Subtlety doesn’t seem to have been Pat Sullivan’s strong suit. When attempting to impress Adolph Zukor with how badly he needed to retain the rights to Felix the Cat, Sullivan reportedly urinated on the man’s desk. Raised in a working class neighborhood of Sydney, Australia, Patrick O’Sullivan made his way to England as a young man. He often slept on the banks of the Thames River, earning what he could by selling sketches, and the occasional published cartoon. Pat dropped the O’ from his last name to do a bit of singing and hoofing in London dance halls, then tried his hand at being a film exhibitor, When that failed, Sullivan took a job tending mules being sent across the Atlantic. On one voyage he jumped ship in the port of New York.

Subtlety doesn’t seem to have been Pat Sullivan’s strong suit. When attempting to impress Adolph Zukor with how badly he needed to retain the rights to Felix the Cat, Sullivan reportedly urinated on the man’s desk. Raised in a working class neighborhood of Sydney, Australia, Patrick O’Sullivan made his way to England as a young man. He often slept on the banks of the Thames River, earning what he could by selling sketches, and the occasional published cartoon. Pat dropped the O’ from his last name to do a bit of singing and hoofing in London dance halls, then tried his hand at being a film exhibitor, When that failed, Sullivan took a job tending mules being sent across the Atlantic. On one voyage he jumped ship in the port of New York.

Sullivan was fired by Barré within a year for incompetence, likely due to alcoholism. When William Randolph Hearst raided Barré’s staff in 1916 to form IFS he also invited Sullivan, who declined the offer and opened his own studio. Pat Sullivan Productions made arrangements with producer Pat Powers, a founder of the Universal Motion Picture Manufacturing Company.

At that time Pat Powers held rights to make NERVY NAT HAS HIS FORTUNE TOLD, a live-action short based on James Montgomery Flagg’s comic-strip. Flagg is better remembered for his “Uncle Sam Wants You” recruitment poster in the upcoming war. Sullivan put together a cartoon film titled NERVY NAT written by Flagg for Powers to release. Powers arranged for Sullivan’s artwork to be photographed at Universal’s Fort Lee facility.

Otto Messmer

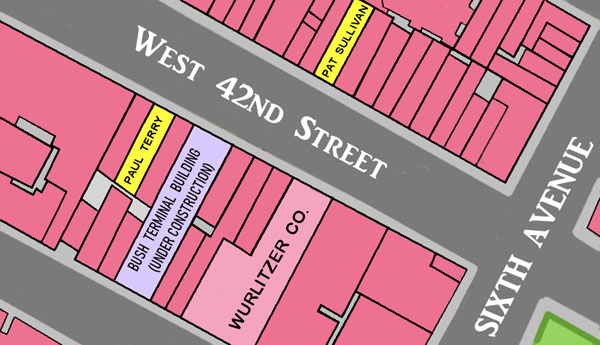

Pat Sullivan Productions worked out of an apartment near Bryant Park at 125 West 42nd Street, right across the street the Wurlitzer organ company. On that same block, a few doors over, was Paul Terry’s 1916 studio at 138 West 42nd Street (not connected to the New Amsterdam Theater, which is a block to the west). The building where Terry rented space would either be torn down, or incorporated into the Bryant Theater as a rear entrance five years later.

Several artists jammed into Sullivan’s apartment, He got himself arrested for statutory rape with a teenage girl from the neighborhood. Sullivan quickly married Marjorie Gallagher, one of his inkers, to prove he’d reformed. A good lawyer and a sympathetic judge led to a nine month prison sentence. During that time Otto Messmer was drafted and sent to the frontline trenches in France where he saw war close up.

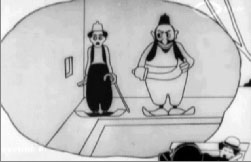

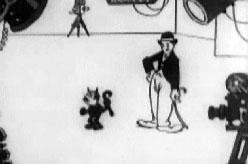

Otto Messmer returned home to rejoin Pat Sullivan Productions in that same little apartment/studio near Bryant Park, just the two of them now. They did a series of Charlie Chaplin cartoons. The first one was patriotic, to mark America’s recent victory against Germany: OVER THE RHINE WITH CHARLIE. Without permission they made eight Charlie cartoons, and soon had a deal with John Bray’s Studio to distribute through Paramount Pictures.

