In this post, I will take a closer look at Tōei Dōga’s first three anime features. All of them received an Amercian release despite the fact they were each based on Asian folk tales – and were as far from Disney, aesthetically, as one could get.

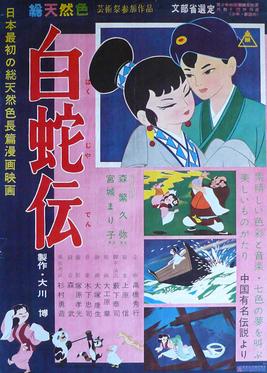

Tōei Dōga’s first feature was Hakuja-Den, a.k.a The Tale of the White Serpent, a.k.a The White Snake Enchantress, a.k.a. (in the U.S.) Panda and The Magic Serpent; directed by Taiji Yabushita (1903-1986) and Kazuhiko Okabe, and produced by Hiroshi Ôkawa.

The Chinese story was first written down during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.), based on a much older oral folk tale. The story as adapted by Toei is that, once in ancient China, there was a young boy, Xu-Xian (pronounced Shu-Shian), who had a pet little white snake. His parents made him turn it loose. Years later, Xu-Xian grew up to become a handsome young man with two loyal cute animal friends, a red panda (Mimi) and a small giant panda (Panda), but he never forgot the white snake. Meanwhile the snake, who was really a powerful animal spirit that had fallen in love with him, is turned into the beautiful Princess Ba-Niang. (As a princess, her fish-spirit friend, Xiau-Qing, becomes her human handmaiden, played for comic relief as a giggly teenager.) However Fa-Hai, an officious priest (Buddhist in some versions, Taoist in others; the American version just calls him the Magic Wizard) can tell that Ba-Niang is a supernatural spirit, and he assumes that she is an evil vampire preying on Xu-Xian. Since Xu-Xian refuses to give her up, Fa-Hai has him sent to slave labor “for his own good” to separate him from Ba-Niang. This also separates him from Mimi and Panda, who set out to find him and have their own adventure with the White Pig mob, a gang of dockside animal criminals. After lots of action involving escapes, reuniting, and magical battles, Xu-Xian is killed. Ba-Niang offers to the Dragon God to give up her immortality and her supernatural powers if he will restore Xu-Xian to life. This sacrifice convinces Fa-Hai that her love for Xu-Xian is genuine, and he blesses them to live happily ever after.

The Chinese story was first written down during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.), based on a much older oral folk tale. The story as adapted by Toei is that, once in ancient China, there was a young boy, Xu-Xian (pronounced Shu-Shian), who had a pet little white snake. His parents made him turn it loose. Years later, Xu-Xian grew up to become a handsome young man with two loyal cute animal friends, a red panda (Mimi) and a small giant panda (Panda), but he never forgot the white snake. Meanwhile the snake, who was really a powerful animal spirit that had fallen in love with him, is turned into the beautiful Princess Ba-Niang. (As a princess, her fish-spirit friend, Xiau-Qing, becomes her human handmaiden, played for comic relief as a giggly teenager.) However Fa-Hai, an officious priest (Buddhist in some versions, Taoist in others; the American version just calls him the Magic Wizard) can tell that Ba-Niang is a supernatural spirit, and he assumes that she is an evil vampire preying on Xu-Xian. Since Xu-Xian refuses to give her up, Fa-Hai has him sent to slave labor “for his own good” to separate him from Ba-Niang. This also separates him from Mimi and Panda, who set out to find him and have their own adventure with the White Pig mob, a gang of dockside animal criminals. After lots of action involving escapes, reuniting, and magical battles, Xu-Xian is killed. Ba-Niang offers to the Dragon God to give up her immortality and her supernatural powers if he will restore Xu-Xian to life. This sacrifice convinces Fa-Hai that her love for Xu-Xian is genuine, and he blesses them to live happily ever after.

In the original, much more complicated Chinese folk-tale, Xu-Xian is called Li Fong and he has two supernatural snakes who both become his wives. This was Americanized into an “original” science-fantasy novel, The Devil Wives of Li Fong, by E. Hoffmann Price (Ballantine/del Rey Books, December 1979, 217 pages), if anyone wants to read a smooth English-language version of the whole folk-tale. Without cute animals.

