Note: Due to its length, this article is divided into three parts. Its purpose is to study the development of animated films in a place and a period not always well documented, a problem that lies not so much in the lack of historians as in the lack of documents. Starting with the films themselves.

Part One

Introduction

When the Italian historian Giannalberto Bendazzi set out on the trail of Quirino Cristiani, not much information was circulating on the subject: only the unlikely promise that in a distant southern country an Italian immigrant had directed the first animated feature film ever made and, not happy with that, a few years later he had produced the first one with sound; a fact that, however, did not appear in any of the many histories of cinema that had been written up to that time. Bendazzi found in Cristiani the gold vein he had come looking for and his book changed everything that was thought to be known about the subject until then. In it, the historian did not fail to express his perplexity that a public and notorious fact had gone unnoticed for so long, even by the Argentines themselves, who did not seem to understand the importance of such a milestone.

Bendazzi was half right. It’s true that after him, cinema scholars began to state that El apóstol, by Quirino Cristiani, was the first animated feature film, dated 1917 and therefore nine years prior to The Adventures of Prince Achmed, by the German Lotte Reiniger (which came to be considered the second). The problem is that this idea, while cute, was slightly false. Argentina had not produced the first animated feature, as the historian claimed, but – most probably – the first four.

The problem with Bendazzi’s approach is a common one when it comes to writing Film History: personal biography is not enough to account for a collective enterprise. In the story of the first animated feature films there were several actors involved, and Cristiani (the last survivor of the original venture) was only one of them. We can narrow these players down to three main figures: Cristiani, producer Federico Valle, and (perhaps the most mysterious of all) director and animator Andrés Ducaud.

Because despite the fact that Cristiani seems often to be the only one on board in his version, he appears much less in the one that Federico Valle, the producer of El apóstol, gave to journalist and historian Domingo Di Núbila in the 1940s and served as the basis for the book Cuando el cine era aventura (When cinema was an adventure). And if Di Núbila dedicates an entire book to Valle, it is not in a display of generosity: Valle is the first in everything, he’s there before anyone else, he did it when the others were just thinking about it.

So let’s begin this story with Federico Valle, producer (and inventor) of El apóstol.

Image 1- Federico Valle, circa 1920s.

1- Federico Valle, Super Genius

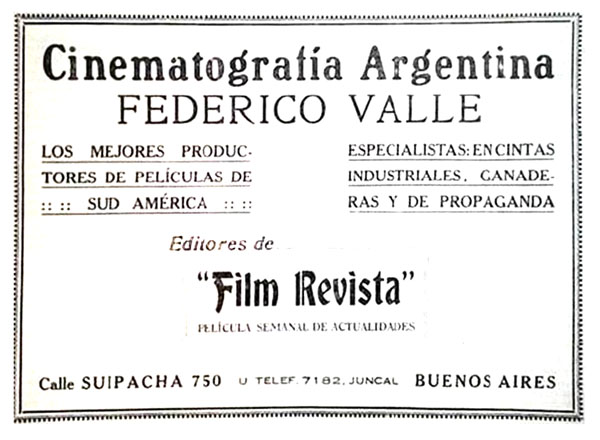

Federico Valle was born in 1880 in Asti, Italy. Relocated to Paris in 1904, he found employment as “Spanish and Italian correspondent” in the French branch of the “Urban”. The “Charles Urban Trading Company” was an English film company specialized in travel, educational and scientific films, shooting all over the world (for example, it had a correspondent in Russia and another in Japan to cover both fronts of the Russo-Japanese war). In Urban, Valle was first in charge of the commercial correspondence, sales and rentals.

Soon, Valle became familiar with all aspects of the company at a time when production, distribution and exhibition were three phases of the same operation. There he met the Lumière brothers and crossed paths with Georges Meliès, a regular customer of the company, whom he visited several times in his studio in Montreuil. A couple of years later, one of the members of the Urban (George Rogers) went on his own to found the “Société Générale des Cinématographes Éclipse”, which would end up being one of the most important production companies of the pre-war period.

Soon, Valle became familiar with all aspects of the company at a time when production, distribution and exhibition were three phases of the same operation. There he met the Lumière brothers and crossed paths with Georges Meliès, a regular customer of the company, whom he visited several times in his studio in Montreuil. A couple of years later, one of the members of the Urban (George Rogers) went on his own to found the “Société Générale des Cinématographes Éclipse”, which would end up being one of the most important production companies of the pre-war period.

Rogers took Valle with him, but the latter set as condition to being employed as “camera operator”. Félix Mesguich (one of the Lumière cameramen) taught him the technique.

