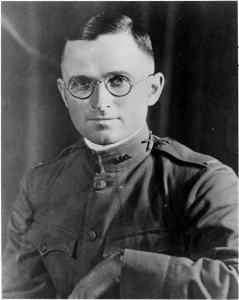

This story begins and ends with trains. In specific, it begins with trains being packed with artillery and munitions in the French countryside, and a young sergeant in the U.S. Army named Joseph Benson Hardaway. He was one among an irreverent bunch of soldiers from Missouri, members of the 129th Regiment, Battery D. It was August 1918, and the Germans were advancing on the battlefront.

Knowing that this is the same man who later helped launch a cartoon rabbit who bears his Bugs nickname, one might say that “the Huns” had gone too far and that “This means war!“ The soldiers crammed into boxcars and, with their big guns loaded on to flatcars, the train moved out to the front lines. Everything was packed in that needed to go, including horses and food, extra shoes and bottles of whiskey.

In a very short time their commanding officer, Capt. Harry Truman, had actually managed to turn around the battle fitness of this notorious “wild Irish” outfit. The soldiers had sent their previous commanders running to the hills, but somehow this plain-spoken officer had won them over by simply being reasonable and fair. Of all the units in the division, each one alphabetized A-B-C, it came as a surprise when Battery D logged the quickest boarding time.

In a very short time their commanding officer, Capt. Harry Truman, had actually managed to turn around the battle fitness of this notorious “wild Irish” outfit. The soldiers had sent their previous commanders running to the hills, but somehow this plain-spoken officer had won them over by simply being reasonable and fair. Of all the units in the division, each one alphabetized A-B-C, it came as a surprise when Battery D logged the quickest boarding time.

Of course, they hadn’t yet seen battle, but as they disembarked these young men—who had shown a disposition for drinking and fighting each other back at training camp—were steeling themselves to fight a very formidable enemy. This ragtag bunch suddenly performed at a mostly elite level in the boiling cauldron of wartime. They set up field positions and shelled the Germans, and the Germans fired back.

Since this was World War I, it should come as no surprise that each side used chemical weapons. When the shells exploded, they released lethal mustard gas. Sgt. Hardaway got to see firsthand some of the qualities that made Truman a leader, and in surviving the trials of war the entire unit developed an enduring bond that lasted for the rest of their lives. All the men loved Truman and he never forgot their loyalty.

Years later, working at the Walter Lantz studio, Bugs Hardaway must have recognized the drumbeats of war leading to another worldwide conflict. This time he served his part by making propaganda cartoons as the ‘idea man’ in a pairing with storyboard artist Milt Schaffer. Together the two constituted Lantz’s story department.

One can only wonder what Hardaway must have thought, knowing that the horrors of frontline battle were fast approaching for a new crop of wide-eyed farm boys, even as he dreamed up his typically corny gags from a sunny studio in Hollywood. His specialties were crazy characters and cheap puns. Below is a print gag, a pretty standard example of his style of humor:

When director Alex Lovy was drafted into the Navy, Shamus Culhane was brought in, setting off an interesting creative conflict with Hardaway. Culhane preferred more sophistication in the approach; he thought Bugs’ sense of humor was crude and formulaic. Yet somehow the collaboration worked, and the cartoons from these war years are viewed now as the Golden Age of Woody Woodpecker.

Meanwhile, the former captain of Battery D, Harry Truman, had advanced rapidly as a politician. At the start of WWII, he was Vice President under Franklin D. Roosevelt. He spent a good deal of time crisscrossing the country on official visits to bolster the war effort. Whenever Truman came to Los Angeles for a shipyard visit or a draft review, he had a festive reunion with men from his old unit. They loved to call themselves the Battery D Boys.Schaffer recalled in an interview with Joe Adamson that about sixteen of these veterans would “get together for an evening of poker and bourbon drinking, and Bugs would go to these things and the next morning he’d come and tell me about his friend [Harry Truman].”

This must have given Bugs quite a bit of studio cachet on mornings after his poker games. One can imagine the interest in any news Truman may have shared with the D-Boys over bourbon. And just as likely, knowing that Bugs was quite a storyteller, the sixteen veterans were probably regaled with stories about Woody Woodpecker and the Lantz studio.

Mel Blanc once stated that Bugs “had a snappy way about him.” From photos of that era, Bugs looked like a sharp dresser, even as he cut quite an imposing figure, but underneath that snappy tough-guy exterior were some old war wounds. Health issues lingered on from German gas attacks he survived, leading to a thyroid disease.

Over bourbon, these veterans who had made it home from the War over twenty years earlier were surely still grateful to reconnect with the only men who really understood the hell they withstood. And then, through reports coming in from radio and newspapers, they must have sensed what another generation of boys was enduring in Europe.

On April 12, 1945, FDR died and the nation mourned the passing of a leader who guided America so capably through the Second World War. Milt Schaffer recalled the moment: “I’ll never forget the day we sat in our little story room and it comes over the radio that Roosevelt died, and Bugs is just sitting there saying, Harry’s the President, Harry’s the President.”

On April 12, 1945, FDR died and the nation mourned the passing of a leader who guided America so capably through the Second World War. Milt Schaffer recalled the moment: “I’ll never forget the day we sat in our little story room and it comes over the radio that Roosevelt died, and Bugs is just sitting there saying, Harry’s the President, Harry’s the President.”