Hakuja-Den was Japan’s first color feature (76 minutes*), and was publicized as Japan’s first animated feature since everyone wanted to forget about Momotaro: Umi no Shinpei. All of the key animation of the main characters was done by just two animators; Akira Daikubara (1917-2012) for most of the humans (especially their fight scenes) and Yasuji Mori for the more “delicate” Xu-Xian and the cute animals. Production was from March to October 1958. Several later-famous Japanese animators including Rintaro and Yasuo Ōtsuka got their start on Hakuja-Den. It was released on October 22, 1958. Tōei (not Tōei Dōga) promoted it internationally. It was mentioned favorably at the Venice (Italy) Film Festival in 1959; if the Festival had a children’s film award, Hakuja-Den would have won it. It made some foreign sales, but none at the time to America. Here is an excerpt:

* running time information is for the American releases, which are usually cut down. The original Japanese releases are longer; considerably in some cases.

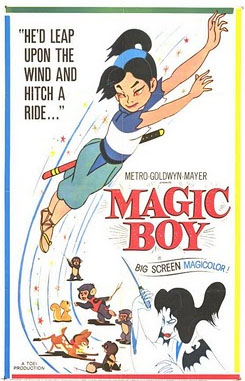

Tōei Dōga’s second feature was Shônen Sarutobi Sasuke, (later known in the US as Magic Boy) based on the medieval Japanese belief that ninja possessed magic fighting skills. The animation studio wrote an original story by Kazuo Dan and Dohei Muramatsu, but Sasuke Sarutobi was a popular fictional boy master ninja in novels and movies since the 1910s.

Tōei Dōga’s second feature was Shônen Sarutobi Sasuke, (later known in the US as Magic Boy) based on the medieval Japanese belief that ninja possessed magic fighting skills. The animation studio wrote an original story by Kazuo Dan and Dohei Muramatsu, but Sasuke Sarutobi was a popular fictional boy master ninja in novels and movies since the 1910s.

In the movie, Sasuke (10 or 11 years old) and his Older Sister (called just “Sasuke’s sister” in the American dub) are peasants living in the forest, where they have several cute animal friends: Koro the bear, Kiki the monkey (Cherry in the American dub), Ricky (Tinkle) the fawn, and others. One day an eagle seizes Ricky but drops her into a lake. Sasuke and the mother deer try to rescue her, but they are attacked by a huge salamander who kills the mother deer. After defeating them, the salamander turns into the evil witch Yakusha. Sasuke’s sister tells him that Yakusha has just escaped from a punishment spell by a good wizard a thousand years ago, and she now plans to use her own magic to conquer Japan. Sasuke ventures into the mountains to become the student of Master Tozawa Hakuun, a powerful magician-hermit, to fight Yakusha. After three years, Sasuke, now a master magician, returns to find that Yakusha and Gonkuro, her bandit-king henchman and his gang, have robbed and burnt the local village and kidnapped his sister. The rest of the movie is about Sasuke and Yukimura Sanada, a handsome samurai who has promised to help the villagers, fighting Yakusha and Gonkuro. A subplot develops a growing romance between Yukimura and Sasuke’s sister.

Shônen Sarutobi Sasuke, 83 minutes*, directed by Akira Daikubara and Taiji Yabushita, and released on December 25, 1959, was Tōei Dōga’s and Japan’s first animated film in Cinemascope®. It was considered both more “national” with an obviously Japanese story and setting, and more “modern” with a contemporary cartoon art style instead of one emphasizing a traditional Chinese look. It was faster-paced, with lots of battles. Despite being made to be more “saleable” to the American market, outside of being sold to MGM, it also did not make any American sales at the time.

