NOTE: This is part 2 of our three-part Monday series on the earliest animated features ever created. To read Part 1 click here. Part 3 will conclude this series next week.

Around 1916, the producer Federico Valle discovered in the press the vignettes of twenty-year-old Quirino Cristiani, another Italian (arrived to Argentina at the age of four) and decided to summon him to his studios.

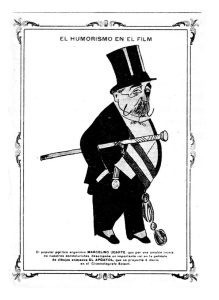

Valle had in mind the usual “lightning sketches”, short cartoons showing the artist’s hand in the act of producing an onscreen illustration, usually related to some current topic. But he also wanted something more. He gave to his young employee Émile Cohl’s Les allumettes animées (1908), one of the first animated films, to let him study the new technique. Cristiani adopted Cohl’s idea, albeit with a couple of variations. If the Frenchman’s animations showed a white line on a black background (a product of directly copying the negative), Cristiani would draw “in negative”, to obtain a black line on a white background. To this, he added the possibility of animating two dimensional figurines made of cut-out cardboard and joints fixed by means of threads (invention registered under his name at the Argentine Patent Office with the number 15,498). That year, the newsreel “Actualidades Valle” premiered an episode that included a minute of Cristiani’s cartoon whipping Governor Marcelino Ugarte. It was called La Intervención en la provincia de Buenos Aires.

The Arrival of the Apostle

The success was surprising, so much so that Valle decided to use Cristiani in a new project: an animated feature film, something never done before. He thought of combining the talents of the most popular cartoonist in Buenos Aires, Diógenes Taborda, with those of the playwright Alfonso de Laferrère, together with Andrés Ducaud, who worked in his company as “Chief Animator” (let’s pay attention to this fact). Cristiani, with his innovative animation technique, would function as the axis connecting the work of these men. And the theme would be, as always, a political satire. The Argentine president, Hipólito Yrigoyen, seemed to be the perfect target. What was needed then was a theatre willing to exhibit the result. Businessman Guillermo Franchini (the man who introduced the cocktail lounge as a novelty in Buenos Aires and owner of the “Select Suipacha”) came with the money.

The plot of El apóstol (The Apostle), the film that came out of all this, is more or less known: Yrigoyen, alias “The Apostle”, falls asleep in his humble cot and dreams. In his dreams he sees the city of Buenos Aires, and not in a good light. Fed up with so much corruption and vice, he travels to Olympus, asks for and obtains the thunderbolts of Jupiter and throws them furiously on the city. After the destruction of Buenos Aires, Yrigoyen wakes up. It had all been a dream.

Taborda defined the general style of the film, providing what today we would call the “model sheet” of Yrigoyen and his ministers. Well informed about the cartoons of his time (in a 1917 interview he specifically quotes John R. Bray’s The Artist’s Dream), Taborda did not produce any animation, nor was he in a position to do so, considering that he had to deliver his regular quota of material as a graphic star of the newspaper Crítica.The “Mono” Taborda, in spite of being the only cartoonist who have a street with his name in Buenos Aires (a reminder of the popularity he enjoyed at the time of his early death in 1926) and of being the mentor of Dante Quinterno, of Patoruzú’s fame, needs today a clarification, even in Argentina. It seems that Natalio Botana, the director of Crítica, managed to incorporate him into his newspaper by force. According to Botana’s son, Taborda lived at ease doing street caricatures for five pesos and betting with the unwary at billiards, until he fell into the clutches of a Spanish specialist in the field and the resulting debt forced him to take a stable job. In any case, Taborda lacked the discipline or the time to do the countless drawings demanded by an animated film.

This did not represent a problem for Valle’s draftsmen, quite the contrary: Cristiani indicates in his account that Taborda’s designs were too detailed and difficult to animate. He had to simplify them, a process for which he had the graphic star’s approval, “as long as his name was on the screen”.

