In 1929, the production of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons moved to the backlot of Universal Pictures, an opening salvo in the shift of an industry from New York to Hollywood. Walter Lantz scoured Manhattan and the boroughs looking for good animators. He was competing with Walt Disney, who was doing the same. The rush was on to sign top talent and to hasten them aboard westbound trains.

One of the biggest fish to catch, the prodigious animator Bill Nolan, was signed by Lantz. The deal was sweetened by an agreement in which they shared a producing credit on all Universal Cartoons. Like many of his New York peers who recognized how the times were changing, Nolan left the big city behind and began a second phase of his career in sunny California.

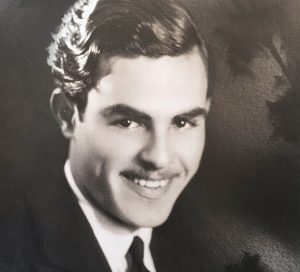

He was soon to cross paths with Manuel Moreno, who at that point was an assistant animator on the Oswald series at the Winkler studio. Moreno had emigrated with his family from Nacozari de García, a mining town in Sonora, Mexico, and settled in the Huntington Park neighborhood of Los Angeles in 1920. At a young age, he had already shown himself to be confident and resourceful. With a drawing table set up at his parents’ house, he began to earn money through his artwork.

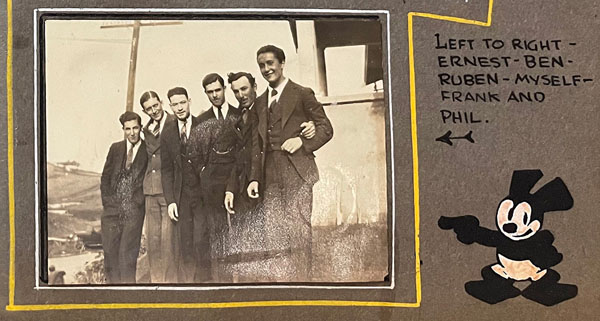

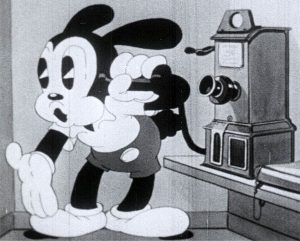

He was hired by producer George Winkler in 1928. A photo in a family scrapbook shows him the same month he was hired. Although the picture seems to be a group of friends from his church, friends who were unaffiliated with cartoons, Moreno painted little versions of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in the margins, a character he’d just begun to draw at the studio. The pace of this series would be unrelenting for most of his next ten years, with more and more rabbits spun from his pencil.

Oswald pointing to a photo, Moreno in the center, dated March 8, 1928

Like many kids of that era, Moreno was fascinated with silent movies and cartoons, but the means to learn more about animation were limited. He applied himself during his teenage years by drawing comic strips and illustrations. His work appeared regularly in a children’s section of the Los Angeles Times known as The Junior Times. To further his artistic skills with lessons, he then took a mail-order course.

In an interview with Milton Gray in 1978, he discussed the importance of taking this course and that it later made Moreno feel like “Bill Nolan was God Almighty. I learned animation from the correspondence course that he wrote for the W.L. Evans School of Cartooning. I think it was in Cleveland, Ohio.” Moreno clarified which part exactly he attributed to his co-worker. “The last lesson was How To Make Animated Cartoons by Bill Nolan.”

The confirmation of his authorship is significant because the Evans course does not acknowledge the last lesson was by Nolan. In fact, the title page would suggest otherwise: “Copyright 1921 by W.L. EVANS” was the only attribution. Moreno did not indicate if, when he completed the course in 1926, he knew the last lesson was actually ghostwritten by Bill. It would be easier to presume he didn’t know this in 1926, but that word had spread around to animators when Nolan arrived on the Universal lot at the end of the decade.

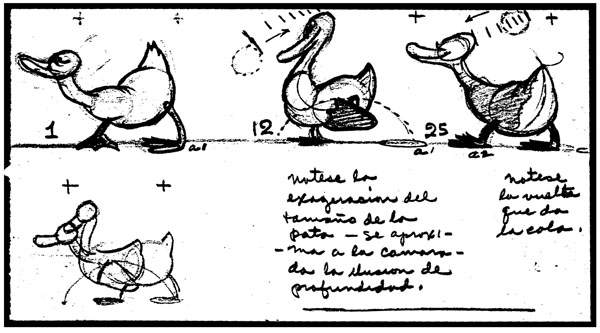

Animation analysis by Moreno showing how exaggerated movements can give an illusion of screen depth.

