No one would have believed in the last years of the 60’s that cartoons and comics were being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than Bob Clampett’s and yet as mortal as his own…

Although there were plenty of indications of what was to come, it is generally agreed that the 1960s was the moment when the attention of the artistic avant-garde turned its shrewd gaze to “minor” forms such as comics, advertising and even cartoons. The phenomenon was named “pop art” and under its influence serious intellectuals like the Italian Umberto Eco wrote about Dick Tracy’s ethics, the Louvre hung Krazy Kat next to the Mona Lisa, Tex Avery discovered how big he was in France and Andy Warhol produced hundreds of soup cans -without soup inside. In general, the hard-working members of the cartoon industry reacted with suspicion to the sudden attention their works generated in an audience that a few years earlier would have preferred to get knifed rather than be caught reading comics, and few failed to see the way the term “pop” seemed to inevitably attract its partner “kitsch”. Some of them even begun to suspect that their work was being studied less as an artistic phenomenon (which I don’t think they minded too much) than as a social symptom. Or something worse, as John Romita learned when he discovered enlargements of his comic panels signed by someone else in prestigious art galleries.

However, here and there, in a relatively small proportion, a strange counter-phenomenon occurred. Some of the artists recently arrived to these “minor forms” from the avant-garde, got their comeuppance: they were trapped by the gravitational mass of the studied object and ended up producing serious Pop. I mean, real comics or cartoons and not their cultured commentary. Their work was erratic, had ups and downs and, somehow, they kept a foot on the old world they had come from -along with some critical distance- that we should also be grateful for.

Despite I’m sure the story has been repeated with different actors all over the world, this article is about the adventures of three Argentines, and their particular connections with animated cartoons. Here we go.

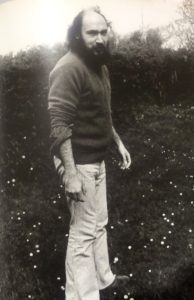

Rodolfo Azaro (1938-1987) is one of those artists who are always preceded by the word “atypical”. Although he is the one who could be most identified with the institutional art field of the trio, his entry on that world is strange to say the least: Azaro was a dentist and his work with the drill, recreating fangs and molars, excited the imagination of some of his clients, such as the painter Luis Wells. Soon after, Azaro began to participate in group exhibitions and competitions, in which he coincided with the emerging generation in the second half of the 1960s.

Like other artists of the time, he went pop around 1966, “approached with freedom and irony the primary structures” in 1967 and participated in the show Experiencias 68 of the Torcuato Di Tella Institute (the Di Tella was the great center of experimentation of the Argentine avant-garde and under its auspices the great Comic Biennial of 1968 was held). However, it seems that Azaro never quite fit in anywhere.

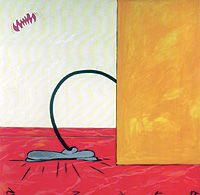

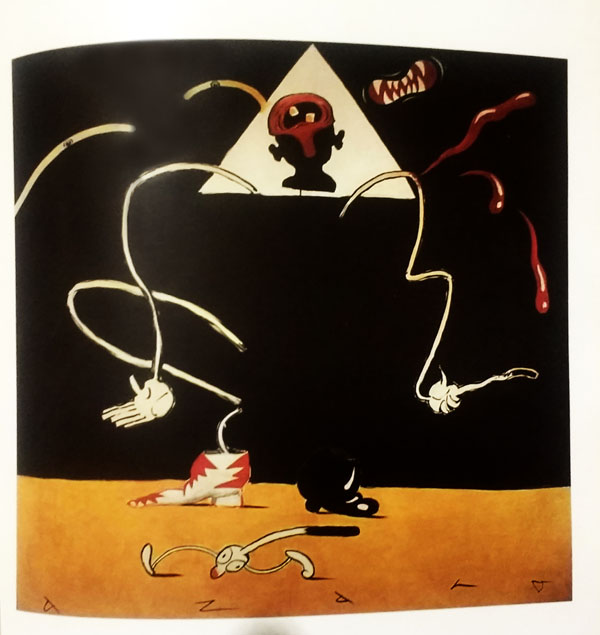

Rodolfo Azaro’s “Trayectoria de una pelota” (1968)

