EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first of a new series of columns that will appear here twice a month (on Saturdays) that will delve into the archives of Walter Lantz Productions. It is written by one of the true experts on the subject, Tom Klein. I met Tom years back, when he was cataloging the Walter Lantz archive at UCLA. He’s gone on to pen many scholarly articles on Lantz, was a consultant for Universal Cartoon Studios during the production of 1990s Woody Woodpecker series and served as the Director of Animation for Vivendi-Universal’s educational software division. He is currently Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Merrymount University in Los Angeles. We couldn’t be in better hands to learn more of the story behind Walter Lantz Productions. – Jerry Beck

Any Cartoon Researcher, after gathering enough history on a studio, starts to wonder what was it like to be there? The effect of all that random knowledge about a place, all those anecdotes and all its wild animation, is to get a sense about the everyday hustle and bustle of its moment-in-time, with the added goosebumps of knowing what was yet to come.

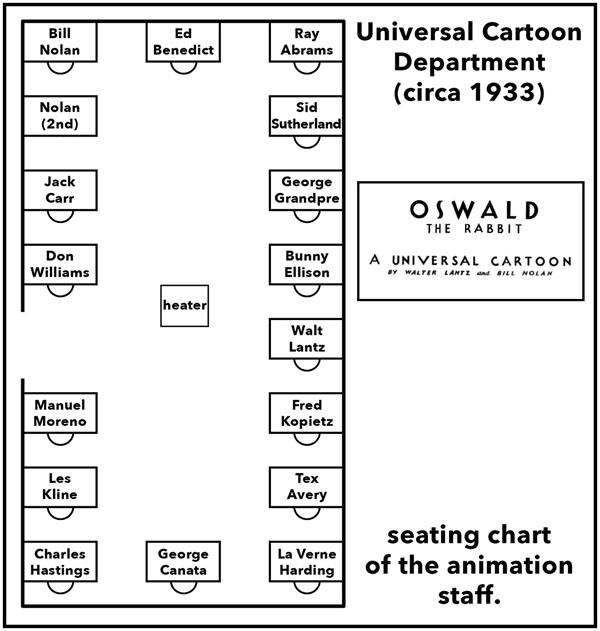

Just imagine being at the Universal Cartoon Department, as it was formally called, in 1933. It wasn’t yet the Walter Lantz studio, but it was edging closer to being that way. Lantz was the co-director with Bill Nolan of the post-Disney Oswald cartoons. He had a private office, but he still kept a desk in the animator’s bullpen, usually working alongside them in the race to meet deadlines.In the back corner were two young rising talents: Tex Avery and La Verne Harding. He was a boisterous Texan asserting himself as a creative force and she was quietly proving that women could draw just as well as men. Harding was the pioneering first female animator in Los Angeles; Avery was a natural gagman developing his signature style here, both on paper and as a ringleader of pranks.

To his left was Charles Hastings, the man who would soon shoot Tex in the eye with a paperclip, causing so much ocular trauma that his vision only worsened. By the time Avery parted ways in 1935, he was blind in his left eye. Some would say this forever changed his mood, driving him to be more ambitious and then in later years withdrawn, but in ’33 he was filled with youthful charisma. He was handsome, barrel-chested, and still had his hair.

Lantz’s hair was even thinner, and he was surely under a lot more stress than the outward appearance of this spirited animation room might belie. Universal was beset with cronyism and diminishing profits. In the 30s Universal Pictures would have collapsed had it not been for the success of its monster movies. The rest of its slate was underperforming, including the slowly down-trending Oswald cartoons.

Lantz had to keep re-negotiating the contract extensions for the series to continue. He did this by reducing costs each year. Additionally he was jostling against rivals, and to survive he became adept at the producer’s art, winning concessions and cutting backroom deals. Bill Nolan had been indispensible when he joined in 1929, but by 1933 there was tension: Nolan was too expensive to keep around.

Lantz had to keep re-negotiating the contract extensions for the series to continue. He did this by reducing costs each year. Additionally he was jostling against rivals, and to survive he became adept at the producer’s art, winning concessions and cutting backroom deals. Bill Nolan had been indispensible when he joined in 1929, but by 1933 there was tension: Nolan was too expensive to keep around.

