If you ask a cartoon fan to name a character named Bolivar, the savvy enthusiast is keen to know that the unspoken St. Bernard in the Mickey Mouse short Alpine Climbers (1936) is the bearer of this unusual name. After Pluto drops into a snow bluff and freezes to an ice-blue color, Bolivar dutifully thaws him out by pouring brandy from his collar-mounted barrel straight into Pluto’s mouth. However, even the most astute pupil of animation will overlook the other Bolivar, the one that came first.

If you ask a cartoon fan to name a character named Bolivar, the savvy enthusiast is keen to know that the unspoken St. Bernard in the Mickey Mouse short Alpine Climbers (1936) is the bearer of this unusual name. After Pluto drops into a snow bluff and freezes to an ice-blue color, Bolivar dutifully thaws him out by pouring brandy from his collar-mounted barrel straight into Pluto’s mouth. However, even the most astute pupil of animation will overlook the other Bolivar, the one that came first.

To know more about him, try plumbing deeper into the early days of American animation, just after The Jazz Singer lit the town on fire, stoking the ambitions of Hollywood animators. Talking pictures were a future that many saw rushing toward them and some were betting that cartoons were next. The knowledge that The Jazz Singer was a big hit was manna from heaven for an array of starry-eyed dreamers. Simultaneously, multiple efforts were under way to figure out the technical details for synchronizing animation.

One of those dreamers who jumped at the chance was Pinto Colvig, whom I wrote about in my last column. For him, the advent of sound in film was the perfect culmination of his various occupations. He had starred in vaudeville in the Pacific Northwest and then ran his own animation studio in San Francisco. He played instruments, performed as a clown, worked in a traveling circus, did silly voices, drew comic strips, and after a move to Hollywood he used his skills as an animator to put gag-based visual effects in Mack Sennett comedies. From an article in Coronet profiling Colvig, the moment of opportunity was described this way:

Not long afterwards sound pictures hit Hollywood, and that was all Pinto was waiting for. Since he was a cartoonist and could make more sounds than anyone else in town, he decided to combine the two and make sound cartoons. He quit everything else, dug up all the money he could and with Walter Lantz worked out one of the first animated cartoons in sound.

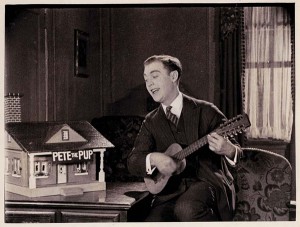

The cartoon they made was called Blue Notes and it was to be the first of a series starring Bolivar the Talking Ostrich. Colvig was the voice and he created the sounds, though no copy of the film or soundtrack is known to exist. If there ever was one person so deserving of the arrival of talkies—for whom the medium itself could synthesize his diverse talents—that person was Pinto Colvig. He even got to appear in the film as a version of himself.

According to his own autobiographical account, he was filmed as a “wandering minstrel clarinet player” and Bolivar was a pesty animated character who followed him around. By the end of the film they get into a tussle and then the ostrich runs off with the clarinet. Judging from his later vocal work for Universal and Disney, he squawked and talked and sang, enthusiastically giving voice to his creation with a “gearbox tenor voice,” as he described it.

According to his own autobiographical account, he was filmed as a “wandering minstrel clarinet player” and Bolivar was a pesty animated character who followed him around. By the end of the film they get into a tussle and then the ostrich runs off with the clarinet. Judging from his later vocal work for Universal and Disney, he squawked and talked and sang, enthusiastically giving voice to his creation with a “gearbox tenor voice,” as he described it.

In 1928 it was announced in Hollywood Filmograph that a new firm named Bolivar Productions would be releasing its animated short subjects through Movietone Pictures, a venture created by Fox-Case Corp. that was facilitating audio for cinema. Colvig’s hometown newspaper, The Medford News, wrote on December 28, 1928 that “the theater-going public will be given many laughs via seeing Bolivar and ‘Pinto’ perform on the screen.” The productions would also involve Lantz as a principal and, according to the article, “Charles Diltz, well-known comedy director, will direct the series.”

