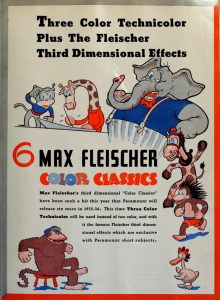

One suspects that what was going to attract the exhibitors to the new series of Color Classics was the improved palette, now that the exclusive hold on the 3-strip Technicolor process had been broken, and others were able to utilize its choice hues. (Not that anyone would notice today from the condition of many of the PD prints circulating, which have seen far better days.) But, as for the exhibitors of the day, it seems that the overall quality of the cartoon could be ignored, provided it had a rich color spectrum.

One suspects that what was going to attract the exhibitors to the new series of Color Classics was the improved palette, now that the exclusive hold on the 3-strip Technicolor process had been broken, and others were able to utilize its choice hues. (Not that anyone would notice today from the condition of many of the PD prints circulating, which have seen far better days.) But, as for the exhibitors of the day, it seems that the overall quality of the cartoon could be ignored, provided it had a rich color spectrum.

Unlike the Screen Songs, the Color Classics tended to favor original songs rather than current pops of the day. Some of these originals were engaging, and linger in the memory.

Somewhere in Dreamland (1/17/36) – A couple of waifs are dragging a wagon along the snowy streets of town, collecting stray bits of wood. On the way, they stop by the window of a shop, which features an array of choice goodies they can’t afford. The kids get their wood home for Mama to cook dinner, which doesn’t amount to a whole lot. Hard bread is featured on the menu. When the little boy complains he’s still hungry, his mother breaks down in tears. The kids go to bed, and try to sleep under moth-eaten blankets. In their dreams, the kids travel to a fantasy land of plenty, with loads of popcorn, ice cream cones, toys, and even new wardrobes growing on “clothes trees”. When the kids wake up and go down to the kitchen, they find a lavish spread which has been provided by the charitable merchants of the town, and have to pinch themselves to make sure they’re not still dreaming! Songs include “Serenade” by Franz Schubert, “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean”, “Baby’s Birthday Party”, and the original title song, by Sammy Timberg and Bob Rothberg.

The Little Stranger (5/1/36) – A variation on “The Ugly Duckling”. A weeping mother hen deposits one of her eggs in a duck’s nest. When the drake takes his hatchlings out to learn all the things a duck does, he finds that one of them – a baby chick – can’t swim. Not realizing the species difference, Drake bawls out the chick, and tells him to go home. The chick is disconsolate When a hawk comes along and tries to nab one of the ducklings, the chick turns into a hero, getting the hawk re-routed into an old mill. The hawk winds up trapped in a wagon wheel, getting the razz from his own young-uns. Drake is quite appreciative of the rescue, and he and the ducks all crow in salute to the baby rooster. Song: – only an original title song, heard over the opening credits.

The Cobweb Hotel (5/15/36) – Two honeymooning flies check in at the Cobweb Hotel – an establishment set in an old roller-top desk, presided over by a spider who just “loves” his clientele. Several other flies have checked in, but have not been able to check out, caught in the web placed in the letter cubicles of the old desk. When the new bridegroom gets an idea of what the spider has in mind, he breaks out, and releases several of the other hotel patrons. They gang up to give the spider the works with pen points, pencil sharpeners, aspirin bottles, and a vat of sticky paste as a final trap. The film ends with the happy couple leaving atop a “litter” consisting of a wedding ring box, with the flies singing their own modification of the lyrics to the title song – “Keep away from the cobweb hotel”. Only one song, the title number, is performed, in full verses by the Spider – a memorable ditty composed by Timberg and Rothberg.

The Cobweb Hotel (5/15/36) – Two honeymooning flies check in at the Cobweb Hotel – an establishment set in an old roller-top desk, presided over by a spider who just “loves” his clientele. Several other flies have checked in, but have not been able to check out, caught in the web placed in the letter cubicles of the old desk. When the new bridegroom gets an idea of what the spider has in mind, he breaks out, and releases several of the other hotel patrons. They gang up to give the spider the works with pen points, pencil sharpeners, aspirin bottles, and a vat of sticky paste as a final trap. The film ends with the happy couple leaving atop a “litter” consisting of a wedding ring box, with the flies singing their own modification of the lyrics to the title song – “Keep away from the cobweb hotel”. Only one song, the title number, is performed, in full verses by the Spider – a memorable ditty composed by Timberg and Rothberg.

