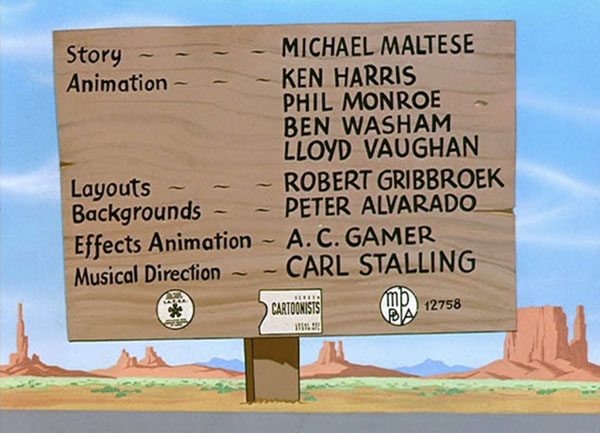

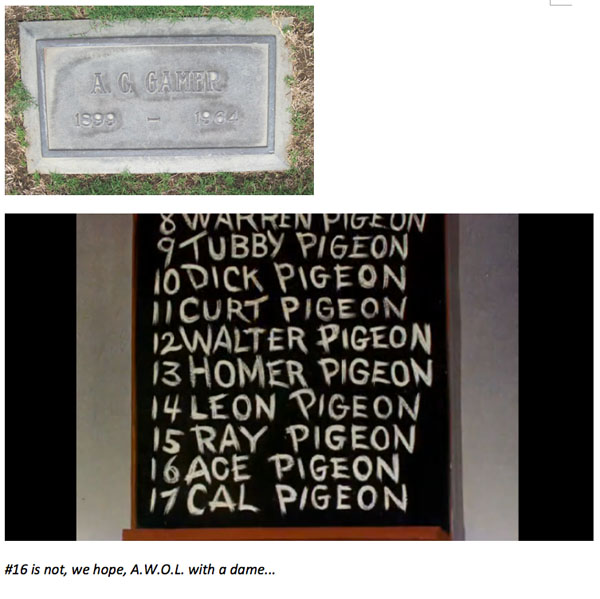

The credits for “Fast And Furry-ous” (1949)

When Chuck Jones succeeded Frank Tashlin as director of the “A” unit at Leon Schlesinger Productions in the spring of 1938, the animation team he inherited carried over to the first cartoon he directed, The Night Watchman, which was released on November 13th of that year. The “breakdown” for this cartoon is available, and was previously discussed here on Cartoon Research(1). A number of the names of the animators are quite familiar: Phil Monroe, Ken Harris and future director Bob McKimson. Ben Washam and Rod Scribner, then at the start of their careers, also animated short sequences in the cartoon.

