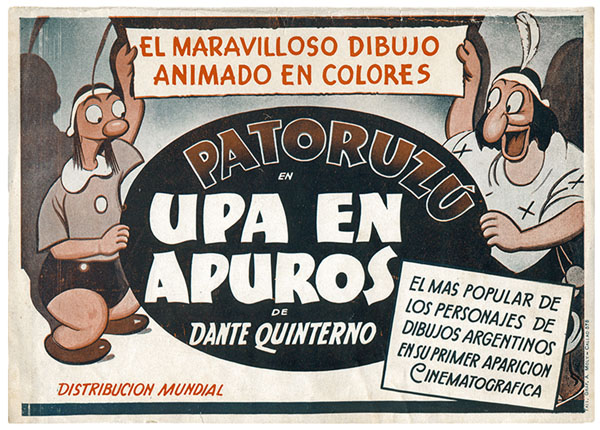

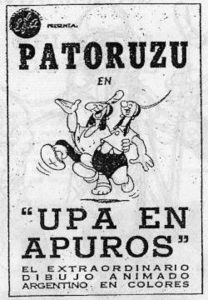

It’s a known fact that Upa en Apuros had an uneven luck, did not recover the initial investment and ended forever its author’s dreams of extending his domain to the movie screen. But who was Dante Quinterno? By 1942, the superstar of Argentine comics. His character “Patoruzú”, a Patagonian native of superhuman strength created in 1928 for a comic strip, had made him a national celebrity, to the point that when “Patoruzú” was featured in his own publication in 1936, the magazine was able to sell out a weekly circulation of 300,000 copies in a country then populated by less than 15 million people.

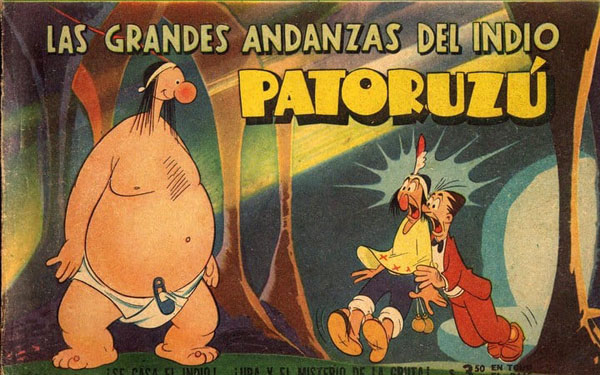

Patoruzu Magazine cover introducing the ‘Upa’ character

Quinterno had several elements that distinguished him from other Argentine artists who had ventured into the genre. To begin with, he was much more aware of U.S. production and commercial strategies than the rest of his colleagues. For example, the creation of the “Sindicato Dante Quinterno”, designed to commercialize both his creations and those of his collaborators in the magazine, followed the model of the American “syndicates”, an atypical practice in Argentine comics, where each cartoonist used to sell his material personally.

But there was another field in which Quinterno was interested.

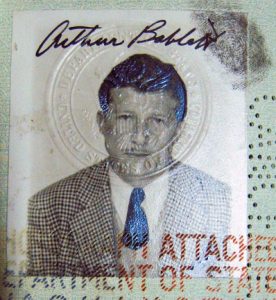

Dante Quinterno

There is not much information about Quinterno’s path in his Fleischer’s year; but the cartoonist Guillermo Mordillo (1932-2019) – who, at the beginning of the 1960s, worked at Famous Studios- once told me that the old animators of the company, such as Nick Tafuri and Seymour Kneitel, remembered fondly the other Argentine who had been there, “that Dante guy”.

The Italian historian Giannalberto Bendazzi, author of Twice the First: Quirino Cristiani and the Animated Feature Film (a book dedicated to Cristiani’s career, a pioneer who in 1917 produced in Argentina the first animated feature and in 1931 produced the first sound animated feature), goes so far as to state about Quinterno:

He came back with a project for a color feature film, with two American animators stolen from the Fleischers. That movie was the aforementioned “Upa en apuros”, for which he bought the machinery from his first teacher.

It’s a strange statement considering that I found no other source to substantiate it, that “Upa en Apuros” was produced around eight years after the trip and that there shouldn’t be many places to hide two Fleischer animators in Argentina, but anyway it helps to introduces that element of mistery that everything related to “Upa en Apuros” will have from now on.

