before their bathroom mirrors on their nightly hygiene routines (brushing the teeth of their mirror reflections rather than their own, etc.,), and being sent to bed without wanting to. Like the predecessor cartoon, they begin improvising with such things as loose bedsprings, brass tubing of their bedsteads, and other objects around the house to create makeshift musical instruments (even out of a Flit gun), resulting in an impromptu jam session. Popeye can’t figure where the music is coming from, and p lays a riotous game of hide and seek to attempt to catch the boys in the act. Sound effects work is excellent in this sequence (with lightning cuts between music and snoring), as well as in an offscreen shot where Popeye himself tries to ready for bed, with every sound effect of a nightly routine piled one upon another in a matter of seconds – editing worthy of Treg Brown at Warner Brothers. Eventually, Popeye can take it no more, and sees as his only chance for sleep an escape through the camera iris of himself and his bed, closing the iris to black behind him to shut out the music. But the boys’ melodies follow him even past the black void, into the very theater where we are watching the picture, as the nephews appear on stage, and Popeye reacts with conniption fits as he goes insane, up the aisle and out of the theater. Songs: “Sweet and Low”, an early lullaby. Elsie Baker recorded it on Blue Seal Victor in the 1920’s. Art Hickman’s Orchestra also performed it on acoustic Columbia An early “Brass Quartette” version was issued on “unbreakable” cardboard Nicole records from Britain around 1904. Also featured is “Bugle Call Rag”, first recorded by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings in 1922 on Gennett. It was later done by Ted Lewis on Columbia. Cab Calloway also did an early 30’s version on Brunswick. Duke Ellington had an arrangement in 1932 for Victor. It was performed in swing style by Benny Goodman on both royal blue Columbia and later on Victor. Bobby Hackett had a version on Vocalion. Harry Roy in England recorded it for Parlophone, also issued here on Decca. Andre Kostelanatz performed a concert version for Brunswick in 1937. Glenn Miller had his own version on Bluebird. The number became one of jazz’s evergreens, culminating in a “Metronome All Stars” session of noted leaders and sidemen on Victor in 1941. The Modernaires tried a vocal version for Coral in the 1950’s. It was lampooned in a minor key by Mickey Katz on Capitol in the 1950’s, as “Bagel Call Rag.”

“Spinach Fer Britain” (1/22/23) – Popeye is delivering a shipment of spinach to the British Isles, which at the time were subject to blockade by the Nazi U-boats. One such craft (known as an “unterseebot”, but which Popeye calls a “subterine”) gets inside the hull of Popeye’s vessel, with shots from its cannon making lines of bullet holes in Popeye’s hull. Popeye thinks he has a woodpecker as a stowaway. Popeye eventually makes short work of the “sour Krauts”, and makes his delivery through another sound-effect laden London fog, right to the steps of the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street.” Song: “Rule Brittania”. Alan Turner recorded an early acoustic Victor vocal. Frances Alda recorded another version for Victrola Red Seal in the early teens. The Grand Metropol Band recorded an acoustic version in England around 1911 for Pickofall. A version as “The King’s Military Band” appeared in England on Regal, which might possibly be an imported American recording under a false name. The Royal Chorale Society performed an electrical version for HMV. Sir Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony Orchestra included it in a medley for HMV. A late performance appeared as a 45 rpm single by the Band of the Grenadier Guards on London records.

Oh heck, let’s just end this post by watching the whole cartoon:

Next Time: miscellaneous “antics”.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

“You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” was also recorded by Spike Jones as something of a follow-up to “Der Fuehrer’s Face”. When the Japanese sailor in the cartoon blows the bugle, we hear a recording of Japanese komagaku music, one of several forms of gagaku court music (and the only one that doesn’t use stringed instruments). There seem to be only three instruments playing: a komabue or small flute, a shoko or gong, and some variety of small drum. I have a feeling that the studio examined a number of stock recordings of traditional Japanese music until they found one that they felt would be maximally discordant and unpleasant to American audiences.