He dealt with it through a kind of creative isolation. His animated sequences are bizarre, even by the standards of Oswald cartoons, and they often didn’t relate well to the flow of gags from the younger animators. Yet he remained a legend from New York for his prodigious output, though increasingly his work just looked like old-fashioned 1920s visual anarchy. He resisted adapting to the new method of planned animation that was becoming industry-standard.

Nolan drank only moderately and generally wore a gray sweatshirt to work. His biggest indulgence might have been that he had two desks, so that he could turn his chair and draw at a secondary workspace just behind him. Ed Benedict was his assistant, working next to him at the very front of the room.

Benedict was one of the earliest artists that Walt Disney hired, but in a regrettable decision this was the year he jumped ship to work for slightly more money with Lantz. Here he was cleaning Nolan’s eccentric sequences. He lit his cigarettes and soldiered on, with a growing awareness of what he had left behind to join Universal.

He had gotten some art training while at Disney–Walt would send the studio artists down to the Chouinard School for Friday evening classes–and Ed tried to spark some of that same fervor here. He and Fritz Willis set up life drawing sessions every Wednesday night and 10-15 people would show up. However, it wasn’t like the experience at Disney and in time it petered out. At Universal, there was no ambition from management for the artistry to get better.

He had gotten some art training while at Disney–Walt would send the studio artists down to the Chouinard School for Friday evening classes–and Ed tried to spark some of that same fervor here. He and Fritz Willis set up life drawing sessions every Wednesday night and 10-15 people would show up. However, it wasn’t like the experience at Disney and in time it petered out. At Universal, there was no ambition from management for the artistry to get better.

When I took a visit to Ed’s house in Carmel, California in March 1995, I was eager for the kind of details that would provide me more answers to what was it like there? And in pursuit of that, I asked him, “Where did everyone sit?” Ed at that time spoke in the slow labored breaths of a lifelong smoker. He was in his 80s and he was bemused by the question. I think he judged it not worth all that breath to scratch at such a trivial memory.

To me it wasn’t trivial; this was texture. Ed was surely a good sport in obliging me. He started sketching a room layout to see if he could remember. It was like a puzzle coming together, but eventually he had a working version of the desk arrangement from shortly after his arrival, a sixty-year reach back into his memory banks that’s been one of my personal treasures as a Lantz studio historian.

Over the last two decades, I have often looked at this seating chart to “see” how things might have played out there. It helps me understand how things spatially related and where exactly things happened in this main workroom of Universal animators.

For example, it even gives some insight into the blinding of Tex Avery in one eye. From the seating chart it is apparent that Hastings worked slightly behind him, across and to his left. That will be the topic of my next blog post, so I leave you simply with this cliff-hanger ending, moving forward a year, with Hastings pulling back that paperclip under tension of a rubber band, squaring up for a shot at Tex.

Look for these new entries at least twice a month about the studio managed by Walter Lantz, back to the days when the boys all called him Walt. Yes, the other Walt, in charge of that same Oswald.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Great stuff.

So, why did Charles Hastings shoot Tex Avery in the eye with a paper clip?

Answer 1: Just to watch him die.

Answer 2: He was starving, and Tex suddenly appeared to him as a giant roast chicken.

Mork: “Humor! Ar! Ar!”

Most likely, it was a prank gone wrong.

From Page 157 of Joe Adamson’s ‘Big Apple’ book “Tex Avery: King Of Cartoons”…… “While I was at Lantz’s in the early thirties, an incident occurred that made me feel the animation business owed me a living. We were all a group of crazy gagsters that would attempt anything for a laugh, and one routine was the rubber band and paper spitball shot at the back of the head. You’d pop a guy, hit him, and he’d yell “Bull’s-eye!” We had one goof there that had actually been kicked in the head by a horse! (Had a huge scar across his forehead.) He was really a bit off. He went a step further and used a wire paper clip. One of the boys yelled “Look out, Tex!” and I turned and caught the clip in my left eye. That lost me one eye in a split second.”

Let’s ask Hastings his side:

“Those were tough times at the Lantz shop. There was no heat. Nobody got paid. The place was filthy; there was film emulsion all over the floor that was sticky and would ruin your shoes.

“Women would avoid you – they’d notice the graphite under your fingernails and knew what you did for a living. That’s it, no second date. Lantz kept a pet monkey that he’d let free at night. You’d come in the next day and find your work had been ripped to shreds. Walt thought that was funny.