According to Bendazzi:

The project was carefully prepared and well funded, but specific circumstances prevented him from making it into a feature because the film that he decided to use, Gasparcolor, was produced in Germany and WWII made exports impossible. Quinterno refigured the project, and made the idea into a 16 minute short film in 1942. It was very good, but, strangely, not accepted well by the public.

…which is not an inadequate summary, except on a couple of points that remain unexplained: the final short is just over 11 minutes long, the color film used is presented as “Alexcolor” (of uncertain existence) and that there are numerous divergent stories about what the project was intended to be in the first instance.

Some speak of a feature film; others of a medium-length film. All agree that the final short film is the result of the shortage of virgin material that affected the Argentine film industry during World War II (the raw film had to be imported from the USA, on whom the war economy had imposed restrictions). It is often added that the final German stock obtained had to be developed in Germany (in 1942!), which seems unlikely but cannot be ruled out.

Some speak of a feature film; others of a medium-length film. All agree that the final short film is the result of the shortage of virgin material that affected the Argentine film industry during World War II (the raw film had to be imported from the USA, on whom the war economy had imposed restrictions). It is often added that the final German stock obtained had to be developed in Germany (in 1942!), which seems unlikely but cannot be ruled out.

The production of Upa en Apuros began sometime in 1940 and the team was headed by Tulio Lovato as “animation director” (an artist considered by Quinterno as “his right hand”) and Oscar Blotta as “main collaborator”. It is not strange that they were the cartoonists in whom the Disney imprint had left its greatest marks: the whole short is influenced by that universe, with something of Popeye in the fight scenes. Below Lovato and Blotta was a group of no more than twenty people made up of collaborators of the Patoruzú magazine. None of them had done animation before (with the exception of Quinterno) so their ideas on the subject were rather intuitive. The Chilean Tito Davison – whose competence included dialogues and editing-, the Dutch musician Melle Weersma and the German artist Gustavo Goldschmidt completed the technical staff.

And this was all the material available on the subject until the historian Jake Friedman, author of a book in preparation on the animator Art Babbitt (1907-1992) made Babbitt’s diaries available to the readers of his “babbittblog”.

And this was all the material available on the subject until the historian Jake Friedman, author of a book in preparation on the animator Art Babbitt (1907-1992) made Babbitt’s diaries available to the readers of his “babbittblog”.

It is useless to introduce Arthur Babbitt to the readers of Cartoon Research, or to recall his role in 1941 as one of the leaders of the iconic Disney strike. The move, which Walt later blamed on “communist agitators,” triggered enmity between the two men, to the point that, according to one version, only the intervention of his colleagues prevented them from ending up in a fistfight. By then, the affair had turned into a quarrel that included pickets of animators parading outside the company’s gates, alleged mafia groups, media campaigns against both contenders and the support of staff from other animation studios for the strikers.

An unexpected source of information on the subject is the biography of Disney written by his daughter Diane in 1957 with the collaboration of Pete Martin, a rather candid material, but which in its simplicity provides some interesting details:

While the strike was at fever pitch, the Government sent a man to Dad with a request. Would he tour South America as a sort of good-will ambassador? The plea was made on behalf of Nelson Rockefeller, the State Department’s Co-ordinator of Inter-American Affairs. “Your pictures are popular down there,” Dad was told, “and there’s a Nazi influence which you can help offset. It would be nice if you’d go down there and meet people” (…) There was one hitch: the strike was still going on. But a Government official told Dad, ‘We’ll take care of it while you’re gone. We’ll have the labor board get the warring factions together and settle things. You can quit worrying.”

Walt Disney and Dante Quinterno in 1941

The trip followed the regulations of Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy” implemented through the Rockefeller Commission. Disney and a small group of “loyal” artists fulfilled their role to perfection. In Argentina they gave interviews and lectures, met with Quinterno and Quirino Cristiani and took along the artist Molina Campos (a specialist in gauchos who was later pondered by Jack Kinney only because he tended to draw his backgrounds with a low horizon, leaving a lot of sky on top, which was good for “reading” the animated characters). Back in the USA, Disney made a film about the experience (Saludos Amigos) that integrated documentary footage with animated episodes.

A few months later, his nemesis arrived in Buenos Aires. It was none other than Art Babbitt. But Babbitt brought a personal diary where he wrote down everything.