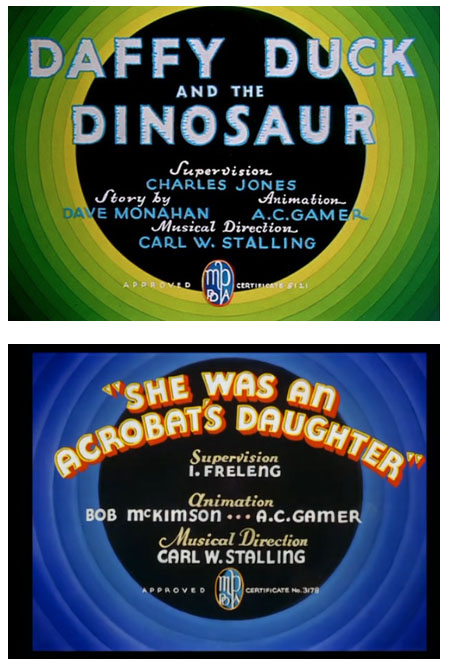

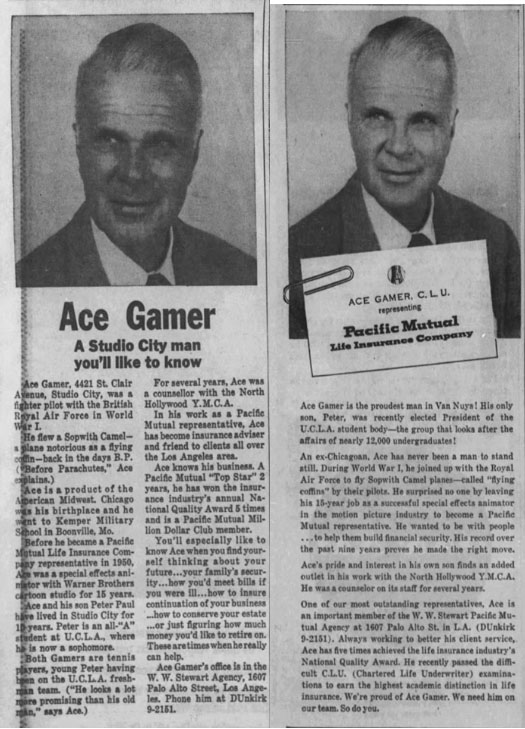

One animator’s listing in the breakdown is called out by Devon Baxter as unusual. It is for an “Ace,” namely, A.C. Gamer. Baxter notes that Gamer was typically an effects animator, and in general, that is how he is remembered. For example, Chuck Jones in his memoirs refers to Gamer as an effects animator, and the bulk of Gamer’s on-screen credits came in the post-1944 era, when he was listed as such.

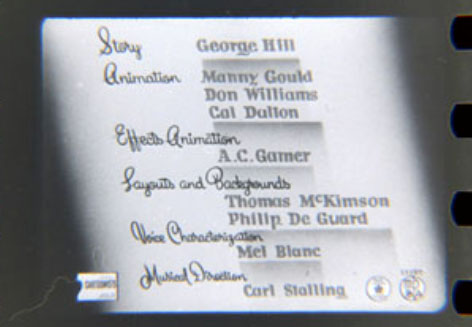

Part of the credits sequence from Arthur Davis’ cartoon “Mouse Menace,” released November 2, 1946, which lists A.C. Gamer as an effects animator. Previously supplied to Cartoon Research by David Gerstein.(2)

Chuck Jones, in his memoirs(3), includes a number of drawings and photographs of Gamer. In his notes to one of the photographs, he identifies Gamer as an “effects animator and World War I pilot,” surely an eye-catching designation.(4) Some of what Jones has written in his memoirs should be taken with caution, such as his descriptions of producers Leon Schlesinger and Eddie Selzer. One of the authors, for example, was intrigued by a reference to Tedd Pierce as having attended the Choate School,(5) the author’s own school; there was significant disappointment, thus, when the author was told Pierce had never gone there.

Nevertheless, there is one notable piece of contemporary evidence regarding Gamer’s career as a pilot, which has also been published here on Cartoon Research.(6) “The Exposure Sheet” was an in-house publication at Leon Schlesinger Productions which contained a variety of items, including short biographies of various studio personnel. Issue #2, dating from approximately January, 1939, has this to say about Gamer:

“AN ANIMATOR: Chicago was the birthplace of Ace Gamer. From grammar school there he went to a military school in St. Louis. When he enrolled he made the mistake of laughing at an officer’s toothache and was put on the black list. To fill out the day, he broke both thumbs – one when an upperclassman called him “Rat”. In Los Angeles, Ace went to L.A. High for one year, then went back to St. Louis. When war broke out, Ace, only seventeen, was accepted by the British Air Service [sic – EOC]. But by the time he reached New York, an agreement had been signed against enlisting men from foreign countries. But somehow the name “St. Louis” on the pass issued for his return was mysteriously changed to “Toronto, Canada”; and thus Ace joined the Royal Air Corps [sic – EOC] and received his wings. After the war, Ace returned to St. Louis, and for the next eight years worked for a lumber company. He studied art at the Chicago Art Institute, and finally came back to Los Angeles. Here he studied at Chouinard [i.e., Chouinard Art Institute, absorbed in 1961 into CalArts by merger with the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music, and also notable as Chuck Jones’ alma mater, among many, many other animation personnel – EOC], and finally came to Schlesinger’s. […]”