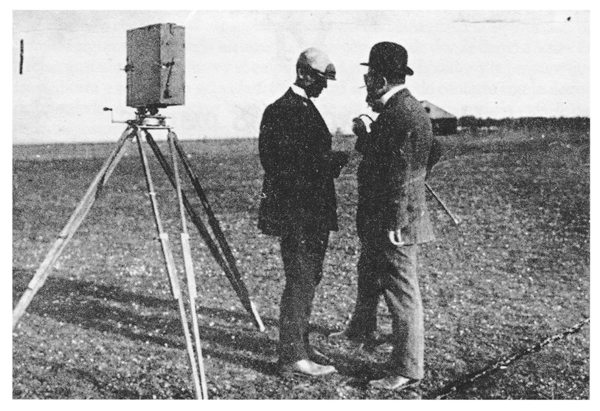

That’s why in 1909 Valle managed to fly on the Wright Brothers’ plane (upon a board tied with wire: it seems that a passenger seat was about to be invented), and get the first aerial movie shot filmed from a heavier-than-air aircraft in the field of Centocelle, near Rome.

Wilbur Wright and Federico Valle

According to Valle’s memoirs, Orville Wright served as the duo’s PR, but the key figure was the taciturn Wilbur, whom the operator managed to win over thanks to his discreet way of working (Mesguich would also shoot another aerial shot in the Wrights’ plane, somewhat later, filmed in Pau, France).

First aerial shot recorded by Federico Valle, at Centocelle (1909).

As cameraman of Eclipse, Valle filmed from the rescue efforts after the earthquake in Messina, Italy, to the elusive Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II (discovering in the process the advantages of the hidden camera) and even traveled to South America, whose only reference until then had been the partridge hunts of Mr. Valle (senior), who had been living in Argentina for years. It seems that, along with the partridges, Valle smelled the opportunities that could offer him a country where an entire industry was waiting to be developed. By 1911 he was already installed in Buenos Aires as a representative or distributor of several European companies, and equipped with his own laboratory, designed to translate and copy the films that were arriving from abroad.

But Valle had an invincible taste for adventure and found the exhibition business irresistible. Mar del Plata was then the fashionable seaside resort, a city located on the sea 400 kilometers south from Buenos Aires. Valle rented one of the two existing movie theaters on the so-called Rambla Francesa (French Promenade), an architectural jewel of Art Nouveau.

Image 5- French Promenade in Mar del Plata.

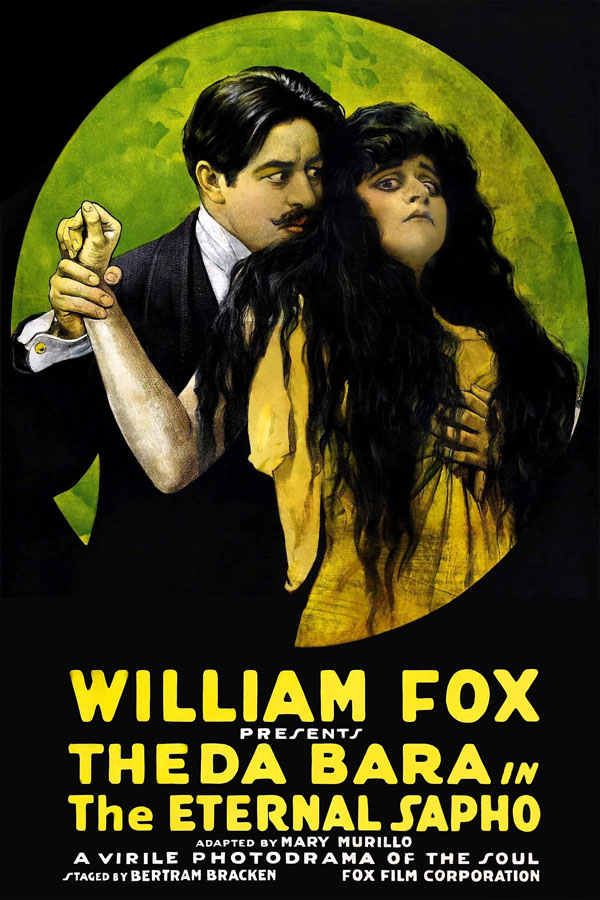

His rival was Max Glücksmann, the big producer/exhibitor of the moment, but Valle had the novel idea of not closing in winter. He discovered that the local people of Mar del Plata was enough to fill a movie theater. Encouraged, he bought around 1915 his own place, which he christened “Regina Palace”. He had to equip it from scratch, and for that he contacted Andrés (or André) Ducaud, a Frenchman “of astonishing manual ability”, who had arrived to the city with the engineering company that had built the promenade. Ducaud was an architect and draftsman of “an intelligence and technical mastery that knew no boundaries: he understood mechanics and electricity, and had even made stylish furniture” and would later become a key figure in this story. Together with Valle, they put the finishing touches to the venture and on the opening night they literally left their audience glued to their seats: the varnish they had used was slow to dry. The disaster seemed absolute, but Valle had a plan. With a last-minute loan, he managed to launch his “Red Fridays,” which included films by Theda Bara and other Fox vamps, hitherto spurned by Argentine distributors.