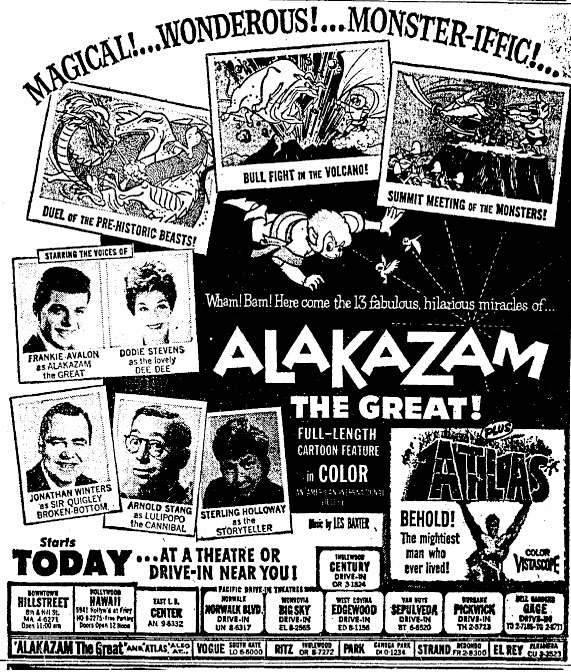

Saiyūki, Tōei Dōga’s third cartoon feature (88 minutes), was again an ancient Chinese folk-tale, but one that was extremely beloved in both China and Japan, and was much more humorous. What’s more, it was based on a very popular comic-book version by Osamu Tezuka, Boku no Son Goku (My Son Goku), published from February 1952 to March 1959. Tezuka’s version was full of modern anachronisms and “breaking the fourth wall” incidents of the characters or Tezuka himself talking directly (usually making snide comments) to the reader, which was reflected in the movie’s impishness. One suspects that the conclusion of Tezuka’ comic-book serial after seven years in March 1959 had a lot to do with Tōei Dōga’s decision to make the folk-tale the subject of their 1960 feature.

Saiyūki, Tōei Dōga’s third cartoon feature (88 minutes), was again an ancient Chinese folk-tale, but one that was extremely beloved in both China and Japan, and was much more humorous. What’s more, it was based on a very popular comic-book version by Osamu Tezuka, Boku no Son Goku (My Son Goku), published from February 1952 to March 1959. Tezuka’s version was full of modern anachronisms and “breaking the fourth wall” incidents of the characters or Tezuka himself talking directly (usually making snide comments) to the reader, which was reflected in the movie’s impishness. One suspects that the conclusion of Tezuka’ comic-book serial after seven years in March 1959 had a lot to do with Tōei Dōga’s decision to make the folk-tale the subject of their 1960 feature.

For all its fantasy and ancientness, Saiyūki or The Journey to the West is one traditional Chinese folk-tale that can be traced to an actual event. In the early 7th century, a leading Buddhist monk, Xuanzang (ca. 602-664), grew dissatisfied with major discrepancies in the Buddhist scriptures circulating around China. He blamed the many transcriptions of Buddhist texts over the centuries, which were probably based on mistranslations of the original Indian teachings of the Buddha around the early B.C. 500s. He decided that the only way to guarantee the authentic teachings was to travel to India to get a set of them “from the source” and retranslate them. Xuanzang spent several years learning Indian and waiting for the troubled international times to calm down. (China was at war with the Eastern Göktürks, and Tang Emperor Taizong had declared it illegal to leave China.) Finally in 629, Xuanzong left the monastery at Chang’an, persuaded sympathetic Buddhist border guards to let him out of China, and set out on a 17-year journey to India and back.

He had many adventures with bandits and warlords, but he was often welcomed and helped by Buddhist priests and local rulers along the way. He became increasingly famous during his journey, and his return to China in 645 was a triumphal parade (he brought back 657 Sanskrit texts, seven statues of Buddha, and many other “souvenirs”) that led to a command audience with Emperor Taizong, who urged him to write his memoirs from the detailed notes that he kept. Xuanzong’s Great Tang Records on the Western Regions is considered today the only accurate record of the politics and social life of 7th-century western China, the Central Asian kingdoms including modern Afghanistan, northern India, and the Silk Road trade route. Emperor Taizong helped him establish a translation center at Chang’an, and he spent the rest of his life translating the Sanskrit texts that he brought back with him, personally and with many disciple translators.

Xuanzang’s epic journey became legendary throughout China in oral form. The Chinese being who they were, the story gained many mythological elements over the centuries; notably Xuanzang’s three supernatural bodyguards, a monkey-spirit, a pig-spirit, and a sand-demon spirit (Xuanzong spent several months crossing the Gobi desert), and a dragon who turned himself into Xuanzang’s white horse. As the story evolved, the animal spirits grew more important until by the time the folk-tale was fixed in writing in the mid-16th century, Saiyūki the Monkey King had become the real hero, with Xuanzang reduced to a comedy-relief supporting character.