Certainly, this excerpt shows that during his active career at Leon Schlesinger/Warner Bros., Gamer was said to have been a pilot (“received his wings”) in the Royal Flying Corps. Of course, these kinds of claims must be taken with a degree of caution. An excellent example of this is the novelist and screenwriter William Faulkner (who also had an interlude at Warner Bros. in the 1940s – not in animation, of course!). For a number of years, there was controversy over whether or not Faulkner had enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps or the Royal Air Force; the current thinking is that Faulkner did, in fact, enlist in the Royal Air Force in approximately July, 1918, but his training had not been complete by the time the Armistice occurred in November, 1918, and he does not appear to have either “earned his wings,” or had been given an officer’s commission.

Thus, we have to trace what we can about the life of A.C. Gamer. Fortunately, there is a family tree on ancestry.com which includes him, and we can follow along his early life. Adolph Charles Gamer was, indeed, born in Chicago, on May 13, 1899 (note the date – this will be important later). Gamer’s father, George, was involved in the furniture business, and was married to Hady. Both the maternal and paternal grandfathers, as well as the maternal grandmother, were listed in the 1900 federal census as having been born in Germany. A brother, Edward, and a sister, Haidee, were born in 1902 and 1906, respectively, and are listed in the 1910 federal census, which lists A.C.’s mother as “Hedwig,” and does not list the father; the family was living with relatives in St. Louis, Missouri. Late in life, an advertisement featuring Gamer states that he went to the Kemper Military School in Boonville, Missouri (again, a fact consistent with his “Exposure Sheet” biography).(7)

At the time of the declaration of war by the United States on the German Empire in April, 1917, A.C. Gamer would have been just short of his 18th birthday. The authors have not been able to trace any World War I draft registration card for Gamer.

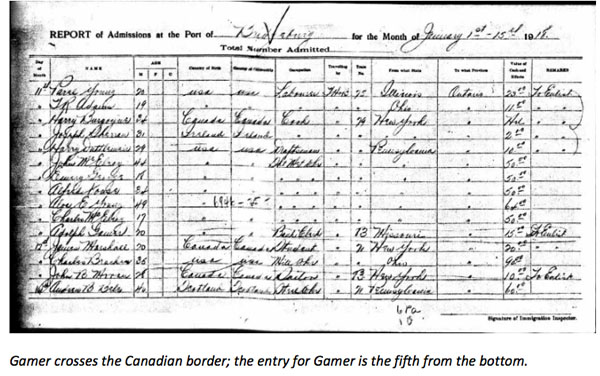

The next trace of Gamer comes from a border-processing document; on January 11, 1918, Adolph Gamer, 20 years old, occupation bank clerk and with an address listed as Missouri, is listed as having crossed the border at Bridgeburg, Ontario (across the Niagara River from Buffalo, New York) with the purpose of enlisting. Into what branch of the forces Gamer intended to enlist is not stated, but it is noteworthy that Gamer has slightly lied about his age, changing it from 18 years, 8 months to 20 years.