There’s some evidence they called it “Nolan’s course” as a shorthand reference. At the very least, How To Make Animated Cartoons was a clunky title to use in conversation. When this lesson was added to the course, it provided a plain-spoken manual on starting a home studio. Moreno said, “The lesson told you how to make your own equipment, how to photograph, and to me, it was the only source of information.”

Much of the spotlight shining today on early animation instruction goes to E.G. Lutz’s 1920 book, Animated Cartoons, in part because it holds a cherished place in Disney lore, but this testimony from Moreno shows that for others the foundational text was by Nolan. It also offered some basic instruction in animation techniques, although more sparingly than Lutz did.

This provides context for why the California artists may have regarded Nolan’s arrival with some degree of awe. Assuming that Moreno was not the only Universal Cartoons staffer who had taught himself through the Evans course, this enabled a group introduction to their teacher. Moreno revealed, “I couldn’t believe it! I just stopped short of dusting his chair before he sat in it.”

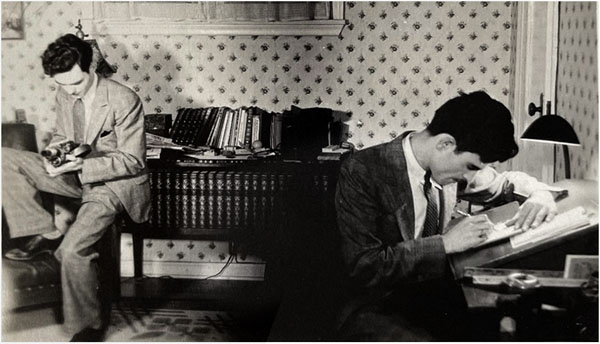

A double exposure reveals Manuel Moreno deep in cinematic dreams.

In fact, the admiration was mutual. A short time after his arrival, Nolan pulled Moreno from Lantz’s staff and had him assigned to work directly for him. He joined Chet Karrberg, who came over from New York along with Bill, where they’d been working partners. Because of the speed at which Nolan went through drawings, he needed two assistants. “Then when I saw how he worked,” recalled Moreno, “I thought I would never be able to animate that well or fast.”

Nolan adhered to the old New York style of animation. He roughed in a lot of circles and drew all his frames straight-ahead, not key poses from which his assistants would then apply the in-betweens. According to Moreno, it was only when Bill had finished a long sequence of very rough drawings that he then went back over just a few of them, to add points of reference for Chet and Manuel.

Moreno knew there was another method taking shape among Hollywood animators. For instance, during his year at Winkler, he admired the talent of Hugh Harman, who was in the vanguard of those adopting the pose-to-pose technique. Yet there was much to learn from Nolan’s raw intuition of movement. Moreno would be given stacks of his roughs, usually “150 or so drawings,” and it was his job to add every detail and bring the characters to life in finished pencil lines.

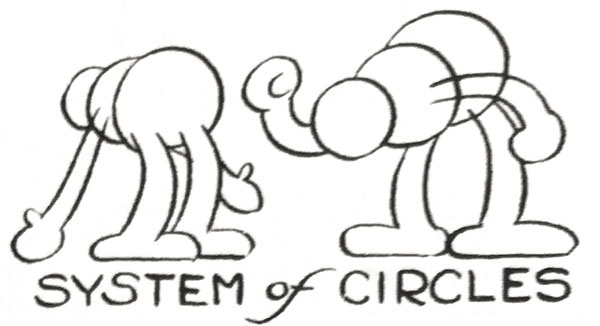

One section in How To Make Animated Cartoons was titled System of Circles. This provided a clear insight into Nolan’s method, how he used three circles (head, torso, buttocks, in his words) with connecting lines to convey the gestures and poses. “Loops” were drawn to indicate the feet and hands. This was presumably how the sketches looked that Moreno received. If his education began with a secret lesson at the end of the Evans mail-order course, then it continued here working directly for Nolan at Universal.

