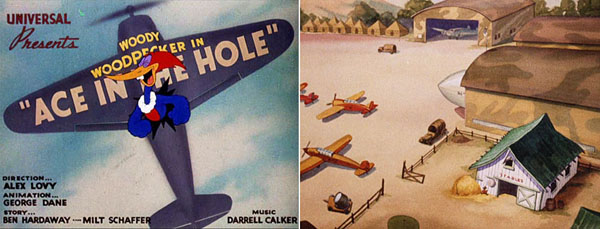

No one who worked on Ace in the Hole could possibly have anticipated what it would unleash fourteen years later because Woody Woodpecker is not even inclined to confront people in this one. He’s more of a slacker and a daydreamer, somehow able to manifest his dream-of-flying by hitching a ride on to the fast-moving shadow of an airplane. He rides along the ground and over a hangar. When he accidentally runs into a sergeant, Woody is harshly scolded.

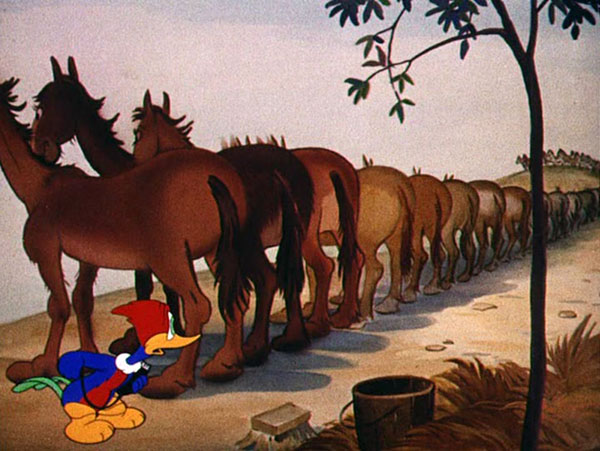

“So, still playing pilot, huh?” says the sergeant and then Woody is made to return to his duty of—you’re reading this correctly—trimming horses with electric clippers. It seems peculiar that an Air Force base is maintaining horses right next to a runway, but I digress. As I mentioned in my last post, this cartoon became the subject of a famous study on the effects of media violence on children. It would be the first of many, launching a powerful movement.

Iwerks “The Little Red Hen” (1934)

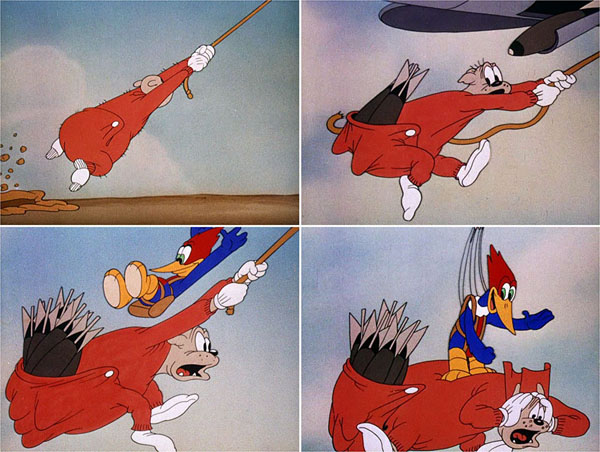

In it, Siegel says that Ace in the Hole was chosen for its “direct, unabashed, and easily comprehensible portrayal of extreme interpersonal aggression. This colored animated film depicts the conflicts which occur between Woody Woodpecker, a well-known picaresque character, and a large Air Force sergeant. Raw aggression and unrelenting hostility dominate almost every scene of this, the E film.”

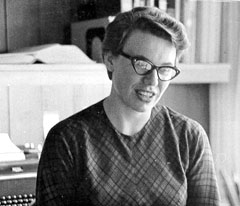

Dr. Alberta Siegel

The children participated by leaving their nursery school and walking to this made-up playroom. It was a cold Pennsylvania winter and Siegel first had to take off the boots, jackets, and mittens of her little subjects. Each kid would be paired with just one child of the same sex, both of them brought here with the incentive that they would get to watch a cartoon. Despite the cold and the snow, that was enough to make the kids want to come here. So far, so good.

The projector was set up in advance with an animated film threaded on to the reels, either Ace in the Hole or The Little Red Hen. Once the children were seated, she turned on the cartoon and then observed them for visible signs of anxiety during the viewing, placing checkmarks among a list of 29 behavioral indicators including “grips chair, winces, swallows, wets lips, sucks thumb, breathes rapidly, etc.” When the cartoon was done, she turned it off and mentioned that she had “to do some work in another room for awhile.”