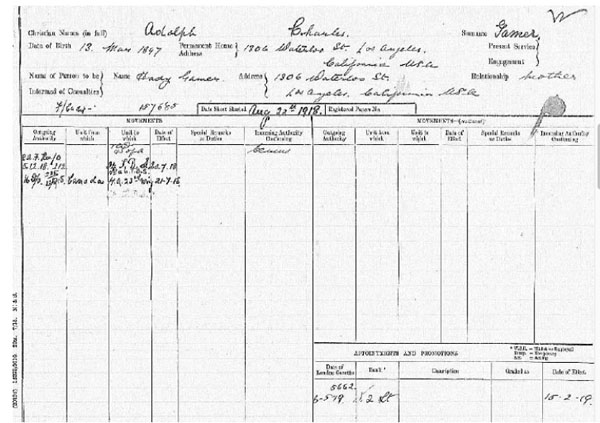

From here, one has to search the records of the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force to find traces of Gamer. As noted above, the Royal Flying Corps was subsumed into the Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918. There exists, in the U.K. National Archive, a list of officers who served in the Royal Air Force. This database is known as “AIR 76.” Searching this database turns up the following:

“Adolph Charles Gamer, born 13.03.1897, AIR 76/175/42”

The code number provides the reference from which Gamer’s service record can be pulled.

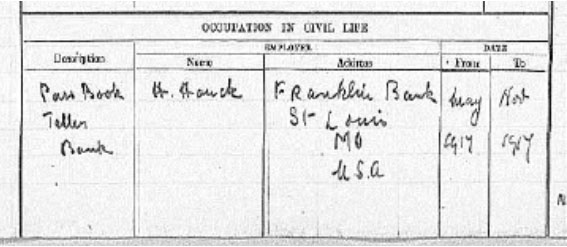

A number of interesting points can be drawn from this record. In the first place, we are given the information that Gamer’s alleged birthday was May 13, 1897; 2 years earlier than his true birth date. From May, 1917 (i.e., approximately his 18th birthday) to November, 1917, Gamer was employed by the Franklin Bank of St. Louis as a teller, which is consistent with the border crossing record, and with the account given in ‘The Exposure Sheet,” which said he was living in St. Louis “when the war broke out,” though his home address, and that of his mother Hady, is listed as Los Angeles. Gamer was assigned a serial number (157685).

The record of his “movements” in the middle-left corner of the sheet is a bit hard to translate, owing to handwriting and the use of initials, but one entry stands out clearly: Gamer was assigned to the HQ of the 23rd Wing, effective July 21, 1918. The 23rd Wing, established November 13, 1916, was a training wing, indicating that in July, 1918, Gamer started his formal aeronautical training.(8) The term “T.D.S.” likely means “Training Depot Station.”

The training process occurred in a number of stages, which are described by the Royal Air Force Museum at its website.(9) It took approximately nine months for an aspirant to receive a commission, based on two months in a cadet wing (drill, physical training, Morse code, military law and map reading), two months at a school of military aeronautics (aviation theory, navigation, the working of aero engines, &c.), a three month period at a Training Depot Station (a minimum of 25 hours flying training), and then a further two month period at a Training Depot Station (a further 35 hours of flying training and gunnery training, including time on modern planes), after which successful cadets were commissioned.(10) To formally earn pilot’s wings, a commissioned officer would then complete an appropriate specialist school (e.g., fighter or bomber or recon), meaning a total of eleven months would usually elapse from the start of cadet training to the receipt of the wings.