The two assistants got to watch his preliminary test reels. Perhaps this helped them refine the character animation during cleanup, but the main purpose was for Nolan to evaluate his own work. Here is how Moreno described it:

The first animation pencil test was often of every fourth or fifth drawing, exposed for a number of frames equal to the number of skipped drawings. This saved camera time and Bill felt the jerky projected tests still gave him the feel of the timing. If he thought the action was a little off, he’d rework the same roughs, so he wasn’t wasting much away. All testing was from rough drawings. Bill could do 200 or 300 feet a week, of single characters, but slowed down with Oswald Rabbit because he always had trouble drawing him.

This last sentence showed how in some ways there was trouble brewing. Oswald was the star character and Nolan lacked affinity for him. However, over time, this allowed Moreno to grow as a specialist. He was not only capably animating Oswald but also seemed to understand the direction in which the design needed to move to keep up with rapid advances by artists at Disney.

The 1930s were years of quiet ascendence for Moreno. Walter Lantz reassigned him back to his unit and gave him supervisory duties and then ultimately made him the de facto director of mid-30s Universal films. Moreno’s influence and leverage over the animated productions were considerable, yet his film credits (even frequently as the top-billed animator) did not sufficiently impart to moviegoers the outsized role he had taken on at the studio.

Meanwhile, the stature that Nolan first enjoyed began to cool. His character animation didn’t develop further. It could be a bit self-indulgent and show-stopping and eccentric. The arrangement he had with Lantz also became strained when the budgets tightened at Universal. Eventually, when his contract expired, his salary was seen as excessive and he was not renewed. That’s when other animators looked to Moreno as the foreman.

Meanwhile, the stature that Nolan first enjoyed began to cool. His character animation didn’t develop further. It could be a bit self-indulgent and show-stopping and eccentric. The arrangement he had with Lantz also became strained when the budgets tightened at Universal. Eventually, when his contract expired, his salary was seen as excessive and he was not renewed. That’s when other animators looked to Moreno as the foreman.

Working on Oswald, he learned Nolan’s artistic and technical approaches to animation. In a way, he inherited the mantle from him (Tex Avery did, too, for a while), though I’d guess Manuel was a better delegator and manager, whereas Bill was famed for his singular output. They both, in their respective periods of influence, held sway over the shop floor with creative authority and mechanical knowledge, while Lantz continued to hold the reins as the business producer (and film editor).

Bill Nolan deserves the recognition that this long-ago interview now reveals. The open secret among the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit animators has slipped into secrecy once again: it was Nolan who wrote and drew How To Make Animated Cartoons, the last lesson of the W.L. Evans course. During the era of silent cinema, when information was scarce, this was a valuable guide for aspiring animators like Moreno and likely Walt Disney. The first generation of Hollywood animators had just scraps of information to consult, yet they innovated and brought animation into a new era of artful performance.

Special thanks and acknowledgements to Mario Prietto, Devon Baxter, and John Garvin for images used above. The family and descendants of Manuel Mario Moreno have been incredibly generous in helping me with my research, which is taking shape now as a book. The Manuel Moreno Papers, a collection of his documents and materials, reside at Stanford University.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Another great historical post. Thanks Tom.

2 gems of animators, unearthed. Good reads.

I wish someone would do a deep dive into Nolan’s time with Otto Messmer. I suspect that Nolan’s system of circles had a major impact on the Felix cartoons.

If Bill Nolan had lived as long as Grim Natwick, he would no doubt have been interviewed later in life by Milt Gray and Michael Barrier, if not others, and at that point he would have been able to discuss his work on the W. L. Evans correspondence course in some detail. But he didn’t, which makes this account of Moreno’s all the more valuable. Thanks for posting this, and please keep us updated on your forthcoming book on Moreno. I’m sure it will shed new light on the early history of animation.

I remember he drawn Oswald from the late 1920s.

Historically a very important pair of posts! Thank you, Mr. Klein, for such a revelation.

“… the budgets tightened at Universal.”

Perhaps many of you may know that Universal went broke in the mid-1930s during the Great Depression (as did Paramount; and Fox Film Corp. almost did). Universal Studios founder and studio head Carl Laemmle had to give up the studio to the “suits,” his creditors. Hence the tightened budgets. That’s also the reason that very few Universal cartoons of the 1930s are in color.

Bill was more than just circles. They have so much weight and 3D-ness. He was a master, on a par with…TYTLA!