We have “The Gong Show” to thank for The Little Mermaid, Disney’s 1989 hit that kicked off their unprecedented Renaissance era of animated films.

At the Studio, “The Gong Show” meetings were modeled after the self-named game show/talent show of the 1970s, where acts would come and perform. Celebrity judges would sound a gong if they didn’t care for the act, but the performers moved forward if there was no gong.

Disney adopted this model for their “Gong Show” – artists could “pitch” story ideas for future animated projects. If the pitch wasn’t met with a “gong,” it moved forward to potentially become a Disney animated feature.

Disney adopted this model for their “Gong Show” – artists could “pitch” story ideas for future animated projects. If the pitch wasn’t met with a “gong,” it moved forward to potentially become a Disney animated feature.

Director Ron Clements pitched the idea for The Little Mermaid at one of these meetings. Clements found Hans Christian Andersen’s story while browsing through a bookstore. It wasn’t “gonged” in the meeting after he pitched it, and it went forward into production.

“It was the first time that a whole new generation was going back to the roots of where things began, such as with Snow White,” recalled Clements in 1997. “We felt a certain intimidation because we knew that this film might be compared with those, more so, because there would be similarities. At the same time, we wanted to put a new spin on it so that it would reflect the new generation.”

Thirty-five years later, The Little Mermaid, which Clements co-directed with John Musker, has most definitely achieved that. The film allowed a new generation of Disney animators to finally stretch their artistic wings and a new generation of audiences to discover (or re-discover) all that Disney animation could achieve.

The Little Mermaid was considered a project at Disney as far back as the late thirties when Walt looked at the potential of a “package film” spotlighting several of Andersen’s stories. It was to have been a live action/animated film. Biographical-like segments of Andersen’s life would be intercut with animated vignettes depicting his stories, including The Little Mermaid.

Kay Nielsen paintings for an earlier proposed Little Mermaid.

The feature never came to be, but while doing pre-production work for the film, Clements and Musker spent time at the Walt Disney Animation Studios Research Library, where their team came across conceptual artwork done for Walt’s initial version of The Little Mermaid. This included art by illustrator Kay Nielsen, who had provided the striking artwork for the Night on Bald Mountain sequence of Fantasia (1940).

Neilsen’s work offered such inspiration that he was given posthumous credit on The Little Mermaid.

The film would tell the story of young Ariel, the mermaid fascinated with the human world against her father, King Triton’s wishes, so much so that she strikes a deal with the villainous sea witch, Ursula. Ariel trades her lovely voice for a pair of human legs so she can go ashore to find Prince Eric, with whom she has fallen in love.

Ariel will remain human for three days. If she receives love’s true kiss from Eric, she will stay human permanently. If not, she transforms back into a mermaid and will belong to Ursula.

The Little Mermaid boasted a voice cast that included Jodi Benson as Ariel, Samuel E. Wright as Sebastian, the crab, the King’s court composer and Ariel’s conscience, of sorts, Pat Carroll as Ursula, Kenneth Mars as King Triton, Buddy Hackett as Scuttle the seagull, Christopher Daniel Barnes as Prince Eric, Rene Auberjonois as Louis, Eric’s chef and Paddi Edwards as Flotsam and Jetsam, Ursula’s moray eels.

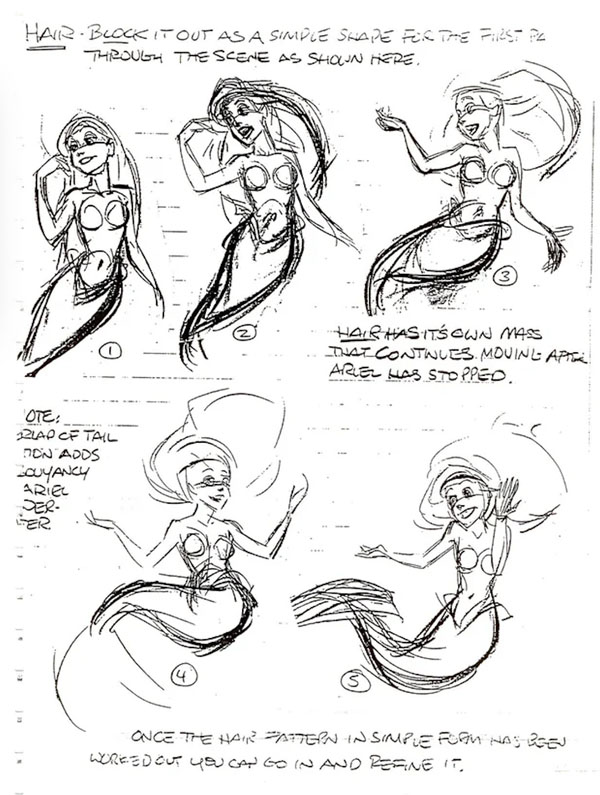

The film also boasted a cast of talents when it came to animators, which included Glen Keane and Mark Henn as supervising animators for Ariel, Andreas Deja for King Triton, Ruben Aquino for Ursula, and Duncan Marjoribanks for Sebastian.