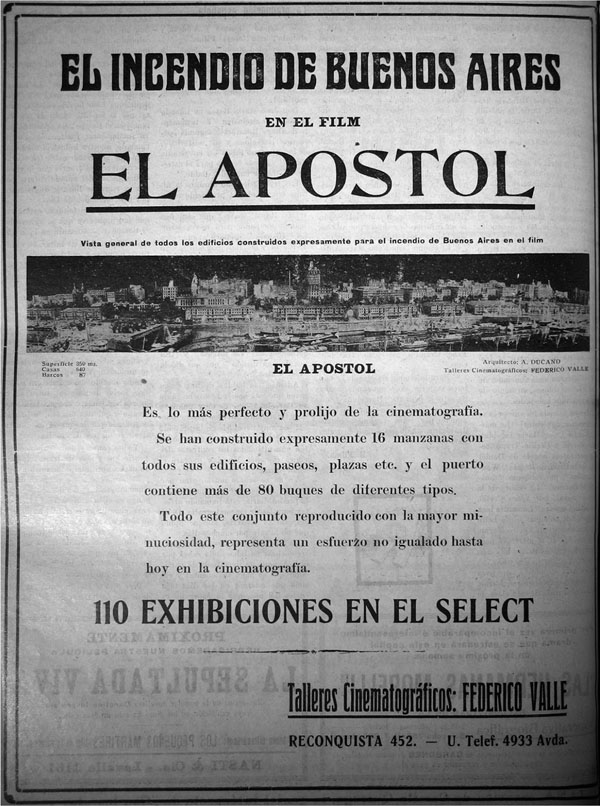

Valle mentions as part of the team of animators the cartoonists Vicente Cáceres, Carlos Espejo and Manuel Costa, a fact corroborated by contemporary newspaper reviews. (Note: the only one of these cartoonists for whom I could get additional data is the Chilean Carlos Espejo, who in 1924 would make in his native country Vida y milagros de Don Fausto, a local adaptation of the American cartoon Bringing Up Father, by George McManus). The name of Andrés Ducaud, author of the fabulous ending of the film, in which a gigantic three-dimensional model of Buenos Aires, built by him, fell under the rays of the “apostle”, figures prominently.

According to Di Núbila, “Valle resorted once again to Ducaud’s patience and manual prodigies and commissioned him to reproduce the city in a gigantic maquette. The great French craftsman had to build hundreds of small buildings and dozens of cars and ships, in scale with reality. He did not protest; he only asked for time. And after a few weeks he showed, in the back of his house on Cabildo Avenue, the finished work. It raised exclamations of admiration. In that seven-meter wide maquette was Buenos Aires as it was, with its streets, avenues and squares, with the palaces of the Congress, the City Hall, the Waterworks Building, the Colón Teather, emerging towards the sky, with the old Customs House facing the river and also with the port, in whose docks more than eighty little boats were rocking”.

Bendazzi speaks of several models, separated by scenes, with one of the city center that included traffic signs, illuminated signs, and moving automobiles. “The scene was then photographed using horrible special effects, which were probably flames superimposed with a red tone (for fire) and a blue tone (for flooding).”

The obvious fact to be deduced from this (though rarely mentioned) is that, as the final sequence of El apóstol was done in a completely different technique than Cristiani’s usual one, it is likely that it was not animated or directed by the Italian cartoonist. In fact, the inference that Cristiani is the sole director of the film is exclusively modern and does not emerge from the reviews of the time or the advertising (which, instead, emphasized Ducaud’s sequence); although, on the other hand, there’s no reason to doubt that it were Cristiani’s graphic and technical contributions – added to his “synthetic” humor – the keys to the film’s success.

Detail of the model of the city of Buenos Aires built by Ducaud

El apóstol premiered on November 9, 1917 at the “Select Suipacha” and the newspapers celebrated it rabidly, pondering its 58,000 frames (one hour and ten minutes, according to the ratio of frames per second of silent films), “the freshness and originality of its plot” and its technical quality, “which was not in detriment to American productions.”

Di Núbila points out that despite its initial success, “El apóstol did not achieve a transcendence that compensated for the effort it had demanded.” Bendazzi disagrees with this opinion, taking into account that the film’s local subject prevented any exportation and that it had been conceived to be shown in a single theater. In any case, the film remained in exhibition for more than six months, first in a double bill, and then shown as the only attraction. It was screened up to seven times a day (which indicates that several copies had to be produced, an encouraging fact for those who dream of finding one of them). In any case, the economic results were good enough for Franchini and Valle to decide to produce another similar feature.