Truman finished Roosevelt’s term and then was reelected in 1948. From The White House came invitations to each of the Battery D Boys to attend the President’s inauguration. Truman wanted them all there, and train tickets were provided to every last man. Bugs traveled across the country to be part of the ceremony.

The trains arrived in Washington, D.C, quite a different scene from the boxcars that had carried them as soldiers thirty years earlier. After being sworn in, Truman’s Inaugural Ball was a big party that also served as a reunion of his old artillery unit. This was a black-tie affair, so surely the fancy glasses were filled with champagne, but as the night wore it is nearly certain that bourbon whiskey became the drink of choice.

In 1957, the man born Joseph Ben Hardaway died of complications likely stemming from his wartime exposure to chemical weapons. History remembers him for his role in naming Bugs Bunny, but on his gravestone are the two things that defined him in his lifetime: born in Missouri, served in battle in the 129th Field Artillery Regiment.

This post is dedicated to the memory of my mentor and teacher, Dan McLaughlin, who chaired the Animation Workshop during my three years as a grad student at UCLA. It was there that I became acquainted with Walter Lantz and began my scholarly work on his studio, and first met many other notables in animation largely through the generosity of Dan. Like Bugs Hardaway, he began in cartoons only after serving as a veteran overseas, and “wild Irish” would be as appropriate a term in describing McLaughlin as it was the nickname of Battery D. He was a recipient of ASIFA’s Winsor McCay Award for his life’s work. On Tuesday, he passed away in his sleep.

This post is dedicated to the memory of my mentor and teacher, Dan McLaughlin, who chaired the Animation Workshop during my three years as a grad student at UCLA. It was there that I became acquainted with Walter Lantz and began my scholarly work on his studio, and first met many other notables in animation largely through the generosity of Dan. Like Bugs Hardaway, he began in cartoons only after serving as a veteran overseas, and “wild Irish” would be as appropriate a term in describing McLaughlin as it was the nickname of Battery D. He was a recipient of ASIFA’s Winsor McCay Award for his life’s work. On Tuesday, he passed away in his sleep.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

There is one glaring error in this article.

When the Second World War began, Henry Wallace was the Vice-President of the United States.

Harry S. Truman was a Senator from the state of Missouri, where he had served since 1935.

There is some belief that Truman got his seat in the Senate through the courtesy and largesse of the Pendergast “machine”of Kansas City, Missouri. That is really neither here nor there.

Truman was selected by President Roosevelt as a running-mate for the 1944 election. Apparently, if FDB had had his “‘druthers”, he’d have stayed with Wallace.

But a lot of big-city Democratic Party “machine” politicians did not trust Wallace. He was too radical for their tastes. They prevailed upon FDB to dump Wallace, and pick somebody more mainstream.

FDR agreed, when he realized that the delegates at the Convention would not support Wallace for a second term at Blair House. He chose the Senator from Missouri instead–and the rest, as they say. . .

Wallace did prove to bee “too radical”, and challenged Truman in 1948, running on a third-party “Progressive” ticked with Senator Glenn Taylor of Wyoming. The “Progressive Party” was regarded even then as a front for the Communist Party.

He came in fourth in the popular vote, with no Electoral votes whatsoever. Nearly half of his votes came from the state of New York.

Thanks James; and yes, I should have begun that sentence, “Near the end of WWII, as VP” or “At the start, as Senator.” I’ll submit the correction to Jerry. Most of these visits to Los Angeles first occurred as you mention, as a Missouri Senator who chaired the “Truman Committee”, officially a Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. The L.A. area was a huge hub for building aircraft/weaponry, making it critical to the war effort, and therefore an obvious place for Truman to root out waste/corruption on his visits, plus to build his political reputation. Also, a good place to have Battery D reunions, with possibly the highest concentration of his former unit outside of Missouri.

Very good article but what is the Daffy Duck cartoon (or duck cartoon) shown at the top..

All the war-themed still frames that appear here are from the same cartoon, “$21 a Day, Once a Month.” The duck you see here was not a leading character, just one of many toy/animal characters that appear in this Swing Symphony.

So why didn’t Hardaway come back to Lantz when the studio re-opened in 1951?

I’ve never heard anyone provide a specific reason why, but my guess would be that Lantz always was needing to trim costs, and Hardaway was likely either a redundant expense (as more of a gagman paired with Schaffer) or too expensive, given his accomplished track record with Bugs B. and Woody W. The reason may also be deteriorated health; Hardaway suffered setbacks and died in early 1957. Perhaps there is a reader who knows more about the last years of Hardaway’s life? As an aside, Truman in 1957 became the first (former) President to visit Disneyland, further bolstering his animation credentials and his “travel mileage” to Southern California.

…Truman in 1957 became the first (former) President to visit Disneyland…

Hence the infamous newspaper headline, “Huey, Louie, and Dewey Defeat(s) Truman”.

Thank you for this candid description of my great, great uncle. I often wondered where my dad got his simple talent of drawing funny characters. – perhaps his great uncle. Joseph’s brother, Stanfield delBarco Hardaway moved from St. Louis, MO to Orlando FL in the late 1910s.

Best regards