Otto Messmer returned home to rejoin Pat Sullivan Productions in that same little apartment/studio near Bryant Park, just the two of them now. They did a series of Charlie Chaplin cartoons. The first one was patriotic, to mark America’s recent victory against Germany: OVER THE RHINE WITH CHARLIE. Without permission they made eight Charlie cartoons, and soon had a deal with John Bray’s Studio to distribute through Paramount Pictures.

In 1919 Sullivan and Messmer created a trilogy about a detective named HARDROCK DOME. John Bray released them. When Bray partnered up with Sam Goldwyn he broke off relations with Paramount. Sullivan seized that opportunity to provide cartoons directly to Paramount for their screen magazine. One of those films was FELINE FOLLIES with a cat named Master Tom, who tested well.

A Paramount executive renamed the cat “Felix” and ordered a series. Those cartoons alternated in Paramount reels with ones about gray SCAT THE CAT made by Frank Moser. Felix the Cat’s character caught on like wild-fire. Prosperity got them out of that cramped apartment. In 1920 Pat Sullivan Productions moved to the fourth floor of the Lincoln Arcade Building on the corner of 66th Street, where Broadway crosses Columbus Avenue.

Marjorie Sullivan worked there alongside her husband, though he did little actual work. Pat’s lawyer from the rape trial handled contracts and business details. Otto Messmer ran production. The studio did nothing except the FELIX THE CAT series. Pat Sullivan, having struck gold, stayed drunk and chased women. Attempting to exploit the success of Felix, John Bray cut a deal with William Randolph Hearst to revive KRAZY KAT. It didn’t work. Felix had an inexplicable appeal. The fan-base for that little black cat spread worldwide.

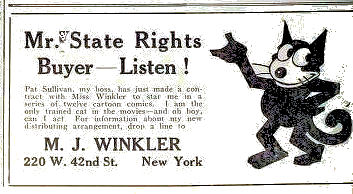

When Paramount announced it planned to end its screen magazine, Sullivan feared he’d lose rights to the character of Felix. That’s how he ended up pissing on Adolph Zukor’s desk. Rather than deal with the lunatic, Zukor gave him the cat. Sullivan took Felix to Margaret J. Winkler, a cartoon distributor who’d been an assistant to one of the Warner brothers. The first effort for Winkler was FELIX SAVES THE DAY, done entirely by Otto Messmer. The film mixes live footage with animation so that Felix rides in alive-action taxi cab. Otto Messmer made good use of tight budgets.

When Paramount announced it planned to end its screen magazine, Sullivan feared he’d lose rights to the character of Felix. That’s how he ended up pissing on Adolph Zukor’s desk. Rather than deal with the lunatic, Zukor gave him the cat. Sullivan took Felix to Margaret J. Winkler, a cartoon distributor who’d been an assistant to one of the Warner brothers. The first effort for Winkler was FELIX SAVES THE DAY, done entirely by Otto Messmer. The film mixes live footage with animation so that Felix rides in alive-action taxi cab. Otto Messmer made good use of tight budgets.

Hal Walker, who’d done some training with Raoul Barré in the Bronx, was hired as Messmer’s assistant. Cels were rarely used at either Barré or Sullivan’s studios unless an effect was needed. Barré had developed what he called the Slash System. Finished drawings were done on paper that was cut to fit empty spaces against the background drawing. Beside the cost of cels being avoided, so was the expense of taking out a license with the Bray-Hurd Trust.

Sullivan merchandised the Felix image for dolls, postcards, and ceramic toys. Hearst’s King Features Syndicate took advantage of the craze, licensing production of dolls of Krazy Kat. But John Bray’s company ended their involvement with that cartoon series. There was no competing with Felix. Studying Charlie Chaplin for those earlier films influenced Otto Messmer immensely, adding nuance to Felix’s personality. Felix could raise an eyebrow and get a laugh. LIFE Magazine’s respected film critic declared Felix the Cat to be among the top movie comedians of 1922. The cartoon FELIX IN HOLLYWOOD showed him hobnobbing with other stars, Chaplin among them.