At that point the two kids were left for a 14-minute period of free-play. Despite thinking they were alone, they were actually now being watched from a sound-proof room with one-way glass. Yes, this was really a pysch clinic. To provide some objectivity at this phase, Siegel recruited a graduate student named Ellen Tessman who would never be made aware which cartoon had just been shown. The two of these women gathered behind the glass at this point to observe.

At that point the two kids were left for a 14-minute period of free-play. Despite thinking they were alone, they were actually now being watched from a sound-proof room with one-way glass. Yes, this was really a pysch clinic. To provide some objectivity at this phase, Siegel recruited a graduate student named Ellen Tessman who would never be made aware which cartoon had just been shown. The two of these women gathered behind the glass at this point to observe.

The toys that were left out for the kids to play were the same for each session. Specifically they were “two rubber daggers, two soft lumps of clay, two toy telephones, four soft rubber sponges, a plastic tea set and miniature flatware, seven small toy vehicles, a doll bed containing a doll and bedding, eight inflated balloons, and a large inflated plastic punching toy.”

One of these selections is eyebrow-raising, no? Those “two rubber daggers” might just impel a kid toward mischief. When I was a boy, the mere presence of toy daggers and a punching bag would do more to juice me up and make me play rough than any cartoon I’d just watched. Then again this was done at a time when toy weapons were a staple item of American childhoods. Yet let’s not forget that this was the research that birthed an entire movement against cartoon violence. Shouldn’t it have held to a higher standard than offering its subjects daggers?

The defense against this argument was that Siegel had each pair of kids go through the test twice. In essence, each pair was their own Experiment and Control. One time they would watch Ace in the Hole and the other time it would be The Little Red Hen. Their behavior, even tempted with knives, would thereby be measurable and different if it was altered by viewing on-screen aggression vs. gentleness.

The defense against this argument was that Siegel had each pair of kids go through the test twice. In essence, each pair was their own Experiment and Control. One time they would watch Ace in the Hole and the other time it would be The Little Red Hen. Their behavior, even tempted with knives, would thereby be measurable and different if it was altered by viewing on-screen aggression vs. gentleness.

She also measured their interest in the films. However, it is not clear if the subjects were asked which one they liked or if it was inferred through observation. I assume it’s the latter. The published research says that “each film was rated,” which in every other instance in this study is gathered by viewing and judging behaviors. Ace in the Hole got a score of 3.5 and The Little Red Hen got a 3.25, which was concluded to be insignificant, but the kids appeared to prefer Woody.

The squawking hen’s song and the musicality of the Comicolor cartoon offer a simple repetitive charm that I imagine kids would like. It’s a parable about the rewards of work. The hen plants wheat in a field, never getting any help from three lazybones to whom she appeals, and then at the end of the film she alone enjoys her fresh-baked bread.

Ace in the Hole is one of Alex Lovy’s solid entries into the Woody series, but it really does take some time for the aggression to build. There is even a long sequence of Woody fumbling and dropping a flare into his zipped-up flight suit. This is comic relief, not reciprocal violence. After it’s established that the Air Force sergeant is domineering, Woody’s caper in finally flying off with a plane seems vindicating because we can sympathize with him.

Then, at the end of the cartoon, with the sergeant clinging to the airborne warplane, Woody’s latent insanity suddenly lets loose. He gives his signature laugh and fills the sergeant’s drop-seat with so many bombs that his underwear—they used to call it a union suit—bulges at the flap with explosives. He falls to the ground below and then BOOM! Pure cartoon violence, as clinically deviant as Siegel could have possibly brought to light.

Nonetheless, it falls short of her description as “unrelenting hostility dominat[ing] almost every scene.” It really only gets raw, in my opinion, at the end. It also has a parable ending, with Woody now required to trim every horse in a very long line, which is not much different in tone than the Little Red Hen offering her fresh-baked bread to the layabouts and then spitefully retracting it to make a point. In both cases, the slackers get what’s coming. Then, just as the film ends and the lights come up in the playroom, the nice lady leaves and the kids get to choose a toy—knife or tea set?

It is kind of amazing that Siegel achieved such a degree of fame for this study. She was only 24 years old and then mailed in her dissertation to Stanford to receive her doctorate in absentia. When she wrote a shorter summary as an article to appear in the journal Child Development, it was picked up by news outlets and, despite her admission of inconclusive findings, the subsequent coverage by American press gave this new field an instant credibilty. Without a doubt, Dr. Siegel was its rising star. Cartoons were under scrutiny.

Living in our violent society today, the debate on the role of media can take on a grave and somber tone. However, that shouldn’t be grounds to excuse the myth that developed around this early research, that watching Ace in the Hole provoked these kids to behave worse. In fact, Woody Woodpecker seems to have taken a bum rap on this one. In my next post, we’ll go a little deeper into this famous study to have a look at how the details were distorted over time.