His work Trayectoria de una pelota (Trajectory of a ball), in which aluminum strips freeze the movement of a ball bouncing against the floor using typical cartoon resources, won alternatively a first prize and the following review: “Rodolfo Azaro shows a boring aluminum structure arbitrarily opposed to a pair of paddles and rubber balls. The structure, however, fails to dignify the paddles, nor do the paddles dignify the structure. Azaro insists on subtleizing already byzantine investigations, whose sterilization is predictable. ”

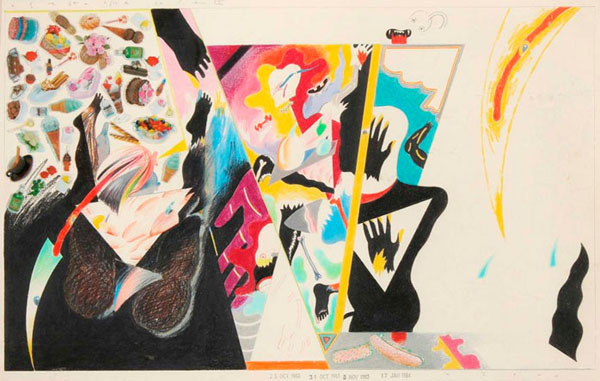

Azaro’s clip painting.

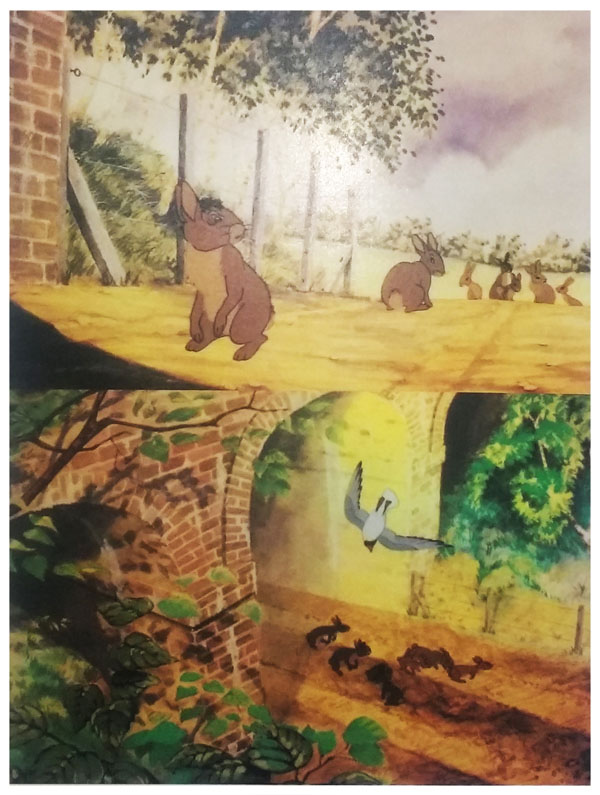

The credits that confirm Azaro’s passage through the British animation scene are few but convincing: backgrounds in “Watership Down” (Martin Rosen, 1978), color in the TV movie “The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe” (Bill Melendez, 1979), airbrush effects in “Heavy Metal” (several directors, 1981); productions where he appeared credited as “Rodolpho Azaro” or even as the more giggly “Rudolfo”.

Paradoxically, Azaro does not appear in the credits of the only film that several reviews about his work coincide in celebrating: Alan Parker’s The Wall from 1982 (with animated segments designed by Gerald Scarfe). The accounts of his collaboration in this film are quite conflicting and range from those who see Azaro’s imprint in every frame (citing more specifically the sequence of the “flower lovers”) to those who speak of a minor collaboration, restricted to the backgrounds.