Sullivan merchandised the Felix image for dolls, postcards, and ceramic toys. Hearst’s King Features Syndicate took advantage of the craze, licensing production of dolls of Krazy Kat. But John Bray’s company ended their involvement with that cartoon series. There was no competing with Felix. Studying Charlie Chaplin for those earlier films influenced Otto Messmer immensely, adding nuance to Felix’s personality. Felix could raise an eyebrow and get a laugh. LIFE Magazine’s respected film critic declared Felix the Cat to be among the top movie comedians of 1922. The cartoon FELIX IN HOLLYWOOD showed him hobnobbing with other stars, Chaplin among them.

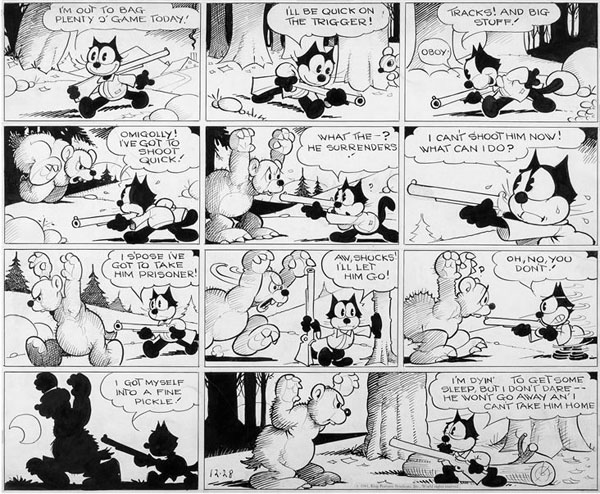

Sullivan’s studio put out a Felix the Cat newspaper strip drawn by Otto Messmer. The studio moved again, this time to a nice space at 47 West 63rd Street between Broadway and Central Park. It was a long narrow loft. A row of animation desks were built against one wall, and a partition set up for Sullivan’s office along the other. A section in the back housed a camera.

Sullivan’s studio put out a Felix the Cat newspaper strip drawn by Otto Messmer. The studio moved again, this time to a nice space at 47 West 63rd Street between Broadway and Central Park. It was a long narrow loft. A row of animation desks were built against one wall, and a partition set up for Sullivan’s office along the other. A section in the back housed a camera.

Marjorie Sullivan was allowed to retire to a life of ease. All employees from there on would be men. The staff grew to about ten people. Otto Messmer kept the Felix assembly line running, over-seeing every aspect. He’d often be talking with one of the animators while simultaneously counting camera clicks from the other room to determine timing of a scene.

Messmer streamlined production. Drawings in a Felix cartoon were simple. Gray-tones were omitted for a stark black-on-white approach. Those who would be known as inkers in other studios were called tracers. They outlined drawings on a fresh page with ink. So much ink was used to fill in each Felix that opaquers were dubbed “blackeners”. George Cannata, a short, feisty fellow from New Jersey was hired as a blackener in 1923. A song titled FELIX KEPT WALKING, sing by Clarkson Rose, became popular.

Stories in a Felix cartoon were rudimentary, often involving a quest of some sort, maybe for food or shelter, or even a bit of knowledge. Messmer favored plays on words. In one cartoon Felix helps a boy find out what makes the Moon shine and ends up drinking bootleg liquor, known as “moonshine”. Ideas spewed forth from Messmer. No scripts were written. He’d pick a theme for a film and tell each animator the basics of the scene he wanted, and left them to work. Notes were made in a drawings margin to let the cameraman know how many exposures were needed. Messmer would be everywhere at once while drawing his own scenes as well. In places a finished film’s continuity seemed disjointed, but audiences didn’t care. The character’s popularity swelled. Pat Sullivan carried on in the press as if it was all his doing.

Stories in a Felix cartoon were rudimentary, often involving a quest of some sort, maybe for food or shelter, or even a bit of knowledge. Messmer favored plays on words. In one cartoon Felix helps a boy find out what makes the Moon shine and ends up drinking bootleg liquor, known as “moonshine”. Ideas spewed forth from Messmer. No scripts were written. He’d pick a theme for a film and tell each animator the basics of the scene he wanted, and left them to work. Notes were made in a drawings margin to let the cameraman know how many exposures were needed. Messmer would be everywhere at once while drawing his own scenes as well. In places a finished film’s continuity seemed disjointed, but audiences didn’t care. The character’s popularity swelled. Pat Sullivan carried on in the press as if it was all his doing.