“Rule, Britannia” was originally the finale to Thomas Arne’s opera “Alfred” (on the life of King Alfred the Great). Beethoven wrote a set of variations on it for solo piano, as well as a set of variations on “God Save the King”, and he incorporated both tunes into his worst piece of music, “Wellington’s Victory”. Beethoven’s music was very popular in Great Britain during his lifetime (although he never went there), and the works he composed to pander to English audiences are a far cry from his greatest masterpieces.

Another wartime Popeye cartoon, “Blunder Below”, makes ample use of a familiar tune that I don’t recall hearing in other Fleischer cartoons: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”, or “Baa Baa Black Sheep”, or possibly it’s meant to be the A-B-C song because the first scene takes place in a classroom. Some of my music teachers told me that this melody was written by Mozart, but that is untrue. Mozart did compose a set of twelve variations on that theme, but it was already a well-known French folk song by then.

I accept that you can choose to skip over any cartoons you wish in this series of articles, but would you be able to identify for me the conga used in “Kicking the Conga Round”? I’ve wondered about that for years. It’s a very catchy tune.

Even as a youngster watching these late b&w’s on TV, I thought “I’m Popeye’s Poopdeck Pappy” was the same melody as “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” until I figured out they came from two completely different studios.

Loved all the cartoons —— but, Gad, Bing Crosby was great!

I have enjoyed this romp through the Fleischer/Paramount cartoons, but I would like to back up just a bit. Who owns the early screen song negatives/prints? Where are they? Do they even exist anymore? A mediocre print of “”Mr. Gallagher and Mr. Shean” showed up on YouTube recently, and I thought it was a cause for rejoicing! So why can’t we see decent prints?

You must be new here – or a younger person. This has been the issue for decades.

Paramount Pictures has the early Screen Song nitrate negatives. They are being cared for at the UCLA Film & Television Archive in Valencia California.

We haven’t seen decent prints because Paramount had sold those shorts to TV distributors (at first U.M.&M. then NTA, later Republic) who made 16mm prints that went out to TV stations in the 1950s and 60s. Paramount acquired Republic in the 1990s so Paramount today controls those master film elements. There has been no financial incentive for anyone to make new prints or restore these films – despite their historic nature and fan interest.

Because it can cost anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000 to restore one of these – there is little movement to actually protect these films. A group I am a part of – ASIFA-Hollywood – donates money annually to UCLA to help save a few cartoons in their collection. A few years ago we restored DINAH with the Mills Brothers – and several others. It’s a sad situation.

I hope this answers your questions.

You did. Thank you. It does impress me that so much money is spent on restoring cartoons like the Flip the Frog cartoons. If a minimum of 10,000 dollars is spent on each one of these, then a set is a significant financial investment.

As a POPEYE fan, there is much that still confuses me about who did what at Fleischer and Famous Studios. Wasn’t Pinto Colvig working for a time at Fleischer’s around the late ’30s into the early ’40s? I don’t think he had to be “imported”?!? I know I’ve seen a picture or two of Colvig with Jack Mercer and Margie Hines. Jack Mercer’s widow Virginia told me that her husband – from what he told her – got along very well with Pinto Colvig and enjoyed working with him. This makes perfect sense, as both men were VERY musically inclined!

There’s at least one “Bluto” between Pinto Colvig and Jackson Beck that I know very little about – Jack Berry, I think is the name. He did a couple of stints as “Bluto” in cartoons like WE’RE ON OUR WAY TO RIO. He did a pretty good job – especially with his singing voice – as far as I’m concerned. I can’t think of the cartoon at the moment, but Steve Stanchfield and I are pretty convinced that Jack Mercer voiced “Bluto” in at least one POPEYE cartoon as well!

I don’t know exactly when Jackson Beck did voice work for Famous, but his first POPEYE cartoon as “Bluto” was released in 1944.

I believe the title is THE ANVIL CHORUS GIRL. Sorry, I forgot it for a moment. And … I think the guy who voiced “Bluto” in WE’RE ON OUR WAY TO RIO was Dave Barry. Sorry!