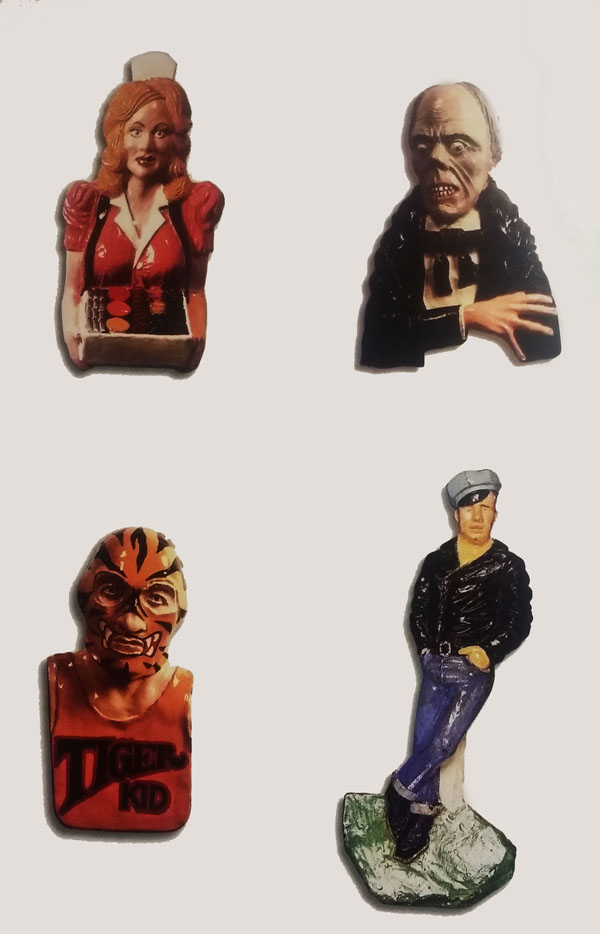

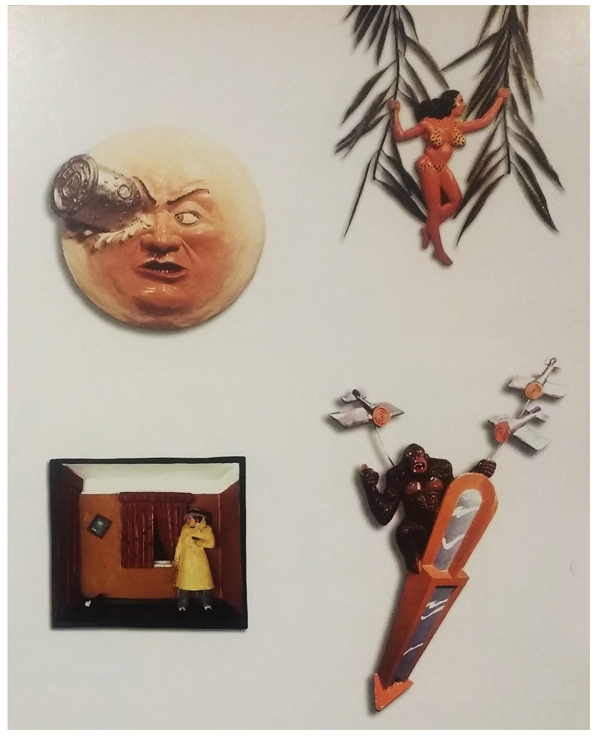

Around the same time, Azaro put all his talent as a miniaturist (and his drill) into the creation of polyester resin brooches-sculptures.

In this field, he seems to have shone as a more personal creator. One of his works (a “Marlon Brando” brooch) can be seen on Elton John’s lapel, decorating the cover of the artist’s Greatest Hits.

Elton John using one of Azaro’s brooches.

“The pieces are happenings, moments of life captured by Azaro’s eye as if they were photograms,” wrote the London critic. For his part Azaro complained, “I’d love to make the characters talk, that they could exclaim ‘Follow that car’ or ‘What’s a pretty girl like you doing in a place like this?'”

Azaro returned to Argentina for good in 1984. He participated in group exhibitions and held solo shows with spontaneous drawings, sketches, writings, paintings and small sculptures.