Trouble brewed between Sullivan and Margaret Winkler. He proved to be a quarrelsome drunkard, and she married a domineering booking agent named Charles Mintz who sought control of her business. Felix the Cat merchandise continued to sell. One of Margaret Winkler’s other clients, a fellow named Disney, used a black cat character in his cartoons that looked a lot like Felix. Pat Sullivan picked a fight about that.

New York Globe cartoonist Jack Carr joined Sullivan’s studio in 1924. So did Bill Nolan, who redesigned Felix to make him cuter. Production increased to twenty-one films a year. The continuity improved, and gray-tones appeared more often, giving the films some depth. Felix cartoons ranged in subject matter: that clever little cat might be on a golf course, hunting bear, or following his little blonde sidekick to school. Felix travelled by various creative means to Egypt, Japan, Russia, and even Story Book Land. One film was about evolution, another about union strikes. People loved it. Pat Sullivan and his wife went to England. The British press embraced Sullivan as a celebrity while he promoted his cartoons. Otto Messmer felt financially secure enough to marry his childhood sweetheart Anne Mason.

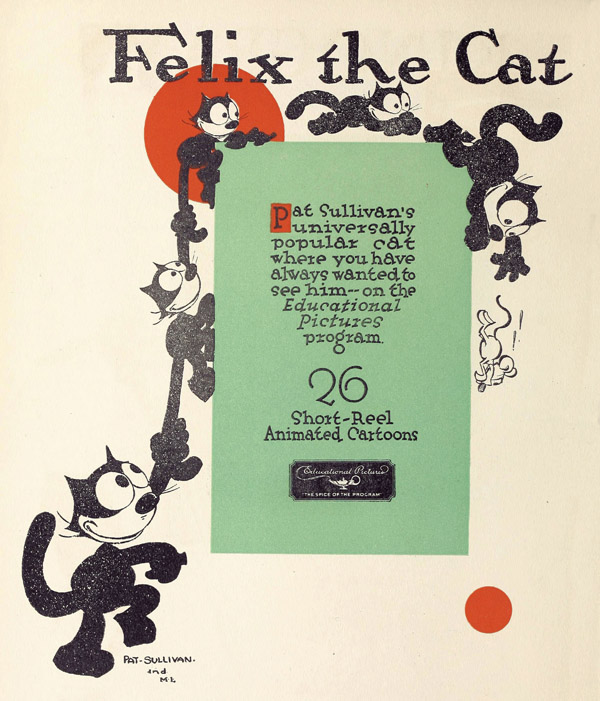

Pat Sullivan Productions and Margaret Winkler disputed their contract in court. Sullivan won the case and dismissed Winkler and Mintz as distributors in favor of Educational Pictures, who were affiliated with Fox Films. It was the Roaring Twenties, America’s postwar hurrah. College students danced the Charleston. Regardless of Prohibition, bootleg liquor flowed everywhere. Middle-class Americans had never experienced such an age of leisure before. The automobile industry prospered as more people bought cars. Sullivan licensed out the use of Felix in THE CAT AND THE KIT, an advertisement cartoon for automobile headlights manufactured by Thomas Edison’s company General Electric.

Pat Sullivan Productions and Margaret Winkler disputed their contract in court. Sullivan won the case and dismissed Winkler and Mintz as distributors in favor of Educational Pictures, who were affiliated with Fox Films. It was the Roaring Twenties, America’s postwar hurrah. College students danced the Charleston. Regardless of Prohibition, bootleg liquor flowed everywhere. Middle-class Americans had never experienced such an age of leisure before. The automobile industry prospered as more people bought cars. Sullivan licensed out the use of Felix in THE CAT AND THE KIT, an advertisement cartoon for automobile headlights manufactured by Thomas Edison’s company General Electric.

It’s been written that on a good day Bill Nolan could do around five hundred pose drawings. Otto Messmer was nearly as quick. Felix films were completed at an astounding pace for such a small group. Suddenly Bill Nolan left Sullivan’s studio to start his own in Long Branch, New Jersey with Margaret Winkler and Charles Mintz as producers. Nolan took Jack Carr with him. Nolan grabbed onto many elements of the Felix series for his KRAZY KAT revival. Vernon Stallings was brought in to replace Nolan.

