John Foster circa 1917

John Foster Jr. was born in New Jersey on Nov 27th, 1886 to John and Louisa Foster, German immigrants who’d settled in Hoboken. He was the second oldest of six siblings. Foster quit school after 7th grade, sometime around 1900.

It’s hard to track Foster’s activity between 1900 and 1915, and I’m not aware of him working professionally as a cartoonist or illustrator during this time. By 1910, Foster’s parents were out of the picture and the six Foster siblings were sharing an apartment in Hoboken City. Dick Huemer recalled that Foster spent his early years working in the upholstery business, and on the 1910 census he is listed as a “Designer” in a “Shirt House”. This information seems to echo Mannie Davis’ recollection that Foster was a “homemade artist”. Davis recalled in 1970:

“He never studied, he just had a natural knack with comedy. And it was very funny at times, and he could draw enough to put it over. He couldn’t sit down to make an ink drawing, but he adapted himself to animation. He was considered very funny in the early days, inventive with his ideas.”

Foster seems to have begun his animation career around 1916 at the first Mutt and Jeff studio, based in Fordham and at the time managed by Raoul Barre and Charlie Bowers. Here Foster was active both in the story and animation departments until enlisting in the US Military on December 9th, 1917. A 1940 publicity newspaper on Terrytoons profiled Foster and others, giving the following account of Foster’s beginnings in the animation business:

“John Foster’s experience, like Paul Terry’s, covers most of the history of the development of the screen cartoon. As a youngster with only amateur art experience, he answered a want ad for “pen and ink artists”, and was already working for Raoul Barre’s cartoon unit at the Edison company studio when the war interrupted his progress in the new field. Going to France with the 306th Field Artillery of the 77th Division, Foster went through eight months of action at the front , including the battle of Argonne. Immediately on his return to civil life he went back to animated cartoon work with the Hearst outfit, and in 1924 joined Terry in making Aesop’s Fables for Van Beuren.”

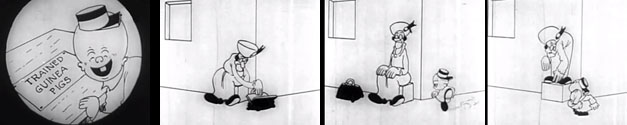

Foster was discharged on May 10th, 1919, and soon took a job with Hearsts’ International Film Service. Here he animated and gagged cartoons starring Hearst comic characters like “Jerry on the Job” and “The Shenanigan Kids”. Like his IFS coworkers Grim Natwick and George Stallings, I believe Foster’s animation style was greatly influenced by Bill Nolan during this period. Foster’s stylistic hallmarks can already be seen in his early animation here, such as drawing characters with one tooth, having them spin in place when reacting or entering a scene, and having them slide across the floor without animating feet movement. In later years, these animation “licks” were sometimes appropriated by Foster’s coworkers at Fables studios.

Foster animation in “Pigs in Clover” (1919)

In 1921, Foster married Charlie Bowers’ secretary Grace Ashton, who also dabbled in making exposure sheets for Bowers’ Mutt and Jeff cartoons. Ashton changed her last name to Foster, and they later had two children, John (B.1922) and Doris (B. 1924). Izzy Klein recalled in a “Cartoonist Profiles” article:

“ The other person in that office was Grace Ashton, a tall blonde young woman. (She became Mrs. John Foster, one of the early animation pioneers.) One of Grace’s chores was making out exposure sheets.”

“In those early days of animation, to save time for the animator at this studio, someone was assigned to make out the exposure sheets for each cartoon after it was animated. Bowers gave Grace Ashton this job. She was supposed to riffle the scene through her fingers to get an idea of the action and then mark down the exposure numbers. She sat in her office, often chattering with a friend as she did her work. Animators often grumbled that their animation wasn’t receiving the proper attention. But that was the system and you had to abide by it.”

John Foster settled at Paul Terry’s Aesops’ Film Fables studio around 1923, working as both an animator and the studio’s key story man. Around 1926, the studio’s production system was reorganized so that Terry’s 5 key animators would write and animate their cartoons almost entirely themselves. While Frank Moser, Jerry Shields, and Mannie Davis had no trouble animating an entire cartoon themselves on many occasions, John Foster and Harry Bailey tended to rely more heavily on the several other animators in the “Fables” bullpen to fill out their cartoons. On June 5th, 1929, Paul Terry declined to sign a new contract offered by Van Beuren and RKO that no longer granted him the publicity and percentage of ownership he’d previously enjoyed as studio director. Terry was forced to sell his share in the studio, and Van Beuren quickly gave Foster Terry’s job and contract.