Theda Bara poster around the year Valle started his “Red Fridays”

The programs were printed exclusively in red ink (a color linked to brothels in the collective imagination) and the posters, “instead of normally being pasted up, were fixed horizontally on the walls, so that at first glance one had the sensation that the apollonian George Walsh was on top of the lady he was passionately kissing.” Seats booked by telephone, high lapels and wide brimmed hats completed the atmosphere of confidentiality. Valle saved his investment and was able to move on. He brought the ingenious Ducaud to Buenos Aires, because he already had another project in mind. Having taken a step in the exhibition, the next thing was production. He had to assemble (“create” is a better term) a team of technicians to produce films “industrially”. He needed writers, cameramen, draftsmen. “Cinematográfica Valle” was born.

Valle’s initiatives advanced on multiple fronts simultaneously. In all cases, they shared some degree of the creative improvisation that proved to be central to his triumphs and key to the final defeat. Because Valle depended to a large extent on the team he had formed, people who came and went, at times founding rival companies that lasted as long as it took them to return home. The mechanics of production, according to Valle’s account to Di Núbila, was quite simple: Valle has an idea and throws it to his boys. The initiative belongs to the first one who is able to develop it.

Another notable characteristic of Valle as businessman seems to have been his ability to ride his own intuitions on the back of outside investors. The main line of work was, of course, advertising and institutional films, of which Valle produced an estimated four hundred titles, including industrial and commercial documentaries made for different companies and government agencies, which could be exemplified in this short film commissioned by the newspaper “La Nación”.

Cinematográfica Valle, “La película del gran diario de la Argentina” (“The film of the great newspaper of Argentina”), 1930.

Starring the Spanish actress Vina Velázquez and the actor Alfredo Zorrilla (who would later pursue his career in France), it became a field of experimentation for the producer, who summed up in the movie what we could call the keys to his style: to take advantage of the concrete offer of an external client to develop a filmic work that sometimes bore a slight resemblance to what was requested, to use and reuse existing material as much as possible, and a certain distrust (natural in a documentary filmmaker) of professional actors and stage sets. Valle tested in his productions the common people he met in the streets, and he also tested the streets. For example, while filming El Ovillo…, he discovered a certain woman working in a drugstore that he considered perfect for the role of the second star. Finally, his scriptwriters had to retire the character to a convent when the pharmacist, furious after several days of shooting, came to take his wife home.

Starring the Spanish actress Vina Velázquez and the actor Alfredo Zorrilla (who would later pursue his career in France), it became a field of experimentation for the producer, who summed up in the movie what we could call the keys to his style: to take advantage of the concrete offer of an external client to develop a filmic work that sometimes bore a slight resemblance to what was requested, to use and reuse existing material as much as possible, and a certain distrust (natural in a documentary filmmaker) of professional actors and stage sets. Valle tested in his productions the common people he met in the streets, and he also tested the streets. For example, while filming El Ovillo…, he discovered a certain woman working in a drugstore that he considered perfect for the role of the second star. Finally, his scriptwriters had to retire the character to a convent when the pharmacist, furious after several days of shooting, came to take his wife home.

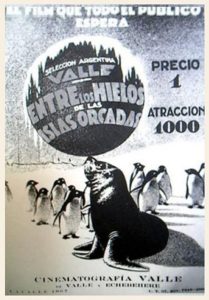

And if it is true that Valle often preferred real locations over sets, it is fairer to say that the producer seems to have considered the whole of Argentina as a formidable open-air stage. He conceived documentaries from various regions of the country, shooting some personally or sending his cameramen to places that included the far-flung Orkney Islands.

“Entre los hielos de las Islas Orcadas” (“Among the ice of the Orkney Islands”, 1928), was filmed by the Argentine meteorologist Juan Manuel Moneta twice, because the first version was destroyed in the fire at the Valle Studios in 1926. It is said that Moneta, upon hearing about it, laconically exclaimed “Another year in Orkney!” and set off for the islands again.