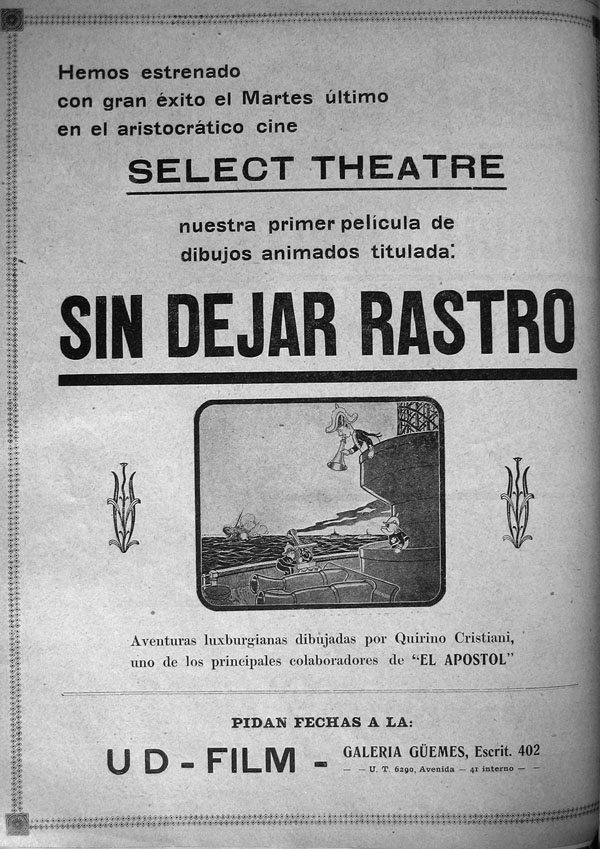

The second one: “Sin Dejar Rastro” (Without a trace)

However, someone went ahead of them. The film was called Sin dejar rastro and was again directed by Cristiani, appealing to his usual technique. Very little is known about this second film, except that it was premiered around mid-1918 at the “Select Theatre” on Lavalle Street, had a script by José Bayoni and was financed this time by Della Valle y Fauvety, president of the company that owned the “Gath & Chaves” department store (through the improbable “U D Film”), with no artistic interference from hands other than those of the cartoonist. Attention: its status as a feature film seems to be endorsed only by the memory of its author.

Its plot was based on a diplomatic incident during the First World War (the sinking of the Argentine schooner “Monte Protegido”, due to a German torpedo) and that was precisely the reason for its rapid confiscation by the national authorities, who wished to avoid an escalation of the issue in public opinion. Sin dejar rastro it was exhibited only one day and disappeared honoring its name, a joke that no historian ever failed to exploit. But an interesting fact is implicit here: Valle does not seem to have had any participation in it as producer. Cristiani had cut loose himself. He was not the only one.

Media advertising of “Sin dejar rastro”. The central vignette is the only image preserved from the film.

Three: Abajo la Careta (Down with the mask)

Because that is precisely what Ducaud, the other important collaborator of El apóstol, did next. His film Abajo la careta or La república de Jauja was a feature film made with animated cartoons, started immediately after Valle’s production and finished quickly enough to be screened on March 18, 1918 at the “Grand Splendid”, the “Esmeralda”, the “Callao” and the “Petit Palace”, according to historian Jorge Miguel Couselo. It was presented exclusively as a Cine Gráfico production, by “Ducaud & Co”. The name of other collaborators is unknown. The brief advertisements of the film only stated that “intellectual minds collaborated to make this film, together with the best artists of the capital of the country”, providing some reproductions of the drawings that only bore the signature of Ducaud.

Cast of “La república de Jauja”, drawn by Ducaud.

It seems that the film, in this case, was a satire against the conservative government of the old oligarchy prior to Yrigoyen. There is no doubt that La república de Jauja, with its 62,000 drawings advertised in the media (and therefore of a similar or longer duration than El apóstol), followed the structure of its predecessor, its taste for caricatures and the meticulousness in the portrayal of political personalities and celebrities. The subject matter, written by an unknown author, abandoned the previous allegory in favor of anecdotes, showing “the intrigues of political factions”, along with easily identifiable buildings, bustling streets and panoramic views of Buenos Aires (again showing Ducaud’s architect’s hand). The film as a whole seemed less agile and tolerable than its predecessor, if we take into account the journalistic opinion of the time (La Película magazine), which accused it of “possessing the vice of lushness, of the superabundance of types in action; too much visual field has been wanted to cover and such ideal extension overwhelms the spectator… and there is no imagination, however powerful it may be, capable of encompassing in thought the synthesis of a vast theme such as the film proposed”.