I don’t want to appear to disparage Dr. Alberta Siegel. In fact, I quite admire how much she accomplished in her life as a scholar and an advocate for causes important to her. If someone has more information on this topic, or knows anyone involved with it, I’d be grateful for a message below, especially from the viewpoint of a pediatric psychologist. My attempt to shed some light on this—to set the record straight—is something that I think she too would support. Otherwise we’re just setting out a rubber dagger.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Considering that one of the items the new UPA studio was praised the most for in the early part of the 1950s wasn’t simply its visual break from the Disney style, but it’s conceptual break from the Warner Bros. style of humor, it wouldn’t be a shock to find those not just wanting to praise UPA but to find ways to shut down the type of animation they disdained would be on the lookout for a study such as this to bolster their point of view.

That would simply make Dr. Siegel’s study the first dagger on the shelf that critics of the most popular style of theatrical cartoons could find to start slashing away at the animation they already had a preconceived disposition to dislike. If this study hadn’t come along to justify the future censorship, something else would have filled the bill.

Bum rap indeed for Woody. But if the Doctor herself admitted the test was inconclusive , it’s the media’s sensationalism that is to blame. To this day they ( news media) report ” scientific” tests without citing tester , group samplings , and leaving the conclusion in the mind of the listener or inferring the conclusion.

It should be pointed out that the cartoons were originally created to round out the bill for an evening of cinematic entertainment–the original target audience for theatrical cartoons was adults, not children. A four-year old child is unlikely to comprehend, except in a general way, the nuances of the satirical humor in the Woody cartoon. Unless they are raised in a military family, they probably wouldn’t get the military spoof.

It seems a little incongruous to me to use adult entertainment to try to measure the reactions of children.

The good Doctor’s study was only one more attempt to try to control what kind of entertainment children would receive.

There had been attacks on “dime novels” in the Nineteenth Century, on pulp magazines in the Twentieth Century, and on radio adventure serials in the 1930’s. More recently had been the attacks on the comic book industry, which led to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, an attempt at self-censorship designed to forestall the kind of Governmental action that many of the anti-comics crowd sought.

In later years, we would see the rise of Peggy Charren and the {rhymes-with-witches} of Action for Children’s Television.

Many of these people came at the issue from a Socialistic (if not Communistic) point of view, feeling that Government should dictate the content of programming, and that there should be no commercials whatsoever. They wanted only “educational” programming that would be “good for the children”.

But Children are not fools. They recognize what is “good for them”–and tend to shun it. This is why PBS’s children’s programming is not more popular with the kids than it is. The kids can recognize “spinach” a mile away–and know to stay away from it.

These “well-meaning” people got their triumph with the Children’s Television Act of 1990. And it could be argued that that Act–along with market forces–has contributed to the dearth of children’s programming on the major networks that we see today.

Kids know to stay away from PBS children’s programming? So that’s why Sesame Street has been on the air for 46 years and that show along with Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and The Electric Company have been part of mainstream popular culture for decades?

In later years, we would see the rise of Peggy Charren and the {rhymes-with-witches} of Action for Children’s Television.

Always be wary of rich, do-gooder housewives with too much time on their hands. See also: Tipper Gore, Terry Rakolta.

At least some people knew what made good children’s programing and how to attract kids. That’s why some children’s shows lasted for so long.

And even Chuck Jones with Pogo (as already-blogged about years ago) and the Raggedy Ann/Andy special a decade later would be the polar opposite of his Road Runner shorts…

Friz Freleng’s 1937 effort “Clean Pastures” is an interesting curio. in that, AFAIK, it’s the only cartoon to get banned twice, once upon its initial release due to religious concerns, and the second time in 1969 over racial sensitivity concerns (though in places like New York, it had already been yanked from regular rotation). The former concern would in general be considered censorship from the right, the latter from the left, even though either way, the cartoon still has merit with a fabulous music track excerpted almost in full on the “That’s All, Folks!” CD a decade ago.

All that’s going a long way to say people will crop up demanding to censor things on a continuing regular basis, and it then becomes up to the owners of the cartoons (and society in general) to decide where the line’s drawn between something that’s considered truly beyond the pale, and something that’s simply a pressure group trying to make a name for themselves by picking out an easy target and then claiming they’re demanding censorship “….for the children..”

Given the level of violence some of the same scolds tolerate in other forms of media today, whether it’s movies, premium cable channels or multi-media video games, those still getting the vapors over Woody releasing bombs into his sergeant’s undies, or Daffy taking multiple shotgun blasts from Elmer to the face, are simply professional scolds who don’t like the idea of slapstick cartoon violence in general. But instead of just turning off the TV or computer for themselves or their families, they want to censor or legislate it out of existence for everybody (which again, is nothing new — those critical words of high praise for the Gerald McBoing Boing Show that Jim Korkis mentioned in his Friday post was nothing more than the arbiters of culture from the 1950s telling the children and everyone else of the time to eat their animated spinach, just not the kind where someone then beats the bejeezus out of someone else to the audiences’ entertainment).