Foster scene in “A Jealous Fisherman” (1924)

A common practice in the New York animation business was to give the studio director top billing in each cartoon’s credits, regardless of their personal contribution to the film. Fables Studios was no exception, and after November 1927 the films were credited plainly as “By Paul Terry and” whichever animator was the de-facto director. When Foster assumed Terry’s position as studio head in June 1929, his name replaced Terry’s as the first credit on each and every cartoon produced by the studio over roughly the next four years. Mannie Davis and Harry Bailey were chosen as Foster’s initial two directors, therefore a cartoon credited “By John Foster and Mannie Davis” is actually de-facto directed by Davis. Foster’s creative role during this time would’ve mostly been reserved to story work and working with the musical director, although he also contributed animation to a fair amount of the cartoons. The cartoons Foster produced at Van Beuren between 1929 and 1933 are a fantastic example of what the “Fables” group of cartoonists

could achieve when taken away from Terry’s tight fisted production style and left to their own devices.

The Van Beuren cartoons produced by Foster and his peers were not widely appreciated at the time of their release, and RKO executives were displeased with Van Beuren, who put the blame on Foster. According to Mannie Davis, “Bunny” Brown, a nephew of a top RKO shareholder, was appointed business manager of the studio in 1933 and butted heads with Foster. It’s unknown exactly when Foster was fired, but his name disappears from the Van Beuren product after “Love’s Labor Won”, a March 1933 release. George Stallings was promoted to head of the animation department in his place.

In February 1934, Foster was announced as a hire at Frank Goldman’s troubled studio Audio Cinema, Inc. The Film Daily reported on Feb. 23rd, 1934:

“To accommodate increased activity in the trick photography and animation field, Audio Productions, Inc., has moved its production headquarters from the Bronx to the Fox studios on 56th St. John Foster, formerly in charge of animation and cartoon work for Van Beuren, is in charge of animation. Alex Gansell, formerly with Visugraphic Pictures and Ufa, also has been added to the staff. Another appointment is Edwin Ludig, for 14 years with David Belasco, as musical director.”

Foster’s stay at Audio seems to have been a short one. Foster joined the staff of Paul Terry’s Terrytoons sometime later in 1934, his animation first appearing in Jack’s Shack, a November 1934 release. His scenes at Terrytoons continue in the tradition of the eccentric rubber hose style he developed two decades earlier, and exemplify some pretty wild drawing and timing. His scenes in such cartoons as Five Puplets, Opera Night, and Alpine Yodeler feature similar character designs to those seen a few years earlier in the early sound cartoons Foster directed at Van Beuren.

BELOW: Foster scene in “Moans and Groans” (1935)

BELOW: Foster scene in “Ozzie Ostrich Comes to Town” (1937)

From 1937 to 1938, Foster is credited as “Director” of a handful of Terrytoons, among them the first color Terrytoon String Bean Jack and the first two Gandy Goose cartoons. Foster likely developed Gandy out of an earlier effeminate goose character seen in many early 30’s “Fables” cartoons. Around 1938, Foster was made the head of the Terrytoon story department, working in collaboration with about 3 to 4 other writers that included over time Tom Morrison, Don McKee, Al Stahl, Izzy Klein, and others. Klein claimed that Terry and Foster’s ideas tended to make up the lion’s share of each story around this time, as he recalled in a cartoonist profiles article on the Terrytoon story department:

“I soon became aware that the board parallel to the long table was the Foster acceptance board. The other board was rejection or possibly “maybe or if” board. John Foster would go to the main board and lift off a gag sequence onto the other board. Those shifted sequences were never his gags. Terry would come into the room once in a while with gag sketches on small note paper and pin them on to the board. I call them sketches, though they looked more like bird feet marking on sand. Foster never moved them to the secondary board.”

“On Monday of the second week of the story, the director assigned to the picture joined the story crew and threw in his talent on the assignment. By the end of the second week the story was always finished. The final shape up of the story was made between Foster and Terry. All of Paul Terry’s gags were kept. Most of Foster’s remained and a sprinkling of the work of the other guys’ completed the opus.”

BELOW: Foster scene in “String Bean Jack” (1938)

Until recently, I was under the impression that Foster never animated again at Terrytoons after his 1938 directorial efforts. However, Milton Knight recently pointed out to me that Foster’s animation springs up again in several 1945 releases starting around June. In September 1944, there was a mass layoff of several Terrytoon animators, mostly due to the growing struggle between Terry and the Screen Cartoonists Guild. It’s possible that Terry briefly moved Foster back into the animation department to compensate for their departure.

Foster scene in “Mighty Mouse and the Wolf” (1945)

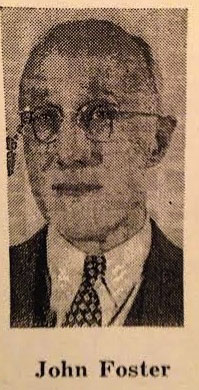

Sometime in the late 1940’s Foster began to develop Parkinson’s Disease, soon crippling one of his legs. He retired in 1949, his last credit appearing in Comic Book Land, a December 23rd 1949 release. In retirement, Foster was strapped for cash, and worked for Terry from home recording radio shows that Terry could recycle gags from. Foster’s son John, who some former employees recalled possibly had a mental disability, worked at Terrytoons as an office boy in the 1940s and 50s. John Foster passed away on February 16th, 1959.