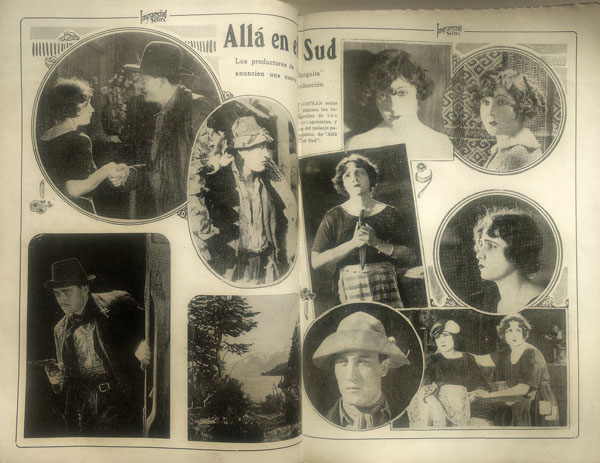

Valle also imagined an entire genre, which we could call “Patagonian western” for lack of a better name (“southern” would be more correct), and in 1921-22 he sent his crew to southern Argentina to shoot not one but three films at the same time: Patagonia, Allá en el Sud and Jangada Florida, directed by his main cameraman, Arnold Etchebehere, and starring actors Nelo Cosimi and Arauco Radal along with actresses Amelia Mirel and Raquel Garín.

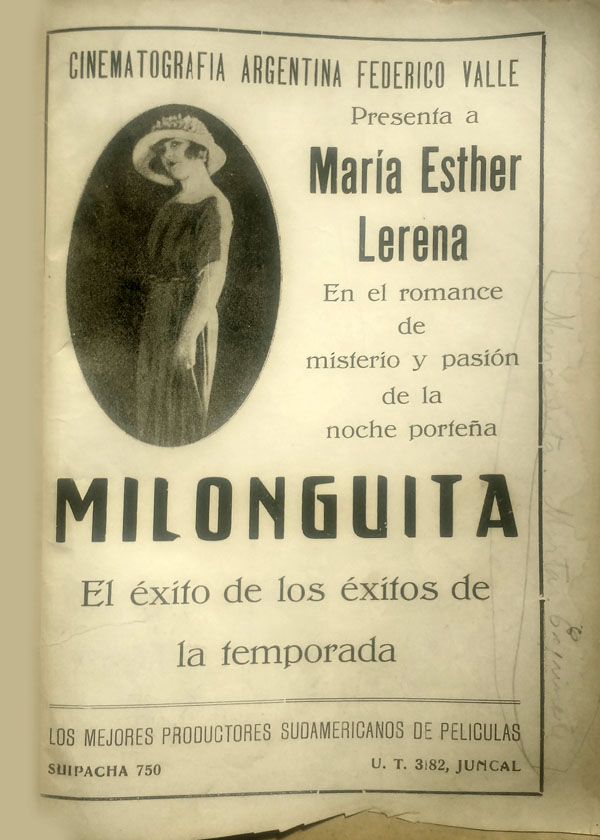

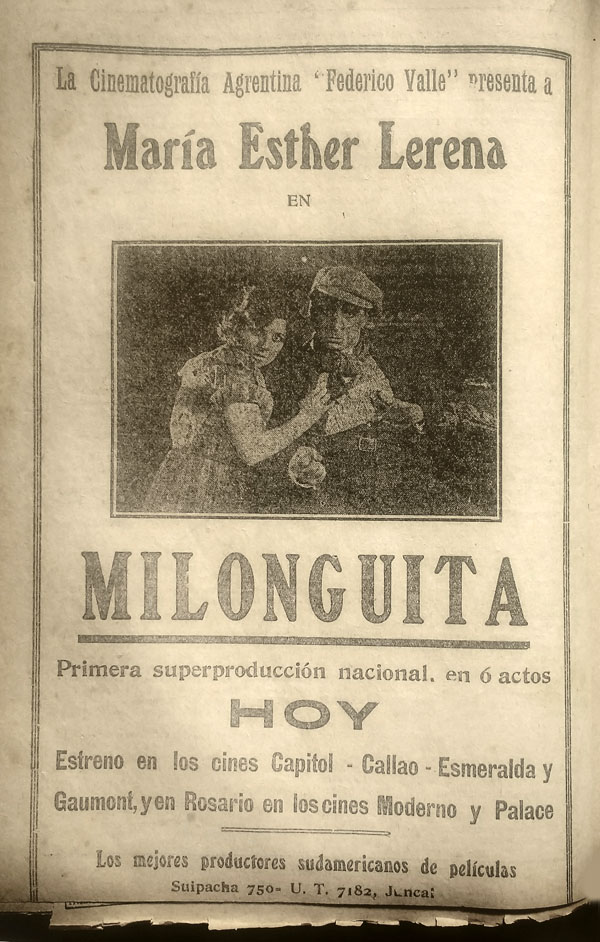

Several feature films followed the Ovillo’s path, as Milonguita, a huge hit of 1922, this time with the sophisticated Bustamante in the direction, at the expense of a well-known tango by Enrique Delfino about the typical girl who goes downhill.

