When writing my dissertation and then The Colored Cartoon, I decided not to look at any American animated short films released after 1954. I thought that the year was a good stopping point for African American images because of the decline in appearances of African American caricature after that year and because of the symbolism of 1954 as the year of Brown v. Board. However, that chronological cutoff meant the missed opportunity to discuss Warner Brothers’ “Merrie Melodie” episode The Mouse That Jack Built (1959) in the context of the other films I studied. With 2019 as the 60th anniversary of the release of that film, I thought I’d discuss it now.

“Rochester”

Benny’s driver Rochester also appears as a mouse. But he also appears without pronounced lips, and he does not speak in blackface-inspired dialect. Those distinctions set his appearance in this film apart from his caricatures in any film preceding this one. Ever since Eddie “Rochester” Anderson first appeared on Benny’s program in the 1930s, cartoons applied approximations of his raspy voice to blackface characters, African American servants, a cannibal, and a black crow. Although the crow (Famous Studios’ Buzzy) is the protagonist of his films, he still speaks in the dialect. In contrast, Rochester’s lines of dialogue in The Mouse That Jack Built are grammatically correct sentences.

Here is an excerpt from the cartoon:

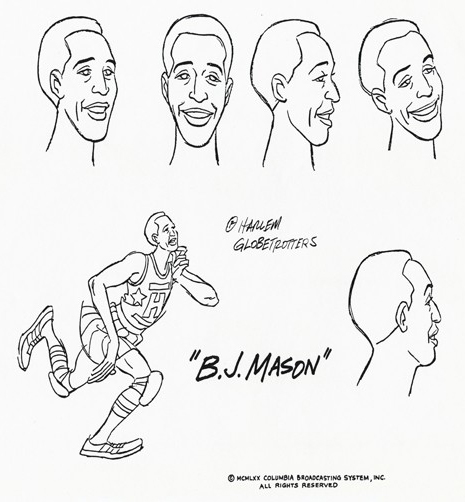

Unfortunately, by 1959, the cartoon short industry was very risk-averse and did not pursue further African American characters devoid of crude ethnic imaging. Instead studios avoided African American caricature in order to avoid losing money if distributors had to withdraw ethnic films that drew too much protest. The next time commercial US animation caricatured famous African Americans was in the television series The Harlem Globetrotters in 1970, and, ironically, Rochester voiced one of the players.

Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson’s character – his final performances – was voicing B.J. Mason on Hamnna Barbera’s “The Harlem Globetrotters”

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

I’ve long been an admirer of Jack Benny: a non-smoker who was never without a cigar, a talented violinist who always played badly, a generous man who became the world’s most famous miser, and a comedian who was funniest when he said nothing at all.

Eddie “Rochester” Anderson’s tenure with the Jack Benny Program was likewise contradictory. He played a domestic servant who, at least in the early days, embodied some of the worst stereotypes associated with the role: laziness, gambling and drinking. Yet he was an immensely appealing and resourceful comic character who regularly got the best of his boss. In real life he was the highest-paid African-American entertainer for many years, as well as one of the country’s wealthiest African-Americans with successful ventures outside of show business.

Years ago, when I saw the 1945 film “Brewster’s Millions”, in which Anderson also plays a domestic servant, several scenes gave me pause. After Brewster promises his friends one by one that he will use his newfound fortune to make all their wildest dreams come true, he finally turns to Anderson and says: “Jackson, you have a job for life” — as though job security were the best one in his position could hope for. Later, when Brewster offers a lavish cash prize for the winner of the poultry contest at the county fair, Anderson excitedly declares: “Poultry? Now you’re talkin’!” I remember thinking that such crude and demeaning jokes would never have flown on the Jack Benny program. So I was surprised to learn that “Brewster’s Millions” was banned in parts of the South because Anderson was shown to be on excessively familiar terms with the white characters.

When his show went on tour, Benny refused to stay at any hotel that would not allow Anderson as a guest; likewise I cannot imagine him accepting any unflattering caricatures of Anderson in “The Mouse That Jack Built”. It might have served as a model for depicting African Americans in cartoons. As it happened, however, another fifteen years would have to pass before Hanna-Barbera produced “Hong Kong Phooey”, starring a funny animal character voiced by an African American actor (Scatman Crothers), who worked as a janitor yet made for an appealing comic hero.

‘Who’s this guy Isaac Stern?” I met Isaac Stern in 1976, and he was quite surprised when I told him how much I enjoyed his appearances on the Jack Benny program. “That was before you were born!” he said, and I made some comment about great art outlasting its creator. Stern then told some very funny anecdotes about his long and warm friendship with the comedian. The first line in “The Mouse That Jack Built” always brings a smile to my face as it brings back fond memories.

He wasn’t a non-smoker.

I’ve always thought it cruel that Eddie Anderson was the only cast member of THE MOUSE THAT JACK BUILT not to be named in the credits. (“Rochester- Rochester”). The February 1958 issue of Warner Club News treats him the same way in an article about the cartoon’s production.

He was sometimes billed that way in live-action movies as well. “Eddie Anderson” may not have meant much to many moviegoers, but everybody knew “Rochester.” In later years, of course, he doubled up and was billed as “Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson.”

I think it might have been Benny’s writer John Tackaberry, in his book on Benny’s radio and TV shows, who pointed out the evolution of the “Rochester” character. In the early years of the character, there were numerous references to things like crap shooting and the like — “typical” (note sarcasto-quotes) of African-Americans. (You see a hint of this in 1946’s “The Mouse-Merized Cat,” where a “Rochester” caricature shows up, and there’s allusions to gambling.) However, by the end of the radio series in the early 50s, and by the time of the television series in the 50s and 60s, these elements had been dropped from Anderson’s character. There was an anecdote I recall (I think from Tackaberry’s book) where an old episode of the radio show was broadcast (presumably while the show was still on NBC), one that included “Rochester” gambling, and merry hell got raised by various parties. In any event, by the time “The Mouse That Jack Built” was made in the mid-1950s, the character of “Rochester” had changed, and the cartoon reflects the much softer-edged version of the character as it existed by then.

Interestingly, another cartoon from Warner Bros, 1946’s “Bacall to Arms”, featured a more stereotypical version of Rochester as the closing “dust/black face” gag.

The cross-pollination between Benny, his show and the Warner Bros. cartoon department likely also didn’t hurt as far as the designs went — besides Mel, Bea and the other voice actors, even Carl Stalling did the music for the climactic scene in “The Horn Blows At Midnight” — though by the time you get to the late 1950s, none of the worst of the African-American charactures were around in the new cartoons (Paramount released “Chew Chew Baby” a year before Warners’ did this cartoon, but while the subject was a cannibal loose in Cincinnati, the color selections avoided any direct inference to the old African cannibal stereotype, but not enough to keep the ban hammer from coming down in most of the major metro markets when the cartoons went into syndication).

Just about every source says Rochester played Bobby Jo in the Globetrotters cartoon, but I never hear his voice. There is an Eddie Anderson listed in the credits, but I suppose he easily could be a different Eddie Anderson. Or it’s possible Rochester voiced a one off character. Anyone able to shed further light on this?

Did you know why Anderson had that raspy voice to begin with?

He lost it at a young age from having a job as a paper boy, and was constantly shouting.

I recall a very late Jack Benny special. In one bit Anderson was driving a Rolls Royce with Benny beside him, trading gags. At the end Benny got out of the Rolls, thanked Anderson for the ride and added, “By the way — nice car you’ve got here.”

I believe when Eddie Anderson appeared as the What’s My Line Mystery Guest he signed in as “Rochester” and was referred to as such by both the panel and John Daily.