Among the differentiators for The Little Mermaid was how music was incorporated into the story. Disney had recruited talented Broadway veteran Howard Ashman to write “Once Upon a Time in New York City” for 1988’s Oliver & Company. Ashman, along with his songwriting partner, composer Alan Menken, had crafted the hit musical Little Shop of Horrors for Broadway in 1982.

Among the differentiators for The Little Mermaid was how music was incorporated into the story. Disney had recruited talented Broadway veteran Howard Ashman to write “Once Upon a Time in New York City” for 1988’s Oliver & Company. Ashman, along with his songwriting partner, composer Alan Menken, had crafted the hit musical Little Shop of Horrors for Broadway in 1982.

The duo came on board The Little Mermaid, and it proved to be a tremendous creative catalyst. “The idea of having a musical team right in the next room, so as you were storyboarding something, you could go next door and talk with Howard and Alan,” noted Musker in 1997. “Then, they could come over and see the artwork and say, ‘There’s something there that I can use.’ In a way, that was a throwback to a system that was around in the ’30s but had gone away.”

Ashman, in particular, had an innate sense of music informing the plot, and emotion. “He brought a new sensibility, in terms of how he saw music weaving into the story, that did set all this off,” said Musker. “Howard’s involvement was a watershed and a turning point. We had never done anything like that before. It was a big learning experience for all of us. Working with Howard made us feel as if this was something special.”

Ashman and Menken’s songs in The Little Mermaid, including “Part of Your World,” “Kiss the Girl,” and the Oscar-winning “Under the Sea,” have become some of the most instantly recognizable in Disney’s songbook, and some of the most famous in movie musical history.

Ashman and Menken’s songs in The Little Mermaid, including “Part of Your World,” “Kiss the Girl,” and the Oscar-winning “Under the Sea,” have become some of the most instantly recognizable in Disney’s songbook, and some of the most famous in movie musical history.

Released on November 17, 1989, The Little Mermaid bowled over audiences, becoming a tremendous success for Disney. Many critics placed the film on their top ten list for the year and praised it.

“It’s funny, romantic and – OK – scary, just as it should be,” wrote film critic Jami Bernard when The Little Mermaid opened. “This kind of terror is enthralling, stimulating. Just as yesterday’s kids cowered at Bambi and Pinocchio, films they remember now with great affection, let today’s kids see how powerful animation can be.”

Now celebrating its thirty-fifth anniversary, the success of The Little Mermaid can be seen as a “flashpoint” for all that was to come for Disney in the next ten years. The film ushered in a string of landmark successes at the Studio, which included Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, and more.

The Little Mermaid also secured its place among Disney’s DNA of classic and timeless fairy tale films, which continues in popularity, inspiring a successful live-action adaptation last year.

“For me, personally, as far as any sense of, ‘Will the public like this?’ or ‘Will this be a big hit?’ I honestly had no sense of that,” said Musker, reflecting on the success of The Little Mermaid in 1997. “We were very innocently trying to just make the best film that we could. In hindsight, you can see how things have worked out, but I had no idea that it would reach the audience that it has and move into some of the pop cultural things the way it did.”

Again, thank you to “The Gong Show.”

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

The Little Mermaid was amazing. It was the clear beginning of what is now termed the Disney Renaissance. Gone was the generic house style of animation that had been employed in every Disney animated feature since “One Hundred and One Dalmations”. This bold new style was something of a throwback to the classic style of the 40’s and 50’s animation, yet at the same time it seemed a breath of fresh (sea?) air. It was also a return to fairy tales which had conspicuously not been a part of the Disney output for several years.

I wasn’t quite sure how the sad poignancy of the Little Mermaid’s fate would play out in a Disney feature, but I was not disappointed in that regard. The bargain with the Sea Witch is as memorable in the film as in the original Hans Christian Andersen story–and as deadly. It is also clear that the mermaid does not fully understand the implications of the bargain, blinded as she is by love. However, the happy ending does not feel forced, but rather seems the natural outcome, and one that Andersen himself might have embraced had he been more given to happy endings to his stories. After the truly horrifying ordeal that the mermaid goes through, one can even argue that the ending is justified.

My one quibble is the use of the name Ariel for the mermaid. For me, the name Ariel is forever associated with Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. It would be the same if she had been named Juliet or Desdemona or Titania–names that are firmly linked to Shakespeare’s work. I could come up with any number of names that I would have liked better for the lead character in the Little Mermaid. The other names, too–Scuttle, Flounder, Flotsam, Jetsam, even Prince Eric–to me show a lack of originality. The one name that seems perfect is Triton for the Sea King, as Triton was the son of Poseidon in Greek Mythology. That one point aside, the film is still a masterpiece.