Greedy Humpty Dumpty (7/10/36) – A curios entwining of the tale of Humpty Dumpty’s wall with elements of “King Midas”, casting Humpty as a gold-loving monarch who heavily levies tribute from his fairy=tale subjects in the form of gold. A ray of golden sunshine penetrates his golden treasury, and, squinting at the sun, he envisions it as a jewel-encrusted golden disc. He vows to make the sun part of his collection of wealth, and whips his subjects into building the wall of his palace higher and higher, until it literally reaches the surface of the sun (without burning or melting anything!) However, when he breaks through the sun’s surface with a pick, lightning and torrent emerge, first in humanized form to administer a spanking to the monarch, them in bolts that shatter the towering wall, leaving Humpty to suffer the fall of falls back to Earth. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men do reassemble Humpty – but the weight of putting on his crown reduces him again to a pile of eggshell remnants. Again, only one original song provides the underscore, which I assume is titled, “Look Out! Look Out!”, providing a warning to Dumpty of the fall he will ultimately take, and the fate that befalls all “greedy guys.” One of the best of the Color Classics, for its mechanical inventiveness in the wall-constructing sequence, which is in pure Fleischer style.

Hawaiian Birds (8/28/36) – A bird couple is about to enjoy their honeymoon and idyllic life in Hawaii. This gives the Fleischers ample chance to really show off the superiority of the three-strip Technicolor process, and, thankfully, this title is currently among the best preserved in circulating prints. A group of migrating birds from the big city (i.e. New York), whose traveling briefcase seems to identify them as a band, attracts the she-bird, who flies off with them, leaving the male bird disconsolate. He decides to follow to New York to retrieve her, and when he arrives there, finds snow on all the ledges. Meanwhile, his sweetheart is kicked out by the flock as a a no-talent, into the snow. She attempts to commit suicide by jumping off a building with her wings tied – but fortunately lands on her boyfriend, and all is forgiven, as they wing their way back home. Songs: “Aloha Oe”, and “Beneath Hawaiian Skies”, another original by Sammy Timberg.

Play Safe (10/16/36) – A little boy is fascinated by trains. Of course, there were a lot more trains in those days for boys to be fascinated by. He spends most of his day laying across his model railroad track, rising only to let his toy locomotive pass under him, and reading books on more trains all the while. There is, however, a real train track behind his house. Much like a “Buttons and Mindy” episode of Animaniacs, his trusty dog attempts to keep him away from the real locomotives, but the boy escapes anyway, leaving the dog leashed to a tree. The child climbs aboard the rear of a box car as the train starts up, but falls off, hitting his head against the tracks. He lapses into a dream sequence in a giant railroad yard, and mounts a locomotive, setting it in motion at full speed down the track. Another locomotive approaches in the opposite direction, and the two trains, developing faces, attempt to whistle each other to clear the tracks. But neither budges, until they are face to face, rearing up as if a pair of cats ready to do battle. The scene dissolves back to reality, as another locomotive approaches the boy asleep on the tracks. The dog breaks his leash, and, in part by being bumped by the oncoming locomotive, rescues the boy in a burst of speed. Songs include the perennial “Casey Jones”, most popularly recorded by Billy Murray and the American Quartette on Victor and Edison, and by Collins and Harlan on Columbia (later remade for the same label by Irving and Jack Kaufman). Blanche Calloway would adapt it as “Casey Jones’ Special” on Victor in an up-tempo arrangement (below). Charlie Trout and his Melody Artists included it in the 1920’s as part of a four-song piece called, “Transportation Blues”. It would receive many parodies, including “J.C. Holmes Blues” by Bessie Smith on Columbia, and Allan Sherman’s “J. C. Cohen” on one of his comedy albums for Warner Brothers records in the 1960’s. An original title number, written by Tot Seymour and Vee Lawnhurst, takes up the body of the score.

Christmas Comes But Once a Year (12/4/36) – This film has been the subject of a recent post on the “Thunderbean Thursday” column of this website, where a full Technicolor print has finally been located, which is a feast to the eye. It is the classic Christmas story that gave Grampy from the Betty Boop series his only appearance in full color, and allowed the mad genius inventor full rein to create with the bric-a-brac from an orphanage’s kitchen and supply pantries, to brighten Christmas for the waifs of the orphanage when all their cheap toys break down from shoddy workmanship. Grampy not only builds marvelous creations from vacuums and hi-chairs, trains from teapots and cups and saucers, and the like, but transforms umbrellas and a gramophone into a rotating Christmas tree, and himself into Santa Claus with additions from old stovepipes and other assorted items. Songs: “The First Noel”, and the catchy title song, with both music and lyrics by Sammy Timberg. Timberg would find opportunity to reuse his tune in a subsequent season, merely substituting a different holiday to accompany “New Years’”. for Popeye’s “Let’s Celebrake”.

