A 1963 New York Times movie review opined that “Kirk Douglas might do better sticking to Westerns and rallying Roman slaves than to try to bull his way through the fragile crockery of Cary Grant-type comedy.” The reviewer directed this zinger at Universal’s For Love or Money, a lightweight farce in which Douglas wears tailored suits, delivers bon mots, and is surrounded by three gorgeous women the whole time, including a pre-Catwoman Julie Newmar already appearing in athletic tights.

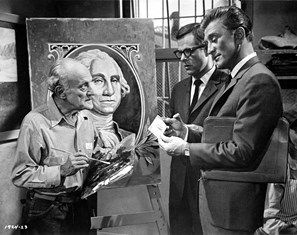

Yet, amazingly, when Kirk Douglas quipped during shooting that he “never played second fiddle before,” he wasn’t even referring to his curvy co-stars. He was talking about the set paintings of Edgar O. Kiechle, an artist who first came up through the studio working on backgrounds for Walter Lantz. In fact, in the late 1930s when Universal cartoons were finally filmed in three-strip Technicolor, it was Kieche who delivered those vibrant brushstrokes that often stole the show from the cel-painted characters in front. Perhaps this gave him some early practice on how to upstage a star.

He was enormously prolific during the feverish production schedules of the late 30s when Lantz was turning over every stone to find a leading player to replace the faded Oswald Rabbit. As I mentioned in my earlier post, Kiechle played a significant role in working with directors like Alex Lovy and Burt Gillett to visualize this turnstile of arriving and departing characters. This desperation to experiment and innovate led to enormous leaps even within the timeframe of character development.

Andy Panda emerged as a moderate success, so there were efforts to juice his appeal. He started as a baby, then was aged up, and then became more of a contemporary kid before he reached rapid adulthood. In his debut, Life Begins For Andy Panda (1939), he appeared in a strangely exotic tropical locale. He was subsequently made to deal with adversarial pygmies, despite the fact that it was well known in the 30s that panda bears were from China.

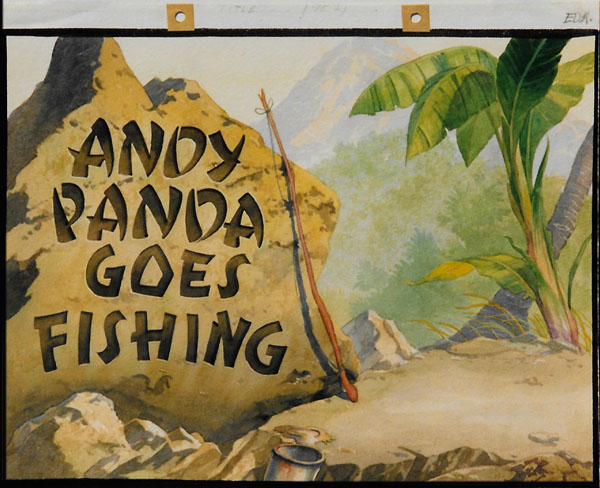

There is no worse example of the disjointed mélange of studio panic than Andy Panda Goes Fishing (1940). This features an oddball collection of fishing gags playing out while the pygmies encircle Andy because they have seen a warrant from the Chicago Zoo to capture a panda. An electric eel is hooked and wreaks havoc all around, including a number of flashing advertising gags. At least Kiechle had some interesting work with the tropical exteriors, but Andy—thank God—grew up in a hurry and left this short-lived and groundless series of unfortunate shorts co-starring Mr. Whippletree the turtle.

Ed Kiechle also wanted to grow up fast. His tenure in the Cartoon Dept. was a promotional launchpad over to his preferred work on the features. By 1942, he was formally assigned to the Art Dept. and worked as a sketch artist and set designer, but not before helping to commence the Golden Age of Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Although his next twenty years in the industry would have him working at other studios too, it was Universal where he most consistently worked. He regarded Universal City as his home base, remaining there long after Lantz had moved the animators off the lot.