Xuanzang’s epic journey became legendary throughout China in oral form. The Chinese being who they were, the story gained many mythological elements over the centuries; notably Xuanzang’s three supernatural bodyguards, a monkey-spirit, a pig-spirit, and a sand-demon spirit (Xuanzong spent several months crossing the Gobi desert), and a dragon who turned himself into Xuanzang’s white horse. As the story evolved, the animal spirits grew more important until by the time the folk-tale was fixed in writing in the mid-16th century, Saiyūki the Monkey King had become the real hero, with Xuanzang reduced to a comedy-relief supporting character.

The feature was directed by Daisaku Shirakawa, Taiji Yabushita, and officially Osamu Tezuka; although Tezuka has said that his connection with the movie was strictly for publicity purposes. The only time that he was ever at Tōei Dōga was when the studio brought him in for photos of him at the animation desks. It was his publicity visits to pose among the animators that inspired him to create his own animation studio, Mushi Production Co., Ltd., the next year. Tezuka and Mushi Pro later did his own animated TV version of “My Son Goku” as Goku no Daiboken (Goku’s Great Adventure), 39 episodes from January 7 to September 30, 1967, with completely original character designs.

The story can be confusing because each main character has a variety of names depending on which Chinese language you use, or Japanese, or Indian. The Monkey King can be Saiyūki or Son Goku or just plain Monkey or Goku. The pig demon can be Zhu Bajie or “Pigsy”. Xuanzang may be Sanzo Hoshi. And so on.

Saiyūki was faithful to the spirit of Tezuka’s humorous comic-book adventure, although Tōei Dōga modified his character designs considerably, and drastically cut down his seven-year story. The dragon who becomes Xuanzang’s horse was removed completely. The movie was released on August 14, 1960.

Suddenly the American theatrical distributors, who had been ignoring Tōei Dōga for the last three years, wanted to buy all three features. But each was licensed by a different American distributor. The mighty MGM got Shônen Sarutobi Sasuke. American International Pictures, a small company that was then about as big as it ever got, picked up Saiyūki. And Hakuja-Den went to Globe International (or Globe Pictures), a company that I would swear that nobody ever heard of, but IMDb lists 44 movies that it distributed or produced between 1911 and 1972.

MGM changed the title of Shônen Sarutobi Sasuke to Magic Boy, and called the handsome samurai “Prince Yukimura”, but otherwise left the movie alone. However, since ninja were then equated by Americans as medieval forerunners of the Yakusa – thieves and murderers (which they were), not as romantic Robin Hood-like “good guy” bandits – MGM claimed falsely in its publicity that the original Japanese title of Magic Boy was The Adventures of Little Samurai.

American International spent the most money on its version of Saiyūki, hiring Sterling Holloway as a narrator and such well-known actors and voice artists as Peter Fernandez as Saiyūki’s speaking voice and Frankie Avalon as his singing voice, and Dodie Stevens, Jonathan Winters, Arnold Stang, and E. G. Marshall. The characters were given funny names: Pigsy became Sir Quigley Brokenbottom (Jonathan Winters), the Bull demon became King Gruesome, two bandits became the McSnarl brothers, Herman and Vermin, a cute child demon became Philo Fester, and Buddha, the Chinese goddess of mercy Kuan Yin, and Xuanzang became King Amo, Queen Amas, and Prince Amat. Minor characters were given well-known Western names; an old wizard became Merlin the Magician, and a massive warrior became Hercules. (Saiyūki used the line, “Your name is Hercules? I’ll call you Jerk-ules!” decades before Disney did in its 1997 Hercules animated feature.) And Saiyūki became Alakazam the Great, which was Saiyūki’s new name.