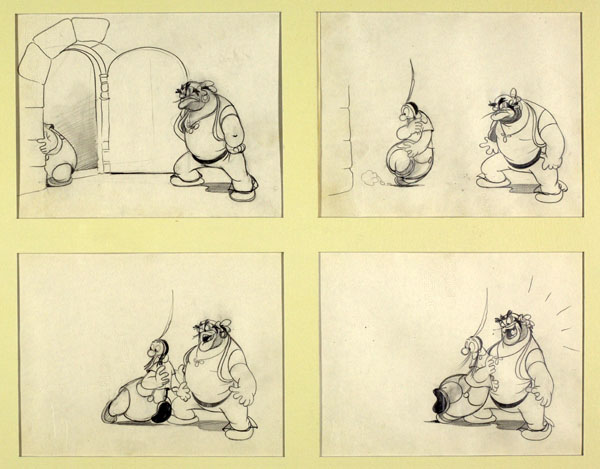

“Upa” storyboards drawn by Quinterno

Excerpts from Art Babbitt’s diary:

February 6, 1942

[…]Dante Quinterno and his production head – Tullio (NOTE: It’s Tulio Lovato, the main artist of Quinterno) met me at the boat. Dante seems to be a big shot here – because the chief of the customs house came over personally to supposedly check my baggage. He simply opened and closed my cases, never bothering to look at anything – then motioned me on.

Being terribly tired – I was entertained but briefly – then send to bed. The apartment Dante + Tullio found for me is a beauty in the heart of the business district – very “moderne”.

February 7, 1942

Spent practically all day at Quinterno’s place. I don’t know where he gets all the energy — but he most certainly has his finger in plenty of pies. He has thirty employees – and besides his newspaper comic strip he edits and publishes a humorous magazine – does three additional comic strips and is producing an animated cartoon.

I heard their sound and saw the pencil tests of their picture today. The music is exquisite – the characterization very good and the plot and gags good but a bit heavy and brutal in a typically foreign manner. The animation is not too good — but considering the fact that these men have taught themselves all the principals of animation in but a few months — their work is remarkable.

Some of their actions are exceedingly original – humorous and refreshing and both Tullio + Dante are damn good draftsmen. Their equipment is primitive – but still a hell of a lot better than I had expected.

February 9, 1942:

Spent all day correcting the animation and story of Dante’s picture. It was hard work but i enjoyed it thoroughly. Who knows – I may be in some sort of partnership in time to come. I think I’ll wait to see what sort of success he has with his first picture and then it might be a good idea to make a tie-up.

Dante is a man of temperament – but he has good judgement and taste. He’s not the boor that Disney is. […]

With the shortage of Spanish at my disposal – it was quite an adventure to buy a roll of toilette paper today.

The Argentinians do not like Americans and they want no part of this war.

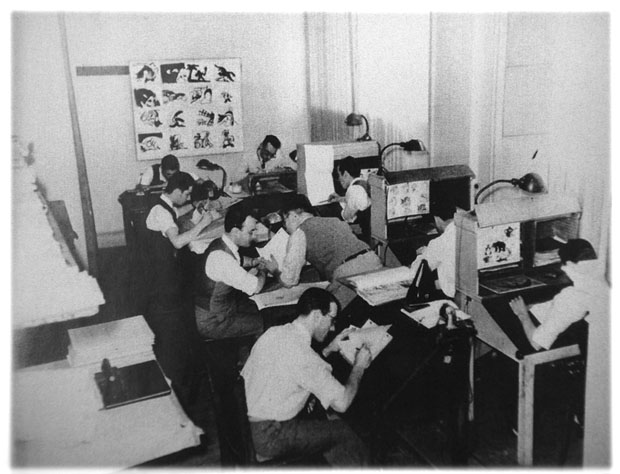

Quinterno Studios during production of “Upa en Apuros”

February 10, 1942:

Worked all day with Tullio Lovato. He speaks no English at all… so it was a wonderful experience to understand and make myself understood with my meagre vocabulary and lack of construction knowledge. My dictionary was in constant use […]

We had an excellent dinner – danced with the lovelies furnished by the nite-club – the “Bal Tabaris”. Then walked a few blocks to the opposite extreme in night clubs. We had to show our passports to get in. There are at least ten plain clothes men on duty constantly and every woman in the place is a whore. A real dive – but damn good music.