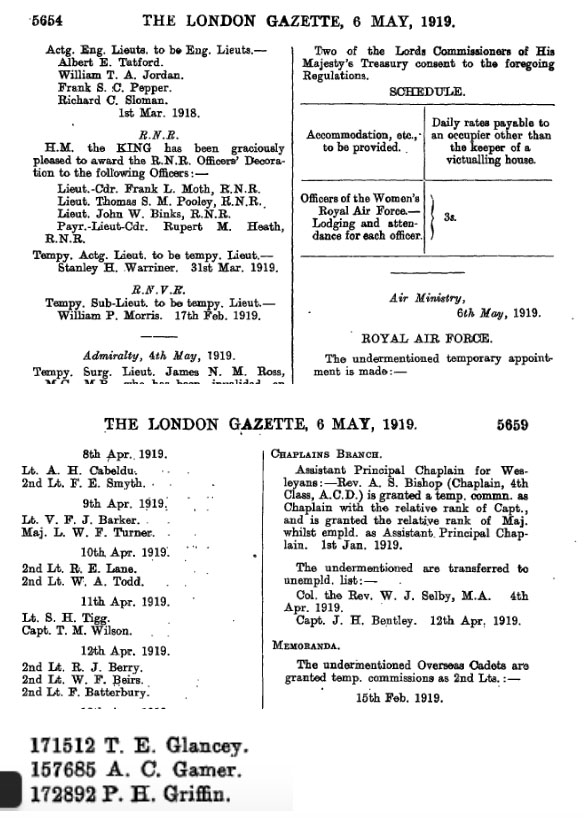

Gamer’s service record shows unequivocally that he had completed training through the receipt of a “temporary commission.” The receipt of this was, as per custom, published in the official publication, The London Gazette, on May 6, 1919, with an effective date of February 15, 1919.

Extracts from the May 6, 1919 edition of The London Gazette, showing the grant of a temporary commission as 2nd Lieutenant to overseas cadet A.C. Gamer, serial no. 157685, effective February 15, 1919.

The record does not indicate that Gamer ever saw combat; that he saw combat is unlikely, given that he was assigned to a Training Depot Station in July of 1918, four months before World War I ended; additionally, there is no record of his assignment to a combat squadron. If Gamer was assigned to a Depot Training Station in July, 1918, he likely completed his basic flying training some time around December, 1918. In theory, Gamer could have completed his specialist training by the time of the effective date of his commission in February, 1919, though his service record is silent as to movements after July, 1918.

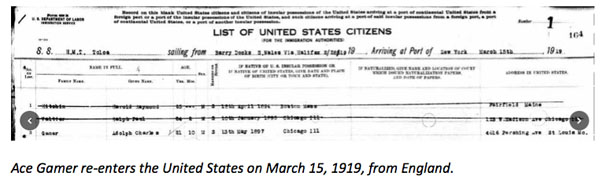

Gamer left the U.K. from the Barry Docks in South Wales on the troopship H.M.T. Toloa on February 28, 1919, and arrived back in the United States in the port of New York two weeks later, on March 15, 1919, listing a home address in St. Louis; also a false birthdate of May 13, 1897!

While Gamer was not an “ace,” in the generally accepted usage of the term (that is, he did not shoot down 5 enemy planes, and did not even see combat), the clear facts are that Gamer made extraordinary efforts, inclusive of lying about his age, in order to volunteer for a dangerous branch of the service. It also clear that Garner was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force; whether he received his pilot’s wings formally (as his miniature biography in “The Exposure Sheet” states) or not appears to be something of a technicality, and is unclear. It is worthy of note that Gamer was further along in the process of training than either William Faulkner, or detective novelist Raymond Chandler, who was also undergoing training in the RAF at the same time Gamer was.(11)

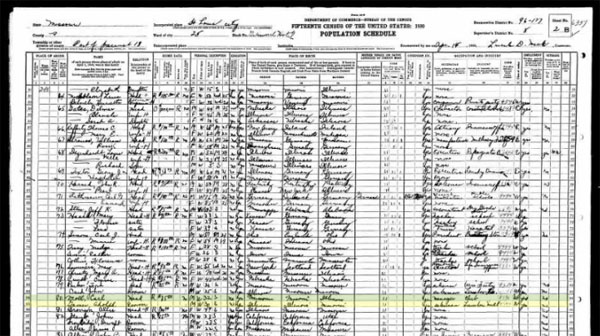

The authors have not been able to trace Gamer in the 1920 federal census. However, in the 1930 federal census, he is listed as living in St. Louis, and working as a salesman for a lumber mill; again, this is consistent with the information presented in the miniature biography in “The Exposure Sheet.”