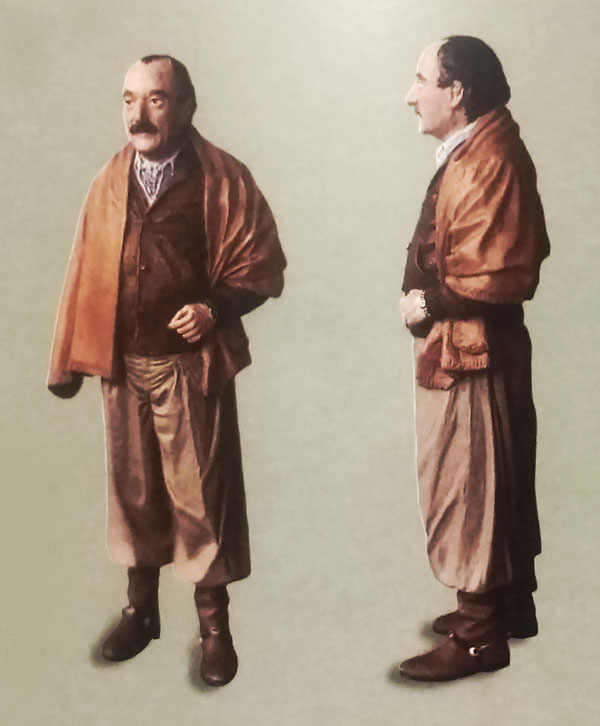

One of Azaro’s sculptures

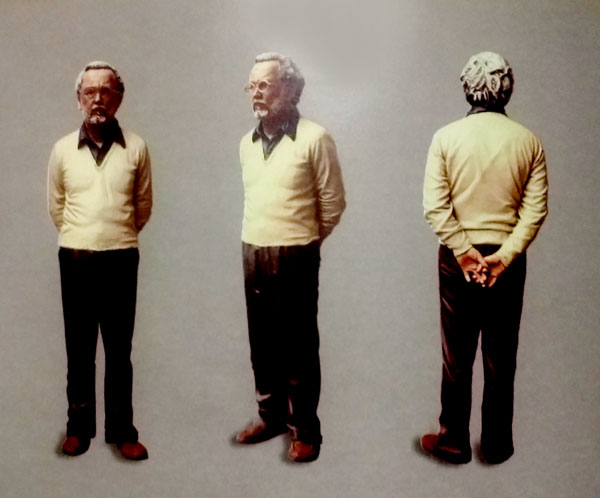

Sculpture portrait in resine of Artist Osvaldo Giesso

Sculpture portrait in resine of Daniel Azaro.

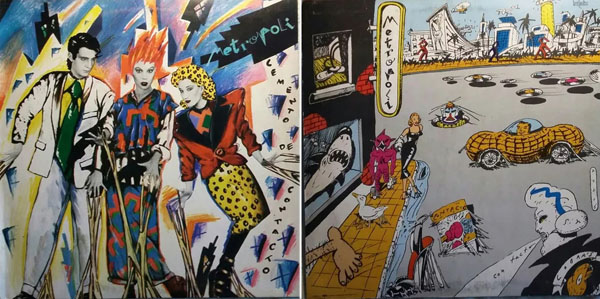

Cover album for “Metropoli” rock band (1985)

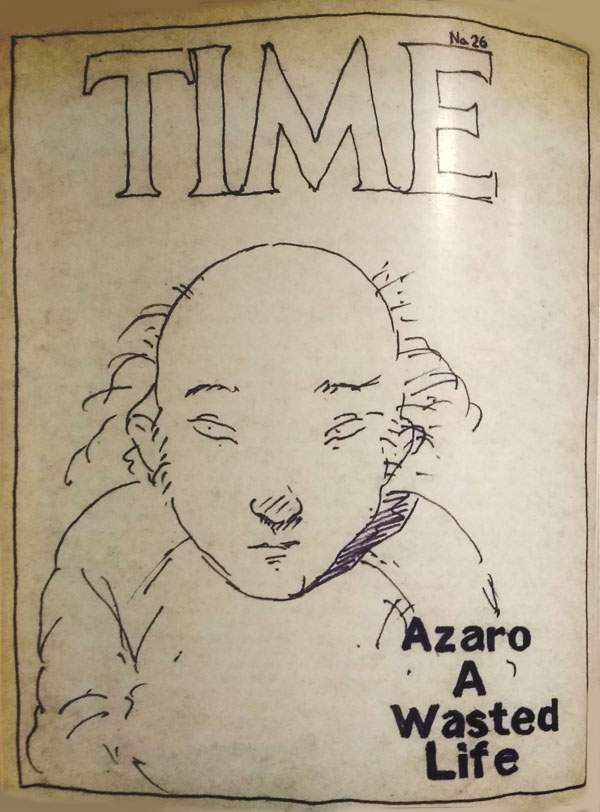

His last solo exhibition, entitled “Rodolfo Azaro Bop bop bop be bop”, opened in 1986 at the Centro Cultural Recoleta. One of his last drawings is a self-portrait of him smiling from the cover of Time magazine, accompanied by the title “Azaro, a Wasted Life”.