Milonguita flyer in Cine Imperio

El Toro salvaje de las Pampas (1924), directed by Italian director Carlo Campogalliani from a book by Bustamante, took advantage of the enormous popularity of Argentine boxer Luis Ángel Firpo after the legendary fight in which he punched world champion Jack Dempsey out of the ring, in a melodramatic plot that, nevertheless, followed the “Valle’s dogma” by including documentary fights in its footage. From the same Campogalliani, Valle produced La mujer de medianoche (1925). Adiós Argentina (1930) was directed by another Italian, Mario Parpagnoli, in a co-production with Brazil, which, as a curiosity, included the musical pentagram at the bottom of the frame so that the orchestra could play the corresponding music by reading the score. An additional sign of Valle’s wit, considering that among the things the producer boasted of having invented -or reinvented- were already the following:

-The (South American) weekly newsreel. Film Revista Valle, presented itself since 1916 as “a weekly film of Argentine news, the first of its kind published in South America. A unique act. Synthesis of the Argentine dynamism, mirror of its beauties”. It will last until the advent of sound, completing 657 editions. This synthesis of Argentine dynamism was, however, the fruit of the multiple talents of the Peruvian Bustamante y Ballivián and, above all, Valle’s incredible cameramen, who seem to have achieved miracles in the art of catching the news on the fly. After Bustamante’s departure, Valle briefly tried a young writer as a replacement, but with no luck. It was Jorge Luis Borges.

Documentary excerpts filmed for Film Revista Valle.

-Something that today we might call a “video clip”. Around 1930, Valle hired the international tango star Carlos Gardel, along with his guitarists, to make a series of shorts (with optical sound) directed by Eduardo Morera, in which Gardel sang a tango; sometimes accompanied by a brief story where the star interacts with the authors of the songs. Almost all this material is still preserved.

Compilation produced after Gardel’s death in 1935, which sums up all the shorts produced by Valle in a single film.

-The subtitles in transparency at the bottom of the image, which Valle claims to have created due to the need to translate the first spoken English-language sound films and which “a Fox representative in Argentina took note of”.

-And, of course, the animated feature, which is what I guess you’re waiting for. But let’s leave this for the next installment – next week. We’ll have Valle for a while.

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Federico Valle… his last production is from 1934. They say his nitrate archive became hair combs. Several of his films surfaced and have been digitized. He mostly produced institutional films, promoting commercial companies, sport clubs, and events that in certain cases, including documentaries, surfaced and are in YouTube. He filmed himself the events of the military coup on September 6, 1930, and his last production is from 1934.

I never believed the story that his nitrate collection became hair combs even if it is still repeated; in fact his company suffered several fires throughout the years (anybody can find the photos of the 1927 that burned his offices in downtown Buenos Aires).

I’ve read that for a while in the early twentieth century, Argentina had a stronger economy than even the United States. Many European concert artists and opera singers considered Buenos Aires a better venue than New York, with better pay and better audiences. So it’s no wonder that Federico Valle found it a propitious place to establish a film industry. The cinematography in these films is very good, with a lot of arty touches like double exposure and split screens. I have a feeling, though, that Valle’s attitude of “anyplace can be a movie set, and anyone can be an actor” might have worked against him in the long run.

The documentary on the South Orkney Islands was very interesting, though the butchery of the whale and the seal is likely to put off viewers today. I was intrigued to learn that the Spanish name for Cape Horn is “Cabo de Hornos”. Doesn’t that mean “cape of ovens”?

I’ve long been interested in Quirino Cristiani and his lost animated films, so I’m really looking forward to Part Two!

Federico Valle… his last production is from 1934. I never believed that his nitrate archive became hair combs. Several of his films surfaced and have been digitized. He mostly produced institutional films, promoting commercial companies, sport clubs, and events that in certain cases, including documentaries, surfaced and are in YouTube. He filmed himself the events of the military coup on September 6, 1930, and his last production is from 1934. I never believed the story that his nitrate collection became hair combs even if it is still repeated; in fact his company suffered several fires throughout the years (anybody can find the photos of the 1927 that burned his offices in downtown Buenos Aires).