John Foster – circa 1940

Unfortunately, Foster was never interviewed, and so his personality and unique sense of humor can only be interpreted through his cartoons. I always felt like Foster’s personal drawing style reflected the rubbery qualities of early German cartoonists like Wilhelm Busch, so possibly Foster’s German heritage contributed to his style. Paul Terry’s daughter Pat recalled Foster as more of a fun-loving type of guy:

“He was a character. I walked in to the story department one day, and he’s sitting there with what appears to be a nail sticking out of his head. He had taken rubber cement and stuck it to his forehead with a nail in it.”

Paul Terry himself thought very highly of Foster, later calling him the “best” and “most brilliant” of all his employees. However, like most of Paul Terry’s peers from the early days who stayed with him, Foster later became bitter and frustrated by Terry’s success and ego. Izzy Klein recalled:

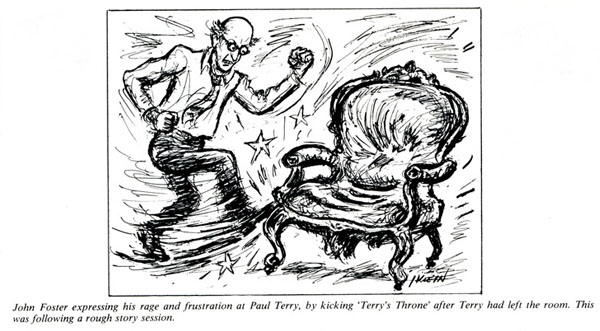

“When Terry remained (in the story department) for more than a walk through he would sit on an ancient wooden armchair with a leather seat stuffed with horsehair. The underside of the chair’s bottom was worn with age so that cloth and horse hair dangled from below. When Mr. Terry sat on this “throne”, filling it out completely and slightly sinking into the seat, with the ragged horsehair hanging underneath, the effect was most picturesque.

That armchair seemed so much to represent the boss. Once, after a very unpleasant session at which Terry ripped some of the sketches from the board (not his own), did some hollering and walked angrily from the room, John Foster went over to that throne and kicked it. He swore a blue streak as he swung his toe against the helpless chair. It was a sight to behold, this elderly gentleman going through such a foolish charade. The objective of all this furor was, as we all know, to make hilarious animated cartoons which would tickle the ribs of young and old.”

Special Thanks to Harvey Deneroff, Don M. Yowp, Milton Knight and Thad Komorowski.

Charlie Judkins is an animator and animation historian based in Brooklyn, NY. He also works as a Ragtime Pianist, and is the protege of Ragtime legend Terry Waldo.

Charlie Judkins is an animator and animation historian based in Brooklyn, NY. He also works as a Ragtime Pianist, and is the protege of Ragtime legend Terry Waldo.

love this series!

Outstanding post, Charlie! I’ve always wondered to what degree John Foster was responsible for the combo of eccentric animation technique and utter bizarreness so treasured in such Van Beuren “Don & Waffles” and “Tom & Jerry” cartoons as Gypped In Egypt and Piano Tooners.

Mac: “marvelous! simply marvelous” Tosh: “Indubitably!”

Very interesting. I wondered a few years ago whether “Van Boring” made a mistake when he fired John Foster, because I think those Tom and Jerry cartoons Foster made were pretty good – kooky and sort of “off center.”

Hah! Serendipity: A few years ago, I went through Graham Webb’s “Animated Film Encyclopedia” rather carefully, looking for cartoons about guinea pigs, and I found exactly TWO (out of 7,195 entries in that book) : A 1938 Columbia Krazy Kat cartoon entitled “Sad Little Guinea Pigs,” and a 1954 Disney cartoon called “Pigs is Pigs” (not to be confused with “Friz” Freleng’s 1937 cartoon of the same name). Now I know of three!

Incidentally, Graham Webb’s book also identifies the above 1938 color cartoon that Foster worked on as “_Stringbean_ Jack,” as the film clip indicates, not “Beanstalk Jack” as the text shows. (That was an earlier 1933 Terry cartoon, as well as a later 1946 one.)

Jim, you are correct about the title STRING BEAN JACK and I have corrected it in the post above.

Jim, you happen to catch this past Sunday’s “Simpsons” episode? Possible number four?

What a lovely article about my Grand Uncle John. Thank you!!

Uncle John’s daughter, Doris, was my Godmother. I have an album full of his personal illustrated

letter-cartoons (from 1937 & ’38) that he wrote to both Doris (Aunt Dorie) and John, Jr. (Uncle Jack), while he was working in New York and they summered on Fire Island with my Grand Aunt Grace (Auntie Dot), my Grandmother Marie Ashton, and my mother when she was a child. It brings me great joy to read your words about my Uncle’s talent and perseverance. I look at a photo of him, Dot, Dorie and Jack every day when I play the piano.

I always enjoy visiting this web site and especially love re-reading Charlie Judkins’ articles on early NY Animators, particularly that about my Grand Uncle John Foster. Fine and interesting reading!

Van Beuren definitely dropped the ball when he fired Foster. Without him, the Aesop’s Fables shorts and ESPECIALLY the Tom & Jerry shorts weren’t as good.