The previous year, Diltz was the director of a Bray two-reel comedy, Yankee Doodle, and was the screenwriter of Out All Night, a Universal feature. Presumably the Bolivar series would have continued with a significant portion of live-action filming directed by Diltz with animation overseen by Lantz and Colvig.

Though Colvig got all the roles in this one, Lantz had been a bit of a star in his own right. Not only was he a former Bray director, but he had also starred in the Dinky Doodle films (in New York) and a live-action comedy, Barnyard Rivals (1928). Between both men, they had a rather deep technical knowledge of animation and filmmaking, with the capacity to make the transition to sound, though Colvig described the secretive nature of Hollywood competitors with some despair, saying “the industry acting like a selfish baby with a new toy.”

“Barnyard Rivals” (with Walter Lantz on the right)

Steamboat Willie was in production during summer of that year with a November debut. The Colvig-Lantz effort was in early development at roughly the same time, possibly slightly earlier. Even with Mickey Mouse prevailing, the Bolivar team was among the vanguard of animators who challenged Walt in crossing this milestone. Mickey screened in New York City as a triumph, while the ostrich fizzled.

Admittedly, Bolivar is a bit of an ugly bird, more gangly than cute, and seemingly with none of the popular geometry shared by Felix, Mickey and Oswald. I’m basing this on the only image of Bolivar I’ve ever seen, from an eBay sale (June 7, 2013) of a drawing signed by Colvig and dated October 1928, which he mailed to Betty Lou Elwyn. A collection of Pinto Colvig materials is archived at the Southern Oregon Historical Society in Medford, Oregon. Records indicate that a few rare drawings of Bolivar are held there, but as of this writing those are not available to view online.

Admittedly, Bolivar is a bit of an ugly bird, more gangly than cute, and seemingly with none of the popular geometry shared by Felix, Mickey and Oswald. I’m basing this on the only image of Bolivar I’ve ever seen, from an eBay sale (June 7, 2013) of a drawing signed by Colvig and dated October 1928, which he mailed to Betty Lou Elwyn. A collection of Pinto Colvig materials is archived at the Southern Oregon Historical Society in Medford, Oregon. Records indicate that a few rare drawings of Bolivar are held there, but as of this writing those are not available to view online.

That has only added to the enduring shroud of mystery that hangs over this early cartoon. So few among us today have even glimpsed Bolivar. Based on the 1928 sketch he made for Elwyn, the “Talking Ostrich” had thick bowlegs, tiny wings, a derby or tophat, and he smoked cigarettes just like Pinto—or perhaps that was only an embellishment for Ms. Elwyn?

It is interesting that Colvig continued to keep the story of Bolivar alive within his professional narrative. By the time the magazine profile appeared in Coronet, in the November 1944 issue, Colvig had racked up some sterling professional credentials in film—making a wealth of comical sound effects and serving as a voice artist for several classic Disney characters, including Goofy—yet he still chose to count Bolivar as a career achievement to the magazine writer.

By contrast, in later years Lantz said almost nothing about Bolivar. There were certainly anecdotes from the 1920s he enjoyed sharing, and I heard some of them, such as about his time at the Sennett studio. But on the topic of Bolivar, I never remember him bringing it up.

Colvig and Lantz became acquainted in Los Angeles, and Lantz even took over an animated sequence on the film The Goodbye Kiss that Colvig relinquished. Mack Sennett liked his work and hired him until December 1927. Then, unemployed again, he was free to team up with Colvig in 1928, the year when Bolivar the Talking Ostrich came to life. In fact, this was not even Lantz’s first experience with a movie sound experiment. As early as 1924, when he was an on-screen star for Bray in New York, Lantz had played ukulele for a filmed Fox sound test.

Colvig and Lantz became acquainted in Los Angeles, and Lantz even took over an animated sequence on the film The Goodbye Kiss that Colvig relinquished. Mack Sennett liked his work and hired him until December 1927. Then, unemployed again, he was free to team up with Colvig in 1928, the year when Bolivar the Talking Ostrich came to life. In fact, this was not even Lantz’s first experience with a movie sound experiment. As early as 1924, when he was an on-screen star for Bray in New York, Lantz had played ukulele for a filmed Fox sound test.

