Then, around 1914, he started to draw sequentially, a humble beginning to his life as an animator and ultimately a millionaire producer. He made some crude animation even before he saw his first theatrical cartoon. Walter attributed his frame-by-frame experiments to another correspondence course, the illustrious mail-order lessons by Charles Landon. As Walter described it, he drew each page “with crosses on it” to serve as registration marks. Without the benefit of photographic equipment, the results could only be viewed by flipping.

The course had limited value because Landon knew almost nothing about animation. However, the lessons did have one lasting impact. In his Lantz biography, Joe Adamson wrote, “Enlisting the aid of one of the quarry’s able-bodied men, Walter constructed a drawing board according to specifications, with an eight-by-ten-inch glass window in the center to allow light to shine through several sheets of paper.” A kerosene lamp underneath (and between his legs) did the trick, so long as he didn’t light himself on fire.

He made his way to New York City a short time later, becoming an assistant to George Stallings in 1916. It was challenging to attain a working knowledge of animation without studio employment, so this opened a door for him. Kids might avail themselves a simple education through mail-order programs, but these were really geared for print cartoons. The Landon School was often regarded as the best of them and the W.L. Evans School was a more reasonably priced alternative.

To read these historic courses, full reprints have recently been published as books by John Garvin. It is known that Disney animators were among the eager pupils taking the Evans program as kids, including Ward Kimball. However, it has not been part of the official narrative of Walt Disney that he, too, may have been familiar with the course material. To connect those dots requires some backstory to understand how this could have been overlooked for many years.

Charles Landon and W.L. Evans ran their correspondence schools from Cleveland, Ohio. Despite initial plans to collaborate, they went their own ways as competitors. There were dozens of other cartoon courses in operation through the mail, but these two evolved and became nationally prominent in the ‘teens and twenties. The evidence of the lessons themselves suggests it was Evans who decided to promote animation more seriously as an applied extension of cartooning.

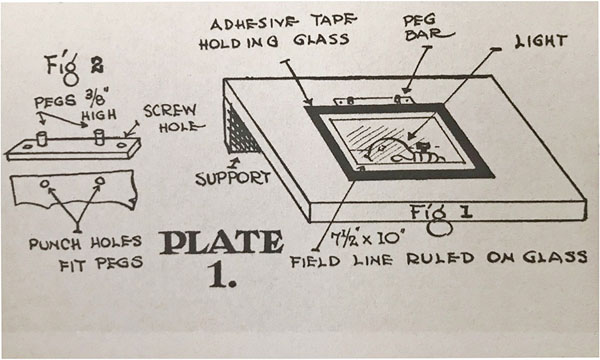

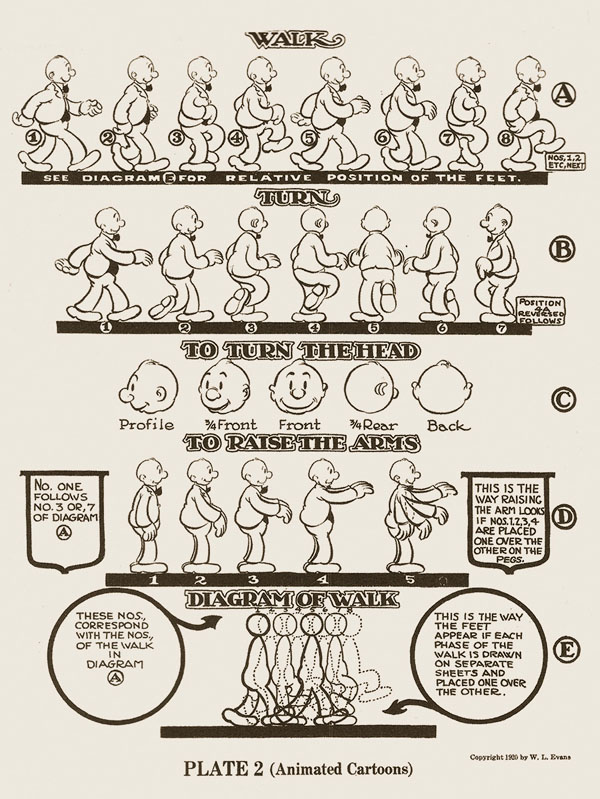

Around 1920, judging from the first copyright, an intriguing new section was added to the end of his course. For students who remained in the program and received all nineteen lessons, they got How To Draw Animated Cartoons without any fanfare that the course was leading here. To be clear, this was not a patronizing final lesson in making flipbooks. It laid bare the essentials needed to get started in independent filmmaking, showing how all parts of a studio worked. It presumed no less than the industry standard for animators: a drawing board with inset glass, hole-punched paper, sheets of celluloid, and an overhead camera stand.