Cast of “La república de Jauja”, drawn by Ducaud

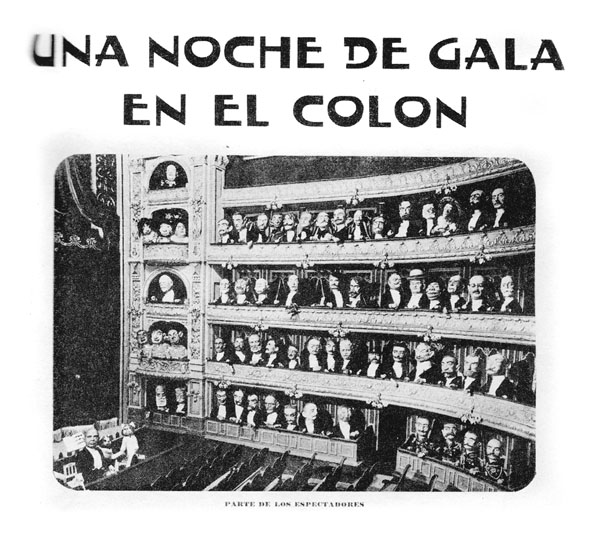

Four: Una Noche de Gala en el Colón (A Gala Night at the Colón)

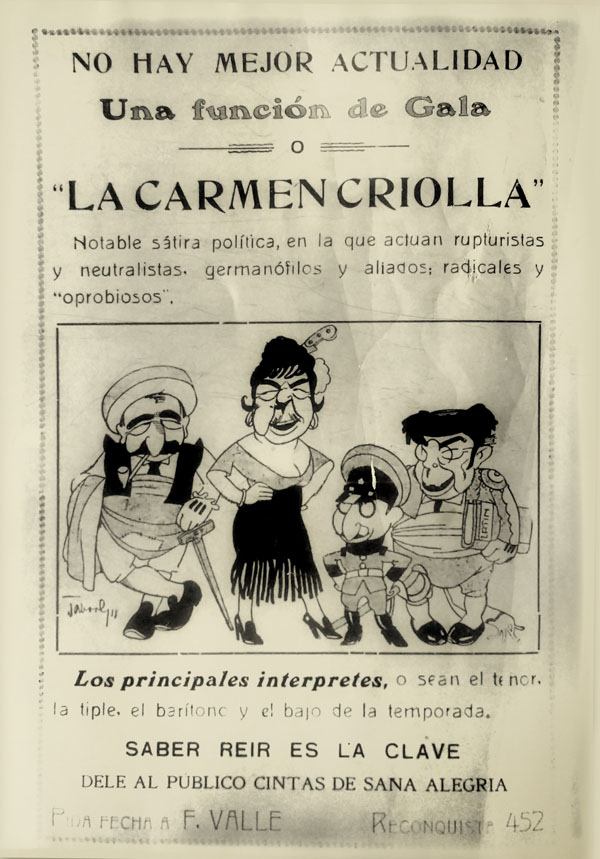

The success of their first feature propelled Valle and Franchini’s attempt to make a second one: Una noche de gala en el Colón or La Carmen criolla. Both Valle, who produced it, and Cristiani, who did not participate in the project and remembered it only as a spectator, had no doubt that it was a feature film, agreeing on this with Di Núbila, Couselo and Bendazzi. IMDB (that pearl of human creativity) instead suggests a more modest ten minutes, but without providing any source to back up the data.

Advertising for “Una noche de gala en el Colón”

According to Di Núbila: “The theme was again political, with satirical darts aimed at Yrigoyen. The action took place at the Teatro Colón on a gala night, attending a performance of Carmen”.

As had happened with El apóstol, the film was divided into two parts, each one made using different techniques. The first block, starring stop-motion animated dolls, began with the great figures of the political and social life of Buenos Aires arriving at the theater, whose orchestra was composed of cats. The second part consisted of a drawn cartoon section showing the performance of the opera, in which President Yrigoyen played the role of Carmen, along with his ministers and friends as part of the cast. The drawn opera interacted with the photographed dolls, acid commentators of what was seen on stage. Towards the end, the inmates of Villa Devoto prison burst in, invited to participate in the evening. The session ended in general disbandment.

Movie poster of “Una noche de gala en Colón”, showing Taborda’s designs for the cartoon part. Courtesy of Museo del Cine.