To complete a Bolivar cartoon, however, Colvig and Lantz would face a great deal more complexity and have to fully engage the nuances of the technology they apparently licensed via Movietone, a Fox-Case company. That is where the trail goes cold, in terms of an historical understanding of what they accomplished. I am not aware of anyone having details about Blue Notes or the terms of a business partnership named Bolivar Productions. If anyone does know more or has any piece of information to share, please post a comment below.

Lantz’s implicit dismissal of Bolivar, by virtue of not elevating the story in his personal narrative or even mentioning it in his numerous publicity opportunities, seems to show that Bolivar was more the effort of Colvig. However, the story that Walter Lantz did love to tell was how (when he was largely unemployed in the early half of 1928) he had saved enough money from his thriving years as a director in New York to enjoy Hollywood parties and some impressive socializing with stars and studio heads—oh, how he enjoyed rattling off the names, the credentials of his easy access to silent movie royalty through his friendship with Bob Vignola, who hosted Walter when he moved out to Los Angeles the year before.

Without regaling you with an oft-repeated story, I will simply say that his Great Gatsbyean leisure life, as a sort of Nick Carraway type, made him enough of a regular attendant at celebrity parties and poker games to establish a regular line of conversation with Universal Pictures studio boss Carl Laemmle. After distractions with subcontractors fighting over his Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series, Laemmle began to think highly of the young gentleman from New York whom he always saw at the card table watching the games, amiable yet prudently out of the main spotlight.

Without regaling you with an oft-repeated story, I will simply say that his Great Gatsbyean leisure life, as a sort of Nick Carraway type, made him enough of a regular attendant at celebrity parties and poker games to establish a regular line of conversation with Universal Pictures studio boss Carl Laemmle. After distractions with subcontractors fighting over his Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series, Laemmle began to think highly of the young gentleman from New York whom he always saw at the card table watching the games, amiable yet prudently out of the main spotlight.

I presume that people at these parties would ask him, just as people do now, “what are you working on?” A terrific answer for Lantz would not have been that he was “between jobs” but rather that he was a co-founder of Bolivar Productions—regardless of how shoestring an operation it may have been—and that he was right on the cutting edge of unveiling a new cartoon star, a talking ostrich. That would have surely packed some wow-factor, especially with Steamboat Willie arriving later that year.

The weekly poker party he frequented saw its share of Universal notables, so it’s possible that Charles Diltz was recruited here to add his talents to the Bolivar start-up. If Lantz had managed to create enough dazzle in the room about his forthcoming cartoon, that might have been enough to really catch Laemmle’s attention. After all, the phenomenon of Mickey Mouse sound cartoons soon came to upstage Oswald, and Lantz’s collaboration with Colvig was a perfect calling card for his sophistication in this emerging field.

Walter Lantz took a role on the George Winkler-produced Oswalds, but it was through his personal relationship with Laemmle that he scored the ultimate feat: he was given control of Universal’s animation division. At this point, with such a huge opportunity given to him, the upside of continuing with Bolivar the Talking Ostrich must have seemed meager in comparison, and besides there was apparently no further interest from Movietone.

Surely Colvig had more invested in the character since it was his own creation. However, the assumption of Lantz into a management role at Universal was a score for Pinto, too. He got drafted on to the Oswald creative team and he was given a significant role making the soundtracks for the cartoons, even serving as the voice of Oswald. By the end of 1930, this was his stepping-stone to greater things when he left for the Disney studio and became a legend for his voice work there.

Over time, Bolivar the Talking Ostrich was left in the dust, and in truth he was never well known in the first place, having laid an egg on arrival. Yet the gregarious Colvig arguably chatted up the memory of his first “talking” part in cartoons. In 1936, when the St. Bernard appeared in Alpine Climbers, the rescue dog had a nameless supporting role with Mickey, Donald, and Pluto. But then something interesting happened.

