Ed Kiechle, at Universal, circa 1938

The Lantz studio provided many artists the opportunity to develop their expertise, even if they might later have done their most notable work elsewhere. In the case of painter Ed Kiechle, he played a role in the introduction of Woody Woodpecker yet his contribution at Lantz has been largely overlooked.

The biggest reason for this is that he did not receive screen credit, even though he was the studio’s background artist for a significant period, from late 1935 until 1941. He arrived at an interesting time, just as the stylistic influence of Disney caused sweeping changes to the Universal cartoons.

Oswald the Rabbit was given a cuter design with white fur, in keeping with the growing cuteness of Disney characters, and Kiechle was instrumental in establishing a lush new painterly approach. The stylistic transition from 1935 to 1936 was quite pronounced, owing much to Kiechle’s talent and prodigious output.

He was the only background artist for the entire slate of Universal cartoons at that time, though he usually had one assistant. To keep up, he maintained a practice of speed-painting, even boasting that he could paint a tree in 15 seconds. Despite his breakneck pace, his work accounts for the most lavish background art at Lantz for any stretch.

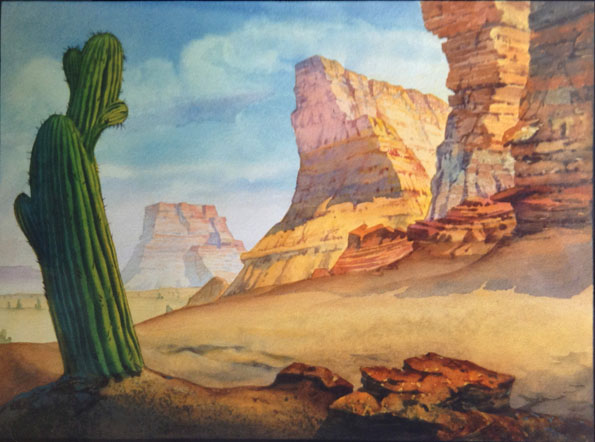

His early work at the studio was restrained, filmed in black-and-white, but a look at a Technicolor example from Syncopated Sioux in 1940 is to marvel at his control of bold washes of watercolor to create an American West landscape framed by looming rocky buttes and a foreground cactus, below. Such epic backgrounds can surely upstage the animation playing in front.

Background by Kiechle for “Synchopated Sioux” (1940)

He was born Edgar Otto Kiechle to a father who first painted stain glass windows and then Hollywood film backdrops when he moved the family to Los Angeles in 1919. Kiechle went to Fairfax High School, coincidentally attending with Ed Benedict, and then studied drawing and painting at the Otis Art Institute. He was hired as a background artist with the Iwerks studio before arriving at Universal.

He made an immediate impact working with Manuel Moreno—directing on behalf of Walter Lantz—to develop the monkey series Meany Miny Moe. This series was problematic because it was too expensive, requiring animation for three main characters, so it never supplanted Oswald, but it allowed Kiechle to develop this richer stylization for the Universal cartoons.

His role on Meany Miny Moe, ending in 1937, heralded the efforts that he continued throughout the late-1930s. Universal was pressuring Lantz to find a star to replace Oswald, but that effort proved difficult, involving attempts to introduce numerous new characters and series. Kiechle could work in a range of styles, and he was adept at working with new directors to provide visual development, so his contributions were particularly valuable during this turbulent time.

Walter Lantz was rotating through directors and Ed collaborated with each of them. In 1939, he worked with Elmer Perkins to develop Charlie Cuckoo, a cartoon that seems now like a precursor to Woody Woodpecker. Not only is Charlie a crazy bird who leaves behind his cuckoo clock, but he even runs into a woodpecker before opting to return home. The sketches and designs for this film, below, are by Ed Kiechle.

Kiechle’s visual development for “Charlie Cuckoo”

(1939)

He developed these layouts and storyboard panels to assist directors like Burt Gillett and Alex Lovy, using pastels, oil crayons and watercolors to determine the look of their cartoons in pre-production. This shows the deep level of Ed’s involvement at this time, and it also suggests how prolific he was because he was still required to complete the background paintings for every cartoon in a full year’s slate of releases for several directors.