About six years had passed since Charles Bowers drove Raoul Barré from the animation biz. Barré was hired by Pat Sullivan, who may have experienced some glee in having a man who once fired him under his thumb, but Otto Messmer loved having Barré around. As production increased they needed more blackeners and sixteen year old Al Eugster was hired. During 1926 production increased to a cartoon every two weeks. Burt Gillett, another alumnus of Barré’s studio, joined Messmer’s crew.

Aviation was an advancing field. Airplanes became larger and faster. Their range increased. When Charles Lindbergh undertook his well publicized non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927 Felix responded with NON-STOP FRIGHT, wherein the little cat flies across an ocean. A couple months later Ruth Elder set out to be the first woman to fly over the Atlantic. She brought a Felix doll along for good luck. LIFE Magazine ran an eight-panel cartoon exemplifying Felix as “the art of the motion picture”. Then sound came into the movies in 1927. The days of a pianist sitting in a theater playing accompaniment to films were over, distributors wanted sound product. That meant buying new equipment for the studio, as well as hiring voice-actors and musicians. Sullivan refused, arguing that part of Felix’s charm was that he never spoke. Why mess with a formula that had made Felix indisputably the most popular cartoon star in the world?

Sullivan didn’t plan on rocking the boat when things were going so smoothly. Raoul Barré retired from the business, returning to his native Canada to teach art in Montreal. It was a loss, but Messmer had developed a capable team of younger talent. Mexican born Rudy Zamora, with a year of training at Cooper Union, joined George Cannata and Al Eugster as a blackener. The trio would roughhouse in the break room. At the drawing boards they were all business. Despite an improving artistic quality, no one wanted silent cartoons. Fox pulled out of distribution and Sullivan ended up dealing with First National Pictures, a Warner Brothers subsidiary that made low-budget movies. It was a drop in stature. Some of that year’s Felix releases were reissues, while a few interesting new films got made.

These later Felix cartoons are the most surreal. Messmer’s draftsmanship and sense of composition had improved so his characters filled the screen. Bold use of shadows added stark atmosphere. Only sixteen were made in 1928. The public, unaware of what went on behind the scenes, still adored that little black cat. When the Radio Corporation of America did a test broadcast of an experimental medium called television that year they used an image of Felix.

These later Felix cartoons are the most surreal. Messmer’s draftsmanship and sense of composition had improved so his characters filled the screen. Bold use of shadows added stark atmosphere. Only sixteen were made in 1928. The public, unaware of what went on behind the scenes, still adored that little black cat. When the Radio Corporation of America did a test broadcast of an experimental medium called television that year they used an image of Felix.

Production of Felix cartoons dropped to a dozen in 1929, but they had some sound, and fifteen old cartoons were reissued with shoddy soundtracks. First National no longer distributed them. Jacques Kopfstein, former production manager at Bray Studios, released Felix films through his Copley Pictures Corporation. People didn’t like these new ones.

Lay-offs occured at Sullivan’s studio. With little else to do Al Eugster, Rudy Zamora and George Cannata all worked on a special project in 1929. The New York animation community had decided to host a dinner honoring Winsor McCay. Personnel from several studios pitched in as volunteers to make a pornographic cartoon titled EVEREADY HARTON IN BURIED TREASURE to be shown at the event. Film labs in America wouldn’t develop it, so the porn cartoon was processed in Cuba.

Clearly Prohibition didn’t work, because the animators got good and drunk at Winsor McCay’s dinner. When McCay was asked to speak, he took full credit for giving them all an art form, and berated the other animators for reducing it to nothing more than a mere trade. McCay wasn’t wrong, but he was being unfair to a lot of the men present. Many of them sincerely wanted to take their work to the level of art, and wished they had McCay’s financial resources to do as they pleased. McCay had put out a film every few years, at his own pace, for a brief period. He hadn’t released one in nearly eight years before his speech. These guys were down in the trenches sweating out a cartoon per month for corporate bosses who wanted fast, not fancy. They did it because they loved doing it, and they wanted to make better cartoons. Better than circumstances permitted.

Clearly Prohibition didn’t work, because the animators got good and drunk at Winsor McCay’s dinner. When McCay was asked to speak, he took full credit for giving them all an art form, and berated the other animators for reducing it to nothing more than a mere trade. McCay wasn’t wrong, but he was being unfair to a lot of the men present. Many of them sincerely wanted to take their work to the level of art, and wished they had McCay’s financial resources to do as they pleased. McCay had put out a film every few years, at his own pace, for a brief period. He hadn’t released one in nearly eight years before his speech. These guys were down in the trenches sweating out a cartoon per month for corporate bosses who wanted fast, not fancy. They did it because they loved doing it, and they wanted to make better cartoons. Better than circumstances permitted.