Bunny-Mooning (2/12/37) – Jack and Jill Bunny plan to get married, after he gives ger a “I carrot” ring”. A “leaf” serves as the invitation sent to the wedding guests. The ceremony proceeds in idyllic fashion, with no hint of villainy going on. Three weeks after the release date of this film, it played at the Paramount Theater in New York, on the bill with the feature, “Maid of Salem”, with live appearance by Benny Goodman and his Orchestra between films. This was the performance that launched and cemented Benny’s reputation as the King of Swing. “Love in Bloom” is clucked during the wedding ceremony by a hen. The “Wedding March” is also featured briefly. But the central attraction is a new number entitled “Headin’ for a Weddin” (not to be confused with another song of the same title recorded by Ozzie Nelson in 1933), with music and lyrics both contributed by Sammy Timberg.

Next Time: Betty Boop 1935-36.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

These songs from the Color Classics are all clever, catchy and well-written. Some of them are too inseparable from the cartoons that feature them to stand on their own, but “Somewhere in Dreamland” is a lovely little lullaby that deserved to become a standard.

The song “The Cobweb Hotel” reminded me very strongly of the 1890s waltz “My Sweetheart’s the Man in the Moon” (Jane Russell sings it in “Montana Belle”), to the point where I wondered if Timberg might have been inspired by it. But then it occurred to me that the lyrical scheme of both songs is in the form of a limerick, so they’re bound to be fairly similar on that basis alone.

There’s a second recurring melody in that cartoon, a little foxtrot based on Mendelssohn’s Wedding March. It serves as a leitmotif for newlyweds I. Fly and wife, accompanying them as they arrive at the Cobweb Hotel, play on the telephone dial and ink blotter, etc.

The version of “Casey Jones” that remains first and foremost in my mind is the one used in the Good & Plenty commercials in the 1960s: “Once upon a time there was an engineer! Choo-Choo Charlie was his name, we hear! He had an engine, and he sure had fun! He had Good and Plenty candy to make his train run!”

Somewhat incongruously, “Hawaiian Birds” incorporates a song that was written for another Fleischer cartoon: “I Want a Clean Shaven Man”, sung by Olive Oyl in a Popeye cartoon released earlier in 1936. It plays while the male bird is building his house, and again just before the female bird attempts suicide. It doesn’t really make any sense in this context, but that’s definitely the song. I’d know it anywhere. Years ago I had a girlfriend who used to sing it to me whenever I tried to grow a moustache.

Funny, I always assumed the “Big City Orioles” in “Hawaiian Birds” were from Baltimore, not New York….

“The Cobweb Hotel” is a personal favorite. It’s actually the bride, not the groom, who breaks free from the bed of webs and frees the other victims; in how many other cartoons of the era does the girl save the boy?

“Play Safe” got a lot of play in NYC in my childhood days (1950s-60s) on WPIX, channel 11. It remains fondly remembered by this 70-year-old. Of course, “Christmas Comes But Once a Year” was also frequently seen and remembered.

I remember watching “Play Safe ” on Channel 11 too. But when it was finally released on home video I had forgot its title. I was pleasantly surprised when it turned up as an extra cartoon on a DVD of Fleischer cartoons I eventually purchased.

It’s hard to imagine a more innocuous, inoffensive cartoon than “Bunny Mooning”, yet it appears to have been subjected to heavy-handed butchering by the Production Code Administration. There is an obvious, drastic cut in the middle of the cartoon: the rabbit couple are skipping along merrily to their wedding, and then suddenly the wedding guests are seating themselves in the pews. The correspondingly abrupt cut in the music indicates that the footage was excised after the cartoon had been completed. I think it’s logical to assume that the missing scene showed the exterior of the wedding venue, presumably a church, with the guests filing in. (Earlier in the cartoon, the invitations state that the wedding will take place “in the woods”, but the interior of the venue is laid out like the nave of a church, with rows of pews facing the chancel.)