Even while he was working on the cartoons, he was walking around the Universal lot and sketching the movie sets on his breaks, daydreaming of working in the Art Department for the feature films. It might have been thrilling to develop new series, but perhaps it turned to frustration as the failures mounted. The short-lived cartoons are in some cases most remarkable for their backgrounds, such as Lovy’s Babyface Mouse series.

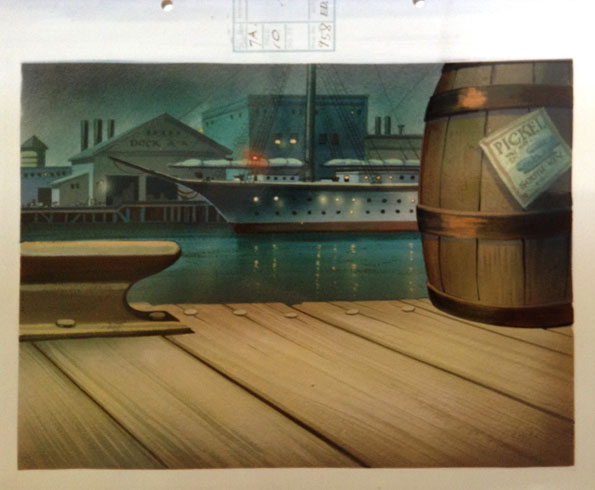

As a case in point, look at this atmospheric background from The Sailor Mouse (1938). In later years when Ed was also displaying his artwork in galleries, he was especially admired for his night scenes. This painting of a loading dock shows an early example of his penchant for nighttime lighting.

Background by Kiechle for “The Sailor Mouse” (1938)

Another thing that makes this background so special to show is that The Sailor Mouse is a black-and-white cartoon, so you’re seeing this painting made widely available in color for the first time. The production artwork remaining from these years shows that Kiechle was regularly painting in full color, owing to either his undaunted spirit or an understanding that Lantz was negotiating with the Technicolor corporation.

Ed lent his hand to all the attempts to find Universal’s new animated star. These include one-offs that were billed as Nertsery Rhymes and Cartunes, and also character-based episodes like Nellie the Sewing Machine Girl — with her knucklehead hero Dauntless Dan and villain Rudolf Ratbone – as well as Babyface, Li’l Eightball, and Punchy.

Finally the big break came in 1939 with Lantz seizing on the Panda-mania that swept America in the wake of bear cub Su Lin’s arrival at Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo. Kiechle must have been elated when Lantz was finally able to secure a license to release the cartoons in three-strip Technicolor, enabling him to showcase his talent to full effect.

The second Lantz cartoon filmed this way was Life Begins for Andy Panda. It was a genuine hit with exhibitors, and Kiechle’s beautiful art gave it the veneer of something brimming with Disney quality. However, there were enough issues with Andy as a character that they tried to recast him. It was in this context that Ed finally painted the big debut.

Knock Knock (1940)

In a short time, Andy went from an animal in an exotic jungle to a kid in a country cottage in Knock Knock (1940). When his Pop runs up to the rafters to deal with some contemptible pecking on the rooftop, there it was—a hole in the typically sublime Kiechle background. Woody made a star’s entrance, poking his head through and irreverently taunting, “Guess who?”

Woody Woodpecker was the bankable attraction that finally righted the fortunes of Lantz Productions, yet Ed Keichle switched jobs on the heels of that triumph. He got the position in set design he had long coveted, so his excursions across the Universal lot sketching in front of movie directors apparently did not go unnoticed.

However, what has gone unnoticed is his role as the primary background artist for Walter Lantz from 1935-1941, figuring in the introduction of Woody. It’s as if the woodpecker exploded into film history, launched from that little hole, but Ed could never slip through it himself to gain acclaim, except for his work outside of animation.

In all those years, Ed Kiechle never got an on-screen credit in the cartoons. I don’t know the reason for this, especially since his successors did, but it has led to an unfortunate oversight that exists to this day, propagated on the internet. Check the films on IMDB or Wikipedia or cartoon blogs with listed credits. Guess who’s not there?