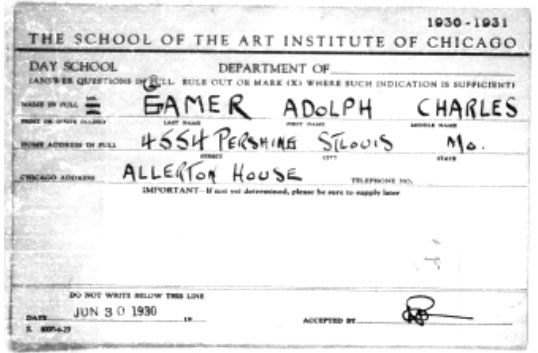

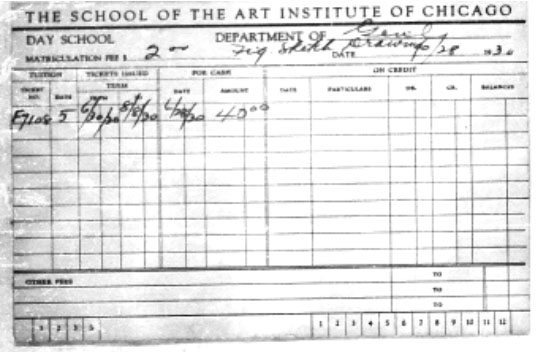

Material provided to the authors by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago shows that Gamer attended classes in figure sketching between June and August, 1930, again consistent with his miniature biography. He is still listed as having a St. Louis address at this time.

The authors have made efforts over a period of months to see if Chouinard’s records contain references to Gamer. The Registrar’s Office at CalArts has explained to one of the authors that graduation and enrollment documentation was not maintained by Chouinard, or the records have not survived; only individual class records, written out by hand, survive, and as of February, 2019, no records mentioning Gamer have been located, though research was continuing. This is the only part of the miniature biography in “The Exposure Sheet” that the authors have not found some backing for, but it is still possible that Gamer may have attended classes at Chouinard, with the records still to be found.(12)

The October, 1947 issue of the “Warner Club News” (the in-house publication of Warner Bros.) indicates that Gamer joined Leon Schlesinger Productions in early 1933, just before Chuck Jones joined the studio (13); later materials indicate that Gamer spent 15 years at Schlesinger/Warner’s, ending in 1948, so a 1933 start date appears to be probable.

Between 1936 and 1940, Gamer is given on-screen credit for a small handful of cartoons(14); given the haphazard nature of credit assignment in the era by the Schlesinger studio, it is difficult to determine how great Gamer’s contributions were to each cartoon where he was credited, or where he was not credited. The self-caricature of Gamer that appears in Chuck Amuck is from a 1940 Christmas card to Chuck Jones from his unit and the “S.E. Dep’t,” which quite possibly means Gamer.(15)

During this period, Gamer married Jane Weaver (1918-1990) on August 23, 1937, and his only child, Peter Paul Gamer (1938-1995), was born on December 11, 1938. By the time of the 1940 census, Gamer was earning $2,280 a year in his position at the Schlesinger studio.

The early to mid 1940s were a period of great union activity in the animation industry, and A.C. Gamer appears to have been in the forefront of such activities. The July 20, 1945 edition of Top Cel, a publication for East Coast animators, congratulates Gamer upon his election, in June of 1945, as the president of the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild (SCG) Local 852.(16) “All of us remember Ace,” the article says, “as one of the charter members of the Hollywood Guild and as an active and militant member since the inception of the union. We are sure that he will be one of our best Presidents.”

Previously, the July 14, 1944 edition of Top Cel had noted that Gamer had been elected as “Conductor” of Local 852. The December 29, 1945 edition of The Los Angeles Times carries an account of Gamer testifying at the trial of Herbert Sorrell, in connection with contempt of court proceedings growing out of the violent October, 1945 strike at Warner Bros., where the SCG had participated in the picketing, but had not itself struck WB. Gamer, who testified that he was at the far end of the picket line when the clashes broke out, described the clashes that broke out. Tom Sito, in his book Drawing the Line, has slightly different information, stating that Gamer was president of the SCG in 1946, and was succeeded by Art Babbitt.(17)

With the advent of more complete on-screen credits in the mid-1940s, Gamer received more recognition for his work as an effects animator, with his work spread out among the Freleng, Jones, Davis and McKimson units at Warner Bros.