Musically, it is also a tour-de-force. At the time it was rare for the music and songs in a Disney film to mesh so perfectly with the storyline. Again, a throwback, but at the same time a leap forward. When I first heard “Under the Sea” I was enchanted with it and couldn’t wait to hear it again.

This was also the first time in a long time that I had heard adults singing the praises of a Disney film, much like–I imagine–the reception of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 37.

The prince was named Eric as a tribute to “Nine Ole Men” animator, Eric Larson who passed away a year prior to the film’s release and was a mentor to many of the animators that worked on the film.

Thanks for that. I didn’t know. Now I can appreciate it.

“The Little Mermaid” was the last Disney movie my parents took me to see (25 years after the first, “Mary Poppins”). I was going through some hard times financially, to the point that I couldn’t afford to visit my family at Christmastime that year. So a few weeks later, my parents came to visit me on my birthday; and when they asked what I wanted to do that day, I didn’t hesitate: “I want to see ‘The Little Mermaid’!” “No, seriously, what?” But I couldn’t have been more serious.

The critical praise was far higher than I had ever seen for any animated film in my lifetime. Reviews routinely rated it as the greatest thing since “Sleeping Beauty”. I was already conscious of a burgeoning renaissance in animation: “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” had been a hit the year before, and there was also a noticeable improvement in the quality of television animation at this time. I went into “The Little Mermaid” with high expectations, and the film, if anything, surpassed them by leaps and bounds.

I liked it better than my parents did. Their taste in Disney songs ran more to cute little singalong ditties like “Whistle While You Work” and “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?”; while Ashman and Menken’s Broadway-style numbers — clever and complex yet direct and heartfelt — were perfectly in line with my sensibilities. Also, as Hans Christian Andersen purists, my parents were disappointed that Ariel didn’t die in the end. And yet they chided me for being morbid when I used to read horror stories as a teenager.

Many talented people contributed to “The Little Mermaid”, but I’d like to single out Thomas Pasatieri, who orchestrated Alan Menken’s musical score. A former child prodigy who became the first person to earn a doctorate in composition from New York’s prestigious Juilliard School, Pasatieri is a renowned composer of opera, having written over two dozen that have been produced all over the world. He has also written a large body of vocal and instrumental works, including three symphonies, and has taught at Juilliard and other elite music schools. In recent years I have given a number of recitals showcasing the music of composers who have worked in animation. The Pasatieri Viola Sonata was the centerpiece of the first of these, in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2013.

I’d also like to mention Sherri Stoner, the live-action reference model for Ariel, who has gone on to a distinguished career as a cartoon writer and producer (though I’ll always remember her best as the voice of Animaniacs’ Slappy Squirrel — now that’s comedy!) Animator Glen Keane has a condition called aphantasia, which affects the mind’s ability to form mental images; as such, he has to rely on live-action reference to a greater extent than other animators. In order to bring Ariel to life, Keane had to study young Sherri Stoner in a skintight swimsuit as she swam around in a plexiglass tank for hours on end, day after day, over a period of many months. The dedication of these people to their art is almost unbelievable.

Disney would create other animated masterpieces in the following years, but none of them will ever have the same place in my heart as “The Little Mermaid”. It will always remind me of how, at a difficult time in my life, my Mom and Dad could still cheer me up by taking me to a movie: a movie that, at least for as long as I was part of that world, made me believe in the possibility of dreams coming true.

Still my favorite movie. Amazing that it was Disney’s first fairy tale in decades because they swore them off after Sleeping Beauty’s performance in the box office 30 years (!) earlier.

One thing I must say is that the scene of King Triton laying waste to Ariel’s secret museum of human stuff – after telling her that she should have left a man to die – remains one of the gutsiest scenes in any Disney-branded film. With the sea-king, Ron, John, Andreas and the other Disney artists had their work cut out in developing a character with almost a split personality – one minute, a proud and benevolent grandfather-type figure, and the next, a growling beast with a temper that would make even Donald Duck quiver. And they had to make Triton appealing enough that, after the moment where he’d finally lose control and cross the line, we’d want to follow him as he went through a redemption where he’s left wondering if he’s truly worthy of his family’s love and ultimately deciding to sacrifice his kingdom and freedom to save his daughter from his enemy.

Perhaps the closet that came before the grotto scene it in terms of terror and styling was the dress-ripping scene from “Cinderella,” but it didn’t exactly come off as surprising narrative-wise since we knew the stepsisters didn’t like Cindy to start with. Here, Ariel saw her own father – someone she loved and trusted – completely lose himself to his inner demons and “transform” into a dark, horned demon that spitefully reduced her collection to a junk while she can only beg for mercy. It was the moment that he film become something more than a “colorful Disney cartoon fairytale” and pivoted more toward a character study; Ariel’s personality was far more jaded and cynical in the sequence that followed, letting us know that the Eric statue wasn’t the only thing Triton obliterated.