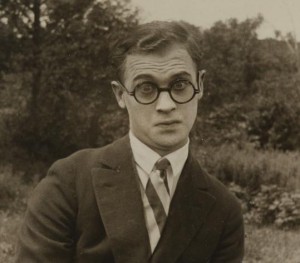

Bill Nolan

The lesson went on to provide expected salary ranges for different industry positions and it gave the addresses for six New York City studios where someone could seek work. It also gave the address for a New Jersey studio run by Bill Nolan. Quite simply, it seemed prudent for an aspiring animator to move closer to this metropolitan region. “It is not always convenient to come to New York City to work,” the lesson recognized, “but there is always a chance in your home town and in the neighboring towns. Your local theatre might be interested in a ‘Leader’ for their show.”

Within this passage, there’s a small clue that should raise an eyebrow. Why did W.L. Evans, who lived and worked in Cleveland, write “come to New York” and not go to New York? The way it’s written suggests the writer of this lesson is in New York and a reader would therefore “come to” join him. That may be a case of reading too much into a single phrase, but yet there’s more.

New York City in 1920

For those readers who might take his advice to produce an animated leader for a local theater, there’s a confession about how prohibitive the cost will be, especially for his students who are mostly children. It states, “The cost of a motion picture camera and cartoon outfit is beyond the means of the average student, but there is a concern in New York City which makes a business of photographing cartoons for artists.” The name of the business was Screen Sketching Service.

Once again, with its location in New York, this would seem to dim the prospects for students living anywhere else who would therefore face costs beyond their means. Nonetheless, around the same time as Animated Cartoons was added to the Evans course, that’s exactly what Walt Disney opted to do. He started out making content (not dissimilar to making a ‘leader’) for a local Kansas City theater and then ran himself heavily into debt building an animation studio comprised of fellow young artists. With a few exceptions, Disney and his crew looked like they were skipping high school to work there as junior animators.

It is well-known that he consulted Animated Cartoons, the E.G. Lutz book, for guidance. This is established in a letter Walt wrote to Irene Gentry, Acting Librarian for the Kansas City Public Library, to show his gratitude that he obtained his “first information on animation from a book written by H.C. Lutz” [sic] which he tells her he once checked out of the library. This consequential book and the Evans lesson were both available by no later than 1921, a formative period for him.

It is well-known that he consulted Animated Cartoons, the E.G. Lutz book, for guidance. This is established in a letter Walt wrote to Irene Gentry, Acting Librarian for the Kansas City Public Library, to show his gratitude that he obtained his “first information on animation from a book written by H.C. Lutz” [sic] which he tells her he once checked out of the library. This consequential book and the Evans lesson were both available by no later than 1921, a formative period for him.

Considering that Disney was a bit of a Pied Piper, drawing other cartoonists into his big dreams and wild schemes for a studio, it certainly seems credible that someone he knew had taken the Evans course and gotten to the final lesson. “Hey Walt,” that kid might say, “you gotta see this, it’s all about animation.”

There’s a decent chance that kid was Carman “Max” Maxwell, who at the age of 19 responded to Disney’s newspaper ad seeking animators. From the Jackson County Historical Society’s journal, we have an account from Ron Green that “Maxwell had done cartooning for his high school yearbook and had completed some correspondence courses with the W.L. Evans School of Cartooning.”

Even just speculating that this did happen and Disney was aware of the Evans lesson through Maxwell, it does not diminish the central importance of the Lutz book. It merely poses the idea that this other reference source also informed Disney. In fact, this line of thinking leads to a tantalizing passage on page 13 of John Garvin’s book:

It’s not clear how long Evans operated his school. By 1921 he had added a section titled “How to Draw Animated Cartoons” (reproduced on page 183). One of Evans’ students, William Nolan, provides a direct link to Walt Disney, who reportedly took Nolan’s course on animation* [4] “Biography of Walt Disney (1901-1966), Film Producer”. The Kansas City Public Library.

Garvin came across something in his research that led him to write that Disney “took Nolan’s course” and attributes this to biographical material by the K.C. Public Library, though on inquiry he clarified this was based on secondary sources. I’m eager to look at this a bit closer because, to my knowledge, Nolan did not offer a correspondence course in animation. However, it’s not the only time I’ve heard it mentioned.