February 28, 1942:

Quinterno was so anxious to get back that he drove from Mar del Plata at 140 kilometers per hour and arrived early this morning.

I went over the continuity of his pictures with him — arranging for cuts and shifting of sequences to tie the story together.

He made it clear that he would give me a partnership in his business if I’d come on down.

[…]

March 2, 1942:

[…] Dante made a very flattering offer- and should my business in the states permit me to do so – I may come back to Argentina in about 6 months and plan to stay about 2 years.

March 9, 1942:

[…] Just recalling the South Americano reaction to some of our good-will ambassadors – I found that Bing Crosby was constantly drunk and surely to newspaper men and haunted the whore-houses. Tyrone Power picked his nose as he walked on crowded Avenida Florida in B.A. Stokowski was a flop and his supposed temperament angered the people of Montevideo. Douglas Fairbanks Jr. + Lily Pons were disliked – but Disney, Toscanini and Clark Gable were popular.

However, Disney made a terrible faux pas in Argentina. In his smart alecky way – he was dressed in a “gaucho” costume when he was invited to a home of a very aristocratic family. The hosts stood by and watched his antics but were so annoyed they didn’t even sit down to eat with Disney. […]

But a particularly interesting point is found in the March 3 entry:

[…] I checked with Ray Josheps of the Rockefeller Committees in Argentina and he thinks we might get some help in our release arrangements. Through Nelson Rockefeller and Jock Whitney. At any rate there’s much to think about in the next few months.

Friedman is not sure of the handwritten name in the diary, and transcribes it as “Josipho”, but there is no doubt that Babbitt is referring to Ray Josephs, the RKO representative for Latin America. At the time, Josephs was also a correspondent for the American newspaper PM, where Quinterno published an English translated version of Patoruzú from 1941 to 1948. As the Committee’s local contact, Josephs had previously arranged Orson Welles’ Brazilian tour and other similar trips. His name would be mentioned again in 1944, this time as the author of the book “Argentine Diary”, a book written to anathematize the political course of Argentina in those years.

What is interesting in this story is that Babbitt, the “agitator”, fulfilled a path so similar to that of Disney. Argentine cartoonist Oscar Grillo confirms this point, adding a strange nuance:

About the seventies I met the great Disney animator Art Babbitt, Quinterno had told me he had been a consultant in the movie and I confirmed this but added that he had been sent by the State Department to investigate U.S. Nazi penetration culture in Argentina (his words).

It should be recalled that the strike had justified the State Department’s entry into the studio, with the “we’ll take care of everything” that managed to bring the not very controllable Disney in line. At the time, Disney could still be seen as a representative of an “old-fashioned” way of understanding private enterprise, which resisted share sales, board meetings or other forms of corporate management.

Snow White was called “Disney’s folly,” or at least it was until it brought in a lot of dough; and the same was thought of the triad of Bambi, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, which made it go just as easily. The new business model imposed by the Second War was to change all this. On December 8th, 1941, a day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Disney Studio dawned occupied by the Army. Walt was to spend the rest of the war producing mostly propaganda material for a single client and it is likely that, with world markets volatilized by the war, he would be grateful. It is precisely at this time that Babbitt is sent to Argentina.

Snow White was called “Disney’s folly,” or at least it was until it brought in a lot of dough; and the same was thought of the triad of Bambi, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, which made it go just as easily. The new business model imposed by the Second War was to change all this. On December 8th, 1941, a day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Disney Studio dawned occupied by the Army. Walt was to spend the rest of the war producing mostly propaganda material for a single client and it is likely that, with world markets volatilized by the war, he would be grateful. It is precisely at this time that Babbitt is sent to Argentina.

A plausible conjecture is that Josephs served as a bridge between Quinterno and Babbitt, and then the Rockefeller commission gave the green light to this adventure: Quinterno’s interest in the animator coincided with the need to get him out of the way. It’s needless to warn that here we move in the field of hypothesis, but the fact that Babbitt believed in Quinterno’s project seems to be proved in his notes about the possibility of settling in Argentina; while the absence of his name in the credits of the short film is logical if we think that at that time the cartoonist still considered himself a Disney employee. The Rockefeller mission could be a way of adding some “official score”, something necessary after the weak position he had been left in after the strike.