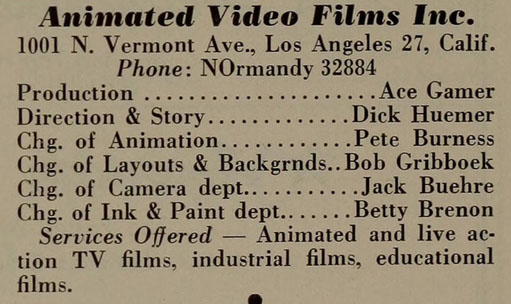

Gamer appears to have left the Warner Bros. cartoon studio in late 1948, with his last on-screen credits at the studio coming in 1949; he was succeeded in his role as effects animator by Harry Love. An article carried in Variety in October, 1948 indicates that Gamer and Murray Youlin had formed a firm known as “Animated Video Film Co.” The 1950 and 1951 editions of the Radio Annual carry a listing for Animated Video Films Inc., located on North Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles. Ace Gamer is listed as “Production” in these entries, with long time Disney staffer Dick Huemer listed as “Direction and Story,” Pete Burness as “Chg. Of Animation,” and former Jones unit background artist Bob Gribboek listed as “Chg. of Layouts and Backgrounds.” The services offered related to “animated and live action TV films, industrial films and educational films.” Richard Huemer, the son of Dick, noted (in a comment posted here to Cartoon Research) that his father had founded the firm with Gamer, “but they didn’t get much business. Their most memorable [work] was the Buster Brown spot, which many people remember: “I’m Buster Brown, I live in a shoe; that’s my dog Tighe, he lives in there, too.” Huemer went on to note that “the shoe people ordered many flip-books for their annual shoe convention.”

Huemer went back to work for the Disney studio in 1951, and Gamer appears to have moved into the insurance business, becoming a Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company representative in 1950. Advertisements for the W.W. Stewart Agency, where Gamer worked, that appeared in 1957 and 1959 (18) note his interest in tennis (an interest he shared with his son, who played tennis for UCLA and was president of its student body) and his role as a counselor for the North Hollywood YMCA. The advertisements note prominently his World War I service in the RAF; even late in life, he was proud of his role as a “captain of the clouds.”

Gamer died June 9, 1964, and is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale.

FOOTNOTES

1 – Baxter’s Breakdowns: Chuck Jones’ “The Night Watchman” (1938), by Devon Baxter. https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/chuck-jones-the-night-watchman-1938/

2 – Mel Blanc: From Anonymity To Offscreen Superstar (The advent of on-screen voice credits), by Keith Scott. https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/mel-blanc-from-anonymity-to-offscreen-superstar-the-advent-of-on-screen-voice-credits/

3 – Chuck Jones: Chuck Amuck (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1989) Chuck Jones: Chuck Reducks (New York: Warner Books, 1996)

4 – Chuck Reducks, page 82.

5 – Chuck Amuck, page 112.

6 – The Exposure Sheet #1 and #2, by Jerry Beck. https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/the-exposure-sheet-1-2/

7 – The school no longer exists, having closed in 2002. The State Historical Society of Missouri-Columbia Research Center has the records. https://collections.shsmo.org/manuscripts/columbia/c4005.html

8 – Air of Authority – a History of RAF Organisation http://www.rafweb.org/Organsation/Wings1.htm

9 – https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/taking-flight/pathway-to-pilot/first-world-war.aspx

10 – Ibid.

11 – https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/100-stories/Pages/chandler.aspx Chandler’s AIR 76 record indicates that he was a few days behind Gamer in having a record opened in August of 1918. Chandler had previously served in the infantry on the Western Front.