Pat Sullivan’s delay in converting to sound backfired and by 1930 his studio was broke. There was still some money coming in from merchandising, but Mickey Mouse toys outsold Felix the Cat. Pat Sullivan bragged to reporters about moving his studio to Hollywood. Jacques Kopfstein announced he’d be releasing a series of twelve HYPO THE MONK cartoons from Sullivan, but nothing came of all that. Blue Note Records later operated from the building where Pat Sullivan Productions had been.

New York City’s annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in 1931 featured a huge hot air balloon of Felix. Two years later Sullivan attempted to start things up again to make sound cartoons. Those plans were interrupted when Sullivan’s wife Marjorie fell to her death from a hotel window in Manhattan. Pat Sullivan died of heart failure shortly afterwards. Both Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and RKO Pictures contacted Otto Messmer about continuing the Felix series with them, but he didn’t own the character. Despite prior promises from Sullivan, Otto Messmer got shafted when all rights to Felix went to Pat Sullivan’s nephew in Australia. Sullivan’s lawyer discussed a possible production arrangement with Pat Powers, but that fell through.

The year after Pat Sullivan’s death director Komatsuzawa Hajime made a cartoon predicting the United States would soon invade his home country of Japan. The evil America was symbolized by an aggressive Mickey Mouse. As testament to the cross-cultural love for Felix, Hajime used that little black cat to represent one of the heroic Japanese people.

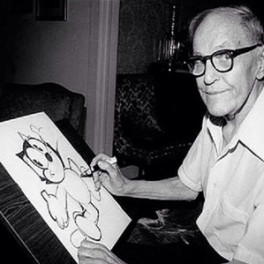

Messmer in later years

By 1940 Doug Leigh’s shop was at 630 Fifth Avenue. In 194i they made animated segments for NBC’s New York weather broadcast. The segments featured the lamb mascot of Worsted Mills, who sponsored the broadcasts. Also in 1941, Leigh and Messmer made the first television commercial in the U.S. for the Bulova Watch Company.

During World War Two air raid blackouts hurt Doug Leigh’s business. Messmer took a job with Famous Studios until war’s end, then returned to Leigh. During the 1960s Messmer ran his own little studio a couple doors over on the third floor of 530 Fifth Avenue. Many feel that he was the true creator of Felix, cheated of his property by the pernicious Pat Sullivan. Messmer simply recognized the Sullivan had been a troubled individual, and left it at that.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

Sydney’s inner suburb of Paddington was indeed a densely-populated working class slum when Pat Sullivan was growing up there in the late 1800s. It even had an outbreak of bubonic plague around the turn of the last century. But today it’s a trendy and very expensive place to live, though just as densely populated as ever. Don’t even think about driving there; you’ll never find a parking spot.

When Sullivan was hired by Raoul Barre, there were already two Australians working at the studio, Alec Laing and Harry Julius. Both of them, like Winsor McCay, had started out as lightning sketch artists (Julius was performing professionally at age nine!), and both had served in the Boer War as teenagers. Julius later returned to Australia and ran a film studio in Sydney that made animated advertisements and industrial films. I don’t know what happened to Laing.

Several years after Sullivan died, his friend Kerwin Maegraith recounted a conversation between Sullivan and his wife, ascribing an Australian origin to Felix’s name. “Australia Felix”, Latin for “happy Australia”, was a commonly used expression to describe Australia as “the lucky country”. There was also a boxer named Peter Felix, who was the Australian heavyweight champion when Sullivan was growing up. Felix the boxer, like Felix the cat, was black, born in St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, and at well over six feet tall he cut a conspicuous figure in Federation-era Sydney. There may be something to this, especially considering that Sullivan was a boxer himself. But there doesn’t seem to be any corroborating data apart from Maegraith’s anecdote.

In recent years some Australian writers have sought to minimise Otto Messmer’s contribution to the origin of Felix, giving the lion’s share of the credit to Sullivan himself. I find most of their arguments circumstantial, if not specious; but even if they were convincing, they could never fully rehabilitate a reputation tarnished by a rape conviction, not to mention that incident in Adolph Zukor’s office.