American International spent the most money on its version of Saiyūki, hiring Sterling Holloway as a narrator and such well-known actors and voice artists as Peter Fernandez as Saiyūki’s speaking voice and Frankie Avalon as his singing voice, and Dodie Stevens, Jonathan Winters, Arnold Stang, and E. G. Marshall. The characters were given funny names: Pigsy became Sir Quigley Brokenbottom (Jonathan Winters), the Bull demon became King Gruesome, two bandits became the McSnarl brothers, Herman and Vermin, a cute child demon became Philo Fester, and Buddha, the Chinese goddess of mercy Kuan Yin, and Xuanzang became King Amo, Queen Amas, and Prince Amat. Minor characters were given well-known Western names; an old wizard became Merlin the Magician, and a massive warrior became Hercules. (Saiyūki used the line, “Your name is Hercules? I’ll call you Jerk-ules!” decades before Disney did in its 1997 Hercules animated feature.) And Saiyūki became Alakazam the Great, which was Saiyūki’s new name.

Alakazam the Great and Magic Boy had big publicity budgets. Globe spent the least on was now Panda And The Magic Serpent, possibly because it had the least to spend. Changing the film’s title from Hakuja-Den to Panda and the Magic Serpent added to the confusion, since little Panda and Princess Ba-Niang never appear in a scene together. A duck in the White Pig mob is given an imitation “Donald Duck” voice. Mimi the red panda becomes a cat – it’s not known if this was deliberately because red pandas are almost unknown in America, or accidentally because Globe’s editors didn’t recognize a red panda. (Mimi became the oddest cat that anyone ever saw.) Globe hired Marvin Miller, then well-known from starring in the 1955-1960 TV series The Millionaire, to provide the extensive narration. That was in Hakuja-Den – Tōei Dōga was not yet familiar with dubbing lots of dialogue – but Miller delivered it like a stuffy college professor giving a long, boring plot synopsis of a literary classic.

No matter. None of the three were a popular success, despite all of the advertising for Magic Boy and Alakazam the Great. The three were released almost on top of each other: Magic Boy on June 22, 1961; Panda and the Magic Serpent on July 8, 1961; and Alakazam the Great on July 26, 1961. They were considered “too foreign” by the American public. The first two were very slowly paced by audiences used to Disney’s features, and two of the next three from Tōei Dōga – 1961’s The Orphan Brother/The Littlest Warrior, and 1963’s The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (released in the US via Columbia Pictures) – were both too slow and too historically Japanese. (The 1962 feature, Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad/Sinbad, the Sailor, was both very slow and from a tiny American distributor, Signal International, that barely got it out to the public.)

No matter. None of the three were a popular success, despite all of the advertising for Magic Boy and Alakazam the Great. The three were released almost on top of each other: Magic Boy on June 22, 1961; Panda and the Magic Serpent on July 8, 1961; and Alakazam the Great on July 26, 1961. They were considered “too foreign” by the American public. The first two were very slowly paced by audiences used to Disney’s features, and two of the next three from Tōei Dōga – 1961’s The Orphan Brother/The Littlest Warrior, and 1963’s The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (released in the US via Columbia Pictures) – were both too slow and too historically Japanese. (The 1962 feature, Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad/Sinbad, the Sailor, was both very slow and from a tiny American distributor, Signal International, that barely got it out to the public.)

The failure of all three did not exactly doom Japanese animated features in America, but from then on, they were either bought for pennies as one-shot rentals for children’s matinees, or went directly to TV as kids’ Saturday-afternoon features, or after 1990 to the new anime-fandom video market. Even today, with the success on American TV of anime series such as Sailor Moon and Cardcaptors and Naruto, the most highly-rated theatrical movies like Akira, Grave of the Fireflies, and even most Hayao Miyazaki features can get only limited art-house bookings. It looked briefly at the end of the 1990s that game-related theatrical features like Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh! might break out of this ghetto, but they quickly faded back to niche-market fodder only. Basically, the American theatrical film market is not interested in Japanese features.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Yet today, a new generation raised on anime and manga (and led by more open-minded nostalgists) would die to get their hands on decent releases of the English versions. Panda and the Magic Serpent has been released to DVD a couple of times, but the print used to make both is absolutely shredded; Amazon offers Alakazam the Great through its Instant Video VOD service*, but it appears to be a just-competent VHS conversion; and the only way I know of to see Magic Boy‘s English version is to find and download a rip of an old TV broadcast.