I know that Walter Lantz held Ed in very high regard, even citing him as a person in his life from whom he learned the most about painting. Perhaps there was a contractual reason that Kiechle was absent from the screen credits of so many cartoons, but it is time that he we paint him back into the picture.

(Special thanks to Paula Kerris and Joe Carroll. The illustrations shown here are from the Kiechle family estate, photographed from the original artwork courtesy of Paula Kerris, the daughter of Ed Kiechle.)

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

This is beyond astounding. Sublime work, Tom!

Thanks for an informative overview of a truly unsung hero of the Lantz studio; you’re right, his paintings are marvelous!

That was great. Thank you. It’s always a pleasure to learn about a golden age artist that was unfamiliar.

Wasn’t Willie Pogany doing backgrounds for Lantz during at least part of the same period?

I think Leonard Maltin in “Of Mice and Magic” mentioned that Pogany did backgrounds for “Scrambled Eggs,” which featured the Peterkin character, and “Boy Meets Dog,” the Ipana Tooothpaste-sponsored cartoon with characters from the “Reg’lar Fellers” comic strip.

Willy Pogany was basically “one-and-done”– on contract for a single Lantz cartoon, “Scrambled Eggs” (1939) for which he did the BGs and created the character Peterkin. But I’m glad you mentioned: it’s because of Pogany that I stated above Kiechle was the “primary” (not “only”) BG artist from 1935-41, but Kiechle was effectively in charge and producing all backgrounds in that period. In fact, the case of Pogany makes Ed’s lack of screen credits seem more unfair. Ed K painted nearly every Lantz cartoon over 6 years without a credit, and Pogany was brought in for ONE cartoon and received screen credit. Of course, Willy Pogany was at that point already a very prominent illustrator so of course Universal wanted to showcase his name as a selling point, but it nonetheless does underscore the situation that Kiechle has become an invisible man in animation history, with Pogany’s work better known on his single outing than Kiechle’s for six years as a solid work-horse of the studio, including the classic “Knock Knock.”

Checking out one copy on YouTube, taken from one of Thunderbean’s DVD’s, the credit for backgrounds in “Boy Meets Dog” went to Chas. Conner and Roy Forkum.

The system was very unfair in those days when they chew you up and spat you out.

Did Ed Kiechle repaint the background for THE SAILOR MOUSE in grey tones for actual production, or did they shoot the color BG in black and white with B/W cel painted characters over it?

Take notice how the background pantings give plenty of room for characters to act over it without obstruction with plenty of details still visible. Fantastic BG painter, one who I have admired without knowing who he was until now.

‘Pat’

http://www.patcartoons.blogspot.com/

Pat, I agree the BGs are both fantastic as stand-alone art and practical in the sense that they serve the animation so well. Ed only ever painted one final background; there wouldn’t be a color and b&w version. I’ve seen a few cels from that period and they seem to be b&w, so it’s very likely that at some point the BGs were color with b&w cels over them, but just before Technicolor began at Lantz they likely were switching the entire production process to get the hang of it. It’d be fun to know which cartoons were “secretly” full-color and then shot to b&w film stock. I’ve never researched that.

I really liked to backgrounds in the mid-30s Walter Lantz cartoons. I remember one Oswald set in a dog and cat hospital, in which the backgrounds had rather grim items like cat skeletons in bell jars, painted in grayish tones so they didn’t really stand out but were visible if you were looking.

Here’s one I found a few weeks ago; there was no action over it, just a long pan across a bunch of angry-looking toys (from the Oswald “Puppet Show”). I assembled it from YouTube screen shots.

http://i695.photobucket.com/albums/vv319/ashbul/toys%20background_zpsucwlfk02.jpg

Look at this gorgeous background from the Lantz cartoon “Nellie of the Circus” (1939) :

https://comics.ha.com/itm/animation-art/painted-cel-background/nellie-of-the-circus-painted-pan-background-walter-lantz-1939-/a/7171-97431.s