However, Upa en Apuros did not work well, and perhaps the problem was precisely Disney’s influence, which placed the character in some abstract cartoonland, when the success of the strip had been linked to a concrete place.

You can evaluate the final result here:

In any case, Art Babbitt returned to the United States, never to return to Argentina. Freed from his contractual burdens, he played an important role in the company that led the next great transformation of American animation. Coincidentally, the name of that company was… UPA.

The author of this post and the editor of this blog would like to thank Jake Friedman for his research on Art Babbitt – and highly recommend all readers buy Friedman’s new book, The Disney Revolt, for further information on Babbit.

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

That’s quite a good cartoon, reminiscent of the Fleischer product during the studio’s final years, though it would have needed some additional characters if it had been made as a feature. The villain reminds me of Dirty Bill from the Disney Silly Symphony “The Robber Kitten”.

I was very interested to see Babbitt’s comment about the angry reception Leopold Stokowski received in Montevideo; there must have been a lot of talk about the incident. What happened was, some incorrect biographical information about Stokowski had been printed in the concert programs, and he refused to start the concert until the ushers had taken back every single program from every member of the audience. It’s no surprise that Toscanini was popular, as his first successes as a conductor had taken place in Brazil and Argentina over 50 years earlier, and he had long been a revered figure among music lovers in those countries. Stokowski believed that Toscanini’s South American goodwill tour had been deliberately scheduled immediately prior to his own in order to make him, Stokowski, look bad, and he took it as a personal insult. But NBC had already scheduled Toscanini’s tour before they even knew that Stokowski would be making one. Besides, Toscanini was touring with one of the world’s finest professional symphony orchestras, whereas Stokowski was traveling with the All-American Youth Orchestra; and while I’m sure those kids were very talented, they simply weren’t in the same league.

The Argentine model Yesica Toscanini is no relation to the maestro.

This is a fascinating account, and I’d like to read more about the history of animation in Argentina and other countries.

Cool cartoon, and what a great story. Thanks, Lucas!

These unknown-to-me historical overviews keep getting better and better.

The cartoon production was amazing, especially given the back story. But one plot bit puzzled me. Why was Upa seen as money by the bad guy? Was it something as simple as kidnapping for ransom?

The Upa > UPA conclusion was amazing. The kind of thing that can only happen in Toontown!

The wanted poster bills the bad guy as “Ladron de Ninos”, basically “Thief of Children.” I think you’re right that ransom is the end goal.

According to the dialogue, he was going to sell Upa to the circus.

The reason the villain sees Upa as a ripe prospect for ransom is because Patoruzu is actually a fantastically wealthy tribal chieftain with land holdings in Patagonia. Like Scrooge McDuck’s wealth, it’s actually a driving point for most of Patoruzu’s adventures, making him (and his family, obviously) a target for villains or a fall guy for his greedy city friend and sometimes fight manager Isidoro. The cartoon would have been made with the general expectation that Argentinian audiences would already be well familiar with the strip’s tropes. It’s a shame that, apart from a brief and ill-fated attempt at syndicating Patoruzu through New York’s PM newspaper in 1941, Quinterno’s frankly terrific work hasn’t been translated into English. Patoruzu is a great strip.

Thanks for the clarifications, guys!

The origin of UPA as an brand name always was murky. After all, it was still FMPU when this cartoon was made, and “United Productions of America” sounds completely arbitrary, so it would explain a lot.

Fascinating backstory, thanks so much for sharing

For a cartoon made with a lot of green talent, it certainly is assured in spite of some rough patches. Compared to the UK produced Bubble and Squeek efforts (another studio trying to start a working operation from scratch), it is very well designed and paced, and some of the action sequences would have passed muster at Fleischer’s. There’s a brief shot of the kidnaper, acting as a magician, where you’re looking up at him while his hand is moving toward and away from the camera in a hocus-pocus gesture that is especially sinister.

The first time I saw it, I was kind of confused because the child Upa is as big as his pop, but now I get it. I’m surprised it flopped, the characters being so popular, but I don’t know the comic it was based on so perhaps the film strayed too far from what the audience expected.

Interestingly, I found a different YouTube version of this film where the soundtrack has been completely replaced by a synthesized one. Maybe because the original seems to have a pronounced flutter.