So what could have been the problem? Well, probably the most strictly enforced aspect of the Production Code was the prohibition on showing any disrespect to religion. If the missing scene from “Bunny Mooning” had a church in it, then there must have been something about it that the censors didn’t like. Maybe there was a funny advertising sign posted on it, like the one on the back of the parson-peacock’s tail at the end of the cartoon. Or maybe there was a sign identifying the place as, say, “St. Bunnyface Church”; there was a St. Boniface Church in midtown Manhattan, not far from the Fleischer studio. Yet even such a mild, harmless little pun as this would have violated the Code for mocking the name of a venerated religious figure.

Whatever the reason, the censorship of “Bunny Mooning” shows how stultifying the creative atmosphere at Fleischer had become. By early 1937, the studio had been complying with the strictures of the Code in every particular for two and a half years, at Paramount’s insistence. Yet they still managed to run afoul of it — and with a twee, saccharine Myron Waldman cartoon like “Bunny Mooning”, of all things.

Joseph Breen, a devout Roman Catholic journalist with ties to the church’s Legion of Decency, was the head of the Production Code Administration for 20 years. When he retired in 1954, believe it or not, he was given an honorary Academy Award for his contributions to the motion picture industry. A good hard kick in the groin would have been more like what he deserved.

The cut in Bunny Mooning exhibits a large visible splice line, blurring, and frame movement that appear characteristic of an edit to the 16mm U.M.&.M./N.T.A. pre-print elements rather than a Production Code-related edit to the original 35mm elements.

I’ll take your word for that, although the disruption to the music suggests that it must have been a splice of fairly substantial proportions.

That’s Andy Kirk’s Orchestra accompanying Blanche Calloway on “Casey Jones”. His band first recorded that arrangement for Brunswick in 1929. Both versions featuring great solos by pianist Mary Lou Williams!

If any film star actually DESERVED Technicolor, it’s Grampy.

I have to saw “Greedy Humpty Dumpty” freaked me out as a kid when King Humpty breaks opens the sun and suffers the consequences (Daffy: “Consequencs, smansequences, as long as I’m rich”).

I agree with Charles Solomon that Fleischer’s use of Technicolor yielded an “acid palette” (even in the Popeye two-reelers) not nearly as effective as the gray scale of the black and white cartoons. But it’s also true that the songs are usually the best part of the otherwise disappointing Color Classics. Occasionally I’ve suggested to friends who sing in clubs and bars to do a set of Fleischer tunes (“Sweet Betty,” “Poor Cinderella,” “Brotherly Love,” “What Can I Do For You,” the Oscar-nominated “Faithful Forever,” “Couple in the Castle,” to name only a few) interspersed with wry commentary: ending “Christmas Comes But Once a Year” by declaring immediately afterward “It took three men to write that.”

Bad character design is only one of the cartoons’ minuses. The mother in “Somewhere in Dreamland” is clearly Olive Oyl after a botched face job (her mouth doesn’t even work when she says “Supper’s ready”) and a modified hairstyle. But Popeye certainly couldn’t be those kids’ father, could he? And those identical orphans Grampy entertains for one day are going to have a rough clean-up job the day after Christmas. God help them when they get hungry after he’s made all the kitchen equipment into makeshift toys.

Ugh, I didn’t think the designs were that bad. Plus, I thought the cartoon highlighted here were quite good espically “Chirstmas Comes But Once a Year”.

Murray Mencher and Charles Newman get screen credit for “Somewhere in Dreamland…

Greedy Humpty Dumpty has long been one of my favorites. I always thought it mixed more with the legend of the Tower of Babel than with King Midas.

Don’t be in a hurry to say audiences did not like the color in the pre-Technicolor Color Classics. I certainly did not like Cinecolor when I first saw cartoons using that process. At the time I was programming four hour animation marathons to large audiences in Toronto, across Canada and in The United States. One thing that surprised me was how much people (and I mean lots of them) absolutely loved the look of those films. It is said that the audience is the only teacher. I have to agree. I learned a lot from and continue to learn a lot from my audiences. I now absolutely love the look of those pre-Technicolor cartoons.

I remember seeing most of these shorts as a child, especially Christmas Comes But Once a Year and The Little Stranger. I came across Greedy Humpty Dumpty for the first time a while back while watching a snippet of it on Classic Arts Showcase. (Since the channel’s mission is to spark the viewer’s interest in the arts by playing short samples, be it opera, ballet, documentaries, animation, etc., it’s quite noticeable the song at the start is left out).