“An artist of a talent that surpassed his ability to organize it and spilled over, excessive, over every waking moment and suffering from insomnia, listening to radio, over-informing himself, taking note, carefully, of human stupidity,” wrote artist Américo Castilla after his death in 1987.

In 2004, Rodolfo Azaro had a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, which helped the visual arts world to claim the artist as their own.

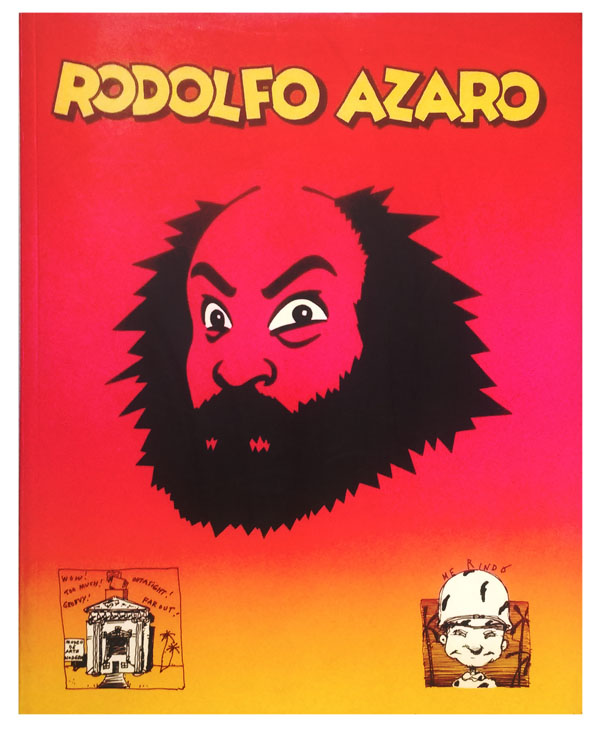

Azaro’s exhibition catalogue

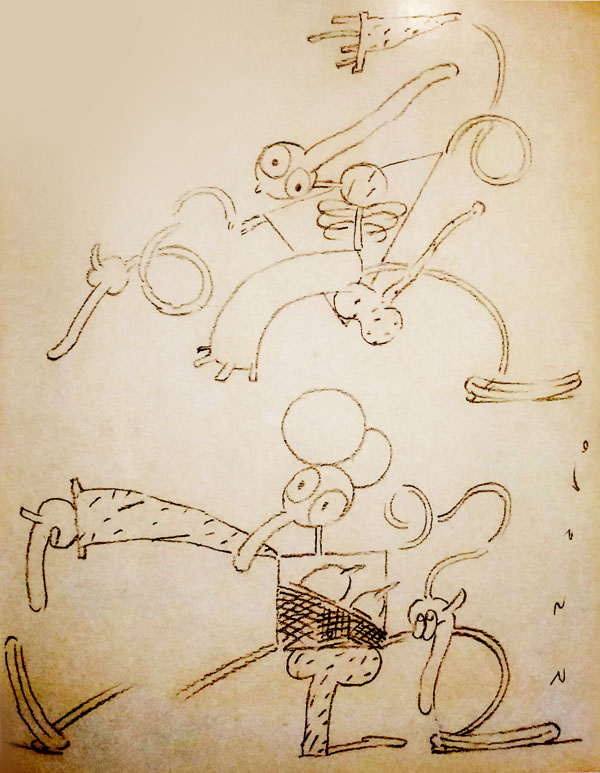

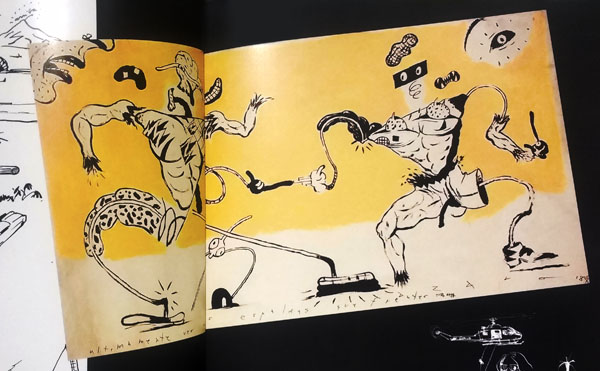

From Azaro’s catalogue

As it usually happens in these cases, two simultaneous approaches could be seen in the media: the articles aimed at the general public, insisting on his successes with Elton John and “The Wall”, and those written for the experts, lamenting the other reviews and insisting on Azaro’s legacy as a serious creator. This widespread confusion about one and the same person is the greatest tribute a genuine “pop” could dream of.

