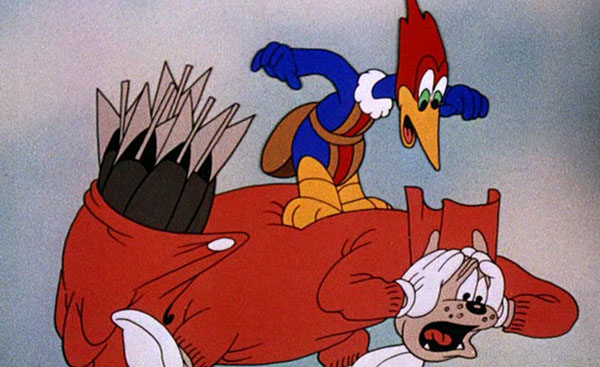

The Air Force sergeant clings to the underside of the plane and yells, “Open up, lemme in.” And in short order, from the cockpit, Woody Woodpecker releases bombs from a dropchute that fill up Sarge’s pants. He grumbles, “Why you red-headed little…” but then cuts short his profanity. Woody has been domineered by the sergeant for most of Ace in the Hole and now the tables have turned. When we hear the crazy bird laugh, “HahahaHAAAhaa,” we know this guy’s got it coming.

The Air Force sergeant clings to the underside of the plane and yells, “Open up, lemme in.” And in short order, from the cockpit, Woody Woodpecker releases bombs from a dropchute that fill up Sarge’s pants. He grumbles, “Why you red-headed little…” but then cuts short his profanity. Woody has been domineered by the sergeant for most of Ace in the Hole and now the tables have turned. When we hear the crazy bird laugh, “HahahaHAAAhaa,” we know this guy’s got it coming.

In concluding these posts on the first-ever study of cartoon violence, we need only look at the original published report to reveal a last surprise: by a slim margin, the data showed the opposite of what is typically reported today. In this now-famous 1955 psychology experiment, children were shown Ace in the Hole and also The Little Red Hen. Here’s a sentence about it from a May 1997 article in The Atlantic Monthly: “The Woody watchers were much more likely than the Hen watchers to hit other children, break toys, and be generally destructive during playtime.”

In fact, this really was not the case. As I mentioned last month, the researcher Alberta Siegel set up toys for the kids to play with after they had watched each cartoon. These included not just a doll and tea set, but also a punching bag and two rubber daggers. Perhaps because it strikes people as a reasonably likely result, no one has challenged this narrative that kids watched Woody Woodpecker and then “were more likely to hit other children” as a result—or to jab them with conveniently available rubber knives?

When Alex Lovy directed Ace in the Hole in 1942, America had just entered WWII and the country was increasingly militarized. Setting a Woody cartoon inside of an Air Force base was a way to show patriotism and also to offer some comic relief amid the rising American resolve. Cartoons did their part by lightening the mood for just a moment. Even shortly after he directed this film, Lovy was drafted into the Navy and had to leave the Lantz studio to begin his service to the war effort.

When Alex Lovy directed Ace in the Hole in 1942, America had just entered WWII and the country was increasingly militarized. Setting a Woody cartoon inside of an Air Force base was a way to show patriotism and also to offer some comic relief amid the rising American resolve. Cartoons did their part by lightening the mood for just a moment. Even shortly after he directed this film, Lovy was drafted into the Navy and had to leave the Lantz studio to begin his service to the war effort.

More than a decade later, Siegel chose this film in large part because a Child Development supervisor had approved it for her to show. With that permission obtained, 24 children attending a nursery school in State College, Pennsylvania were allowed to take part in this study. Ace in the Hole was considered the Experiment (the film shown to “the E group”) and The Little Red Hen was the Control (for “the C group”). The kids were shown both films separately and then they were observed for a 14 minute period just afterward to see if there was an effect.

All 24 children were scored by Siegel and her assistant Ellen Tessman to gauge their level of aggression and their level of anxiety and guilt. According to Siegel’s report, they “observed the play of each child for behavior which might be termed ‘hostile,’ ‘destructive,’ or ‘aggressive.’ Such behavior might be toward the other child, toward a toy, or toward the self.” Additionally, the aggression was rated by intensity, on a scale of 1, 2 or 3, with a score given every 20 seconds.

Siegel noted with satisfaction that the two scorers, she and Tessman, were “in unusually high agreement,” providing “a Pearson correlation coefficient” of 97%. As for the guilt and anxiety index, their reliabilty was 77%. Siegel ruled that the guilty and anxious behavior displayed less frequently than aggressive behavior, making it harder to score. These results were then compared with the observations of the teacher back at the nursery school to offer an additional check and balance.

To conclude the report, there were two hypotheses being examined. Here’s the first of two findings: “Somewhat more aggression occurred in the E than the C sessions, but the difference was not significant.” That means that watching Woody stuff a guy’s pants with bombs only made the kids slightly more likely to play rough. And more startling was this for the second hypothesis: “Somewhat more anxiety and guilt occurred in the E sessions (i.e., the difference was in the opposite direction from that predicted), but… the difference is insignificant.”

Let’s break that down for a moment. Siegel considered anxious/guilty behavior to include expressions of self-restraint, reproachment, and even “awkward moments.” She had expected that showing kids a gently moralistic cartoon like The Little Red Hen would make them play more considerately. Instead, by a slim margin, the opposite was true. The more violent conflict of Woody fighting with an Air Force sergeant made the kids subsequently show more restraint and remorse.