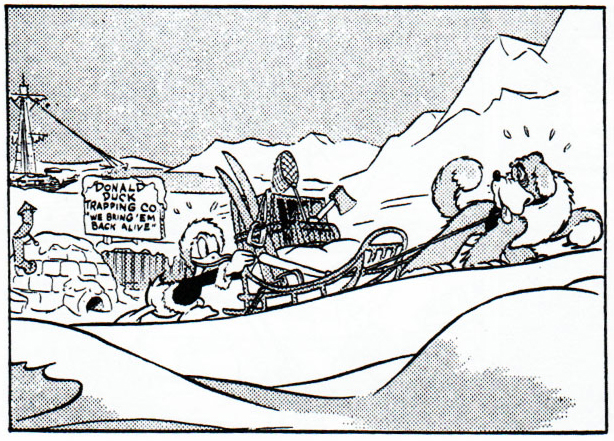

The Donald Duck comic strip by Al Taliaferro co-opted the St.Bernard to appear. The Disney strips would at times refer to the animated cartoons to find themes or characters to use. And so, in March of 1938, he suddenly appeared as a dog guarding apples that Donald is taking. Then, a few months later he appears again in a multi-part adventure in the snowy Antarctic based on the animated cartoon Polar Trappers (1938), which starred Donald and Goofy (voiced by Colvig, of course). The St. Bernard began to be called Bolivar in print.

This name was then carried on and continued by others, from Carl Barks to even David Gerstein more recently. There have been theories kicked around about how Bolivar got his very unusual name, but I believe the answer is probably quite simple. Taliaferro may have used it as a tribute to Bolivar the Talking Ostrich, a complimentary nod to its creator Pinto Colvig, well known around the Disney company.

That connection between one Bolivar and the next would be much easier to discern were it not for the fact that the original ostrich character has become so obscure that he’s virtually been scrubbed from the historical record. It is time to remedy that and to shine some light on this long-forgotten character. Here’s hoping the right person reads this and recognizes the name Bolivar on some old, time-worn treasure just lying around unnoticed.

With acknowledgements to the Southern Oregon Historical Society. The quotes above are Pinto Colvig in his own words from his memoir, It’s A Crazy Business: The Goofy Life of a Disney Legend, published by Theme Park Press and edited by Todd James Pierce. Special thanks to David Gerstein.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Great piece again, Tom thanks. The only thing of interest I could add is that Colvig and Lantz attempted to sell Bolivar to others in the second half of 1928. Before Warner Bros. began distributing cartoons by Harman-Ising Pictures, Colvig arranged a meeting to demonstrate Bolivar. Present were Jack L. Warner and Leon Schlesinger, and Colvig accompanied the presentation with his own comic efforts, supplying sounds vocally and musically. Apparently he was far funnier than the material he was hawking, because he reduced J.L. and Leon to helpless laughter, and they ended the meeting by saying to Pinto, “You’re all right, son!!”….but, alas, no sale. Just a few months later, in mid-1929, Harman and Ising screened their Bosko the Talk-ink Kid pilot film and the rest is history. (This anecdote was in a 1939 Paramount official biography of Pinto, released in publicity about his move to the Fleischer Miami studio.)

Thanks Keith, I really appreciate your mention of that. I was not aware of this Paramount publicity bio. There is a version of this story that Colvig provides on page 38 of It’s A Crazy Business: “I had tried to interest [Schlesinger] in getting me a Warner Brothers’ release on Bolivar. I had the film completed, but the music, dialogue, and sound effects had not yet been put into it. Schlesinger was interested, all right. He even made arrangements for Jack Warner to see the picture, with me on hand to explain the sounds and music that were needed. I shall never forget the day when the three of us sat inside of that small projection room on the Warner lot. While the pictures of Bolivar and me cavorted about on the screen, I sat there watching and supplying all of the dialogue, sounds, and music. I played my clarinet, kicked film cans and chairs, spoke my own lines of dialogue, and squawked in a guttural voice for Bolivar. Schlesinger and Warner seemed to get a kick out of it. I could hear them laughing and it made me feel mighty good. Not until some time afterwards did I learn that during the showing of the film, they had kept their eyes on me, watching my wild antics while supplying the sounds. They had forgotten to look at the cartoon!”