In a way, it’s a bit of a legend. If it’s true, why hasn’t the internet turned up a copy? So this is where I need to tap the hive mind of Cartoon Research readers. Is anyone aware of a Bill Nolan-authored course from this time period? (And no, not his book, Cartooning Self-Taught, which was published a decade and half later, much too late for Disney to have read it in Kansas City)

I suspect I know the answer to this question. There is no Nolan course, at least not one that appears under his name, because he was the uncredited writer of How To Draw Animated Cartoons. It makes sense that Evans, having no experience as an animator, contracted Nolan to design this final portion of the correspondence course. Nolan had his early career in and around New York City, all of which is documented in a comprehensive post by Bob Coar.

Assuming that Garvin is right, that a young Walt Disney “reportedly took Nolan’s course on animation” then it stands to reason that Disney did not know this section was authored by Nolan at the time he read it. However, when Walt spent time in New York in 1928, he met Bill and the two became acquainted over business discussions. By that point, if he hadn’t already been made aware, Disney would surely learn that Nolan had ghostwritten for Evans.

If animators, including Walt Disney, would loosely use the term “Bill Nolan’s course,” I believe they were referring only to this last lesson in the Evans course. And finally, this isn’t just conjecture on my part. I have direct evidence, preserved in an interview with another early animator, that Nolan was indisputably the author of How To Draw Animated Cartoons. I’ll save that story for my next post.

The History of Cartoon Instruction Series offers the complete lessons of The W.L. Evans School of Cartooning and Caricaturing, compiled by John Garvin. The book is currently available on Amazon, published by Enchanted Images Inc. including 16 pages of How To Draw Animated Cartoons. The individual illustrations, or plates, hold copyrights of either 1920 or 1921, making it unclear if the animation lesson was first released in 1920, with additional plates added the next year, or if Nolan provided drawings to Evans incrementally to facilitate a 1921 release.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Nice connect-the-dots article, Tom.

FABULOUS addition to the early history of animation instructionals !!

I wonder if any further clues to Nolan’s authorship of “How to Draw Animated Cartoons” might be contained in the lesson itself. For example, the lettering in Plate 1 is very distinctive; the central horizontal beam of the letter E is longer than the others (ordinarily it would be shorter) and has a bit of a curve to it. Is there any evidence that Nolan drew his E’s that way? Or would Evans or one of his assistants have done the lettering in-house prior to publication?

What’s certain is that Nolan’s influence on the art of animation is more profound than anyone has hitherto realised.

I had the same inclination to have a ‘forensic’ look at the lettering for clues, but it’s inconCLUE-sive. The peculiarities of those E’s, for instance, are not even consistent within the lesson itself. Plate 1 and 2 seem to be from 1920 and the other Plates have 1921 copyrights. So they were not even inked at the same time. The different approaches to the inking and lettering make me think (as you mentioned, Paul) that Nolan supplied pencil drawings that maybe the staff at the Evans School cleaned before W.L. Evans would then submit to the copyright office. That, at least, would explain the stylistic variations.

I was just thinking that if Disney ever does an animated series based on Oswald, the crew should also take influences on the non-Disney that Nolan did at Lantz (if they can do that without legel issues). After reading this article, I say they really should study those for future Oswald projects.

It’s a shame that the Oswald series that Matt Danner was going to produced got cancelled. After being impressed with his “Three Caballeros” series (which sadly won’t get another season), I have his trust on doing a good job on the lucky rabbit.

From the look on his face, I’d guess the shorts Walter Lantz was in in the 1920s were too tight.

I would just like to thank Hans for his comment.

(go back up and read the photo caption for full effect)

This was a very intriguing read, Tom. It would be interesting if proof of the course does turn up assuming it actually existed.

Danielle, the good news I can give you is that the proof is arriving very shortly. I’ve turned in my follow-up article and Jerry is now editing in web-format for its appearance here on Cartoon Research. So, keep checking in for the big reveal, an Oswald the Lucky Rabbit animator who made it very clear Nolan was the author of this W.L. Evans animation lesson. In fact, this animator worked with Nolan at Universal, so was in an excellent position to have knowledge of this directly from the source. Hmm, maybe that drops a big enough clue about who this was. Anyone want to post a guess?

Tex Avery?

A great guess, but not Tex.

Never knew what Bill looked like ’til today! Unmustachioed Walt is pretty funny. Both are very influential on me, as well as “the other Walt” (even as Harold Lloyd).

HI, is Bill Nolan, William Nolan owner of Nolan Scenery Studios out Brooklyn in the late 50s?