It’s too bad, because there are fans who want to restore these classics and would gladly do so for no reward than the restoration itself; they just lack the resources and the authorization. Toei has made it very clear, in English, that they don’t want to be approached on the subject unless they can hear the jingle in your jeans.

*Amazon also has Jack and the Witch, I see. I’ll have to check it out! It never even got a VHS release, but has aired regularly on one of New Jersey’s local stations. …Meanwhile, Jack y La Bruja is on freaking Blu-Ray in Spain. BLU-RAY!! It’s a straight-up re-dub, but the only real difference between the US and Japanese versions was in the title cards, character names and songs, plus the US version ditched the opening narration that tied the story to, of all things, Beowulf.

Magic Boy is part of the Turner movie library. They showed it on TCM, but only once to my knowledge. We can only hope that they’ll realize what a jewel they have and replay it.

The other Toei features that had American release and have made it onto dvd aren’t worth buying. Like you said, they are terrible prints, and also the dubs and rewrites ruin the film watching experience. It’s better to watch online uploads of these for free, and save your money towards buying the Japanese dvds of these cartoons.

It’s nice someone at Turner (WB) remembers they have that film at all, TCM use to air a letterbox version of the film rather than in pan & scan like some channels did with Alakazam The Great (reminded FLIX aired that once). I managed to tape it one of those nights/early mornings once.

Alakazam The Great got a VHS and LaserDisc release by Orion (the successor of the AIP library, now with MGM) in the mid 90’s, so it’s as legit as that one got. As for Panda & The Magic Serpent, I consider that an “orphaned title” simply because no successor after Globe Pictures bothered to pick it up or do much with the property besides leaving it to languish as it did. Sad really (at least Public Domain gave it a home at all).

Speaking of Jack & The Witch on Amazon, another of Toei’s 60’s features, “The Great Adventure of Hols, Prince of the Sun” can be seen on Hulu in it’s dubbed (and pan & scanned) title “The Little Norse Prince”.

http://www.hulu.com/watch/168816

He is the brave young warrior & hero/protagonist together with his compatriots battles the forces of evil save the world protect the innocent & keep the peace & save the ancient world.

Fred,

much thanks for writing this. I love the Toei features, and really enjoy reading about them.

I wonder how The Orphan Brother/The Littlest Warrior did in japan. Its storyline is pretty gruesome; certainly not for children. i’m guessing that it is based on a well-known folk tale, but I still find it an odd choice for an animated film … especially one made in the early 60’s.

You wrote that “… Basically, the American theatrical film market is not interested in Japanese features …”. this is something that I refuse to believe. Good is good, and people want to watch good films. I’d love to know the real reason these films failed. Was it the poor rewrites and dubbing? Were they given small marketing and promotion budgets? Were they handled by “farm team” members of the film companies that distributed them? How long did they play in the theaters compared to other films released at the time? did they get a chance in big run theaters, or were they forced into the smaller theaters? Perhaps the biggest question is was Disney perhaps working behind the scenes to sabotage these films?

Gulliver’s Travels Beyond The Moon is a beautiful film. As slick as Disney, and very American in looks. There’s no way that film could have failed if marketed and promoted properly.

I don’t know that they necessarily “failed”. They didn’t become hits, but probably met the low expectations the studios had for them. Outside of Alakazam the Great, I believe that most of the Japanese animated features of the 1960s were considered fodder for “Saturday Matinees” – which were still in force throughout the 1960s. There was also a thriving non-theatrical market (i.e. 16mm films released to schools, hospitals, summer camps, church groups, etc.) that needed to be fed.

As these films had little financial value, they were probably picked up pretty cheaply. I’m sure Japan was proud to get any U.S release. Though MGM did not pick up anymore (though in fact, they had acquired Toei’s Doggie March but did not follow through to release it), United Artists picked up The World Of Hans Christian Anderson, Columbia released Jack And The Beanstalk and AIP released a slew of features directly to television.

Based on the newspaper ad above, and with an “all-star” voice cast, it seems AIP gave Alakazam a first-class domestic release. I don’t think anime got that treatment again until the recent Miyazaki films released through Disney.