PART 2 of this article, covering artists Daniel Melgarejo and Patricio Bisso, will be posted next Monday.

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Thank you for this fascinating article. I guess it could be debated as to whether animated cartoons could be considered in some cases, high art, or just frivolous activity. I consider it the former, personally. I see this out loud, because I am sure there are people that consider cartoons clashing with the remainder of the art world. I don’t think this is necessarily, so, since sometimes our cartoons speak for us. As mentioned here, we have seen examples of the high art in classic cartoons, sometimes as sendup, and sometimes as great and inventive backdrop to whatever is going on in the foreground. I very much look forward to next weeks article.

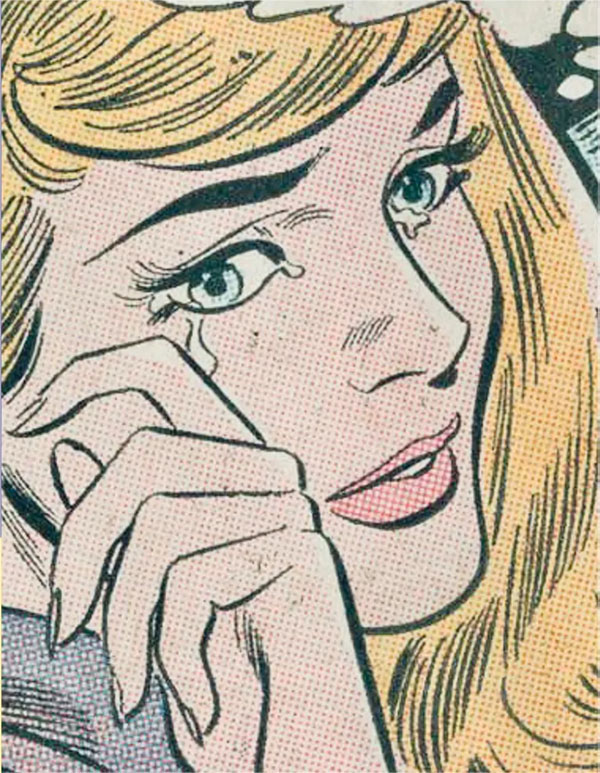

The Detroit Institute of Arts had a couple of Roy Lichtenstein paintings back when I was growing up there; it probably still has them. My mother, who like my grandfather was an artist, had nothing but contempt for Lichtenstein’s enlarged comic book panels of teary-eyed blondes, as well as Andy Warhol’s silk-screened Brillo boxes and pop art in general. Eventually my family avoided the modern art wing of the museum altogether so as not to upset her. To this day I can’t look at a Lichtenstein painting without thinking of my mother losing her temper.

I’m not surprised that Rodolfo Azaro’s work on Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” went uncredited. From what I recall of seeing the film back in 1982, it didn’t have any credits at all, either at the beginning or the end.

Animation, like filmmaking in general, is a collaborative enterprise, and someone like Azaro who “never quite fit in anywhere” was unlikely to have a long career in the field, even if he was capable of working in a variety of styles and media. Still, he left his mark on some notable works; the backgrounds in “Watership Down” are of exceptionally high quality. It sounds to me as if his life was far from “wasted”.

I know of at least one artist who “would lose his temper” by looking at Roy Lichtenstein’s body of “work” – ripping off some of his comic book artwork!

Noticing Azaro’s style, one wonders if Bill Plympton may have gleaned some influence from his work.

Some of Azaro’s work exhibited here reminded me of Elvis Costello & The Attractions’ music video for “Accidents Will Happen”, most of which is hand-drawn 2D animation. I just rewatched it on YouTube and, sure enough, the designs seem to resemble Azaro’s style. Does anyone here know which studio was responsible for that animation?

Snooty critics are the worst.