12 -Just before publication, the authors received word from CalArts’ registrar’s office that Gamer attended Chouinard in 1946 and 1947, which is some years after the reference in the “Exposure Sheet.” This, as will be seen, would have been late in Gamer’s tenure at Warner Bros. The 1939 reference in the “Exposure Sheet” is still obscure.

13-See: Warner Club News (1947) by Jerry Beck https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/warner-club-news-1947/#prettyphoto[39632]/2/

14 – She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter (Freleng, 1937); Dog Daze (Freleng, 1937); and Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur (Jones, 1939). As noted above, there is documentation showing Gamer worked on The Night Watchman (Jones, 1938). Copyright records indicate that Gamer was also credited on You’re an Education (Tashlin, 1938) and Sweet Sioux (Freleng, 1937).

15– Chuck Amuck, page 112.

16 – Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists Local 839, IATSE, is in some respects the successor of Local 852, SCG. 839 was formed in 1953 after winning an election against 852 in 1952. For details, see Tom Sito: Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson (Lexington: the University Press of Kentucky, 2006) 852 was merged into the Teamsters union in 1971. https://animationguild.org/about-the-guild/local-839/

17 – Sito identifies Gamer as “Al Gamer.” [sic] Drawing the Line, page 354.

18 – Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1957 and September 23, 1959

DEVON BAXTER is a freelance video editor, currently residing in Pennsylvania. He has provided vintage material and edited supplemental features for Tom Stathes’ Cartoons on Film Blu-Ray/DVD sets.

DEVON BAXTER is a freelance video editor, currently residing in Pennsylvania. He has provided vintage material and edited supplemental features for Tom Stathes’ Cartoons on Film Blu-Ray/DVD sets. E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

Gamer was in St. Louis in 1920, listed as a travelling salesman in the city directory (pg. 1271).

The St. Louis Post Dispatch of February 14, 1922 reported:

Youth In Taxicab Badly Injured When Another Machine Hits Car.

John McDermott, 19, of 3814 West Pine boulevard, suffered concussion of the brain at 11:45 last night when thrown from a taxicab in which he was seated, after It was struck by an automobile driven by Adolph C. Gamer, 26, who gave his address as 4549 Pershing avenue. The taxicab was parked In front of 5406 Delmar boulevard when it was struck by the Gamer machine, east-bound.

Gamer left his name and address with witnesses and was arrested at 1 a. m. today and taken to the city hospital. He was later taken to the Page Boulevard Police Station, where he admitted his car struck the taxicab, but said he did not see it in time to avoid a collision. He said he had attended a banquet earlier in the evening. Police charged him with driving an automobile when intoxicated.

Evidently Gamer was still lying about his age in 1922, claiming to be 26 when he was really only 22.

That’s some very impressive research, gentlemen, and congratulations on an outstanding job! Unfortunately very little of A. C. Gamer’s personality seems to emerge from his military and employment records. I find it interesting that, after having boosted his age to fly with the big boys during his military service, at Schlesinger Gamer worked with men who, by and large, were at least ten years younger than him. Of all his colleagues, only Ken Harris would have been around the same age. Also, Gamer married a woman nineteen years his junior. Perhaps his decision to enter the insurance business at age 50 might have been motivated by a desire for stability in his life that show business could not provide.

It’s interesting that, other than Disney, Warner Bros. is the only cartoon studio in the classic era that listed effects animators in their credits. I imagine that is because most studios didn’t have effects specialists, but I wonder how many effects animators were working at studios like MGM or Famous Studios without getting proper credit. I reckon that might make an interesting post one day.

Al Grandmain was at MGM and Sid Pillet at Lantz.

Very good work, Devon and E.O.! I guess there are no drafts still existing that determine if Ace Gamer started as a character animator, and in which cartoon he started to do effects? I wonder if he animated that terrific air brush explosion effect that Warner Bros. Cartoons used into the early 1950s? It was always accompanied by a powerful sound effect, probably supplied by Treg Brown.