He had engineered this career switch by spending his lunch breaks on sets, sketching in front of directors. Now that he was working in the Art Dept. he drew the attention of the stars themselves. After Ida Lupino commissioned him to do a portrait of her sister, the word was out. Helmut Dantine bought an oil painting for a friend. Jerome Kern and Ira Gershwin each bought a few. Soon Hedy Lamarr, Georgie Hale, and Preston Sturges all had a Kiechle hanging in their homes.

By the 1950s, his reputation had spread wide. He was critically acclaimed as a regional artist, his work appeared in galleries, and Universal had built a large enough collection of his oils that the studio began to rent his work to appear in any number of Hollywood movies, including Imitation of Life (1959), Portrait in Black (1960) and Lover Come Back (1961). Kiechle also provided the set sketches for such Hollywood classics as The Quiet Man (1952), An Affair to Remember (1957) and Spartacus (1960), the erstwhile masculine epic that the Times reviewer thought Kirk Douglas should “stick to.”

By the 1950s, his reputation had spread wide. He was critically acclaimed as a regional artist, his work appeared in galleries, and Universal had built a large enough collection of his oils that the studio began to rent his work to appear in any number of Hollywood movies, including Imitation of Life (1959), Portrait in Black (1960) and Lover Come Back (1961). Kiechle also provided the set sketches for such Hollywood classics as The Quiet Man (1952), An Affair to Remember (1957) and Spartacus (1960), the erstwhile masculine epic that the Times reviewer thought Kirk Douglas should “stick to.”

When director Michael Gordon and set decorator Ruby Levitt scored a hit with Pillow Talk (1959) for Universal, they struck on the superstition that the Kiechle set paintings were a lucky charm, so he thereafter made conspicuous use of them in subsequent films. When he directed For Love or Money, one aspect of the script was ideal for this purpose. One of the three women—each of whom is a wealthy heiress—is a bohemian who spends her money on an art gallery. Gordon must have salivated at the prospect of having such a good reason to fill his set with Kiechles.

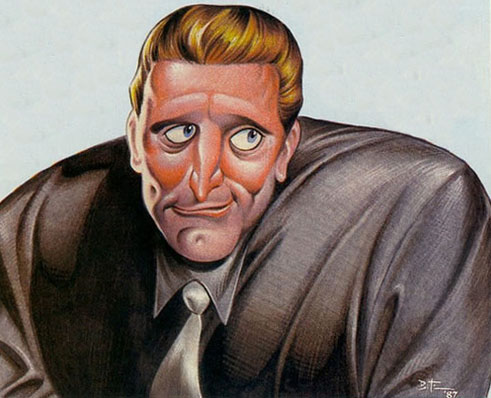

Judging from the 1963 publicity photos in which he is surrounded by modern art, Mr. “I Am Spartacus” stood there like a chiseled statue, handsome and manly, perfectly fitted by Costume and Wardrobe. His cleft chin was no less pronounced among fine tailoring than it was thrusting out of a helmet. Legend has it that when they hung a framed Kiechle over his shoulder, to dress the wall behind him, he joked to the crew, “I never played second fiddle to a painting before.”

Special thanks to Paula Kerris and Joe Carroll. The illustrations shown here are from the Kiechle family estate, photographed from the original courtesy of Paula Kerris, the daughter of Edgar O. Kiechle. The caricature of Kirk Douglas is by John Kricfalusi and Bruce Timm, both of whom cast their own big shadows over modern cartoons much like that famous granite chin that inspires their drawings. John K. regards Kirk Douglas as his favorite actor and a great hero of cinema.

I should mention that this story above, like any anecdote over time, is paraphrased and may have different versions, but this is how it’s been told among the Kiechle/Kerris family. There is a post about the 1940 MGM Matte Dept. that includes a staff photo with Ed’s father, Otto Anton Kiechle. On that site, the quip by Kirk Douglas—when the Ed Kiechle painting is raised over him—is different: “I’ve worked with a lot of tough directors, but he’s the first one who ever insisted on holding something over an actor’s head.”

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Another cartoon connection to For Love or Money is co-writer Larry Markes, who composed scripts for The Flintstones and The Jetsons, as well as other Hanna-Barbera productions.