“I am bitter that I wasted my youth in that infernal pit. But there’s one thing I don’t regret, and that’s shooting out Tex Avery’s eye with a paper clip!”

“He went a step further and used a wire paper clip. One of the boys yelled “Look out, Tex!” and I turned and caught the clip in my left eye. That lost me one eye in a split second.”

God that must’ve been a terrible situation to be in.

As Artie Johnson usually put it- “Verrrry interesting!”

I’m really excited to see you posting here, Tom. Long-time admirer of your work profiling the history of this neglected, underrated studio.

Here’s to a Mutual Admiration fist-bump, Thad! I’m a big fan of your Paramount posts and your Thad blog. Looking forward to sharing more good stuff from my personal trove of Lantz anecdotes.

Hello Tom, Excellent post that I will eagerly anticipate reading more in the future. We met back in the late 90’s at Universal where I was developing the Woody Woodpecker Show and had a few memorable conversations on Walter Lantz and his cartoons, always among my lifetime favorites and still are. Hope you remember.

Glad to see you posting here.

‘Pat’ Ventura

Pat, soo-ooo great to hear from you. I have such great memories of that show and I’m always in awe of your talent. Of course I haven’t forgotten you. I think we had a few lunches with Mark Kausler back then (and one with Bob J?) and I remember that over lunch we pretty well hatched a plan with the Uni Oswald reference-videos that I’d gotten a hold of there. We were rebel freedom fighters raisin’ the flag for Cartoon History. Great to get this message from you, cheers!!

Very nice Tom…and good to see your fine research work here. So wish Universal would recognize your expertise and pay you to produce more historical Lantz DVD volumes (Universal???….pay you!!! It is to laugh…)

This is regarding the Charles Hastings quote from Peter Mork. Where does this come from, Peter? It just doesn’t seem human that someone would be actually “proud” that they shot a fellow animator’s eye out with a paper clip. It’s hard to believe that this is really Hastings talking, and if it IS, I’m glad I never met him.

I believe those quotes are tongue-in-cheek. A gag, son, gag that is.

Oh, A gag from Mork! For little while I thought Thad was saying that Hastings was joking when he said that. At any rate, that bit with Lantz’s monkey is funny in a sadistic sort of way. Just be careful now that future internet “biographers’ don’t dig up that joke quote and attribute it as something Hastings actually said.

In light of that though, I’d still like a future article entirely devoted to stories/anecdotes about Walter Lantz being a dick.

Did I make it all up? Maybe. I think of it more as enhanced postulation – things which, if not strictly factual, greatly add to our appreciation of a history we cannot ever really understand, at this temporal remove.

Well here’s a little tale of Walter Lantz being inhospitable anyway…I ran the projector for the Annie Awards Banquet in 1973, for the second annual presentation at the Sportsmen’s Lodge. Walter was the only recipient that year, and I put together the film presentation from prints he loaned to ASIFA and some clips of Walter that I had. When I went to the old Lantz studio over on Seward the next day, to return the prints, I was happily anticipating having a few words with the man himself. After waiting in the foyer for awhile, Walter Lantz came through a door in the back of the studio and took the films from my trembling hands. Before I could say anything, Walter declaimed; “Aw, let the old man get back to his spaghetti, will ya!?” He tuned on his heel and walked back through the door, slamming it. I stood there in shocked silence, feeling my chance for fannish encounter gone forever. I probably interrupted his lunch!

I remember you told this story before in one of The Animation Guild’s interview podcasts some years back. I suppose I would’ve felt that way as well if I was so close to get to talk to someone who inspired me to be an animator at all. I recall you also said you tried to get a job there as well before it closed and was told you had to wait until these guys died first!

Having gathered quite a bit of anecdotal history on his studio, I can say that the overwhelming impression Walter made on his contemporaries was favorable to great. Like any man, he was not without his foibles– that’s only human — but he endured those toughest professional years in the 1930s with his dignity intact and he came out a big winner with a star in Woody and a small studio to call his own. That’s really quite admirable and amazing. And, along the way, he registered a few milestones of forward-thinking without making a fuss about it: the first animation producer to offer a 5-day workweek, and in Hollywood he promoted La Verne as the 1st woman animator (mentioned above) and then Manuel Moreno worked as the first Mexican-American director (more on that in future posts). I’ll be sure to never sugarcoat a story, and there’s some crazy ones, but on his merits Walter was a stand-up guy.