AIP gave Alakazam a first-class domestic release

About as first class as a studio like AIP could go. But I agree, Alakazam was the only anime until the ’90s that actually seemed to get top-drawer studio localization treatment until Disney started releasing Miyazaki. Even earlier stuff that is remembered as being “hits” in the U.S. like Akira was really only marketed as an limited audience arthouse film.

In ’61 AIP was doing good business in drive-in movies. They could open on a Friday and be out of town Sunday night, and you could make up your own mind without any help from reviewers. I saw it, I understood clearly it was a foreign movie, and I liked it!

“The Littlest Warrior/The Orphan Brother” was not based on a folk tale, but on one of the first modern Japanese literary works; or more specifically, on a famous 1954 live-action feature adaptation of it. The literary work is the 1915 novel “Sanshō Dayū” or “Sanshō the Bailiff” by Mori Ōgai (or Ōgai Mora; 1862-1922), a career Army surgeon (he was a Lieutenant General when he retired) who had studied in Germany in the 1880s and wanted to introduce modern international literary styles into Japanese society. He specialized in stories about Japan’s past that were so bleak and depressing that they made Tōei Dōga’s adaptation of “Sanshō Dayū” seem like a comedy in comparison. The 1954 movie was directed by Kenji Mizoguchi, who had recently been “discovered” by the French cinematic critics as a master of Japanese cinema, and was winning awards at the Venice Film Festival. His 1954 live-action “Sanshō the Bailiff” was one of his last films; he died of leukemia a couple of years later.

I assume that the 1961 animated version was the result of Tōei Dōga’s decision to bring Famous Japanese Literature to children. You’re right; it is pretty gruesome. But the 1915 novel and the 1954 movie are much worse. Sanshō is one of the villains, by the way. The plot’s point, if it has one, is that you should always obey government officials, no matter how openly corrupt and brutal they are; both because they are your superiors, and because suffering is good for the soul. Reportedly Tōei Dōga’s animators hated being ordered to make the movie, and that it was a direct cause of the studio’s labor/management split that led to the younger animators like Takahata and Miyazaki organizing an animators’ union.

My column next week is about what I consider to be Tōei Dōga’s two best features of the 1960s; “The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon” and “The Little Norse Prince”. The former was bought by Columbia to become a Saturday children’s matinee feature only, and the latter was bought by American International and sold directly to TV. Disney did not sabotage them; it didn’t have to.

Fred Patten wrote, “… The plot’s point [of Sanshō Dayū], if it has one, is that you should always obey government officials, no matter how openly corrupt and brutal they are; both because they are your superiors, and because suffering is good for the soul …”

can the japanese word for government officials also be translated as animation executives?

EETEED said….

It’s hard to tell with that one, it was released by the Walter Reade Organization I recall, other than getting it’s share of editorial decisions such as replacing the music with whatever Milton and Anne DeLugg cranked out which was excellent in my opinion. The film might be seen as a good transition for the studio in doing sci-fi themes and settings as we would see in the coming years, though the film also started a trend of adapting further western literature like Puss in Boots, Treasure Island and Little Mermaid to follow.

JERRY BECK said….

Saturday Kiddie Matinees pretty much was the outlet for these things long before TV became the next dumping ground. I once had a 16mm print of Panda & The Magic Serpent that oddly contained the dialogue of the film written out as subtitles on the screen as it ran, I wasn’t sure if my print was used for some hearing-impaired/ESL type need but it was something.

Then I suppose a dub for that doesn’t exist.

Then of course the home video book of the 80’s that also proved a direction for Japanese cartoons to find a place on the “Children’s” shelf of any store in town.

I bet. Though when Columbia’s “Jack & The Beanstalk” happened to be playing in Washington, D.C. sometime in the 70’s, a Tulip plushie possibly made as a promo item showed up in this photo of their Bozo the Clown program! Not really relevant, but something

http://kidshow.dcmemories.com/Bozo620DD3.jpg

TED HERRMANN said….

At least you enjoyed your drive-in experience well there.

SOS!

Last night I was watching Future Boy Conan, and my multi-region dvd player died!

I can’t figure out what the best unit to replace it is. Oppo seems to be the number one choice, but with a starting price of $700 it is out of my range. Meanwhile all the other brands have more realistic prices, but reviews of them all seem to be split … half the people who bought them are happy with them, but the other half complain that they are junk that break down shortly after buying them (just like mine did).