I really appreciate these articles, Tom. It’s amusing that the study was based on two cartoons everybody and their grandpa had thanks to Castle Films. I wonder how the wind would’ve blown if she used Who’s Cookin’ Who? instead?

…and despite all the censorship and suppression of old cartoons, supposedly to make children less violent…we got Columbine, the Holmes massacre, the massacre in the Black church, etc. etc. You can’t socially engineer children by controlling their media, if they want to kill, they will do it anyway.

Thank you Mr. Kausler!

I was born in 1954. I share the dislike for censorship that was common in that era. When I watched the movie Goldfinger in a Kansas movie theatre when it was first released the state film board had ordered the scene with the dead gold painted woman delete from the film. Censoring adults is much more inexcusable than helping parents decide what their children should watch.

I was amused by the comment that wanting the government to decide was socialism. No, that is totalitarianism. But it was really a free social culture worried about the effects of other people’s views on children – the future generation.

Children will always be forced to endure censorship from their parents. It was parents seeking help in raising their children that these studies were for. And considering the paranoid Cold War era it is no surprise to me that such studies based on “science” as this one were accepted as fact.

Going off-topic, what I like to know is why they decided to use Iwerks’ version of “Little Red Hen” instead of Disney’s “Wise Little Hen”. I find the latter to be more memorable and it doesn’t hurt that it marked the debut of a another character that has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Castle Films donated the prints. Disney was wise enough to not sell their older post-Oswald stuff to TV and home movies…..

To PARAMOUNTCARTOONS: I don’t know who to disagree with first here, the Fox News crowd who are still seeing reds under their beds, or you. But rather than politicize this column any further, I’ll choose you.

Walt Disney’s cartoons certainly were available on TV and home movies in 1955, when this study was made. The Mickey Mouse Club, an hour each weekday, debuted that year on ABC to great success. As for home movies, Disney had for some 30 years a licensing agreement with Hollywood Film Enterprises Inc., a leading film laboratory and a competitor to Castle, to release their cartoons in 16mm and 8mm.

It isn’t specified here what type of projector was used; many of the HFE Disney releases were excerpts in silent “toy projector” lengths of 50 feet 8mm/100 feet 16mm, but by the 50’s there were nearly-complete 8mm 100-foot silent versions (not sure off hand about 16mm) and a small number of 200-foot 16mm sound titles (about a dozen Mickeys, one Donald Duck and one Silly Symphony) that were as much a staple in local 16mm rental libraries as the Castle cartoons.

In the same footnote from which I found that Siegel was screening Lantz’s “Ace in the Hole” she also gave some info on the Iwerks’ cartoon she used: ‘C film: “The Little Red Hen: Background for Reading Expression.” David A Smart. Coronet Instructional, MCML. The instructional and hortatory sequences in this film were cut from the print used in the research.’ So, despite the fact that she could have obtained it from Castle Films, she apparently used a 1950 Coronet educational title and clipped “The Little Red Hen” out of it. This I believe would have been 16mm, so the Lantz cartoon would likely have been 16mm too, in her effort to minimize the differences between the two in all ways but content. She states that “Ace in the Hole” was a ‘Universal Picture’ but not whether it was a public-issue Castle Films version, as I had speculated earlier.

I enjoyed all your comments. Let me try to collectively answer some. Yes, I agree that if Dr. Siegel hadn’t conducted this study that there would have been another one like it, that amid concerns of television entering the home, the time was ripe for someone to offer a basis to justify future censorship. Since she was honest about the shortcomings of this initial study, I also agree that the culprit was American media trying to sensationalize a story. I’m not entirely certain who first spun the story wrong, but I do know that the results have been consistently WRONGLY reported in the last few decades by mainstream news sources. In looking back at the modest means that she had to conduct this, I tend to agree with Thad that she likely chose these two films because they were readily available from Castle Films. Disney’s Wise Little Hen was not. Also, Dr. Siegel was not a millionaire who maintained a vanity crusade; she was a humble professor. I’m highly suspicious of righteousness too, but Alberta was an interesting figure. She was both the lightning-rod that inspired this field and then a journal editor who placed high demands on researchers. She also had to operate within the chauvinism of academe at that time, becoming the first tenured prof at Stanford’s medical school and by one source she admitted having to navigate amid a man’s world. It was a bit of a fluke that her dissertation became so highly cited, yet I feel obligated to shine some light on the original work because it’s become so foundational to this movement. More on that in two weeks. So far, it does have the perfect intrigue of a ToonTown mystery: rubber daggers!