This is interesting because Dr. Siegel was hoping to dispute the prevalent notion, in its time, that media violence was cathartic to viewers. In her own report, the data was leaning slightly toward upholding that view. Here again are her comparative findings:

1. Kids prefer Ace in the Hole.

2. Kids showed more strength of aggression after Ace in the Hole.

3. Kids showed more guilt and anxiety after Ace in the Hole.

What can we say except—Alex Lovy, it looks like you’re all Aces. Yet remember, let’s temper any enthusiasm that this constitutes some triumph for the Woody cartoon over the Iwerks cartoon. That’s because, in each of these three cases, the research data showed insignificant difference. Really it was a stalemate. Nothing at all could be gleaned from the small margins separating the C group and the E group.

She may have gotten aggressive drive from the kids, but the measurable impact from the cartoons was negligible. I personally think the rubber daggers and punching toy would have played a bigger role on any subsequent reports that said the kids in this study were hitting or breaking things. After it appeared in an academic journal in September 1956, the story as reported by the mainstream press began to diverge from the facts.

Because it was such an unusual and amusing story, writers probably began to impart an outcome that people wanted to hear. This has continued for decades, feeding the agenda of media critics. For example, take this sentence from an article that appeared in the Washington Post on March 29, 2002: “She showed that 4-year-olds who watched rowdy Woody Woodpecker cartoons were far more likely to roughhouse afterward than peers who watched the more mellow Little Red Hen.”

The results of Dr. Siegel’s seminal study continue to get wildly overstated and even distorted. Since public opinion is largely shaped by reports in commercial media, it’s time that this whopper of a tale—kids watched Woody Woodpecker and it made them break toys—is no longer invoked as a true story.

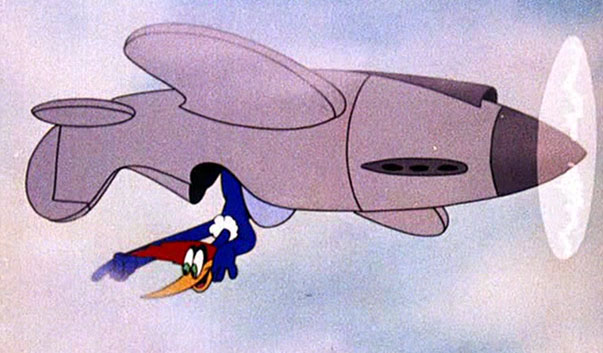

To me, one of the ironies of using Ace in the Hole for this study is that Woody is so clearly caught up in fantasy-aggression right at the outset of the cartoon, precisely what Siegel was trying to measure. Pretending to be a wartime pilot, Woody is riding around on an airplane’s shadow. He is caught up in childlike play and joins his fingers in the shape of a machine-gun. His hands jolt back, rat-a-tat, in a sequence of make-believe gunfire. He is no different than others who engage in the world through imitation.

To me, one of the ironies of using Ace in the Hole for this study is that Woody is so clearly caught up in fantasy-aggression right at the outset of the cartoon, precisely what Siegel was trying to measure. Pretending to be a wartime pilot, Woody is riding around on an airplane’s shadow. He is caught up in childlike play and joins his fingers in the shape of a machine-gun. His hands jolt back, rat-a-tat, in a sequence of make-believe gunfire. He is no different than others who engage in the world through imitation.

By our modern standards of coddling youngsters and policing their behavior, this machine-gun bit would seem appalling. But as a director, Alex Lovy understood exactly what he was doing. This fleeting sequence makes an audience see Woody as just a boy. He is naïve and impressionable. Then the sergeant grabs him by the neck. Suddenly he is thrust into an adult’s world, coping with intimidation and power. And that is what makes Ace in the Hole more engaging as a story than a cartoon about a little red hen planting wheat.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Well done Tom!

Tom, I’ve been enjoying your posts and all the new information you’ve been bringing to light concerning Walter Lantz. There’s another point about Siegel’s research which has been bugging me.

“All 24 children were scored by Siegel and her assistant Ellen Tessman to gauge their level of aggression and their level of anxiety and guilt.”

Did Siegel & Tessman know which cartoon had just been shown to the kids? If so, then their scoring could have been prejudiced.

To get an impartial scoring the observers would need to have been blinded to the test. They should have had nothing to do with the research and not even known if there was any difference between the two (and preferably more) groups.

The “C” group isn’t a control group at all. A proper control group should have been kids who had not been shown any cartoon. There should have been at least 3 groups.

Glad you’ve enjoyed them. David, to answer your question: Siegel was aware which cartoons the children had watched when she scored/observed them, but Ellen Tessman was not. I have those details in my Sept 5 post.

Interesting series. Of course Ace In The Hole is a better film than The Little Red Hen but neither are any great shakes. There are better Woody Woodpeckers and definitely better Iwerks cartoons. Lantz, of course, made his share of saccharine cartoons in the manner of The Silly Symphonies but sensibly got out after a year or two. You make some cogent observations particularly with regard to the actual educational value of animated cartoons: an area mired in spurious psychobabble (and an industry unto itself) for decades.