=Can anyone recommend a region free dvd player at a reasonable price?

God I’ve been out of the DVD thing in years. Back when I started 14 years ago, I made sure to get a region-free player that required a lot of searching, though at the time, I went with cheap, no-name companies for my fix. I wish I could help you here.

Are there any English subtitle files online for Saiyūki? I wasn’t able to find any.

I don’t think the movie was ever translated at all, at least to my knowledge.

You guys totally need share post featured. This was a really good and interesting read. I’d like to think anime has become much more widespread and marketable now. Maybe when the rebooted Sailor Moon anime is simulcast worldwide, it’ll spread even FURTHER. That would be exciting. At the very least, I’d appreciate remastered versions of these films.

That would be nice. I usually have to copy the URL’s to my social networking places in that regard (though I also have the G+ widget on my browser too).

Sadly I feel these films fall into a niche within a niche. They weren’t Disney enough for mainstream audiences and they aren’t Anime enough for the American market.

Discotek Media is making strides in releasing older content, specifically Toei’s library of animated films and TV series on DVD so they are the best bet when it comes to acquiring these films for an English release.

“Sadly I feel these films fall into a niche within a niche. They weren’t Disney enough for mainstream audiences and they aren’t Anime enough for the American market.”

Those people are losers sometimes. Now you know what it feels like to get into indie/foreign flicks like I did once, nobody cares, even if you put in that much effort to find a theater that is playing that title in town than to go dozens and dozens (even hundreds) of miles away to a theater that does.

“Discotek Media is making strides in releasing older content, specifically Toei’s library of animated films and TV series on DVD so they are the best bet when it comes to acquiring these films for an English release.”

And I helped!

Jerry – I’m very interested to hear that MGM got the rights to DOGGIE MARCH, but never released it. How did you come across this information?

The 1950s-60s Toei films are some of my most favorite ones ever. Lots of magic in them.

When I worked for MGM/UA in the early 1980s, I dug around for all the information on animation the studio had the rights to. In doing so I came across a file related to DOGGIE MARCH. I found an original Japanese sales sheet for the film (which I “saved” and still have) and saw information relating to the fact that MGM acquired it. Unlike MAGIC BOY (which remains in the MGM (now Turner) library), I believe the option on DOGGIE MARCH lapsed and Turner does not own the US rights today.

“When I worked for MGM/UA in the early 1980s, I dug around for all the information on animation the studio had the rights to. In doing so I came across a file related to DOGGIE MARCH. I found an original Japanese sales sheet for the film (which I “saved” and still have) and saw information relating to the fact that MGM acquired it. Unlike MAGIC BOY (which remains in the MGM (now Turner) library), I believe the option on DOGGIE MARCH lapsed and Turner does not own the US rights today.”

Shame really, at least they didn’t let Magic Boy go at all.

Alakazam the Great was the first anime I can recall seeing–my second grand class and others in my school were adjourned to the basement of the school across the street, where we watched it via what must have been a 16mm print. This would have been 1976 or 1977; it took me a decade and a half before I was able to identify it, thanks to a Tezuka filmography in Anime UK. I still have a fond memory of the film.

Interesting you had to go across the street to watch it, what kind of school system was this? (don’t recall anything like that where I live so it’s new to me)

Four of the town’s nine public school buildings are concentrated on or opposite the town common, and IIRC the school across the street from the one I was attending at the time had/has a larger basement, and so provided a better venue.

Original title as Journey to the West/Monkey King & US version as Alakazam the Great.

As a child in the 1950’s & 60’s, our family would go to the drive in theatre on a regular basis. There was one film I remember because as it was playing my father decided to leave. Now, I guess he did not like subtitles. He refused to stay and watch it no matter how much I wanted to force the matter. My child’s eye remembers seeing amazing graphics, a princess and a white salamander. Today, at age 71, I was remembering that episode and thought to search asian movies 1958 w princess and salamander. Bingo! Got more than I expected and happy for it. I wish I could have seen the entire movie back then which was likely in 1961 when this post says it was more widely distributed than in 1958. Thank you for quenching my childhood quest for finding this movie.