I’m starting to write articles just to read your comments, Paul.

Thanks, Bob, but whatever your motivations, just keep writing them!

I wonder what Otto Messmer thought of the 1959 Joe Oriolo version of Felix, which has Baby Boomer nostalgia appeal but little else. Except for the missed royalties, he might have thought, Better Sullivan’s name on that than mine.

Well, then…

I’ll now add Pat Sullivan’s name to my list of Most Punchable Faces.

Even if it does look like he would punch back.

These New York articles are astounding, Bob!

Is there any independent confirmation for Eugster, Zamora and Cannata as, erm, responsibles for the Buried Treasure flick?

“Eveready Harton in Buried Treasure” is discussed in FORBIDDEN ANIMATION (1997) by Karl F. Cohen. The account of the dinner for Winsor McCay comes from a 1977 MINDROT interview with Ward Kimball, who was not present at the event but heard about it secondhand. At a screening of the cartoon in San Francisco in the late 1970s, the program notes identified the animators responsible as George Stallings, George Cannata (misspelled “Canata”), Rudy Zamora, and Walter Lantz. Cohen hypothesises that those names were provided by Zamora’s son, Rudy Jr., who was living in San Francisco at the time.

I’ve always thought that the title character’s name may have been inspired by Ernest Everhard, a character in Jack London’s dystopian political novel THE IRON HEEL (1908). It’s certainly the sort of name that schoolboys would have giggled about.

What’s missing in this otherwise fine article is the real secret of Otto Messmer’s Felix: EMPATHY.

Otto discovered little looks at the audience, shoulder shrugs, winks, nods of the head and of course the famous pacing back and forth that revealed that Felix was THINKING. This was long before Pluto was given credit as the first animated cartoon character to register thought on the screen (Playful Pluto). Felix was often in sympathetic situations, homeless and hungry, then adopted by kind and not so kind humans. Audiences really cared about Felix because Otto and company were skilled at not only action, but faces. Felix crossed over the proscenium arch in the theater and his personality had reality to it. This is a landmark accomplishment, even greater than McCay’s. Gertie had personality, but Felix had it in spades and developed.

Well said!

The map here puzzles me.

Wasn’t the little Terry office located in a building at 138 W. 42nd Street (between Sixth and Seventh Avenues) in the ‘teens?

The New Amsterdam Theatre, pictured on the map as being between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, has been at 214 W. 42nd Street (between Seventh and Eighth Avenues) — since its opening in 1903. I’m not sure the New Amsterdam building ever housed Terry’s fledgling operation.

A theatre — the Cameo — was indeed later built at the 138 W. 42nd St. address in 1921, but Terry’s operation may have moved on by then.

You may well be right. I can’t find info on the Cameo theater,

Some background on the Cameo is here:

http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/6499

[It’s often listed as the “Bryant,” as the house was re-named in the early 1940s.]

Terry was at 138 W. 42nd in 1916. Nothing to do with New Amsterdam theater. Terry’s local may be part of Bush Terminal Bldg.

Thanks for the catch.

A correction to the map – and the text – has been made in the post above.

I seem to recall that Van Beuren made a couple of Felix the Cat cartoons. How did they acquire the rights? Were any of the old Sullivan animators working at Van Beuren at the time?

Burt Gillett ran Van Beuren’s stidio. We’ll get there soon.

The story of Felix the Cat is probably one of the most tragic of the theatrical era of animation, and a lot of that can be boiled down to Pat Sullivan, who could easily be described as the John K. of the silent era (up to and including statutory rape, sadly). In addition to his general insanity, his unwillingness to get with the times sunk the once-mighty Felix empire. He stuck his head in the sand regarding the incoming arrival of sound, and when he finally relented, he just slapped sound on in the sloppiest, most haphazard way possible. The animators deserved better, especially Otto Messmer, who created the character in the first place. At least we get the consolation that after Joe Oriolo bought the character to make the TV cartoons that brought him back into the limelight, he made sure to give Messmer the credit he deserved for creating Felix, something Messmer actually lived to see.

Great piece of research, Mr. Coar!

I seem to recall that there was along interview with Otto Messmer in an issue of THE CLASSIC FILM COLLECTOR, but I can’t seem to find it! Anybody know or verify what I’m talking about?