If there’s one thing the live-action remake did good, it’s be the scene where Triton listens to his other daughters wonder why Ariel would run away when the answer is right there in front of them, and then looking at his trident, emitting the same glow that made Ariel’s cavern resemble a red hellscape, and letting it fall to the seafloor as if he felt he’d proven himself undeserving of its power. I know Ron and John wanted the heart of the film to be their father-daughter relationship, so I do wish they’d spent more time on Ariel and Triton as they reflected on how they see view other and making their respective journeys toward reconciliation even more fleshed-out and fulfilling.

You make a very good point. I’ve seen it argued that Triton goes through much more of an arc than Ariel does in this version of the story. It does make one realize perhaps there needed to be a scene between Ariel going off to see Ursula and Triton’s sudden reappearance at the climax where he’s roaring to his soldiers/servants about how they need to keep searching to find Ariel but when he’s alone he goes quiet and sad, saying to himself it’s so he can apologize.

I’ve never heard about any cut or unproduced scenes for this film. Could something like that have originally been planned?

Two side notes:

— A few years previous Disney financed the mermaid comedy “Splash” and released it under their new Touchstone label. That propelled Tom Hanks and director Ron Howard into the big leagues. Did the “Little Mermaid” crew look at that for ideas and/or things to avoid?

— “The Little Mermaid” went straight from theaters to video, the first Disney animated feature to do so — but still had a theatrical re-release later as a counter to Bluth’s “Anastasia”. I remember seeing a small sign in a local video store and suspecting it was bootleg, knowing how Disney usually worked.

AND, right after Disney’s own Hayley Mills left Disney, she voiced Rankin-Bass(Videocraft Ltd.) blonde (like her), no name Little Mermaid in their all-Hans Christian Anderson/Holywood/New York star THE DAYDREAMER, released, back in 1966! Also an odd thing, both Ariel and Thumbelina,voiced by another teen starlet outta the mid 60s, Patty Duke, had the same voice in their revivals, JOdi Besnon (and Duke’s own sitcom brother Paul O’Keefe played the title DAYDREAMER characterr.Hmmm..Isn’t it cozy.Anyone care to do an article on the above here..??)

Michael, in your book DRAWN TO GREATNESS: DISNEY’S ANIMATION RENAISSANCE (plug), you quote from interviews you conducted with John Musker, Ron Clements, Glen Keane, and other key figures. Would it be possible to post transcripts of these interviews in this column? I’m sure they contain a lot of information that’s never been published elsewhere.

Paul, thank you so much for the plug! … and for the idea for future articles!

There’s one thing that I feel like was missing in the article and that is the film getting inducted into The Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 2022 which I consider the highest regard for an American feature film.

The Library of Congress’ National Film Registry is totally meaningless.

Its idea of not making commercial modifications to a film once it has been inducted is trash.

Long after its induction, Fantasia has had Deems Taylor’s voice dubbed by Corey Burton on all officially released prints.

Movie vandalism.

I consider it to be more of an honors list, to be honest.

The idea is that the copy archived in the Library is the original version. There is no mandate to the owner that they can’t continue to fiddle with and release their own revisions.

My understanding is that the original audio for Deems Taylor’s introductions is largely deteriorated to the point of being unsalvageable or completely lost. Should the LoC not induct a movie for which some small part of the original release is unavailable? Would you have preferred that Disney just leave out the excised Taylor footage in current releases rather than relying on Burton’s attempted re-creation of the audio?

Stop with one of the internet’s favorite topics – fake lost media.

There are still heaps of prints around using the original audio.

The problem appears to be they can’t use the original source material to try and recreate 11.1 triple surround Atmos nonsense to a film which was never made that way.

With the exception of the discussion on soundtrack, most of his dialogue is merely him talking to the camera, and with little background noise.

Deems Taylor in SD and the rest in HD would have been a far superior option.

I wouldn’t call the live action remake of Little Mermaid to be successful in all regard. It will not be well remembered, even if it did technically make a profit.

I should mention this wasn’t the first time that a version of “The Little Mermaid” had a happy ending. Classic Illustrated’s spin-off series, Classic Illustrated Junior print an issue with the story in 1956. Because this was geared to younger readers (and the fact that the Comic Code Authority was already in effect by this point), the story’s bleak ending was replaced with a happier ending where the mermaid unites with the princes and loses the pain she had in her new legs thanks to the use of a MacGuffin in the form of seashells. Needless to say, this wasn’t as meaty as the climax of the 1989 animated feature film adaption.