The volumetrically rendered political caricatures foreshadow the ones that the British TV show Spitting Image would produce some seventy years later. Their design was once again in the hands of Taborda, who was in charge of designing both the ones for the drawn section and those that would serve as models for the dolls. Based on his drawings, a sculptor made plastine (sic) models and after slight corrections, the final molds were prepared.

detail of the volumetric caricatures of the stop-motion animated section.

Several heads of the same doll were made, with different expressions and lip positions so that they would appear to be talking if photographed in a particular order, and the whole was then painted.

detail of the volumetric caricatures of the stop-motion animated section

Ducaud was in charge of preparing a meticulous reproduction of the Colón, and he reconstructed, in miniature, the main hall and the interior of the theater, with its boxes, stalls, stages and decoration in proportion to the size of the puppets.

detail of the volumetric caricatures of the stop-motion animated section.

The filming was done frame by frame, and as it usually happens in these cases, the complications increased in direct relation to the number of “actors” in front of the camera. At some point, there were more than a hundred dolls dancing in unison on the screen.

The result was “more of a curious experiment than anything else,” or so they say. Di Núbila, who implies in his book that the direction of the set went through Valle himself with a generous hand lent by Ducaud, reports that “Una noche…” did not please the public, perhaps because it lacked the effective simplicity of Cristiani’s work. For the latter, the film was not successful “because the movement of the characters was imperfect, because it was not funny, and because the subject matter was not very interesting”.

overall shot of the stop-motion animated section.

In short, Valle produced two of the four films we refer to (El apóstol and La Carmen criolla), while Ducaud and Cristiani produced the other two on their own. Both Ducaud and Cristiani would work intermittently for Valle, who also had journalists and other part-time creators on his staff of writers. The exclusivity of his employees was not a desirable or possible item for the Italian, who on this point was at the antipodes of the big producers in the USA.

In any case, the production of Argentine animated feature films seems to have ended abruptly after 1918. Enabled by the success of El apóstol, the three productions that followed (in the same year) did not achieve sufficiently encouraging results to exploit the novelty further… at least until 1931, when Cristiani returned with a new experiment. But this story will be left for the next installment.

Next Week: Part 3, our conclusion.

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Argentina’s policy of neutrality during World War I greatly benefited the country’s economy. But at the same time, President Yrigoyen had to walk a political tightrope between the commercial sector, which wanted Argentina to enter the war on the side of the British, and the army, which wanted to enter on the side of the Germans. So it’s understandable that his government would confiscate “Sin dejar rastro”, however repugnant from a free-speech standpoint. Has posterity recorded the opinion of President Yrigoyen or his ministers on “El apostol” (assuming any of them even saw it)? The fact that it was shown so many times, over such a long period, suggests that he was at least a good sport about it.

When you say that the orchestra musicians in “La Carmen criolla” were portrayed as cats, do you know whether they were cat dolls, drawings of cats, or (shudder) some form of animated novelty taxidermy along the lines of what Starevich used to do with all those insects?

Hi, thanks for your interest. Yrigoyen was a legitimated target and I think he should be the most caricaturizated argentine president ever. He was known for his tolerance to his numerous “portraits” (as it was the XIX century president Sarmiento, often iracund on other fields). “Sin dejar rastro” was probably confiscated not for its caricatures but to simply avoid the subject matter.

In regard to the cats, you can spot them on the big photo at the begging of the four section. Luckily, no cats were harmed.

As additional detail: the “great figures” of the “La Carmen Criolla” covered a big arch of the cultural life of Buenos Aires. From the socialist politicians Alfredo Palacios (the moustached man) and Juan B. Justo -they could be seen in the third photo- to the “Negro” Raul, an afro argentine dandy who is in the middle of the two. Incidently, is to be noted that the caricature of Raúl is based on an particular individual and not in a broad “type”.

Thanks for pointing out those cats, Lucas. I’m travelling at the moment, and I overlooked that detail reading the article on my phone. Is the orchestra conductor meant to be a caricature of an actual person?

Yes, they all are supposed to be, even though most of the references were lost in time. We can deduce the players in the most famous or caricatured cases (such as socialist leaders, Mr. Raul or some conservative politicians). There are many inside jokes in any of these four films, and it would even seem -as far as we are given to assume, because none of them has survived- that this kind of humor is central to their plots: in almost all cases they play with what the viewer should already know.